Leaked police data reveals level of violence against protesters in Belarus

Over the past two months, Belarus has witnessed unprecedented violence against protesters in the aftermath of its presidential election. New data confirms its scale.

Media Zona

3 November 2020

Illustration: Maria Tolstova / Mediazona

“Everyone was on their knees, they kept on cramming people into the bus. And then the violence started. The riot police officer said that we had to get up as fast as we could, grab our things and leave the bus. And they started beating people until they stood up. One of them would hold someone while the other beat them. They were just beating and saying: ‘What did you want, bitch, change?’”

This is how one resident of Minsk describes his arrest on 9 August. Alongside thousands of others, journalist Alyaksei Khudanau had gone out to protest against Belarus’ election results after Alyaksandr Lukashenka had been declared the winner.

Official results awarded Lukashenka 80% of the vote, but a significant number of Belarusians believe that the results were falsified, and that Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the only independent candidate, is the real winner of the election. Other candidates were forced to either leave the country or have been arrested, including Tsikhanouskaya’s husband, popular video blogger Siarhei Tsikhanousky.

The protests have not let up since. Every week, tens of thousands of residents of Minsk, the capital, and other cities come out onto the streets to protest against Lukashenka, who has been in power for 26 years. In Minsk, the numbers of attendees have exceeded 100,000 - a huge figure for a city of two million. In response, Belarusian police have used riot batons and water cannons to disperse people. The EU has now sanctioned Belarusian officials for election falsification and police violence.

The police response was particularly brutal immediately after the election. In the days after 9 August, masked police officers detained people across Minsk, shooting flash grenades and rubber bullets at crowds, beating people on city streets, police vans and police stations. Several people died amid the violence: a special forces officer shot protester Alyaksandr Taraikousky dead in Minsk; in Brest, a plain clothes police officer shot Hienadz Shutau, a biker; and Mikita Kryutsou, a football fan, died in unclear circumstances in the city of Maladzyechna (the official version is suicide).

The exact number of people who have suffered at the hands of the Belarusian police is unknown. Belarusian state agencies do not publish statistics on violent incidents involving the police, but as we have discovered - they do collect this information.

Mediazona, a Russian media outlet which focuses on the law and justice system, recently received a data archive held by Belarus’ Investigative Committee from an anonymous source. These documents consist of several spreadsheets containing information about individual instances of police violence, as well as inspections concerning reports of torture. Analysis of these documents shows that the minimum number of people injured by Belarusian police during protests in August and September 2020 is 1,373 people.

Meanwhile, Lukashenka refuses to negotiate with protesters. Instead, in his public remarks, he constantly thanks the Belarusian police. “You have stopped this trash on the clean, comfortable [streets] of Minsk,” Lukashenka said in late September. Indeed, the Belarusian authorities have opened a criminal case into an “attempted coup of state power” by members of the Coordination Council, set up by the Belarusian opposition - of whom many have fled the country or are now under arrest. Ordinary protesters are also facing criminal cases. According to human rights defenders, 435 people are facing prosecution as a result of Belarus’ election campaign and the ensuing protests.

Despite the large number of injuries, the Belarusian authorities have not opened a single investigation into violence committed by police officers.

In cooperation with Mediazona, openDemocracy publishes their investigation in translation here. You can read the full version here.

Akrestsina detention centre in Minsk, one of the main sites of violence against people detained during Belarus' pro-democracy protests | (c) Kommersant Photo Agency/SIPA USA/PA Images. All rights reserved

Why we trust this data presented by an anonymous source

Mediazona was already familiar with one of the documents in the archive - a spreadsheet of injuries inflicted by flash grenades, rubber bullets and tear gas. We had previously received this document from a different anonymous source. Part of the records were accompanied by the names of hospitals in Minsk where injured people were taken. We showed this information to sources in Minsk City Hospital No. 10 and the city’s clinical emergency care hospital. In the latter, our data matched the hospital’s entire list of patients for that time, whereas our source in Hospital No. 10 stated that two of the people in our list did not contact them for medical treatment.

Many of the more serious cases connected to protesters’ eye injuries, amputations, comas and deaths have been described by journalists previously, including by Mediazona. Descriptions of these incidents matched information held in our archive.

We also checked information concerning beatings at Minsk’s Akrestsina jail against prisoner lists compiled by the Viasna human rights centre. The team also showed the documents to a source in one of the Investigative Committee’s central directorates. They confirmed the spreadsheets and other documents were genuine.

How we analysed the severity of the injuries

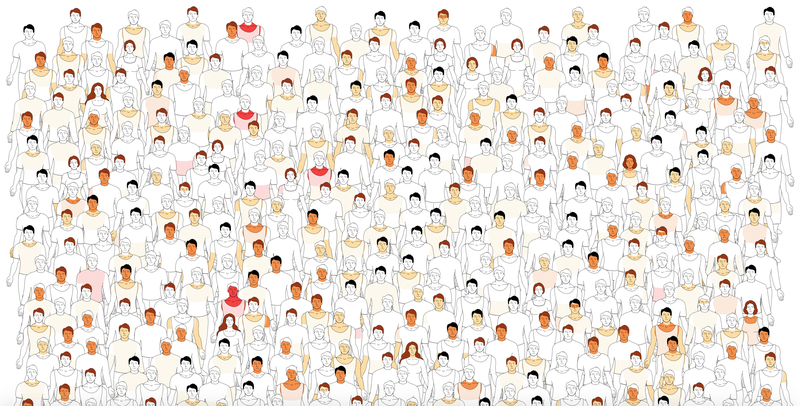

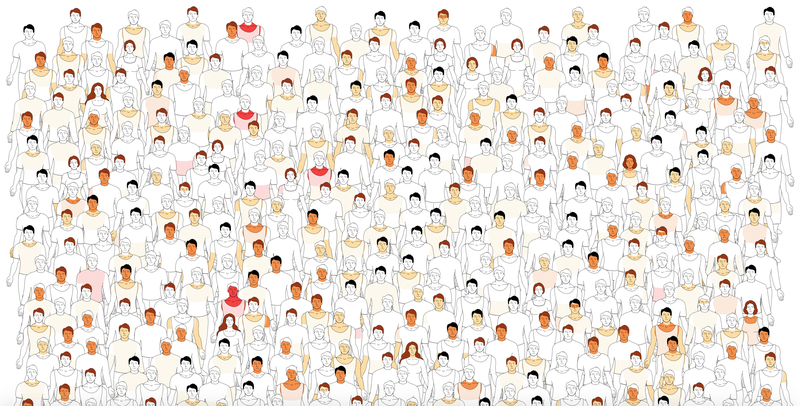

The Investigative Committee’s documents report medical diagnoses given to protesters, and from the majority of diagnoses it is clear how exactly protesters were injured. We have visualised these injuries via silhouettes representing each of the 1,373 people injured.

We categorised injuries by severity - light injuries (1), medium injuries (2) and heavy injuries (3). If part of someone’s body was not injured, we indicated it (0 points). We also analysed injuries in terms of how they were inflicted - beating, rubber bullets, flash grenades or gas.

We categorised bruising, contusions and light burns as light injuries; lacerated wounds, head injuries and multiple traumas - medium; and firearm wounds, internal injuries, broken bones and amputations - heavy.

With the average age of an injured person coming to 31, young men were most likely to be injured at the protests. The worst injuries came from rubber bullets and flash grenades.

Why we trust this data presented by an anonymous source

Mediazona was already familiar with one of the documents in the archive - a spreadsheet of injuries inflicted by flash grenades, rubber bullets and tear gas. We had previously received this document from a different anonymous source. Part of the records were accompanied by the names of hospitals in Minsk where injured people were taken. We showed this information to sources in Minsk City Hospital No. 10 and the city’s clinical emergency care hospital. In the latter, our data matched the hospital’s entire list of patients for that time, whereas our source in Hospital No. 10 stated that two of the people in our list did not contact them for medical treatment.

Many of the more serious cases connected to protesters’ eye injuries, amputations, comas and deaths have been described by journalists previously, including by Mediazona. Descriptions of these incidents matched information held in our archive.

We also checked information concerning beatings at Minsk’s Akrestsina jail against prisoner lists compiled by the Viasna human rights centre. The team also showed the documents to a source in one of the Investigative Committee’s central directorates. They confirmed the spreadsheets and other documents were genuine.

How we analysed the severity of the injuries

The Investigative Committee’s documents report medical diagnoses given to protesters, and from the majority of diagnoses it is clear how exactly protesters were injured. We have visualised these injuries via silhouettes representing each of the 1,373 people injured.

We categorised injuries by severity - light injuries (1), medium injuries (2) and heavy injuries (3). If part of someone’s body was not injured, we indicated it (0 points). We also analysed injuries in terms of how they were inflicted - beating, rubber bullets, flash grenades or gas.

We categorised bruising, contusions and light burns as light injuries; lacerated wounds, head injuries and multiple traumas - medium; and firearm wounds, internal injuries, broken bones and amputations - heavy.

With the average age of an injured person coming to 31, young men were most likely to be injured at the protests. The worst injuries came from rubber bullets and flash grenades.

A selection of protesters coded according to their injuries

| Illustration: Maria Tolstova / Mediazona

Belarusian police aimed for protesters’ vital organs

Judging by injuries caused by rubber bullets (40 cases), it is clear that police officers often shot people in the head, chest and stomach when dispersing protests - and these weapons caused the most serious injuries. On 10 August, 34-year-old Alyaksandr Taraikousky died from a rubber bullet shot to the chest - holding his hands in the air, he had approached special forces officers near the Pushkinskaya metro station in Minsk.

One 24-year-old protester received a rubber bullet to the stomach, leading to a hernia of the small intestine; another participant, a 37-year-old businessman, had his rib cage penetrated by a rubber bullet, causing damage to his right lung. Doctors diagnosed him with open pneumothorax, where air accumulates between the chest wall and lung after an open chest wound - which in serious instances can lead to a collapsed lung.

“I was in a coma for three days, but I was awake for a few moments. The doctors say it’s rare, but it happens,” recalled Alyaksandr Pastukhau, whose lung was penetrated by a rubber bullet. “I remember how they cut my clothes off. The doctors’ speaking when they tried to straighten out my lung during the operation. And how my brain was panicking: it’s sending signals, but my body isn’t responding. And it was terrifying that I could wake up with brain damage. It’s surprising that they shot from such a short distance at my chest. In a way, it’s good they shot me in the right lung. If they’d shot me in the left, we might not be speaking now.”

When police fired rubber bullets at protesters’ heads, they caused head traumas and broke facial bones. For instance, the data shows how a 40-year-old man wound up in hospital with the following diagnosis: “closed head trauma, concussion, multiple gunshot injuries to the right jaw.” His rib cage, stomach and left thigh were also injured. Another protester, 29, was hit by a rubber bullet, which smashed through his maxillary sinus, just behind his cheek, fracturing his nose. Another person was shot with a rubber bullet in the eye, receiving a serious contusion.

Why does the Belarusian Investigative Committee hold data on injured persons and how many people were injured?

It is impossible to give an overall number of people injured at protests in Belarus. The data we received only relates to the situation in Minsk, although police used violence to disperse crowds in other cities. The data in our possession shows instances where law enforcement received information from a hospital or an injured party contacted them to report physical harm.

A source in Minsk City Hospital No.10, which received a large number of injured persons during the protests, explains that doctors contact the police regarding all incidents of physical violence. An emergency service worker in Minsk confirms this procedure: “If we write a diagnosis such as closed head trauma, dislocation, broken bones and so on in our call-out cards, you need to indicate how the injury was caused. We just put down ‘criminals’ and wrote that, according to the patients, the injuries were caused by police officers, riot police and traffic police.” According to this source, this kind of information is automatically passed on to the police, and doctors have to later give statements.

Other protesters may have received injuries that did not require treatment in hospital, or could have contacted volunteer medics for help. Many people injured during the protesters did not contact the Investigative Committee - some may have thought it pointless, others may have feared criminal prosecution. There are cases where an official complaint led to a criminal case against someone injured during the protests - for example, this happened to Anastasia Dudina, whose eardrum was injured after a flash grenade exploded nearby. After leaving hospital, she wrote a complaint to the Investigative Committee, and then became a suspect in a criminal investigation into “mass unrest”.

This situation encourages people to go into hiding, leave the country or not contact Belarusian law enforcement. The 1,373 injuries in our archive are therefore only a minimal estimate of the numbers of injuries. In reality, there are definitely more.

How flash grenades injured protesters

Flash grenades were used en masse during the first days of the protest, and would explode at thigh level or lower when they hit crowds of people, leaving injuries across a person’s whole body - while the grenade’s shock wave led to serious bruising and head traumas.

Indeed, grenades used by Belarusian police caused no less serious injuries than rubber bullets. When a flash grenade exploded near one 30-year-old man, the explosion ripped off his right foot. For two other protesters, flash grenades broke a finger on their left hand, their left foot and their calf bone - shattering these bones into multiple pieces. A flash grenade also fractured a vertebra in a 33-year-old man’s lower back.

For one injured man, a fragment of a flash grenade entered his chest, leading to pneumothorax.

“I live near the Pushkinskaya Metro,” says Heorhiy Saikousky, a Minsk resident who lost a foot to a flash grenade. “On 10 August, I was coming home around 11pm with some friends. I heard some explosions, but I didn’t have internet access on my phone, and I didn’t understand what was going on. Suddenly I saw the police. They were around 100 metres from me. As far as I could tell, the protesters were near the Ice palace [an indoor sporting arena in Minsk], but there was no one really near me. I couldn’t have predicted that a flash grenade would fly into this empty space.”

Most people injured by riot equipment came to hospital straight off the street, avoiding police stations and detention centres. The more seriously injured people were sent to a military hospital, while the rest were divided between city hospitals and Minsk’s emergency hospital.

“We saw a lot of multiple injuries,” an emergency service worker tells us. “These are always closed head traumas and then different combinations: broken ribs, shoulder bones, hip bones, or broken extremities. Bruises, blunt force injuries, scratches - we weren’t coding these, we just described where they were.”

Video showing Belarusian police using flash grenades to disperse protesters in Minsk, on the evening of election day, 9 August

Most people were beaten after being detained by police, not during street clashes

More than half of the injuries took place in police vans, police stations and detention centres in Akrestsina and Zhodzina - that is, when people were not resisting the police, let alone represented a risk. Many were beaten on several occasions - during detention, then in the police van or station, and then in the detention centre. In many cases, this torture went on for several days.

Police specifically beat detainees on the head and buttocks

After being beaten at the Akrestsina detention centre and police stations, detainees were released with head traumas and bruising to their spine, abdomen, shoulders, buttocks and thighs. Around 200 people received head traumas and concussions. Some detainees were placed face-down on the floor or with their faces against the wall, and were then beaten with riot sticks. On 11 October, the NEXTA Telegram channel published a video showing how detainees were forced through a column of police officers, who beat them as they went.

More than 25 people contacted hospitals with broken bones and serious injuries. One young man, 21, was beaten until the main airway in his left lung was ruptured, causing air to escape from his lungs into his chest cavity. Another man the same age received two broken ribs. Indeed, the latter’s whole body was covered in bruises - his chest, back, thighs, knees, shoulders and left hand.

Belarusian police aimed for protesters’ vital organs

Judging by injuries caused by rubber bullets (40 cases), it is clear that police officers often shot people in the head, chest and stomach when dispersing protests - and these weapons caused the most serious injuries. On 10 August, 34-year-old Alyaksandr Taraikousky died from a rubber bullet shot to the chest - holding his hands in the air, he had approached special forces officers near the Pushkinskaya metro station in Minsk.

One 24-year-old protester received a rubber bullet to the stomach, leading to a hernia of the small intestine; another participant, a 37-year-old businessman, had his rib cage penetrated by a rubber bullet, causing damage to his right lung. Doctors diagnosed him with open pneumothorax, where air accumulates between the chest wall and lung after an open chest wound - which in serious instances can lead to a collapsed lung.

“I was in a coma for three days, but I was awake for a few moments. The doctors say it’s rare, but it happens,” recalled Alyaksandr Pastukhau, whose lung was penetrated by a rubber bullet. “I remember how they cut my clothes off. The doctors’ speaking when they tried to straighten out my lung during the operation. And how my brain was panicking: it’s sending signals, but my body isn’t responding. And it was terrifying that I could wake up with brain damage. It’s surprising that they shot from such a short distance at my chest. In a way, it’s good they shot me in the right lung. If they’d shot me in the left, we might not be speaking now.”

When police fired rubber bullets at protesters’ heads, they caused head traumas and broke facial bones. For instance, the data shows how a 40-year-old man wound up in hospital with the following diagnosis: “closed head trauma, concussion, multiple gunshot injuries to the right jaw.” His rib cage, stomach and left thigh were also injured. Another protester, 29, was hit by a rubber bullet, which smashed through his maxillary sinus, just behind his cheek, fracturing his nose. Another person was shot with a rubber bullet in the eye, receiving a serious contusion.

Why does the Belarusian Investigative Committee hold data on injured persons and how many people were injured?

It is impossible to give an overall number of people injured at protests in Belarus. The data we received only relates to the situation in Minsk, although police used violence to disperse crowds in other cities. The data in our possession shows instances where law enforcement received information from a hospital or an injured party contacted them to report physical harm.

A source in Minsk City Hospital No.10, which received a large number of injured persons during the protests, explains that doctors contact the police regarding all incidents of physical violence. An emergency service worker in Minsk confirms this procedure: “If we write a diagnosis such as closed head trauma, dislocation, broken bones and so on in our call-out cards, you need to indicate how the injury was caused. We just put down ‘criminals’ and wrote that, according to the patients, the injuries were caused by police officers, riot police and traffic police.” According to this source, this kind of information is automatically passed on to the police, and doctors have to later give statements.

Other protesters may have received injuries that did not require treatment in hospital, or could have contacted volunteer medics for help. Many people injured during the protesters did not contact the Investigative Committee - some may have thought it pointless, others may have feared criminal prosecution. There are cases where an official complaint led to a criminal case against someone injured during the protests - for example, this happened to Anastasia Dudina, whose eardrum was injured after a flash grenade exploded nearby. After leaving hospital, she wrote a complaint to the Investigative Committee, and then became a suspect in a criminal investigation into “mass unrest”.

This situation encourages people to go into hiding, leave the country or not contact Belarusian law enforcement. The 1,373 injuries in our archive are therefore only a minimal estimate of the numbers of injuries. In reality, there are definitely more.

How flash grenades injured protesters

Flash grenades were used en masse during the first days of the protest, and would explode at thigh level or lower when they hit crowds of people, leaving injuries across a person’s whole body - while the grenade’s shock wave led to serious bruising and head traumas.

Indeed, grenades used by Belarusian police caused no less serious injuries than rubber bullets. When a flash grenade exploded near one 30-year-old man, the explosion ripped off his right foot. For two other protesters, flash grenades broke a finger on their left hand, their left foot and their calf bone - shattering these bones into multiple pieces. A flash grenade also fractured a vertebra in a 33-year-old man’s lower back.

For one injured man, a fragment of a flash grenade entered his chest, leading to pneumothorax.

“I live near the Pushkinskaya Metro,” says Heorhiy Saikousky, a Minsk resident who lost a foot to a flash grenade. “On 10 August, I was coming home around 11pm with some friends. I heard some explosions, but I didn’t have internet access on my phone, and I didn’t understand what was going on. Suddenly I saw the police. They were around 100 metres from me. As far as I could tell, the protesters were near the Ice palace [an indoor sporting arena in Minsk], but there was no one really near me. I couldn’t have predicted that a flash grenade would fly into this empty space.”

Most people injured by riot equipment came to hospital straight off the street, avoiding police stations and detention centres. The more seriously injured people were sent to a military hospital, while the rest were divided between city hospitals and Minsk’s emergency hospital.

“We saw a lot of multiple injuries,” an emergency service worker tells us. “These are always closed head traumas and then different combinations: broken ribs, shoulder bones, hip bones, or broken extremities. Bruises, blunt force injuries, scratches - we weren’t coding these, we just described where they were.”

Video showing Belarusian police using flash grenades to disperse protesters in Minsk, on the evening of election day, 9 August

Most people were beaten after being detained by police, not during street clashes

More than half of the injuries took place in police vans, police stations and detention centres in Akrestsina and Zhodzina - that is, when people were not resisting the police, let alone represented a risk. Many were beaten on several occasions - during detention, then in the police van or station, and then in the detention centre. In many cases, this torture went on for several days.

Police specifically beat detainees on the head and buttocks

After being beaten at the Akrestsina detention centre and police stations, detainees were released with head traumas and bruising to their spine, abdomen, shoulders, buttocks and thighs. Around 200 people received head traumas and concussions. Some detainees were placed face-down on the floor or with their faces against the wall, and were then beaten with riot sticks. On 11 October, the NEXTA Telegram channel published a video showing how detainees were forced through a column of police officers, who beat them as they went.

More than 25 people contacted hospitals with broken bones and serious injuries. One young man, 21, was beaten until the main airway in his left lung was ruptured, causing air to escape from his lungs into his chest cavity. Another man the same age received two broken ribs. Indeed, the latter’s whole body was covered in bruises - his chest, back, thighs, knees, shoulders and left hand.

Injuries connected to sexual violence

Three detainees received injuries consistent with sexual violence either at the Akrestsina detention centre or en route there. A 31-year-old man was hospitalised with intramucosal hemorrhages of the rectum, a 29-year-old man had an anal fissure and bleeding. A third party, a 17-year-old man, received - aside from other injuries - an injury to his rectal mucosa.

Ales, a 30-year-old programmer (whose name has been changed), told journalists how he was raped. “The riot police demanded that I unlock my phone, and then called the senior officer. He started threatening me with inserting a riot stick into my anus. I was lying on the floor of the police van, and he cut my shorts and underwear open. He asked his colleagues for a condom. I was lying on the floor face-down, but I could see how he put the condom on the riot baton. And then he inserted it into my anus. He pulled it out and then asked for the password again. And then he began beating me - punching and kicking. I was hit in the ribs, the face, my teeth - two of them were broken.”

10 August: violence on the street - followed by beatings at Akrestsina detention centre, police stations

In Minsk, police organised the most brutal dispersal of protesters on 10 August. On city streets, not counting beatings in police stations and Akrestsina detention centre, 291 people received injuries. That day also saw mass detentions, with more than 3,000 people arrested. In the days after, law enforcement would beat detainees again and again.

Siarhei (name changed) was detained on 10 August, and recalls how he and other detainees were brought to Akrestsina. “When we were released [from the police van], they didn’t explain the rules - you couldn’t look around, they would just hit you and say: ‘Run!’ You run on, they beat you and say: ‘Get down!’ Then you run on and they hit you: ‘Hands behind your back!’ People didn’t understand where they’d ended up, but first they beat you, then they explain. By that point every one had been beaten - perhaps lightly, but still.”

People were then lined up on their knees along the wall in the Akrestsina detention centre yard.

“We ran out of the van and stood next to the fence on our knees,” Siarhei continues. “On our knees. Those who were beaten in the legs could not physically get on their knees and had to sit down. And then they were beaten with riot batons for that. They beat them until they themselves realised that someone couldn’t get on their knees, or they just dragged them away when someone fell.”

The next eruption of violence came on 13 September during a march on the Belarusian government residential compound in Drazdy just outside Minsk. For the first time in a month, more than two dozen cases of violence were reported in our data - and that’s when our data ends.

Belarusian law enforcement beat everybody, including women and teenagers

Violence by Belarusian security forces was conducted en masse and was not selective: officers did not try to suppress specific groups of people whom they considered a threat, but attempted to beat everybody they found.

Alyaksandr Lukashenka and Belarusian state propaganda insisted that the election rallies were attended mostly by drunks and drug users. “Some people are high, a lot of drunks, people with drugs,” is how Lukashenka described protesters immediately after the election. The data in our possession disproves this claim: the number of people whose diagnoses refer to intoxication is insignificant - less than 2%. There are no references in the medical reports of drug use.

The data refers to at least 24 injured persons under 18. They were beaten exactly the same as adults: under-age persons received concussions, cuts and bruises. One 17-year-old, Timur, was beaten to the extent that he had to be placed in a medically-induced coma.

The data refers to 57 women injured during the protests. The oldest of them is 72: on 12 August, police officers beat her near the investigative detention centre on Minsk’s Volodarsky Street, breaking her wrist. Women were subject to torture following detention, too. Judging by the seriousness of the injuries, it’s clear women were beaten exactly the same as men.

As far as we understand, not a single criminal investigation has been opened into the actions of Belarusian law enforcement during the protests. The Minsk Prosecutor’s Office refused to state whether torture committed in the Akrestsina detention centre is being investigated, stating that information was “for internal use”.

On Sunday 11 October, Belarusian law enforcement once again resorted to brutal detentions and beating protesters. The country’s deputy interior minister stated that the police are ready to use lethal force.

Since then, Belarusian authorities have dispersed Sunday protests in the country forcefully, but people continue to attend them. On 1 November, Minsk witnessed a “March against terror” - participants aimed to visit Kurapaty, a Soviet execution site outside the capital. The authorities, however, responded with force, and have charged more than 200 detainees as part of an investigation into “mass unrest” during the march.

Editor: Dmitry Treshchanin

Text: Maxim Litvarin, Anastasia Boiko, Yegor Skovoroda

Graphics: David Frenkel, Nikita Shulaev

Illustration: Maria Tolstova

Analysis: Yegor Skovoroda, Maxim Litavrin, Anastasia Boiko, David Frenkel, Dmitry Treshchanin, Anastasia Poryseva, Khatima Mutaeva, Viktoria Rozhitsyna, Mikhail Lebedev

Translation: openDemocracy

No comments:

Post a Comment