George Calhoun Contributor

Markets

(FILES) This file photo taken on October 13, 2020 shows the Ant Group headquarters in Hangzhou, in ... [+] AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

The most shocking, financial-market-impacting event this week was… No, not the electoral chaos in the United States (widely expected, priced in, a little turbulence smoothly ridden out).

It was the news that the Chinese government decided they had to step on an ant… specifically, on Ant – that is, the Ant Group (formerly known as Ant Financial Services). Days before Ant’s huge scheduled public offering in Shanghai and Hong Kong, Chinese regulators (acting probably at the direction of Xi Jinping himself) summoned the company’s founder Jack Ma (China’s richest man, by the way) to Beijing for a bit of re-education.

As the Chinese press put it, “regulatory interviews” were conducted.

“The regulators provided no further details, but the Chinese word used to describe the interview — yuetan — generally indicates a dressing down by authorities.

Ant said, “Views regarding the health and stability of the financial sector were exchanged.”

It may have involved rather more than an exchange of views. The next day, the government summarily canceled Ant’s $37 Bn offering – which would have been the largest IPO of all time – and a long-anticipated milestone in China’s rise towards global parity in technology and finance. What happened?

The full story here has three chapters:

1. The market dynamics surrounding the offering itself

2. The dangerous business model that created the risk of a financial cataclysm, both for the company and for the entire Chinese financial system

3. The inevitable impact on Ant’s valuation (had the offering gone forward) – which would have driven a likely collapse of the shares following the IPO

This column focuses on the first of these factors: the IPO Fiasco, and the immediate concerns that led to its abrupt cancellation.

Who/What is Ant?

It is likely that many Americans still have not heard of Ant, nor would recognize its logo. That will change soon.

ANT LOGO

Ant is a high-tech Chinese financial supermarket launched just 6 years ago. It has probably grown bigger, faster, than any company in history. It is adorned with superlatives:

the world’s most highly valued Financial Technology company

the world’s largest money market fund

the world’s largest mobile and online financial payments company

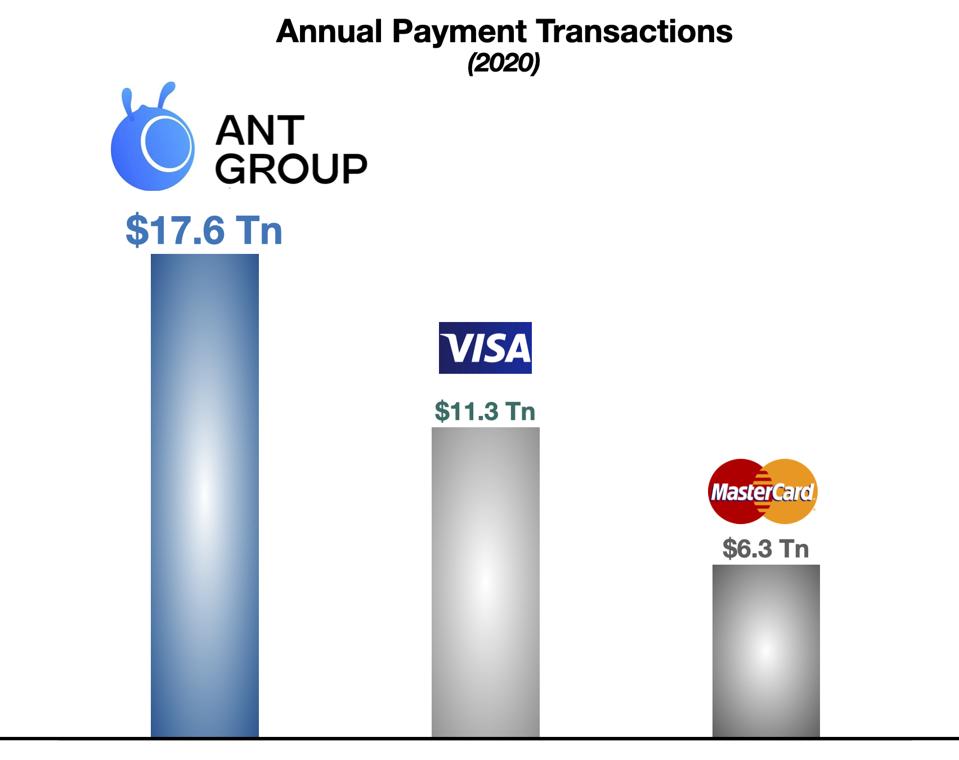

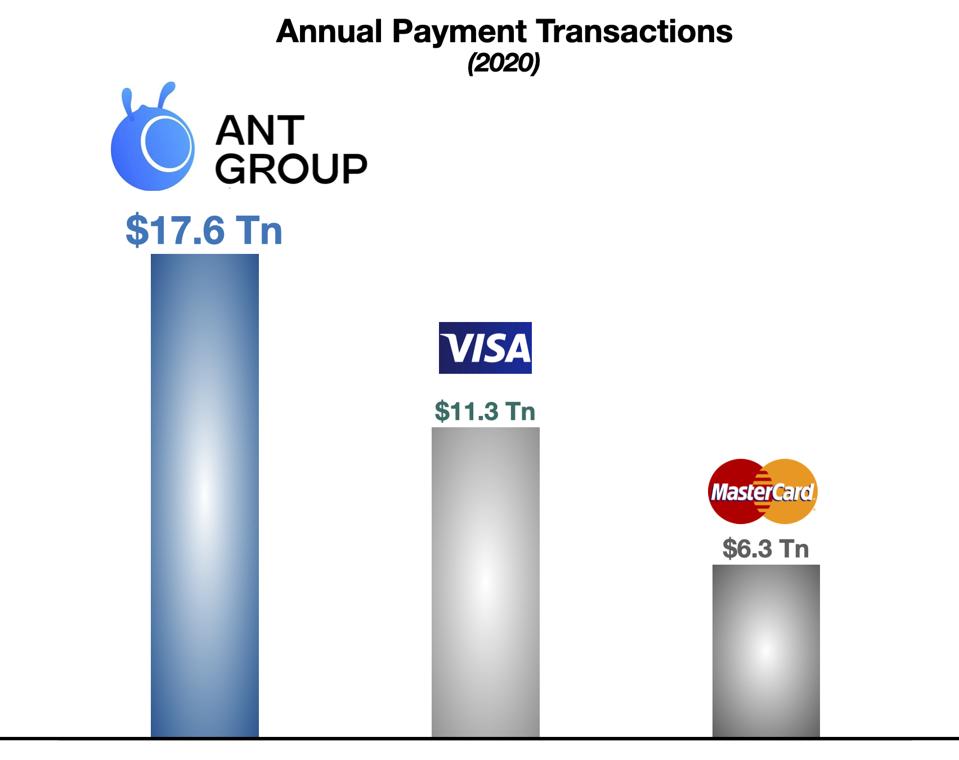

More payment transactions processed than Mastercard & Visa

Ant, Visa, Mastercard, Annual Payment Transactions CHART BY AUTHOR

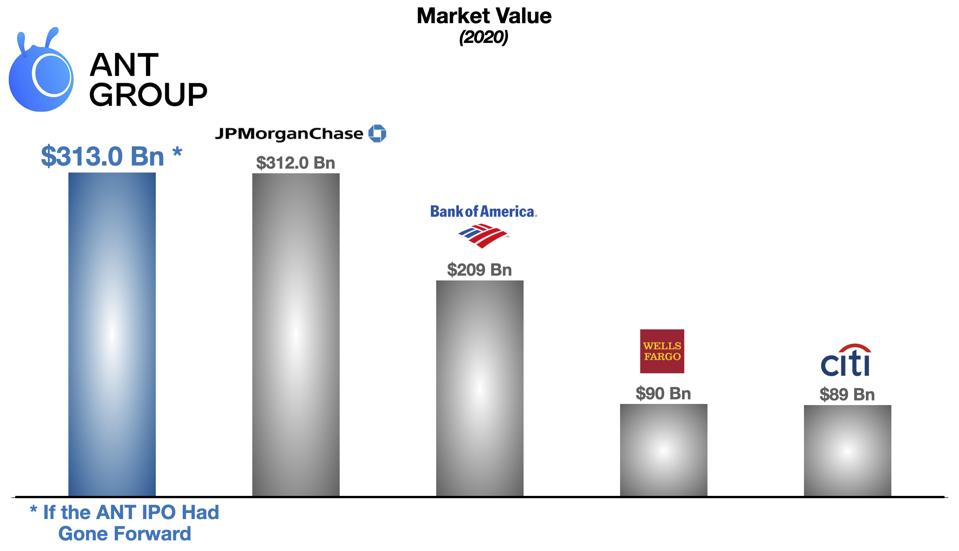

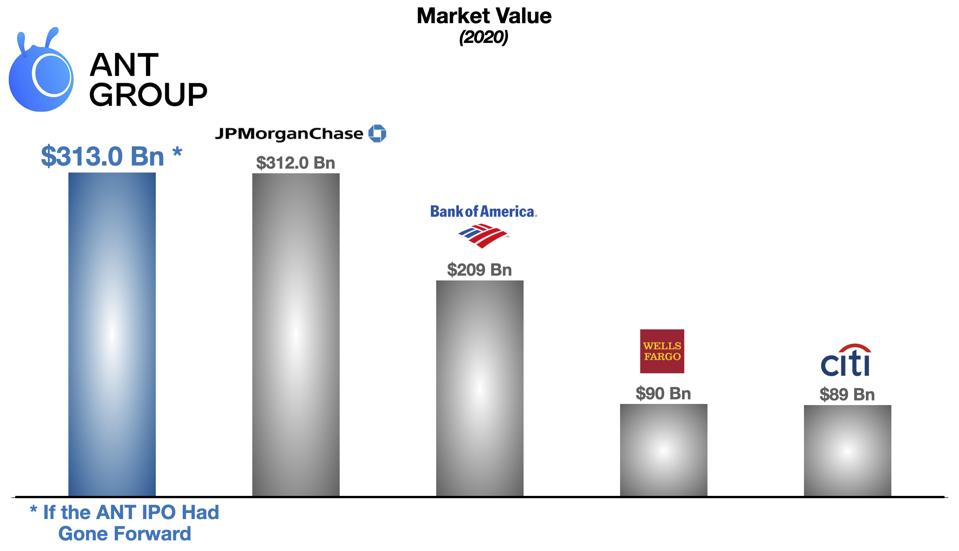

More valuable than any bank in the world (or would have been…)

Ant vs the Big American Banks – Market Value CHART BY AUTHOR

Ant has been called “a powerful symbol of the potential of China’s financial markets.” Just last month The Economist wrote:

Ant is a high-tech Chinese financial supermarket launched just 6 years ago. It has probably grown bigger, faster, than any company in history. It is adorned with superlatives:

the world’s most highly valued Financial Technology company

the world’s largest money market fund

the world’s largest mobile and online financial payments company

More payment transactions processed than Mastercard & Visa

Ant, Visa, Mastercard, Annual Payment Transactions CHART BY AUTHOR

More valuable than any bank in the world (or would have been…)

Ant vs the Big American Banks – Market Value CHART BY AUTHOR

Ant has been called “a powerful symbol of the potential of China’s financial markets.” Just last month The Economist wrote:

“More important than its size is what Ant represents. It matters globally in a way that no other Chinese financial institution does.”

As for Jack Ma, he is a celebrity entrepreneur in China comparable to Elon Musk or Bill Gates or Warren Buffett, or all three together. Considering China’s aspirations to achieve technological parity with the West, Ma is a national front-man – on a par even with Xi Jinping himself:

“It is hard to overstate the importance in China of Mr. Ma and his two companies. They have become synonymous to innovation. The media in China calls the country’s rising tech sector, ‘The era of Ma.’”

The Offering Fiasco

With all this as context – Ant’s IPO was much more than a stock offering. It was to be a statement, and a symbol, of China’s rise, “the crowning glory of a homegrown financial technology” – and at the same time, a geopolitical rebuke to American politicians and regulators who have been threatening to close U.S. stock exchanges to some Chinese companies (covered in a previous column). It was a Declaration of Independence of sorts:

“Its listing in Shanghai was intended to show that China no longer needs US capital markets to finance its world-class corporations.”

Ant was said to represent the future of banking, insurance, investment – the future of consumer finance in all its aspects, from mutual funds and money market accounts to digital currency and credit scoring – indeed, so futuristic was its business model that the idea of a mere bank seemed suddenly obsolescent and at risk. Even Western giants like Citibank and JP Morgan suddenly looked like dinosaurs, vulnerable to the new species of companies like Ant, armed with Fintech. Ant was poised to surpass them all in market value. The aura of success was palpable. Investors were already giddy. Ant shares rose 50% in the grey market in the run-up to the offering itself.

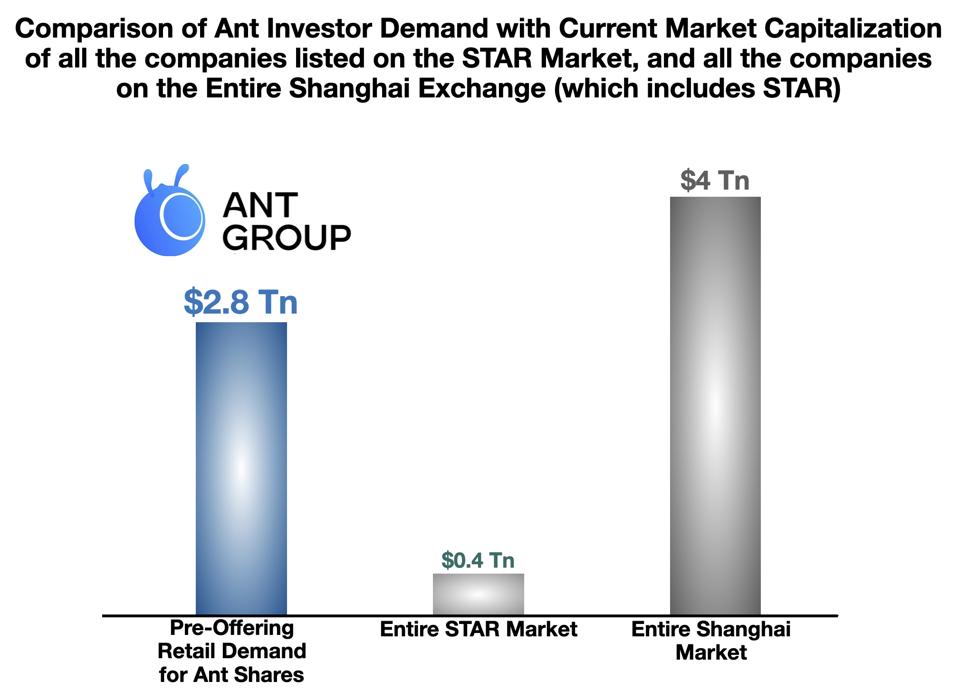

But the Ant phenomenon loomed much larger than these numbers show. The IPO itself was shaping up as a catalyst for a much larger financial earthquake. The offering was oversubscribed 870 times – $2.8 trillion of orders just from retail investors in mainland China. There would almost certainly have been an enormous “pop” in the share price following the offering. Even the sober-and-superior Wall Street Journal goggled at the size of the Ant IPO order book: “It exceeds the value of all the stocks listed on the exchanges of Germany.”

That was the state of affairs as of Friday Oct 30.

On the following Tuesday, “the most lucrative coming out party in history” was abruptly postponed, perhaps canceled. Retail investors were “shell-shocked.” Dozens of “elite” foreign investors who got in earlier were expecting an $8 Bn pay-off – which didn’t happen. The investment bankers (the usual suspects, including Goldman, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley) were out $400 million in fees.

The event became yet another Ant superlative – the biggest IPO by far ever to be withdrawn.

Why?

Of course the frenzy over the possible offering was mirrored in a new frenzy of theories about what-just-happened.

Punishment?

A common explanation was that the Chinese government had simply decided to discipline Ant, “to cut Jack Ma down to size.” Ant “was becoming a monster.” Ma was “arrogant.” His stinging public criticism aimed at China’s regulators triggered Beijing’s wrath. Indeed, speaking at a Shanghai conference a week earlier, Ma was extraordinarily blunt. He spoke of the Chinese financial establishment as a “club for the elderly.” He accused the big Chinese banks of having a “pawnshop mentality” – out-of-date and non-tech-savvy. (He had said on another occasion that he would like to make them “feel unwell.”) His broad view of the regulatory framework was scathing:

“We cannot regulate the future with yesterday’s means,” the 56-year-old Ant co-founder said at the forum. “There’s no systemic financial risks in China because there’s no financial system in China. The risks are a lack of systems.”

This could not have gone down well with the incumbents and the bureaucrats.

But does this explanation really make sense?

There is a high cost for abrupt and heavy-handed intervention in ostensibly free markets.

“Predictable regulation helps to underpin confidence in markets and the economy. Unexpected changes, especially if politically-driven, are usually damaging.” [The Financial Times]

China is trying to establish a world-class financial system. Moves that evoke memories of a Mandarin past – hostile, peremptory and perhaps predatory – would seem to undermine this effort.

“The turn of events is not just painful for Ant. It reflects poorly on China’s regulators. The last-minute halt of Ant’s listing highlights the opacity of the Chinese political system and the risks that can trip up even its most successful companies.” [The Economist]

“The ripple effects of the cancelled IPO are many — and mostly worrying. ‘The message is that no big private businessman will be tolerated on the mainland.’” [said a Hong Kong University professor]

Why would China risk impairing its strategic program for the sake of disciplining an outspoken businessman (who also happens to have built the most successful business that the country has ever produced)?

But the fact that this theory doesn’t make sense (to an outsider) doesn’t mean it isn’t true. Beijing has committed a string of such blunders recently. (Consider the Hong Kong takeover, or Beijing’s hostage diplomacy related to Huawei.) Old habits of authoritarian offense-taking persist, one supposes.

The Enmity of Vested Interests

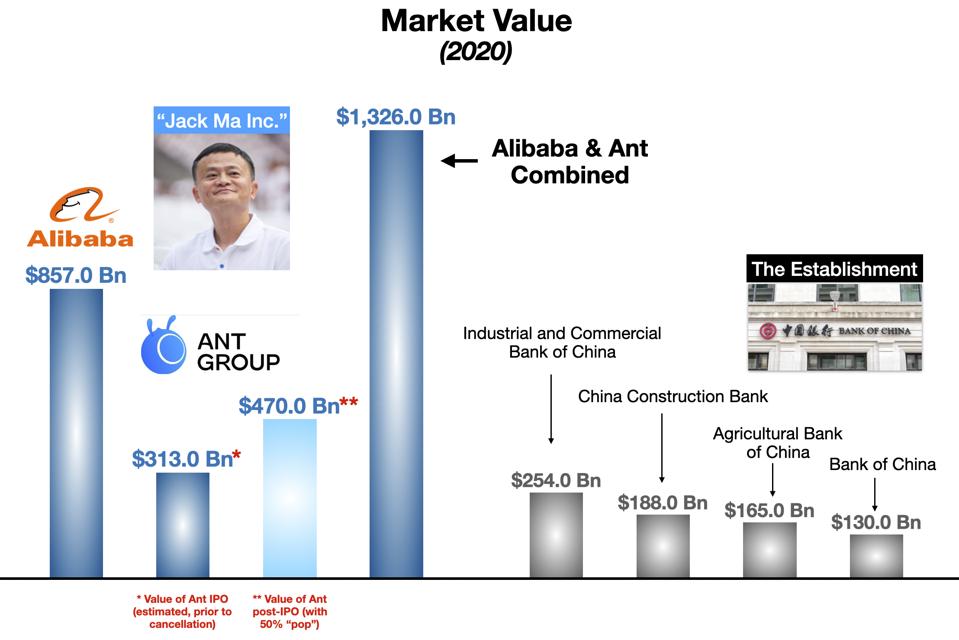

Another theory is that the big established Chinese banks — the very “pawnbrokers” Ma denounced – want to clip his wings for business reasons, and force Ant to play by their rules, and live with the same constraints. Ant is competing aggressively, and successfully, taking business from powerful incumbents, who have lobbied hard to rein him in. In fact, in the market’s view – which is always future-oriented – Ma and Ant had already won. “Jack Ma Inc.” – which includes both the Alibaba Group BABA +4.2% (the Chinese version of Amazon AMZN -0.3%, to use a very short-hand description) and the Ant Group – has far surpassed the value of the traditional Chinese banking giants.

Jack Ma Inc. vs the Establishment CHART BY AUTHOR

This explanation makes some sense too — and some nonsense. At the very least, the regulatory response seems too violent. The normal way to rein in a company like Ant, slowly and without shocking the markets, is to impose gradual new regulations (e.g., higher capital reserves, or line-of-business restrictions) or new taxes. With plenty of discussion, and time for all parties to adjust. The Financial Times points this out:

“The draft regulations, by themselves, do not explain why the IPO was suspended. In normal cases, Beijing’s regulators consult with key industry players and, when a consensus is reached, announce the new rules. That way the market impact is minimised.”

The suddenness, and the forcefulness, of this move is not the typical behavior of a bureaucratic estate, even an unfriendly one. Unless…

Panic Over A Mega-Bubble

I think there is an element of panic in this move, as though the regulators suddenly realized that a serious crisis might be imminent. The awareness of the need for swift, even violent action was brought about (I think) by the extraordinary frenzy of anticipation surrounding the offering, the trillions of dollars of buy-side interest from small investors, which meant that

a valuation bubble in Ant’s shares was about to inflate – with 870 times greater demand for the Ant shares than supply, this was very likely the millions of investors who wanted in on this deal were loading up with debt to purchase their shares – up to 95% leverage – exposing them to great losses when… those small investors would be the ones who bought into the backend of the upwards price spiral, paying the highest prices with borrowed money

the flaws in the company’s business model became clear to the market, driving a severe downward re-valuation – triggering massive margin calls and huge losses

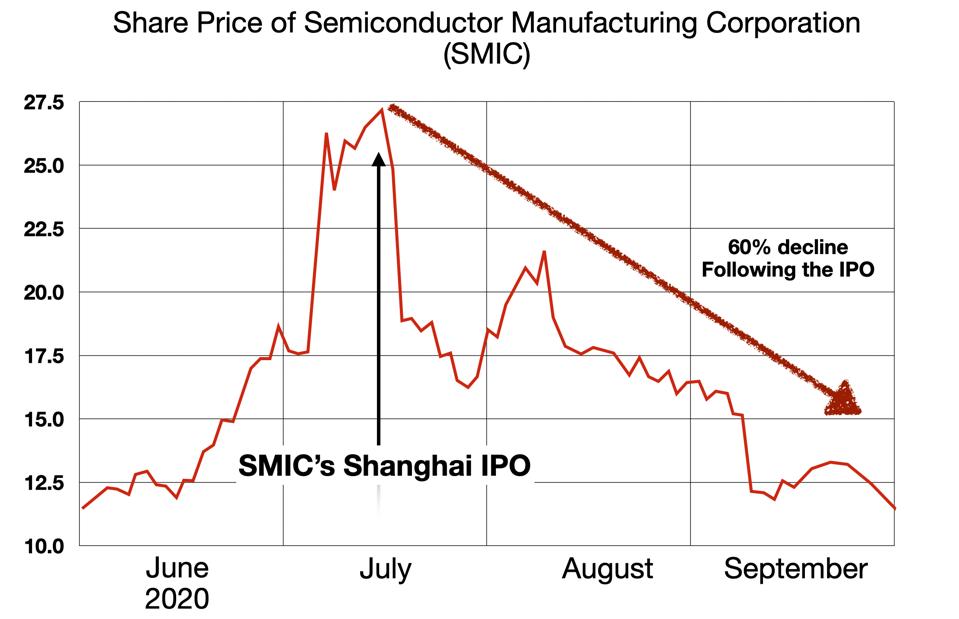

This scenario is not imaginary. This summer, the Shanghai STAR Market IPO for China’s leading chip maker (SMIC) was also oversubscribed. The company nearly tripled in value on the first day of trading – only to fall back as its business realities began to sink in. The losers were largely retail investors who bought into the excitement of the new listing.

This scenario is not imaginary. This summer, the Shanghai STAR Market IPO for China’s leading chip maker (SMIC) was also oversubscribed. The company nearly tripled in value on the first day of trading – only to fall back as its business realities began to sink in. The losers were largely retail investors who bought into the excitement of the new listing.

SMIC Rise and Fall CHART BY AUTHOR

This pattern is common in China today.

“Orders for some share sales have been thousands of times the stock on offer, and some stocks have surged as much as 10-fold on their first day. In another sign of exuberance, some Shanghai prices are far removed from those of the same shares listed elsewhere. [At the height of the frenzy] SMIC’s Shanghai stock price was roughly three times its Hong Kong stock price.”

I think that the Chinese authorities suddenly realized that this same scenario was likely to develop out of the Ant offering. Market dislocations, excessive leverage, extreme price spikes, big losses for small investors. The Ant IPO was to have been 6 times the size of SMIC’s IPO. But that was just the tip of the iceberg – remember that the nearly $3 trillion of retail demand was stacked up behind the opening, ready to explode into the stock, and blow prices upwards. Remember that this was more than “the value of all the stocks listed on the exchanges of Germany.” In fact, the investor demand for Ant shares was 7 times greater than the total value of the companies traded on the Nasdaq-like Star exchange in Shanghai.

Comparison of Ant Investor Demand with the Market Cap of the entire STAR Market and the Shanghai ... [+] CHART BY AUTHOR

The prospect of much broader market instability loomed. This is what suddenly panicked the bosses in Beijing.

As to what it was about Ant’s business that triggered their concern... that is the subject of the next installment.

George Calhoun's new book is Price & Value: A Guide to Equity Market Valuation Metrics (Springer 2020). Prof. Calhoun can be contacted at gcalhoun@stevens.edu

Founder & Director of the Quantitative Finance Program and Hanlon Financial Systems Center at the Stevens Institute of Technology (New Jersey) and Advisory Board Member at Hanlon Investment Management

No comments:

Post a Comment