LONG READ

by Shwe Lu Maung | Published: 00:00, Mar 06,2021

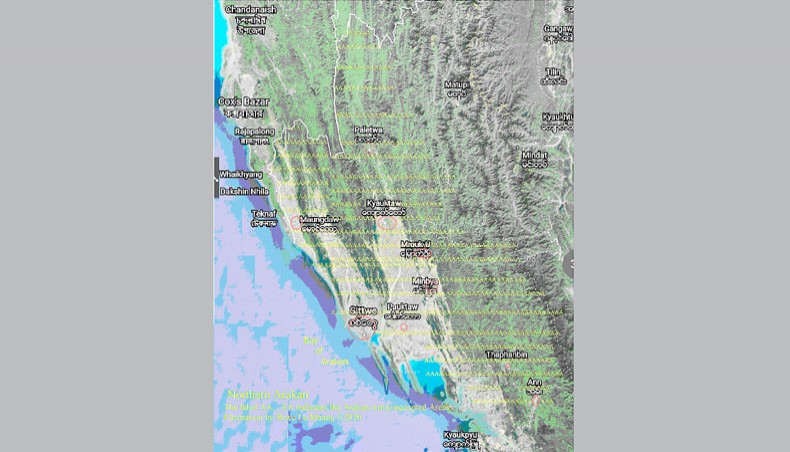

A map of northern Arakan shows the area occupied by the Arakan Army as of November 2020. The label AA indicates the Arakan Army-occupied areas.

THIS article is written to mark March 2, 1962, the day the Myanmar Armed Forces seized power and enslaved the peoples under the military colonialism. On that very night, a meeting of the Rangoon University Students Union was held. About 300 students attended the meeting. Some 50 of them pledged to oppose and fight the junta. I was one of them. Now, after 59 years, I am the only one surviving and talking. With this humble article, I honour my comrades who sacrificed their lives in our fight for freedom from the military colonialism. You can find the brief account of the student meeting in my book Burma: Nationalism and Ideology.

Déjà vu

ON THE 1st day of February 2021, there was a ‘coup’ in Myanmar, again! The military takeover in Burma, aka Myanmar, is nothing new. As a matter of fact, calling it a ‘coup’ is a misnomer because the Burmese military has been in power since 1962. It never left power. The Revolutionary Government of the Union Burma (1962–1974), the Socialist Government of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma (1974–1988), the State Law and Order Restoration Council (1988–1997), and the State Peace and Development Council (1977–2010) were the military governments. As per the 2008 constitution, the Myanmar military stays at the ‘backstage’ behind the curtain rather than at ‘frontstage’ in front of the curtain. Now, the Myanmar military comes out to the ‘frontstage.’ The word ‘coup,’ though, is catchy and easy to use, with a punch.

Suu Kyi’s dilemma

IN 2010, a general election was held as per the 2008 constitution, and the so-called ‘democracy transit’ took its first step. However, the very essence of the constitution is the military rule. The constitution itself was approved by a national referendum held at gunpoint by the SPDC. Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the National League for Democracy, boycotted the 2010 election. It did not accept the constitution and did not recognise the 2010 Naypyitaw government led by president Thein Sein, a former general and chair of the pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party.

However, Aung San Suu Kyi changed her mind in 2015, took part in, and won the election to form the Naypyitaw government. As such, Aung San Suu Kyi recognised the constitution-2008 and legitimised the military power in the Myanmar government. Aung San Suu Kyi voluntarily entered into the trap laid by the Myanmar military. This was her big mistake. She should have remained aloof from the party politics and power struggle. She should have let the National League for Democracy go into the power struggle while she remains as the ‘democracy icon’ opposing the 2008 constitution. After a momentary refusal, she accepted the ‘dinner invitation’ and then criticised the host for the ‘bad dinner.’ This is a bad policy.

Suu Kyi’s struggle for presidency

SUU KYI won the 2015 election with over 60 per cent majority in both houses of the parliament. After the win, her struggle was to revoke Section 59(f) of the 2008 constitution that makes Suu Kyi ineligible for the presidency due to her marriage to a foreigner so that she can be the president of the country. Her adviser Ko Ni, a lawyer by profession with specialisation in the constitutional laws and a Burmese Muslim of Indian ancestry, charted out the office of state counsellor. Suu Kyi took his advice and bypassed the president in her capacity as the state counsellor, becoming the de facto ruler. Ko Ni was assassinated in broad daylight at Rangoon Airport on Sunday, January 29, 2017. The mastermind of the assassination was a retired Lieutenant Colonel who vanished into the thin air, as per media reports.

Despite becoming the de facto ruler, her power remained limited due to the various constitutional provisions.

Constitutional game

THE most known part of the Myanmar Constitution-2008 is the Section 109 that gives the 25 per cent of the parliamentary seats to the military representatives at all levels from the state and regional to the union or central legislature. However, the key is that the Myanmar armed forces known as the Defence Services or Tatmadaw is a totally independent body and is not under the government. Although Section 342 says, ‘The President shall appoint the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services,’ the President is required to appoint the person ‘proposed and approved’ by the Tatmadaw-controlled ‘National Defence and Security Council.’ In short, Tatmadaw is a state within the state that controls the state.

The term ‘the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services’ appears 51 times in the constitution in contrast to only one time in the US constitution. The Myanmar president is not the commander in chief. The ministries of defence, home affairs, and border affairs are completely under Tatmadaw. The other ministries are under the president. Nevertheless, the catch is here. Under the ministry of home affairs is the general administrative department. No administrative or government business can be done without the knowledge and approval of the department in the entire Myanmar.

In order to be the real power holder, Suu Kyi wanted to bring the department under her command.

A technical move

AUNG San Suu Kyi successfully removed the general administrative department from the military-controlled ministry of home affairs to place it in the newly created Suu Kyi-controlled ministry of the office of the union government by a law adopted by the NLD-led union parliament in December 2018. The general administrative department, a copy of the British colonial public administration or Indian Civil Service, is the key of the Myanmar civil administrative machinery. Her success in bringing the department under her control was hailed as a major achievement of Suu Kyi’s democratisation.

In reality, it is hard to call it ‘democratisation’ because the department is a copy of the British colonial Indian Civil Service system of 1858, which was a child of the East Indian Company Act 1853. It was and still is not a civil service but a surveillance system. Therefore, the oppression and exploitation go on as usual. The most known example is the conviction of the two Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, for their 2018 exposure of the Myanmar military 2017 massacre of the Rohingya people at Inn Din village. Aung San Suu Kyi called the journalists ‘the traitors.’

The thought of the Myanmar military’s coming to the ‘frontstage’ was born when the general administrative department was revoked from the military-controlled ministry of home affairs and invoked in the Suu Kyi-controlled ministry of the office of the union government in 2018. As mentioned earlier, the general administrative department is a copy of the 19th century British colonial administration system. Without it, the Bama majority will not be able to rule the 134 non-Bama minorities. For example, the world witnessed the rise of the Arakan Army in the Rakhine State in 2018. All through from December 2018 to December 2020, the Myanmar military had to engage in deadly battles with serious losses. The question is: how the Arakan Army was able to field more than 5,000 well-trained fighters in Arakan while it was headquartered and trained in the Northern Kachin State? One explanation is that the Myanmar army was devoid of intelligence since the General administrative department was taken away from its hand in 2018. I believe it was just a sheer coincidence of the time in the rise of the Arakan Army and the transfer of the general administrative department. Nevertheless, it is highly probable that the general administrative department under Suu Kyi deprived the Myanmar military of the intelligence to a considerable extent in 2019 and 2020. The Myanmar military considers the department to be a crucial instrument in intelligence collection for ‘the non-disintegration of the Union, non-disintegration of National solidarity, and perpetuation of sovereignty’ as highlighted in the preamble of the 2008 constitution. Section 20(e) of the constitution says, ‘The Defence Services is mainly responsible for safeguarding the non-disintegration of the Union, the non-disintegration of National solidarity and the perpetuation of sovereignty.’ There it goes. The defence services is just doing its duty!

In bottom line, the general administrative department must be shredded and trashed. A brand new citizen-friendly, decentralised and transparent public service system to meet the need of the 21st century must be introduced.

The game of election

THE ‘changing hands’ of the general administrative department is a drastic change of the personnel of the pro-military to pro-Suu Kyi. Rigorously, Suu Kyi reshuffled the department with her people and prepared for the great 2020 election victory. In Myanmar, since the days of U Nu, the elections are ‘made’ by the ruling party through their faithful. Strictly speaking, in Myanmar, election fraud is a common feature though it is done using the various loopholes of the law. Bribes such as a government job, a promotion, a business license, a business loan, and intimidation such as arrest with the charges of insurgent-connection, sedition, and corruption are very common. Irregularities can hardly be seen on the election day. Suu Kyi government and her National League for Democracy party did the same ‘Myanmar customary election business.’ On the top of that the party was quite successful in changing the ‘demography,’ especially in the Chin, Kachin and Karen States, in its favour. In addition, the National League for Democracy-controlled election commission fully or partially cancelled the election in a number of ethnic constituencies, amounting to 15–20 parliamentary seats, in the Rakhine, Kachin, Shan, Karen, and Mon States, where the party was sure to lose.

The result was that the National League for Democracy won 315 of 440 or 71.5 per cent in the House of Representatives and 161 of 224 or 71.8 per cent of the House of Nationalities. This amount of majority is not large enough to change the constitution, which, though Sections 6(f), 109(b), and 141(b), enable the military participation in politics and allotment of 25 per cent of parliamentary seats to the military. Similarly, it is not good enough to change Section 59(f) that makes Suu Kyi ineligible for the presidency due to her marriage to a foreigner. It needs a 75 per cent majority and a national referendum to repeal these sections. Such a national referendum will never happen because the military will surely stop it for reasons of national security.

The 2020 election result is not the main cause of the military coming out to the ‘frontstage,’ but a convenient excuse. It is true, though, that Tatmadaw is deeply concerned of Suu Kyi’s ambition for the presidency. So, why wait until the moonless midnight?

Street protests

THROUGHOUT the 20th century, in no country, street protests changed the government.

The Myanmar new military government, known as the State Administrative Council, has made the prisons ready for the new prisoners by releasing nearly 24,000 old prisoners. It appears to be a well-calculated plan, and many protestors will end up in the jail for up to 20 years, and many may get killed on the streets and in detention. It is a story of heart-breaking anguish. I went through it in my days, and I ended up as a revolutionary in the armed insurrection. I am still carrying on the revolution, though unarmed, with a heavy cost on my scientific career.

The big question is to create a condition that will make Tatmadaw withdraw from the politics. This is a very big task. It needs a philosophy, a strategy, and the tactics as well as the techniques. A street protest is simply symptomatic and emotion-driven. It is largely without any philosophy, strategy and tactics. It has some techniques only.

In Myanmar, it was not successful in 1962, 1974, not even in the most famous 1988 protest. It will not be successful in 2021 either.

Ethnic politics

UNFORTUNATELY, the ethnic tension, that is Bama-non-Bama tension, grew in the days of Suu Kyi government. Serious human rights violations against the Rohingyas in the Rakhine, amounting to ethnic cleansing and genocide, occurred in 2017 under the watchful eyes of Suu Kyi, and she, regardless of the Nobel Peace Prize, defended Myanmar at the International Court of Justice in December 2019. The rise of the Arakan Army in the Rakhine State in 2018 and the serious battles with great loss to the Myanmar military is another significant failure of Suu Kyi. The ‘terrorist’ classification of the Arakan Army by the Suu Kyi government keeps the peace-talk impossible.

In 2015, Tatmadaw and Thein Sein government planned out a 7-point nationwide ceasefire agreement and invited the ethnic armed organisations to enter into the ceasefire agreement. The most significant part of the agreement is that the term ‘ethnic armed organisations’ is used and such conventional terms as ‘insurgents,’ ‘rebels,’ or ‘minorities’ are completely discarded. The agreement was signed by eight organisations, and the government and Tatmadaw at Naypyitaw on October 15, 2015 and with another two organisations on February 13, 2018, bringing to a total of 10 ethnic armed organisations into the agreement. The agreement was also signed by China, India, Japan, Thailand, the EU, and the United Nations, as the international witnesses.

There are 21 ethnic armed organisations in Myanmar. Among the remaining 11 organisations are the powerful groups like United Wa State Army, Kachin Independence Organisation/Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, and United League of Arakan/Arakan Army, five of which together make up a fighting force of 60,000 under the banner of the Northern Alliance.

When Suu Kyi came to power in 2015, she undermined the nationwide ceasefire agreement by initiating her own peace programme known as the Panglong-21, citing her father Aung San’s initiative of the 1947 Panglong Agreement that brought in the Chin, the Kachin, and the Shan into the Union of Burma. This action of hers visibly annoyed Tatmadaw. The result was that neither the nationwide ceasefire agreement nor the Panglong-21 made any progress in the last five years. The peace process was completely stalled. Only the cosmetic once-a-year celebrative meetings were held for publicity with no substance.

It is interesting to note that on December 9, 2020, Tatmadaw had an ‘informal’ meeting with the Arakan Army at Wa Self-Administered Zone’s capital, Panghsang, Northern Shan State, near the China border. They agreed to an ‘informal’ unconditional ceasefire as long as needed to reach a ‘formal’ agreement. To my amazement, the meeting was facilitated by a Japanese mediator and the United Wa State Army, a friend of China. When asked why the Tatmadaw talked with the terrorist organisation, Arakan Army, Tatmadaw replied that it never called ‘AA, terrorist,’ implying that the ‘terrorist’ designation is the job of Aung San Suu Kyi. The ‘informal’ ceasefire happened at a snap, much unexpected and much out of the way. I was totally puzzled.

Only when the coup took place on the February 1, 2021 the reason for the rush of the ceasefire with the Arakan Army was enlightened. Tatmadaw cannot afford a war while taking over power at Naypyitaw.

Soon after the coup or assuming the duty assigned by the Union president as per Section 413(b) of the 2008 constitution, the commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing formed the state administrative council consisting of 17 members, with him in the chair or chief administrator. Out of the 17 members, eight are from the military, and nine are civilians. All soldiers are ethnic Bama, but among the civilians, six are non-Bama, from the Chin, Kachin, Karen, Kaya, Rakhine, and Shan ethnicity. Except for one banker, the rest of the civilians are seasoned politicians with their own parties that compete with the National League for Democracy, Suu Kyi’s party. This is the first time in the history of Myanmar that the top state administrative body is constituted with the inclusion of the non-Bama ethnic peoples, who constitute up to 35 per cent of Myanmar’s population.

After the formation of the state administrative council, the new junta announced nine objectives in three categories: 1. Political affairs, 2. Economic affairs, and 3. Social affairs. Each category has three objectives. In the political affairs, the two top objectives are (a) formation of a federal union, and (b) establishment of peace through the nationwide ceasefire agreement. Obviously, Tatmadaw is making alliance with the non-Bama ethnic forces to counter Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Arakan Army

AS DESCRIBED earlier, the rise of the Arakan Army is phenomenal. It started with 15 youths in 2009, and in November 2018, it fielded some 1,000 fighters in the Northern Arakan, it increases to 3,000 in 2019 and to more than 5,000 in mid-2020. In March 2020, the Arakan Army wiped out one whole company of Tatmadaw airborne soldiers and captured some 40 men, including its commanding officer, a major. Only the heavy air raids saved the Tatmadaw field command headquarter. At present, in the Northern Arakan, Tatmadaw controls only the city municipal areas, which is only 20 per cent. That means the Arakan Army controls 80 per cent of the Northern Arakan or the Rakhine State. Bordered with Bangladesh and India, it creates a worrisome situation for Tatmadaw. In particular, the Arakan Army is making good progress in forging a friendship with the Arakan Muslims. History evidenced the rise of Arakan and Mrauk-U glory with the Buddhist-Muslim alliance from 1430 to 1784.

Tatmadaw believes that Aung San Suu Kyi, in the last five years of her being in power, had every opportunity to cooperate with Tatmadaw in the nationawide ceasefire agreement peace process to achieve the goal of a federal union, but Aung San Suu Kyi simply wasted her time with her struggle to become the president of the country. The weakening of the agreement peace process due to her launching of Panglong-21 excluding the ‘terrorist Arakan Army’ was a contributing factor to the rise of the Arakan Army. It also believes that Suu Kyi’s cancellation of the election in the ethnic areas where she was sure to lose, in particular in the Rakhine state, created a grave situation that can escalate the ongoing deadly armed conflict to an unmanageable level. In November 2020, with the guarantee of peace and smooth election, the Arakan Army and Tatmadaw both called for the Rakhine state cancelled elections to be held. Unfortunately, Suu Kyi and her election commission turned down the call. Also, in the same time, the Rakhine State Parliament, including the military representatives, unanimously presented an official request to the Suu Kyi government to repeal the terrorist designation of the Arakan Army in order to enable a ceasefire talk. Suu Kyi turned it down.

In the given situation, Tatmadaw made an ‘informal’ ceasefire with the Arakan Army and also set free the top Rakhine politician Dr Aye Maung and his young colleague historian-writer U Wai Hin Aung from the infamous InSein prison on February 15, just two weeks after the coup. The duo was arrested by the Suu Kyi government in January 1918 on the charges of high treason and connection to the ‘terrorist’ Arakan Army under the Penal Code Articles 122 and 505, and sentenced to 20-year imprisonment in March 2019. At present, the Rakhine State is peaceful and quiet, while Rangoon and Mandalay boil with the protests. The protests in the Kachin, Karen, and Shan areas are minimal while there are no protests in the Chin, Kaya, and Rakhine States.

The Arakan War is the major factor in the 2021 coup, just like the Shan factor was in the 1962 coup. In a short time in late 2020, the Arakan Army strength went up to about 10,000 with a combat force of more than 7,000. This is the main concern.

Military withdrawal from politics

Now and then, Tatmadaw had said that it would withdraw from politics when the ethnic armed conflict ends and no more internal danger to ‘the Union integrity, the national solidarity, and the sovereignty.’

Myanmar needs to create a condition that will make Tatmadaw withdraw from the politics. Tatmadaw came into politics with the 1962 coup d’état putting up a strong reasoning that the Union of Burma was at the brink of disintegration due to the ethnic tension. Since then, the army stays on in power. Section 20(e) of the 2008 constitution says, ‘The Defence Services is mainly responsible for safeguarding the non-disintegration of the Union, the non-disintegration of National solidarity and the perpetuation of sovereignty.’ On this ground, Tatmadaw again comes out to the ‘frontstage’ that we conveniently call a ‘coup.’

Tatmadaw put the blame on the politicians and the ethnic armed organisations for creating a condition that endangers the very existence of the Union of Myanmar. In response, the ethnic armed organisations have announced and promised that their fight is for a genuine federal union, nothing more, nothing less. In return, in 1990, Tatmadaw admitted that it was wrong to equate federalism with secessionism. Tatmadaw stops calling the ethnic armed organisations secessionists, separatists, insurgents, or rebels and honours them with a respectful nomenclature of ‘Ethnic Armed Organisations’. Tatmadaw, also in 1990, erased out the term ‘minorities’ and introduced ‘ethnic peoples’ or ‘Taiyinthar’ that was happily welcomed by the ethnic peoples. At that time, General Than Shwe told the nation that Tatmadaw knows the ethnic peoples more than anybody else because of the Tatmadaw’s long experience in the ethnic areas in the civil war. His wife, Daw Kyaing Kyaing, is a Pa-O. They have eight children, a large family in Myanmar. Then and again, Tatmadaw highlights that it is the Tatmadaw that initiated the peace process with the first peace-talk in 1964. The main objective of the present Tatmadaw-led state administrative council is to build a genuine federal union through the nationwide ceasefire agreement peace process.

What shall we do?

IN THE light of the above discussion on the core issue, although it does not cover many other important aspects of Myanmar life, it will be reasonable for us to help Myanmar achieve a federal union with genuine democracy through the nationwide ceasefire agreement peace process. It is especially so because Aung San Suu Kyi’s politics is filled with ‘personality cult,’ casting a shade on the post-Suu Kyi era. It is also a fact that under her rule Myanmar witnessed increased armed conflicts and atrocities, and poverty escalation in the ethnic areas. Without peace and adequate social-economic security in the ethnic areas, Myanmar’s ‘democracy transit’ is meaningless.

How to help

1. To accord international recognition of autonomy struggle of the Myanmar ethnic peoples and their armed organisations in accordance with (1) the promise of the UN Charter Preamble objective 2: ‘to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small,’ and (2) the UN Charter, Chapter 1, Article 1.2 ‘the principle of equal rights and self-determination.’

2. To hold a UN-sponsored all-inclusive peace conference with all openness and fairness to help the Myanmar peoples formulate a new peaceful and lasting peace and federation in accordance with the promise of the UN Charter Preamble objective 3: ‘To achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.’

Epilogue

MYANMAR is in crisis for more than 70 years. The world is wrong to lock it up in the conventional, outdated, and rotten dungeon of ‘domestic affairs.’ Jumping and shouting only when the fire flares up is sheer stupidity. The problem is not just a question of a power struggle between Tatmadaw and Aung San Suu Kyi or democracy and authoritarianism. It is a struggle of all Myanmar peoples ‘for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.’

Shew Lu Maung is a writer. He has written books on Myanmarism and issues relevant to the area

No comments:

Post a Comment