As Philippines seeks Covid-19 vaccines, ghost of Dengvaxia controversy lingers

In 1990, nine in 10 Filipinos believed in the importance of vaccines – a trend that’s reversed in recent years following controversy over a dengue vaccine

As Covid-19 cases rise in one of the region’s worst-hit nations, low public trust in vaccines will be a huge hurdle in the government’s vaccination bid

A health worker conducts a mock Covid-19 vaccination during a simulation exercise in Manila. Photo: Reuters

“Vaccination? Not me, I don’t want it,” said Carlito Cristo Niniado, 68, a carpenter in Manila.

He said he had read that 23 people abroad died after receiving Pfizer’s

coronavirus vaccine. “If I don’t die of Covid, I’ll die of vaccination. It’s better not to take chances.”

Niniado is far from a lone voice in the

Philippines, where public trust in immunisations has for several years been at an all-time low, after a controversy over a dengue vaccine sparked widespread panic and a loss of faith in immunisation.

The challenge of convincing Filipinos to take the Covid-19 shots will be a huge hurdle for the Philippine government, which is already plagued by accusations of disorganisation, delay and corruption, as it readies vaccine orders to inoculate 108 million people.

Delays and missteps: how Duterte’s Philippines struggled against Covid-19

31 Dec 2020

In November, a poll conducted by Pulse Asia Research Inc showed that only 32 per cent of respondents in the Philippines were willing to receive a Covid-19 vaccine.

Almost half of the 2,400 people surveyed said they would skip immunisation, while 21 per cent could not say what their decision was. Many of those who didn’t want to get inoculated said the main reason was they were not certain of the vaccine’s safety.

In 2019, the World Health Organization listed vaccine hesitancy – the refusal to take vaccines – as one of the top 10 threats to global health.

Filipinos were not always hostile to vaccines: in the 2015 Global Vaccine Confidence Index, 93 per cent of Filipinos surveyed agreed that vaccines were important.

It was a confidence decades old, an expert said.

“Way back in 1990, we had the highest vaccine confidence in the maps of the world,” said Dr Lulu Bravo, executive director of the Philippine Foundation for Vaccination. “We had 5 to 8 million children vaccinated from 1981 to 1993. There was no problem at all – we were able to eradicate polio.”

Then in 2019, trust in immunisation “plummeted”, she said.

What happened was what Health Secretary Francisco Duque III called a “very unfortunate experience”.

Why the Philippines suspended a world-first dengue vaccine

20 Jul 2018

In 2015, the administration of then-President Benigno Aquino III started a major 3 billion peso (US$151 million) campaign against dengue with Dengvaxia, a vaccine made by the French company Sanofi. In 2017, Sanofi made a shock announcement that its vaccine could be dangerous if administered to people who had never been exposed to dengue.

By then, some 700,000 children had been inoculated, said Dr Anthony Leachon, a health reform advocate and a former senior adviser to the country’s Covid-19 task force.

The news triggered outrage in the Philippines, prompting congressional investigations which were played out in a series of hearings that mixed medical facts, hysteria, political posturing and melodrama.

Families stepped forward to claim their children had died after receiving a Dengvaxia jab, an unsubstantiated narrative which spread online like wildfire, and one that the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO) pushed during the hearings. There were reports health officials advocated the use of Dengvaxia in exchange for commissions and kickbacks.

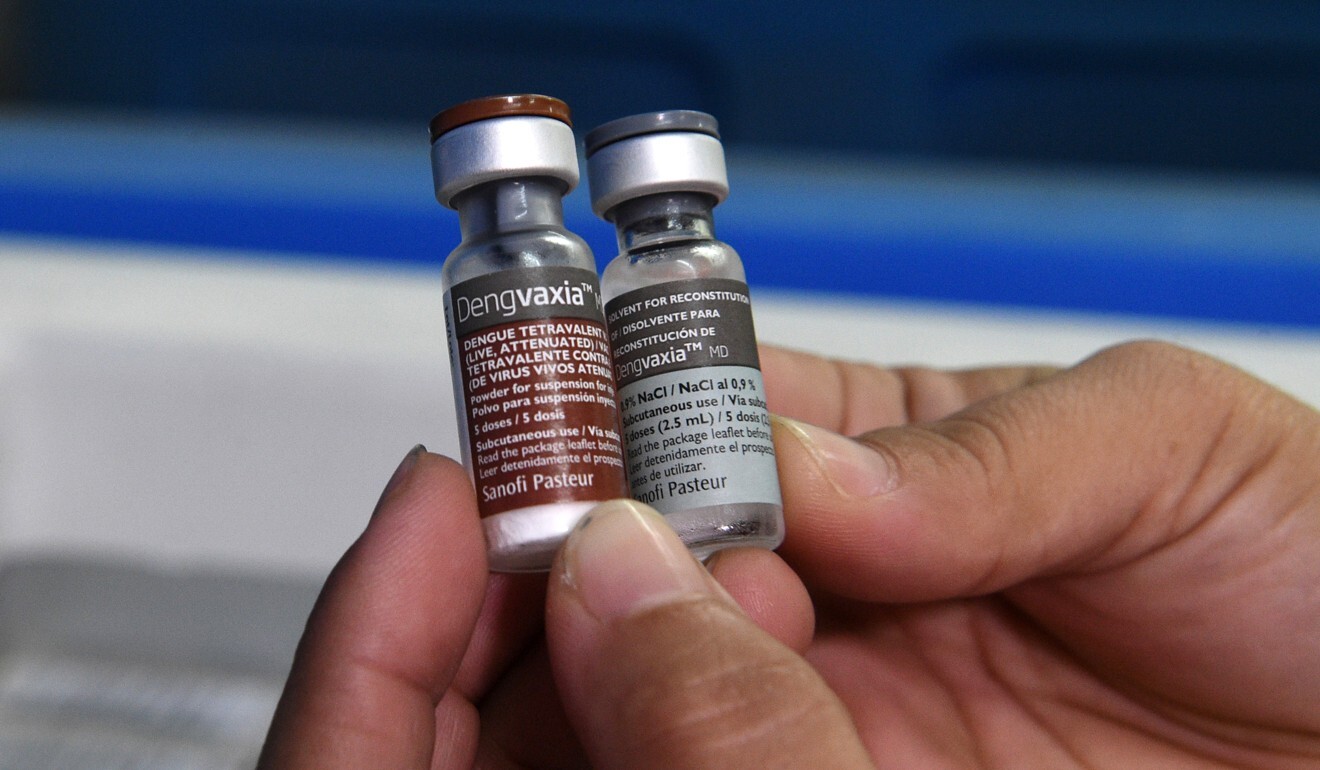

A medical worker displays vials of Sanofi’s dengue vaccine Dengvaxia. File photo: AFP

“Every day, there would be news of another death from Dengvaxia, and the PAO would get a lot of media exposure that they had been asked by parents for autopsies of children who died,” said Bravo, who was sceptical of the claim that many people died. “If you were to ask me, no one died. PAO would say hundreds.”

Medical professionals became a public enemy. “The scientists were vilified, trolled, insulted. I got my own share of that,” she said.

After one congressional hearing in 2018, a mother screamed “you killed my child” and attempted to attack former Health Secretary Janette Garin. The woman later admitted her child had not actually died.

Are Philippine children’s deaths linked to dengue vaccine?

22 Apr 2019

Critics of the proceedings said the Duterte administration used the hearings as a pretext to jail Aquino. But Leachon, a former medical director at Pfizer, said the backlash against Dengvaxia was justified.

He referred to a 2018 letter written by a group of Filipino doctors that pointed out the errors the authorities had made in handling Dengvaxia: multisectoral stakeholders were not consulted, there was no public education and the project was rushed.

“The programme was too hasty. Usually there’s a playbook; you need to prepare the community for three to six months before launching a national vaccination programme,” Leachon said.

He added that while it could not be determined if Dengvaxia had directly caused any deaths, “we can say there was proximate cause” – at least two people who were vaccinated later died.

I am sure we have the highest level of vaccine hesitancy in the Asia-Pacific region because of the Dengvaxia issue

Dr Lulu Bravo, Philippine Foundation for Vaccination

At the end of the hearings, Aquino and some officials faced cases of plunder and graft because the Dengvaxia programme allegedly didn’t follow government procurement rules and there was “unseemly haste” in implementing it, while cases of negligence resulting in homicide were filed against other executives, including those involved in the vaccine clinical trials.

But beyond that, it also caused a mass distrust of vaccines that led to a spike in preventable deaths. Some fearful parents all but barricaded their children, refusing to have them inoculated. Diseases that had been eradicated began reappearing.

“In 2000, the Philippines was declared polio-free. In September 2019, we got the first report of polio followed by other cases,” Bravo said.

“We had a measles outbreak in January 2019. By April, there were about 500 deaths from measles,” she added. In comparison, “starting 2005 there were zero deaths from measles”.

The Philippines on dengue fever alert as 2019 outbreak death toll nears 500

“I am sure we have the highest level of vaccine hesitancy in the Asia-Pacific region because of the Dengvaxia issue,” Bravo said.

She acknowledged, however, that “a lot of scientists may also have been at fault, by not communicating well” the benefits and risks of Dengvaxia.

Now, with Covid-19 infections rising in one of Southeast Asia’s worst-hit countries, reaching some 511,000 cases on Saturday, the shadow of Dengvaxia hangs heavily over the proposed immunisation effort. Bravo called it “the elephant in the room”.

‘BFF prices’, no corruption: Manila defends deal with China’s Sinovac

18 Jan 2021

To reduce vaccine resistance, Leachon said the government should consult the ground and take residents’ concerns into account.

“They need to survey people and ask them, are you willing to be vaccinated? If yes, what are the reasons, and also, what particular vaccine do you want? Some local governments are already doing this,” he said

In the city of Cainta in Rizal province, residents indicated they did not want Chinese-made vaccines, said Leachon.

In early January, Health Secretary Duque told senators in a hearing that there would be a “massive social marketing campaign” to convince Filipinos to immunise themselves against Covid-19.

Senate President Vicente Sotto III had earlier warned Duque that the government was losing the information battle on social media. “You’re being defeated by those [messages claiming that people] are being vaccinated and they speak Chinese afterwards,” he was quoted by GMA News as saying.

Health workers check the temperature and blood pressure of a woman during a simulation exercise for Covid-19 vaccination efforts in Manila. Photo: Reuters

Bravo said the vaccination effort this time should involve medical societies, the private sector, non-government organisations, communities and academics.

The Dengvaxia controversy continues to take its toll on her. A staunch advocate of vaccines, she has been among the doctors pilloried and accused of being in the pocket of drug companies.

“When facing the media I have to pray, I have to pray a lot,” she said. “That has been the curse of Dengvaxia”.

No comments:

Post a Comment