CRISPR CRITTERS

Nobel Prize in chemistry awarded for 'genetic scissors' discoveryChemical scientists Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna have been awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their research into genome editing and the discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 "genetic scissors."

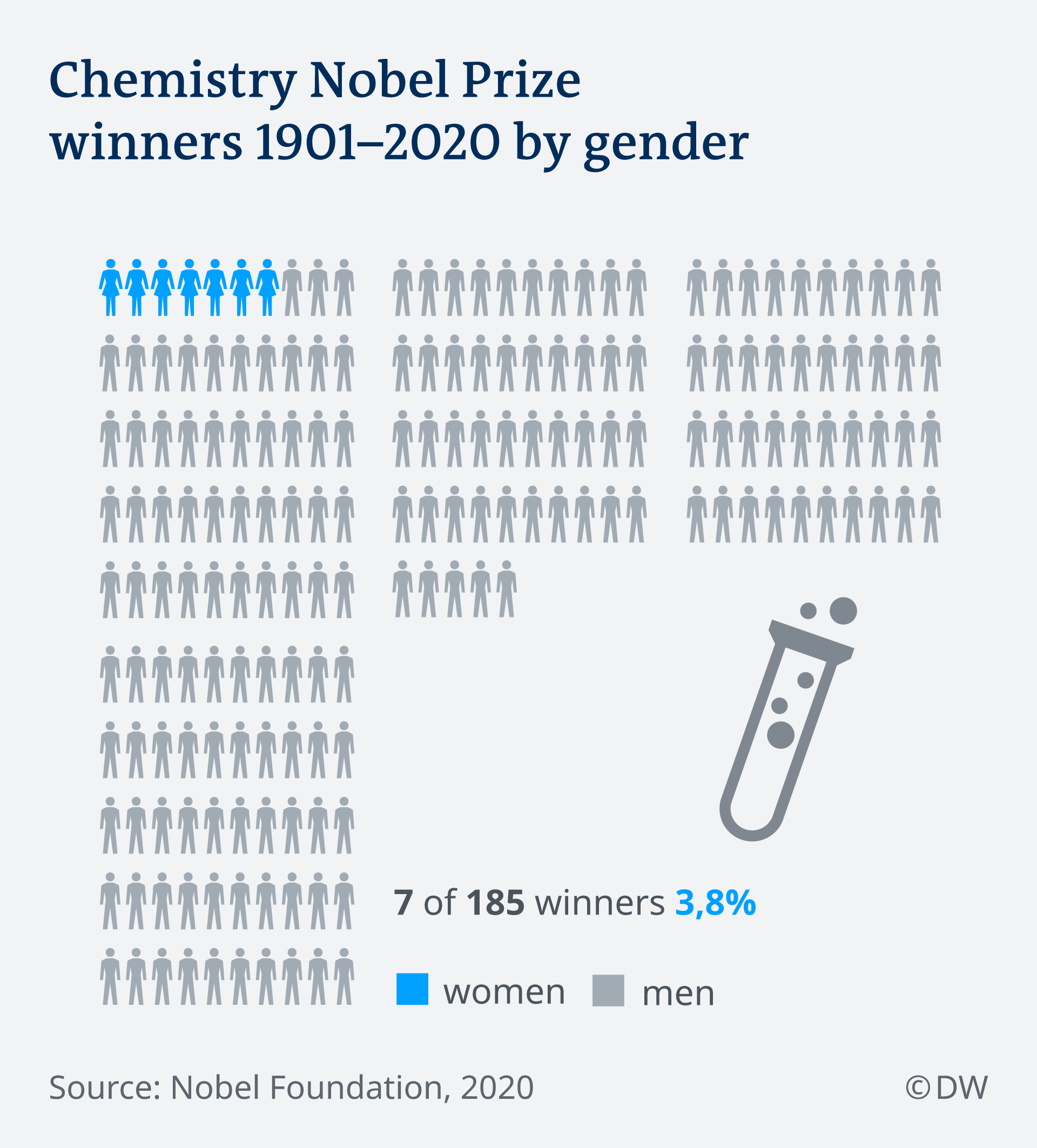

Chemical scientists Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry on Wednesday, becoming only the sixth and seventh women ever to win the award in over a century.

The pair's research concerned "the development of a method for genome editing." Charpentier of France currently works in Germany and Doudna, an American, discovered the CRISPR-Cas9 "genetic scissors" in 2012, a breakthrough that "has taken the life sciences into a new epoch," the Nobel Committee said.

"This year's prize is about rewriting the code of life," the committee said. The tool the scientists developed can be used to change the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms with extremely high precision.

Charpentier is head of the Max Planck Insitute for the Science of Pathogens in Germany. Doudna is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Read more: Will 'Prime Editing' make genetic scissors more precise?

Only seven women have won the prize, including Marie Curie

Rewriting the code of life

CRISPR is a molecular tool that allows scientists to make extremely precise changes to the genetic code of organisms that are still alive. It stands for "clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats," patterns in DNA discovered already in 1987, but which remained mysterious for years until evidence emerged in the mid-2000s that they belonged to the antivirus defense system of bacteria. What was happening was the bacteria were taking sections of the DNA of viruses and building them into their own genome.

The enzyme used by the bacteria has the codename Cas, and this is where the key breakthrough came. In 2012, teams in the US and Europe led by Doudna and Charpentier showed how the Cas system could be turned into a universal 'cut and paste' tool for editing gene sequences.

Read more: ECJ judgment: Is CRISPR-Cas9 "genetic engineering" at all

Practical applications

Lennart Randau, of Philipps University in Marburg, Germany, called CRISPR-Cas9 one of the "most beautiful examples we have of how basic research can revolutionize the entire science world."

Randau heads the prokaryotic RNA department at Philipps University and told DW that we are now "at a point where we can cleave human DNA very specifically and faster than ever before. We can take a gene that causes disease and correct it. This is the great impact of the CRISPR-Cas9 discovery for humanity."

There are companies all over the world testing this technology in clinical trials right now, Randau added, saying that it was "very possible that the method could be used in approved medical procedures within the next two years."

An application of CRISPR is particularly useful in altering the DNA of various plants and animals so they can withstand certain blights or viruses.

Lingering concerns

CRISPR has also been the subject of widespread controversy.

Indirectly addressing the ethical questions brought about by the discovery of genetic scissors, the chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, Claes Gustaffson, warned that the technology must be "used with great care."

A scientist in China was imprisoned in 2019 for creating the world’s first "gene-edited babies." He Jiankui had announced to the world in the fall of 2018 that he had used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to produce human embryos that were immune to HIV. The experiment involved a woman who had already successfully given birth to genetically manipulated twins.

Another concern regarding the technology is what it does to the genetic material being altered. A systematic investigation published in 2018 in the journal Nature Biotechnology documented significant mutations to both mouse and human cells treated with the CRISPR-Cas9 technique.

In some cases, the mutations were so extensive that the researchers concluded that the genetic damage ensuing could lead to potentially serious health risks.

Read more: Genetically edited babies: An ethical transgression

The flurry of attention (and controversy) that ensued in the wake of the CRISPR-Cas9 breakthrough, spanning academic areas from genetics to molecular biology and bioethics, was also overshadowed by a patent conflict.

Another US team beat them to a patent for applying the method on human cells, sparking a legal row over priority - and in February 2017, the US patent office ruled against Doudna and Charpentier. Despite this, they remain widely credited as the real pioneers of CRISPR by fellow scientists.

Asked at Thursday’s ceremony whether the Nobel committee considered including any other scientists in the 2020 prize, chemistry chair Claes Gustafsson said curtly that “this was a question we did not consider.”

The prestigious award comes with a gold medal and prize money of 10 million Swedish krona (about €950,000; $1.1 million).

As it did this year, the award has frequently honored work that led to practical applications in use today, such as last year's win for the brains behind the lithium-ion battery.

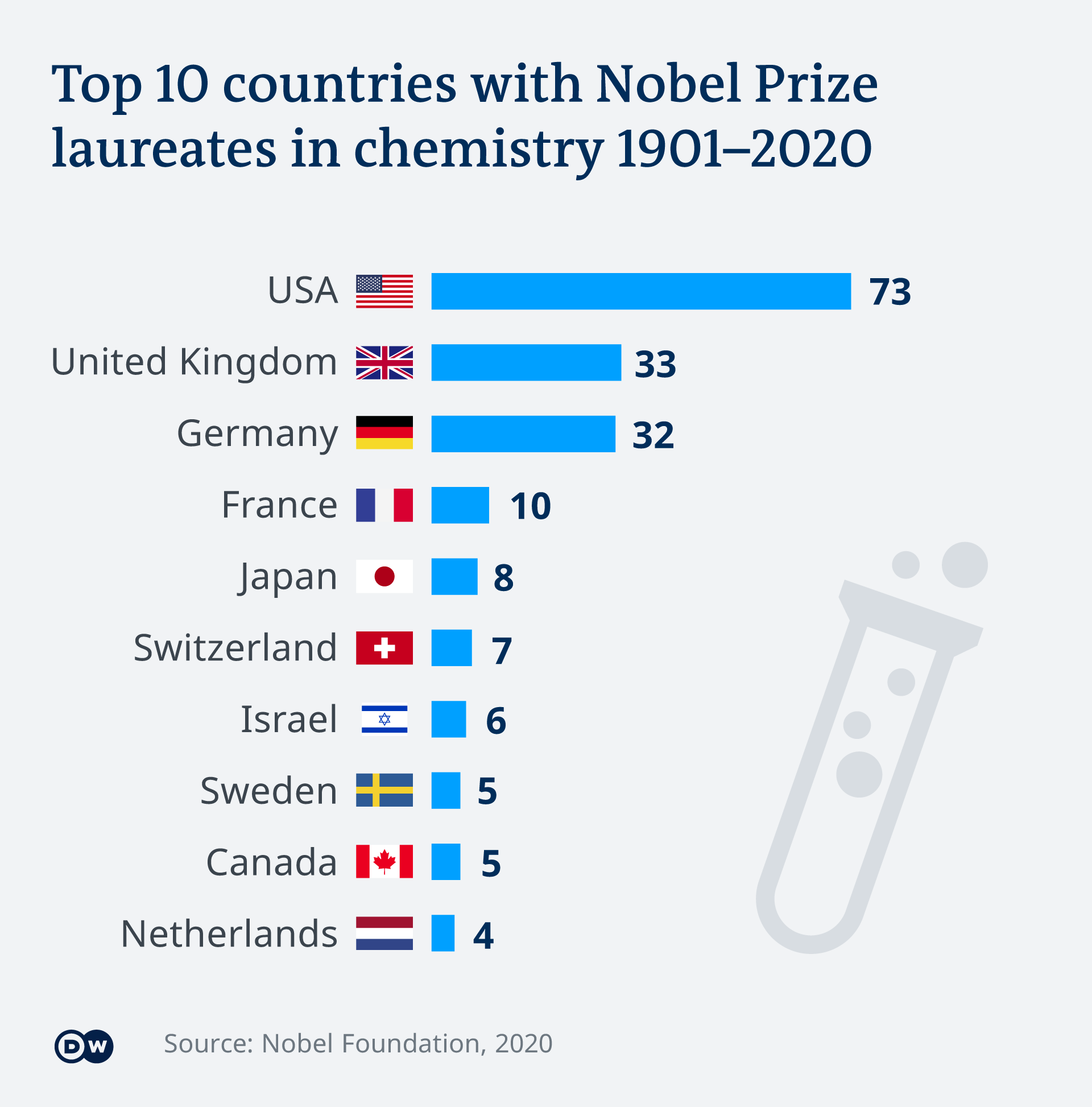

Most winners of the chemistry prize hailed from the US, the UK and Germany

Week of awards

On Monday, the committee awarded its prize for physiology or medicine to US scientists Harvey J. Alter and Charles M. Rice as well as British-born scientist Michael Houghton for discovering the hepatitis C virus. On Tuesday, three astrophysicists shared the award in physics for their research into black holes.

The other prizes awarded by the committee are for literature, peace and economics, most of which will be announced later this week. The winner of the peace prize will be announced on Friday.

The awards, handed out almost every year since 1901, come with a gold medal.

No comments:

Post a Comment