After battling Covid-19 for three weeks in hospital, Faithfull went on to finish her 21st solo album – and possibly her last.

Friends occasionally tried to help, but it wasn’t until 1979 that she recovered enough to make the astonishing Broken English, an album on which Faithfull suddenly appeared to spring back to life, fangs bared. Its songs were about addiction, terrorism and infidelity – the closing Why D’Ya Do It was so explicit in its description of an affair that workers at EMI walked out, refusing to press the album – or depicted Faithfull as the ghost at the feast of 60s nostalgia. “I made a decision to really, completely give my heart to the whole thing, and that’s what happened. I was quite smart enough to realise that I had a lot to learn. You know, I didn’t go to Oxford, but I went to Olympic Studios and watched the Rolling Stones record, and I watched the Beatles record as well. I watched the best people working and how they worked and, because of Mick, I guess, I watched people writing, too – a brilliant artist at the top of his game. I watched how he wrote and I learned a lot, and I will always be grateful.”

She reflects on how she might never sing again, her hatred of being a 60s muse and why she still believes in miracles

by Alexis Petridis THE GUARDIAN

Fri 15 Jan 2021

Marianne Faithfull is on the phone from her home in Putney, south-west London. She sounds exactly like you would expect: as husky as her singing on every album she has made for the past 40 years and, as the daughter of a baroness, very posh. Her vocabulary is unmistakably that of someone who came of age in the 1960s: exasperation is expressed in sentences that begin: “Oh, man…”; things that vex her are “a drag”. But before we begin, she offers a pre-emptive apology. Her memory, she says, isn’t what it was. “It’s wild, the things I forget,” she says. “Short-term. I remember the distant past very well. It’s recent things I can’t remember. And that’s ghastly. Awful. You wouldn’t believe how awful it is.”

The memory loss is a result of Covid-19. She was in something of a purple patch in her career when the virus struck last April, midway through recording her 21st solo album She Walks in Beauty, and with a biopic based on her 1994 autobiography in the works (“It could be really good,” she says of the latter, “but it doesn’t require my artistic input – I lived the life, that’s enough”). She doesn’t remember anything about falling ill, or being rushed to intensive care: “All I know is that I was in a very dark place – presumably, it was death.”

In the outside world, obituaries were prepared. It wasn’t just ghoulish journalists who assumed Faithfull’s luck – which in the past had seen her through heroin addiction, bulimia, suicide bids, homelessness, breast cancer, hepatitis C and, in 2014, a broken hip that became infected after surgery – had finally run out. She was, by her own admission, very much Covid-19’s target market: 73 years old, with a raft of underlying health conditions, including emphysema, the result of decades of smoking. “Oh man,” she sighs today. “I wish I’d never picked up a cigarette in my life.”

“She wasn’t actually meant to make it through,” says her musical collaborator, Warren Ellis, best known as Nick Cave’s chief foil in the Bad Seeds. “That she survived it – it’s insane.” Her situation seemed so grim that Ellis received a concerned text about her welfare from her long-term friend and producer Hal Willner, himself ill with Covid: Willner died of the virus the day after it was sent. Her management put out a statement saying she was responding well to treatment, but Faithfull says that in hospital, the doctors took a less optimistic approach. Once recovered, she read her medical notes and found the phrase “palliative care only”.

Incredibly, she quickly returned to work, completing She Walks in Beauty, which perhaps says something about her passion for the album coming out in April, an unexpected project even given her eclectic latter-day solo discography, which has involved reinterpreting Kurt Weill’s 1933 ballet chanté The Seven Deadly Sins, collaborating with Blur and Pulp, and covering everyone from Duke Ellington to Black Rebel Motorcycle Club. On She Walks in Beauty, Faithfull reads the work of the Romantic poets – Keats’ To Autumn, and Ode to a Nightingale; Shelley’s Ozymandias; Wordsworth’s Prelude – to backings provided by Ellis, with contributions from Brian Eno and Nick Cave.

She was first drawn to the poems at school. “Well, it’s fairly obvious, isn’t it?” she chuckles. “I was a clever girl, a pretty girl, and I thought they were all about me.” She wanted to record them “for a long time, but I could never think of how, and what record company would ever want to put it out; who would even want to hear it. Even I thought about it commercially, and that’s never been my way. I just couldn’t imagine it. But then finally, really because of Warren and my manager François, I saw that I could do it now and – this is terrible – but it’s perfect for what we’re all going through. It’s the most perfect thing for this moment in our lives. We recorded it in lockdown, and I thought so as I was doing it. I found it very comforting and very kind of beautiful. Now when I read them, I see eternity – they’re like a river or a mountain, they’re beautiful and comforting. I have,” she adds with a throaty chuckle, “realised they’re not about me.”

Her last album, 2018’s Negative Capability, was another collaboration with Ellis and an extraordinary meditation on ageing, loneliness and loss, not least that of Anita Pallenberg, her old friend and fellow former Rolling Stones paramour, who died in 2017. It featured a re-recording of her Mick Jagger and Keith Richards-penned debut single As Tears Go By that, Ellis says, reduced everyone else in the studio to tears. The album understandably received rapturous reviews, which led Faithfull to claim that Britain “finally understood who I am and what I’m trying to do, which I’ve been waiting for all my life”.

I really annoyed people, somehow. I wasn’t a conventional artist and they couldn’t handle it, didn’t want it to be true

“I really annoyed people, I think, somehow,” she says now, referring to much of her career. “Maybe just everything about me was annoying at the time. You know, I wasn’t a conventional artist, ever, and also, it was kind of clear that it wasn’t an affectation and it just annoyed people, I think. They couldn’t handle it, they just didn’t want it to be true.”

She had sung around folk clubs in Reading as a teenager but says she had no desire to be a pop singer. “Oh man, I was really happy. I was going to go to Cambridge or Oxford and study English literature, philosophy and comparative religion. I remember when I said that to people at the time, they were appalled! But I didn’t do that, did I? Look what I actually did! I fulfilled all their wildest fantasies.”

by Alexis Petridis THE GUARDIAN

Fri 15 Jan 2021

Marianne Faithfull is on the phone from her home in Putney, south-west London. She sounds exactly like you would expect: as husky as her singing on every album she has made for the past 40 years and, as the daughter of a baroness, very posh. Her vocabulary is unmistakably that of someone who came of age in the 1960s: exasperation is expressed in sentences that begin: “Oh, man…”; things that vex her are “a drag”. But before we begin, she offers a pre-emptive apology. Her memory, she says, isn’t what it was. “It’s wild, the things I forget,” she says. “Short-term. I remember the distant past very well. It’s recent things I can’t remember. And that’s ghastly. Awful. You wouldn’t believe how awful it is.”

The memory loss is a result of Covid-19. She was in something of a purple patch in her career when the virus struck last April, midway through recording her 21st solo album She Walks in Beauty, and with a biopic based on her 1994 autobiography in the works (“It could be really good,” she says of the latter, “but it doesn’t require my artistic input – I lived the life, that’s enough”). She doesn’t remember anything about falling ill, or being rushed to intensive care: “All I know is that I was in a very dark place – presumably, it was death.”

In the outside world, obituaries were prepared. It wasn’t just ghoulish journalists who assumed Faithfull’s luck – which in the past had seen her through heroin addiction, bulimia, suicide bids, homelessness, breast cancer, hepatitis C and, in 2014, a broken hip that became infected after surgery – had finally run out. She was, by her own admission, very much Covid-19’s target market: 73 years old, with a raft of underlying health conditions, including emphysema, the result of decades of smoking. “Oh man,” she sighs today. “I wish I’d never picked up a cigarette in my life.”

“She wasn’t actually meant to make it through,” says her musical collaborator, Warren Ellis, best known as Nick Cave’s chief foil in the Bad Seeds. “That she survived it – it’s insane.” Her situation seemed so grim that Ellis received a concerned text about her welfare from her long-term friend and producer Hal Willner, himself ill with Covid: Willner died of the virus the day after it was sent. Her management put out a statement saying she was responding well to treatment, but Faithfull says that in hospital, the doctors took a less optimistic approach. Once recovered, she read her medical notes and found the phrase “palliative care only”.

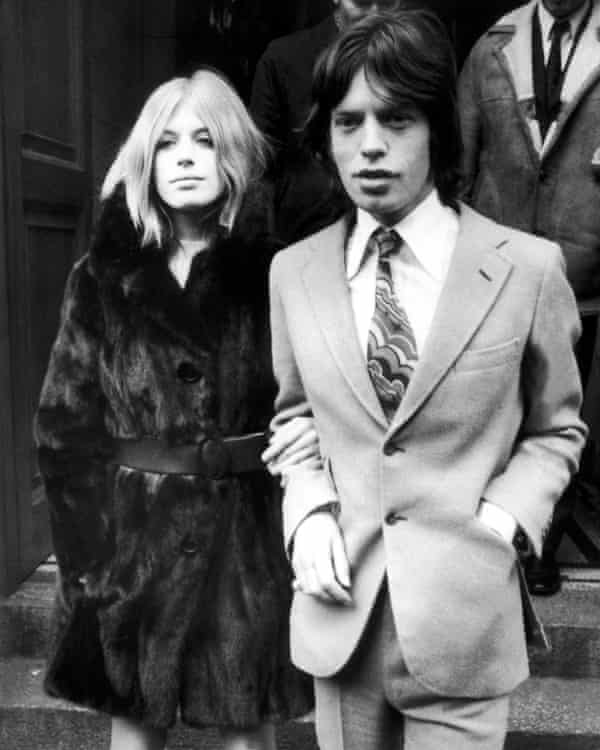

'A muse? That’s a terrible job’ … Faithfull in 1967. Photograph: Marc Sharratt/REX/Shutterstock

Yet she did recover, albeit with lasting effects. “Three things: the memory, fatigue and my lungs are still not OK – I have to have oxygen and all that stuff. The side-effects are so strange. Some people come back from it but they can’t walk or speak. Awful.”

Yet she did recover, albeit with lasting effects. “Three things: the memory, fatigue and my lungs are still not OK – I have to have oxygen and all that stuff. The side-effects are so strange. Some people come back from it but they can’t walk or speak. Awful.”

Incredibly, she quickly returned to work, completing She Walks in Beauty, which perhaps says something about her passion for the album coming out in April, an unexpected project even given her eclectic latter-day solo discography, which has involved reinterpreting Kurt Weill’s 1933 ballet chanté The Seven Deadly Sins, collaborating with Blur and Pulp, and covering everyone from Duke Ellington to Black Rebel Motorcycle Club. On She Walks in Beauty, Faithfull reads the work of the Romantic poets – Keats’ To Autumn, and Ode to a Nightingale; Shelley’s Ozymandias; Wordsworth’s Prelude – to backings provided by Ellis, with contributions from Brian Eno and Nick Cave.

She was first drawn to the poems at school. “Well, it’s fairly obvious, isn’t it?” she chuckles. “I was a clever girl, a pretty girl, and I thought they were all about me.” She wanted to record them “for a long time, but I could never think of how, and what record company would ever want to put it out; who would even want to hear it. Even I thought about it commercially, and that’s never been my way. I just couldn’t imagine it. But then finally, really because of Warren and my manager François, I saw that I could do it now and – this is terrible – but it’s perfect for what we’re all going through. It’s the most perfect thing for this moment in our lives. We recorded it in lockdown, and I thought so as I was doing it. I found it very comforting and very kind of beautiful. Now when I read them, I see eternity – they’re like a river or a mountain, they’re beautiful and comforting. I have,” she adds with a throaty chuckle, “realised they’re not about me.”

Her last album, 2018’s Negative Capability, was another collaboration with Ellis and an extraordinary meditation on ageing, loneliness and loss, not least that of Anita Pallenberg, her old friend and fellow former Rolling Stones paramour, who died in 2017. It featured a re-recording of her Mick Jagger and Keith Richards-penned debut single As Tears Go By that, Ellis says, reduced everyone else in the studio to tears. The album understandably received rapturous reviews, which led Faithfull to claim that Britain “finally understood who I am and what I’m trying to do, which I’ve been waiting for all my life”.

I really annoyed people, somehow. I wasn’t a conventional artist and they couldn’t handle it, didn’t want it to be true

“I really annoyed people, I think, somehow,” she says now, referring to much of her career. “Maybe just everything about me was annoying at the time. You know, I wasn’t a conventional artist, ever, and also, it was kind of clear that it wasn’t an affectation and it just annoyed people, I think. They couldn’t handle it, they just didn’t want it to be true.”

She had sung around folk clubs in Reading as a teenager but says she had no desire to be a pop singer. “Oh man, I was really happy. I was going to go to Cambridge or Oxford and study English literature, philosophy and comparative religion. I remember when I said that to people at the time, they were appalled! But I didn’t do that, did I? Look what I actually did! I fulfilled all their wildest fantasies.”

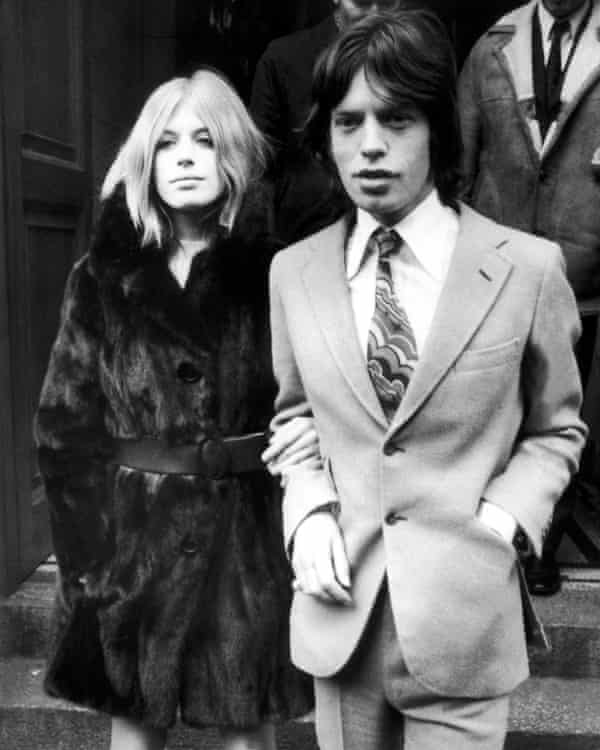

Leaving court with Mick Jagger after the couple were charged for cannabis possession, 1969.

Photograph: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Her career in academia came to an end the night she went to a party thrown by the Rolling Stones in the company of her soon-to-be first husband, John Dunbar. She was spotted by the Stones’ manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, who dismissed her as “an angel with big tits” yet thought he could mould her into a star. “It was a terrible idea,” she says today. “It took me a long time to get over the resentment I had towards Andrew Loog Oldham, and [Oldham’s business partner] Tony Calder and even Mick and Keith. You know, I loved Mick and Keith, and Charlie, and Ronnie actually, but … it took me years before I accepted it, that this was me, that I was meant to do this, it was my destiny, my fate.”

She had reason to feel resentful. Indeed, if you want to while away some of your lockdown hours boggling at the sexism of the 60s music industry, Faithfull’s story is a good place to start. She was, as she later put it, treated “as somebody who not only can’t even sing, but doesn’t really write or anything, just something you can make into something. I was just cheesecake, really, terribly depressing.” Oldham seems to have seen her primarily as a means of living out his fantasies of becoming a British Phil Spector with a stable of stars to match. Faithfull would be a repository for any surplus material Jagger and Richards might write, and a light entertainer: a pretty, posh girl whose niche would be essaying folk songs for a Saturday night variety show audience.

At their worst, the results were catastrophic, but occasionally, something of Faithfull shone through, a wintry melancholy that powered her 1965 singles This Little Bird and Go Away From My World, where her vocal injected rather too much sadness and yearning into theoretically lightweight songs. “Yes, tristesse,” she says. “It’s part of me! I don’t know where it came from. Maybe it’s my star sign, although I don’t particularly believe in all of that. It’s just my character.”

But her singing career ground to a halt in 1967. She spent the rest of the decade famous – and after the drug bust at Richards’ country estate, Redlands, infamous – for being Jagger’s girlfriend or, at best, a muse, the woman who gave him a copy of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, planting the seed for Sympathy for the Devil; the inspiration behind Wild Horses, Dear Doctor and You Can’t Always Get What You Want. “A muse? That’s a shit thing to be,” she snorts. “It’s a terrible job. You don’t get any male muses, do you? Can you think of one? No.”

Photograph: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Her career in academia came to an end the night she went to a party thrown by the Rolling Stones in the company of her soon-to-be first husband, John Dunbar. She was spotted by the Stones’ manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, who dismissed her as “an angel with big tits” yet thought he could mould her into a star. “It was a terrible idea,” she says today. “It took me a long time to get over the resentment I had towards Andrew Loog Oldham, and [Oldham’s business partner] Tony Calder and even Mick and Keith. You know, I loved Mick and Keith, and Charlie, and Ronnie actually, but … it took me years before I accepted it, that this was me, that I was meant to do this, it was my destiny, my fate.”

She had reason to feel resentful. Indeed, if you want to while away some of your lockdown hours boggling at the sexism of the 60s music industry, Faithfull’s story is a good place to start. She was, as she later put it, treated “as somebody who not only can’t even sing, but doesn’t really write or anything, just something you can make into something. I was just cheesecake, really, terribly depressing.” Oldham seems to have seen her primarily as a means of living out his fantasies of becoming a British Phil Spector with a stable of stars to match. Faithfull would be a repository for any surplus material Jagger and Richards might write, and a light entertainer: a pretty, posh girl whose niche would be essaying folk songs for a Saturday night variety show audience.

At their worst, the results were catastrophic, but occasionally, something of Faithfull shone through, a wintry melancholy that powered her 1965 singles This Little Bird and Go Away From My World, where her vocal injected rather too much sadness and yearning into theoretically lightweight songs. “Yes, tristesse,” she says. “It’s part of me! I don’t know where it came from. Maybe it’s my star sign, although I don’t particularly believe in all of that. It’s just my character.”

But her singing career ground to a halt in 1967. She spent the rest of the decade famous – and after the drug bust at Richards’ country estate, Redlands, infamous – for being Jagger’s girlfriend or, at best, a muse, the woman who gave him a copy of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, planting the seed for Sympathy for the Devil; the inspiration behind Wild Horses, Dear Doctor and You Can’t Always Get What You Want. “A muse? That’s a shit thing to be,” she snorts. “It’s a terrible job. You don’t get any male muses, do you? Can you think of one? No.”

SHE WAS A BAD GURL, A FEMME FATALE FER SHURE BUT NEVER A MUSE

In The Girl on a Motorcycle, 1968.

Photograph: Allstar/ARES PRODUCTION

Her record label withdrew her gritty 1969 single Something Better, horrified by its B-side Sister Morphine, a depiction of addiction so bleak it was evidently written by someone who knew of what they spoke. When the Rolling Stones recorded it, they removed her name from the writing credits, ostensibly because they knew any money she made from it would be spent on drugs (they eventually reinstated her name in the 1990s). She broke up with Jagger and slid further into addiction. She lost custody of Nicholas, her son by John Dunbar; she says her decision to move back to London from Paris a couple of years ago was driven by a desire to be nearer her son and grandchildren, “because I deserted him for all that time, I was terribly unhappy about him being taken away from me, but it’s time to forgive and get over it and be here for him and my lovely grandchildren”.

Photograph: Allstar/ARES PRODUCTION

Her record label withdrew her gritty 1969 single Something Better, horrified by its B-side Sister Morphine, a depiction of addiction so bleak it was evidently written by someone who knew of what they spoke. When the Rolling Stones recorded it, they removed her name from the writing credits, ostensibly because they knew any money she made from it would be spent on drugs (they eventually reinstated her name in the 1990s). She broke up with Jagger and slid further into addiction. She lost custody of Nicholas, her son by John Dunbar; she says her decision to move back to London from Paris a couple of years ago was driven by a desire to be nearer her son and grandchildren, “because I deserted him for all that time, I was terribly unhappy about him being taken away from me, but it’s time to forgive and get over it and be here for him and my lovely grandchildren”.

Marianne’s genuinely awesome, a one-off. She hasn’t slipped into a nostalgia act – she shoots straight from the hip Warren Ellis

Friends occasionally tried to help, but it wasn’t until 1979 that she recovered enough to make the astonishing Broken English, an album on which Faithfull suddenly appeared to spring back to life, fangs bared. Its songs were about addiction, terrorism and infidelity – the closing Why D’Ya Do It was so explicit in its description of an affair that workers at EMI walked out, refusing to press the album – or depicted Faithfull as the ghost at the feast of 60s nostalgia. “I made a decision to really, completely give my heart to the whole thing, and that’s what happened. I was quite smart enough to realise that I had a lot to learn. You know, I didn’t go to Oxford, but I went to Olympic Studios and watched the Rolling Stones record, and I watched the Beatles record as well. I watched the best people working and how they worked and, because of Mick, I guess, I watched people writing, too – a brilliant artist at the top of his game. I watched how he wrote and I learned a lot, and I will always be grateful.”

With Warren Ellis. Photograph: Rosie Matheson

It began the second act of Faithfull’s recording career, in which she has displayed both an admirable artistic restlessness – “Well, what have I got to lose?” she laughs when I suggest she seems to have got musically bolder with age – and a marked ability to attract a rather hipper class of collaborator than you suspect most of her 60s peers could muster. As well as Pulp, Blur and Nick Cave and sundry Bad Seeds, she has worked with Beck, PJ Harvey, Anna Calvi, the Clash’s Mick Jones, Lou Reed, Cat Power and Anohni. “I know,” she says. “I’m very lucky. I don’t know what it is, but it is there, and they are hipper, cooler and even more attractive.”

“She’s real,” suggests Warren Ellis. “She’s genuinely awesome, and she’s like a one-off. Everything you think she is, she is. She’s kind of unique in that she’s remained relevant; she hasn’t sort of slipped into some kind of nostalgia act. She’s very witty, she’s intelligent and she’s extraordinary, too, because she’s lived a life – she was like a trailblazer for so many people without even knowing it. There’s no kind of mould for her career. And whatever she tells you, it’s true: she shoots straight from the hip.”

Ellis says that She Walks in Beauty is the album Faithfull has “wanted to make all her life”. There’s a chance that it might also be her last: the after-effects of Covid on her lungs mean she is currently unable to sing. “And I may not be able to sing ever again,” she says. “Maybe that’s over. I would be incredibly upset if that was the case, but, on the other hand, I am 74. I don’t feel cursed and I don’t feel invincible. I just feel fucking human. But what I do believe in, which gives me hope, I do believe in miracles. You know, the doctor, this really nice National Health doctor, she came to see me and she told me that she didn’t think my lungs would ever recover. And where I finally ended up is: OK, maybe they won’t, but maybe, by a miracle, they will. I don’t know why I believe in miracles. I just do. Maybe I have to, the journey I’ve been on, the things that I’ve put myself through, that I’ve got through so far and I’m OK. Does that sound really corny?”

No, I say, I don’t think it sounds corny. It sounds hopeful. “Yes,” she says. “We must be hopeful – it’s really important. And I am, yes. I’m bloody still here.”

It began the second act of Faithfull’s recording career, in which she has displayed both an admirable artistic restlessness – “Well, what have I got to lose?” she laughs when I suggest she seems to have got musically bolder with age – and a marked ability to attract a rather hipper class of collaborator than you suspect most of her 60s peers could muster. As well as Pulp, Blur and Nick Cave and sundry Bad Seeds, she has worked with Beck, PJ Harvey, Anna Calvi, the Clash’s Mick Jones, Lou Reed, Cat Power and Anohni. “I know,” she says. “I’m very lucky. I don’t know what it is, but it is there, and they are hipper, cooler and even more attractive.”

“She’s real,” suggests Warren Ellis. “She’s genuinely awesome, and she’s like a one-off. Everything you think she is, she is. She’s kind of unique in that she’s remained relevant; she hasn’t sort of slipped into some kind of nostalgia act. She’s very witty, she’s intelligent and she’s extraordinary, too, because she’s lived a life – she was like a trailblazer for so many people without even knowing it. There’s no kind of mould for her career. And whatever she tells you, it’s true: she shoots straight from the hip.”

Ellis says that She Walks in Beauty is the album Faithfull has “wanted to make all her life”. There’s a chance that it might also be her last: the after-effects of Covid on her lungs mean she is currently unable to sing. “And I may not be able to sing ever again,” she says. “Maybe that’s over. I would be incredibly upset if that was the case, but, on the other hand, I am 74. I don’t feel cursed and I don’t feel invincible. I just feel fucking human. But what I do believe in, which gives me hope, I do believe in miracles. You know, the doctor, this really nice National Health doctor, she came to see me and she told me that she didn’t think my lungs would ever recover. And where I finally ended up is: OK, maybe they won’t, but maybe, by a miracle, they will. I don’t know why I believe in miracles. I just do. Maybe I have to, the journey I’ve been on, the things that I’ve put myself through, that I’ve got through so far and I’m OK. Does that sound really corny?”

No, I say, I don’t think it sounds corny. It sounds hopeful. “Yes,” she says. “We must be hopeful – it’s really important. And I am, yes. I’m bloody still here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment