LONDON RECONNECTION

THE SECOND COMING OF HYDROGEN? LONDON’S HYDROGEN BUSES

By Long Branch Mike

JAN 2021

Despite impressive advances, bus battery technology is still not optimal – poor range, and reduced energy storage in cold weather. So to avoid putting all their clean energy buses in one basket, TfL has consistently been evaluating hydrogen fuel cell buses.

Long before the first official determination of pollution as the cause of death of a 9 year old London girl shone the spotlight on the impact of pollution on respiratory systems, London had been at the vanguard of advancing clean transport technologies.

Additionally, a recent series of troubling London air pollution reports, such as the levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and other toxic volatile organic chemicals (VOC), are shedding new light on the extent of inhaled toxins and carcinogens on the Capital’s streets. Diesel bus exhaust results in buildup of NOx (NO + NO2) inside bus terminals.

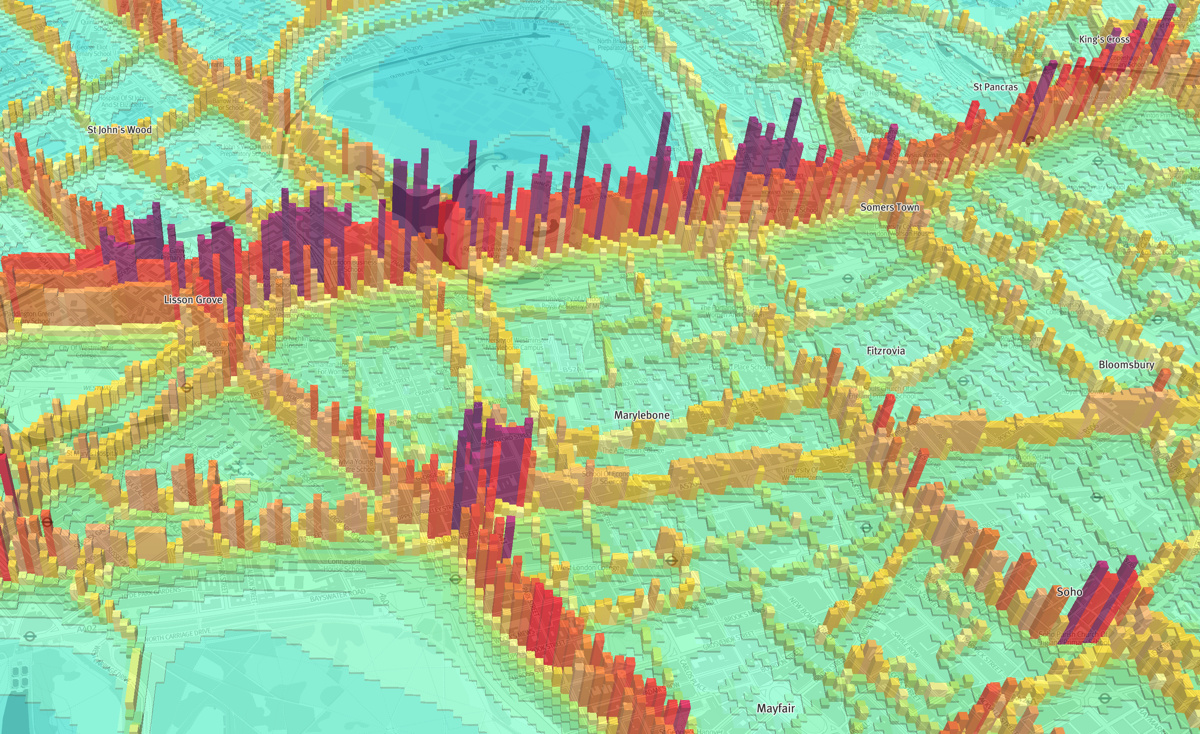

Modelled 2020 annual NO2 pollution levels in Marylebone. MappingLondon

The sudden reduction of cars, trucks, and buses in March 2020 due to the onset of the pandemic just as quickly resulted in clear skies over major cities worldwide. Unfortunately, traffic quickly returned, and the startling view of crystal clear air that shouldn’t be easily forgotten, has been forgotten. We note the recent realisation of the impact of brake and tyre particulates on air quality and breathing, but address only zero emission buses in this article.

The sudden reduction of cars, trucks, and buses in March 2020 due to the onset of the pandemic just as quickly resulted in clear skies over major cities worldwide. Unfortunately, traffic quickly returned, and the startling view of crystal clear air that shouldn’t be easily forgotten, has been forgotten. We note the recent realisation of the impact of brake and tyre particulates on air quality and breathing, but address only zero emission buses in this article.

TFL‘S ZERO EMISSION BUSES

To tackle the capital’s air quality crisis believed to be largely caused by diesel engines, recent Mayors and TfL had initiated a number of new clean air transport initiatives. We recently covered battery buses and ULEZ’s in On The Buses: Fares, Fumes and Finances, and now look at the role that hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) buses are starting to play.

We had first looked at London’s hydrogen buses in 2014 in Asphalt and Battery: The future of the London Bus (Part 2):

When you are responsible for a fleet of over eight thousand diesel buses it is only right and proper that you investigate alternative options and this TfL has done. At one stage hydrogen looked very promising. In the past few years TfL have experimented off and on with hydrogen buses on route RV1 but, whilst the latest buses are still in service, there does not seem to have been any effort made to extend them beyond this one route. This is probably because they are very expensive indeed. It is also the case that, although hydrogen can be seen as a solution for getting rid of tailpipe emission at the point of use, it does not solve any energy issues because more energy in the form of electricity is required to extract the hydrogen from water than can be obtained from burning it as a fuel (and creating water). As such, hydrogen is merely an alternative to the battery.

There are of course various other gases apart from hydrogen that can be burned. The problem with these are that they are still hydrocarbons but in gaseous rather than liquid form. The main attraction of these fuels for taxis and other vehicles is that they don’t attract fuel duty – something that bus operators don’t pay anyway.

Transport in London has had a long history of innovation, from the pioneering Metropolitan Line in 1863, the first electrically powered Underground line in 1890, to the world’s first automated underground line in 1968. Buses have not been exempt from technological advancement, with London at the forefront of bus technologies and designs such as the original Routemaster.

LONDON’S FIRST HYDROGEN BUS ROUTE – RV1

TfL’s first foray into hydrogen power started on Riverside bus route RV1 in 2002. The route connected Central London with South Bank attractions, including the Royal Festival Hall, National Theatre, London Eye, and Tate Modern, and operated between Covent Garden via Tower Gateway station, Waterloo, London Bridge station and Tower Bridge, serving many streets that previously had not been served by buses. The short 6 mile route length, dense central London routing and high visibility to tourists meant that RV1 was an ideal route to trial and fly the environmentally friendly bus flag – the only emissions of hydrogen vehicles being oxygen and water.

A hydrogen fuel cell bus on RV1

The hydrogen buses serving on this route were initially three hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) powered Mercedes-Benz Citaros operated between 2004 and 2010. Some of these buses were also trialled on route 25 in 2009. This small fleet allowed TfL to compare their efficiency directly against diesel powered Citaros. However, due to a lack of hydrogen capacity in those buses, their limited range only allowed operation in the mornings and early afternoon. Whilst the RV route prefix was part of Riverside branding, there was cynical speculation that it also meant Research Vehicle.

The hydrogen buses serving on this route were initially three hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) powered Mercedes-Benz Citaros operated between 2004 and 2010. Some of these buses were also trialled on route 25 in 2009. This small fleet allowed TfL to compare their efficiency directly against diesel powered Citaros. However, due to a lack of hydrogen capacity in those buses, their limited range only allowed operation in the mornings and early afternoon. Whilst the RV route prefix was part of Riverside branding, there was cynical speculation that it also meant Research Vehicle.

Mercedes-Benz Citaro in 2004. Walthamstow Writer

The Citaros were removed from RV1 service in 2010, replaced by eight new Wrightbus Pulsar 2 hydrogen-powered VDL SB200 bodied single-decker buses purchased by First London, which were operated on the route until 2013. Two Van Hool single decker hydrogen fuel cell A330FCs replaced the Alexander Dennis Enviro 200 Darts on route RV1 in January 2018, allowing a full hydrogen fleet to operate for the first time.

The Citaros were removed from RV1 service in 2010, replaced by eight new Wrightbus Pulsar 2 hydrogen-powered VDL SB200 bodied single-decker buses purchased by First London, which were operated on the route until 2013. Two Van Hool single decker hydrogen fuel cell A330FCs replaced the Alexander Dennis Enviro 200 Darts on route RV1 in January 2018, allowing a full hydrogen fleet to operate for the first time.

Hydrogen tanks atop RV1 bus at Tower Gateway

Some of the RV1 hydrogen buses have apparently had poor ride quality and high interior noise levels, equivalent to a diesel bus. As a comparison, battery electric buses are considered far superior in these respects.

Some of the RV1 hydrogen buses have apparently had poor ride quality and high interior noise levels, equivalent to a diesel bus. As a comparison, battery electric buses are considered far superior in these respects.

MASSIVE CUTBACK IN RV1 BUS FREQUENCY AFTER LONDON BRIDGE REBUILD

Part of route RV1’s continued raison d’être was the Thameslink Programme London Bridge rebuild. The biggest capacity gap it was helping to fill started to fall off post May 2016 (when the bus route ridership halved), then in August 2017 with the station works phasing changes. With the Blackfriars Southern entrance opening, combined with renewed peak Thameslink service from London Bridge, the 2019 RV1 ridership dropped to about 10% of what it once was.

It was thus no surprise that route RV1 was discontinued on 15 June 2019. Diesel bus route 343 was then extended from Aldgate to Tower Gateway to replace the service between London Bridge and Tower Gateway. The Wrightbus hydrogen single deckers were moved to route 444 and the Van Hools to storage.

To develop a dedicated hydrogen source, TfL are coordinating with Project Cavendish, a collaborative feasibility project between Southern Gas Networks (SGN), National Grid, and Cadent. This project is evaluating the potential of using the Isle of Grain’s existing infrastructure to supply hydrogen to London & the South East, including hydrogen generation by steam methane reforming (SMR), storage, and transport. Sixty kilometres east of London, the Isle of Grain hosts the National Grid’s Grain liquid natural gas (LNG) terminal, as well as a number of gas shipping terminals, gas blending facilities, and considerable natural gas storage.

SMR is the traditional hydrogen generation technology, also called ‘gray hydrogen’ for its dirty fossil fuel production method, which releases carbon into the atmosphere during processing. However, this process can be rectified with CO₂ capture, to a low-carbon standard to make ‘blue hydrogen’. This is the hydrogen that TfL is hoping to use.

NEXT GENERATION HYDROGEN BUSES

In 2018 London once again took a technological jump on transport innovation – TfL commissioned two hydrogen fuel cell double deckers – a world first. One is a conversion of a former hybrid bus demonstration vehicle, and the second is a brand new double decker Streetdeck FCEV (fuel cell electric vehicle), again from Wrightbus, powered by Ballard hydrogen fuel cells. They are due to be trialled by Tower Transit from Lea Interchange garage.

THE MAYOR’S IMPERATIVE

Mayor Sadiq Khan has made tackling the public health issues caused by air pollution one of his major initiatives. Toxic air is a threat to all Londoners’ health, especially children, the elderly, and those with lung and heart problems. Scientific studies are starting to show that high values of air pollutants correlate with more severe COVID symptoms.

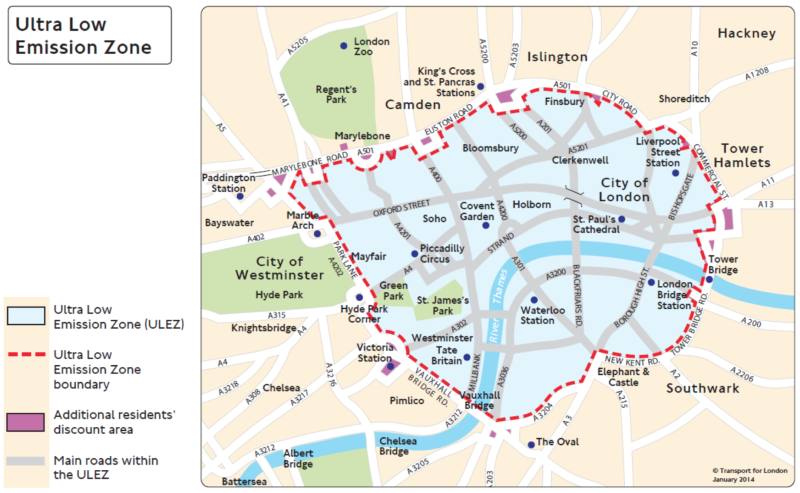

Under his initiative, the 2019 Mayoral Plan set the goal of 2,000 zero-emission London buses by 2025, and a full zero-emission bus fleet by 2037 at the latest. When TfL introduced the ten Low Emission Bus Zones and the world’s first Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) in April 2019, harmful nitrous oxides (NOx) emissions were reduced by 90% on some of the capital’s busiest roads in only a few months.

TfL then announced in May 2019 that it will introduce 20 of the new Wrightbus hydrogen buses into service in 2020 on London bus routes 245, 7 and N7. All of the buses in the ULEZ, and 75% of the entire bus fleet, already meet these standards. The plan was to have the entire TfL bus fleet meet the standards by October 2020, making the entire city a Low Emission Bus Zone. Unfortunately, one of responses to the coronavirus pandemic was to temporarily remove the ULEZ restrictions.

London ULEZ in 2014

TfL’s currently operates over 200 zero emission buses, Europe’s largest electric fleet, mostly battery powered. However, hydrogen buses can store more energy on board than equivalent battery buses, meaning they can be deployed on longer routes. Hydrogen buses now only need be refuelled for five minutes once a day, making them much quicker to refuel than to recharge battery buses.

In June 2020 Ryse, a hydrogen generation company, and Wrightbus, the manufacturer of London’s New Routemasters, won the 10-year contract to deliver these buses in 2020. Once the new Wrightbus hydrogen bus squadron is in service, London will have the largest zero-emission bus fleet in Europe. We know what you’re thinking – so hold that thought.

TfL’s currently operates over 200 zero emission buses, Europe’s largest electric fleet, mostly battery powered. However, hydrogen buses can store more energy on board than equivalent battery buses, meaning they can be deployed on longer routes. Hydrogen buses now only need be refuelled for five minutes once a day, making them much quicker to refuel than to recharge battery buses.

In June 2020 Ryse, a hydrogen generation company, and Wrightbus, the manufacturer of London’s New Routemasters, won the 10-year contract to deliver these buses in 2020. Once the new Wrightbus hydrogen bus squadron is in service, London will have the largest zero-emission bus fleet in Europe. We know what you’re thinking – so hold that thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment