UPDATED

Scientists create human-monkey hybrid embryos in a lab

YOU SAY CHYMERA, I SAY KYMERA,

LET'S CALL THE WHOLE THING OFF

Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe

Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe

By Mike Wehner @MikeWehner

April 15th, 2021

“Has science gone too far?” has become something of a meme of late. People post the question sarcastically on images of homemade Oreos with cream from 100 of the cookies, or a fast-food sandwich where the buns are replaced with fried chicken. It’s funny, but scientists are now legitimately asking the question after a team of researchers revealed that they have created chimera embryos in the lab.

A chimera is a hybrid of two species. In this case, scientists working on new possibilities for creating lab-grown organs for human transplants created early embryos that are half-human and half-monkey. The idea is that if scientists can grow parts of animals in the lab, and those pieces are close enough to humans to be used for transplants, a limitless supply of new organs could be on the horizon. The problem? They’re growing human/monkey hybrids in a lab for the purpose of slicing them up and sticking the pieces in living humans.

Scientists have experimented with using certain types of human stem cells in animal embryos in the past, including in pigs and mice. They found that the tissues were simply too different to allow for strong integration. Monkeys, on the other hand, are much more closely related to humans, and when using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) in cynomolgus monkey embryos in the lab, they found that the human cells integrated at a might deeper level.

Interspecies chimera formation with human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) represents a necessary alternative to evaluate hPSC pluripotency in vivo and might constitute a promising strategy for various regenerative medicine applications, including the generation of organs and tissues for transplantation.

So, scientists found a way to get human stem cells to play nicely with monkey embryos, but that’s not all. They also found that the cells communicated in a way that they didn’t necessarily expect. The findings suggest that there’s a lot to learn about the evolutionary paths of both humans and primates, and it may aid in the development of hybrids in the future, for better or worse.

We also uncovered signaling events underlying interspecific crosstalk that may help shape the unique developmental trajectories of human and monkey cells within chimeric embryos. These results may help to better understand early human development and primate evolution and develop strategies to improve human chimerism in evolutionarily distant species.

Ultimately we’re going to have to make a choice as a species. Are we okay with creating what are essentially organ farms, where we exploit nature (including other species) in order to grow organs for transplant into humans? Could it eventually save human lives? Almost certainly yes. But those lives will be saved after we create a new hybrid species, at least in part, and then kill and harvest its organs. Creepy.

Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe

Image source: Javier Duran/AdobeBy Mike Wehner @MikeWehner

April 15th, 2021

“Has science gone too far?” has become something of a meme of late. People post the question sarcastically on images of homemade Oreos with cream from 100 of the cookies, or a fast-food sandwich where the buns are replaced with fried chicken. It’s funny, but scientists are now legitimately asking the question after a team of researchers revealed that they have created chimera embryos in the lab.

A chimera is a hybrid of two species. In this case, scientists working on new possibilities for creating lab-grown organs for human transplants created early embryos that are half-human and half-monkey. The idea is that if scientists can grow parts of animals in the lab, and those pieces are close enough to humans to be used for transplants, a limitless supply of new organs could be on the horizon. The problem? They’re growing human/monkey hybrids in a lab for the purpose of slicing them up and sticking the pieces in living humans.

Scientists have experimented with using certain types of human stem cells in animal embryos in the past, including in pigs and mice. They found that the tissues were simply too different to allow for strong integration. Monkeys, on the other hand, are much more closely related to humans, and when using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) in cynomolgus monkey embryos in the lab, they found that the human cells integrated at a might deeper level.

Interspecies chimera formation with human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) represents a necessary alternative to evaluate hPSC pluripotency in vivo and might constitute a promising strategy for various regenerative medicine applications, including the generation of organs and tissues for transplantation.

So, scientists found a way to get human stem cells to play nicely with monkey embryos, but that’s not all. They also found that the cells communicated in a way that they didn’t necessarily expect. The findings suggest that there’s a lot to learn about the evolutionary paths of both humans and primates, and it may aid in the development of hybrids in the future, for better or worse.

We also uncovered signaling events underlying interspecific crosstalk that may help shape the unique developmental trajectories of human and monkey cells within chimeric embryos. These results may help to better understand early human development and primate evolution and develop strategies to improve human chimerism in evolutionarily distant species.

Ultimately we’re going to have to make a choice as a species. Are we okay with creating what are essentially organ farms, where we exploit nature (including other species) in order to grow organs for transplant into humans? Could it eventually save human lives? Almost certainly yes. But those lives will be saved after we create a new hybrid species, at least in part, and then kill and harvest its organs. Creepy.

Scientists grow human-monkey chimeric embryos in lab

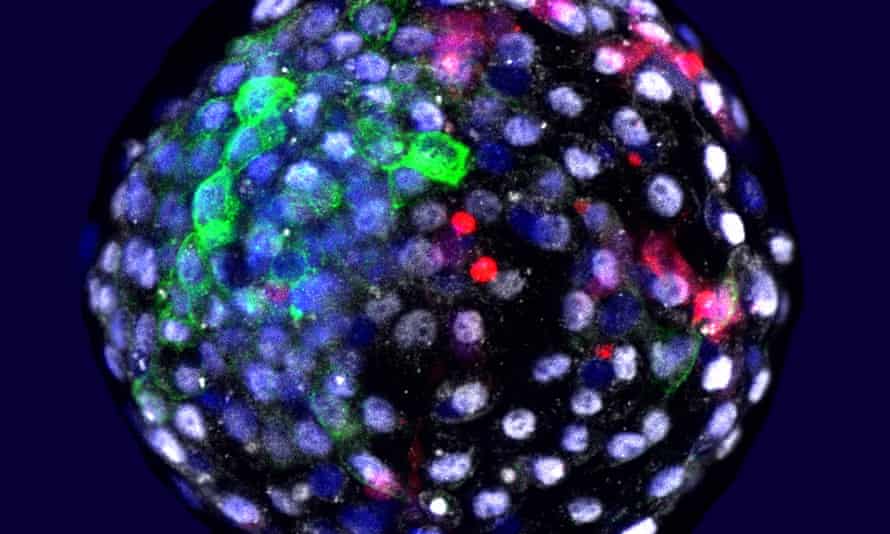

A closeup image shows a chimera human-monkey blastocyst, a proto-embryo tissue mass. Photo by Weizhi Ji/Kunming University of Science and Technology

April 15 (UPI) -- After injecting human stem cells into primate embryos, scientists were able to grow and maintain human-monkey chimeric embryos for up to 20 days.

The international research team, including geneticists in China and the United States, detailed their breakthrough in a new paper, published Thursday in the journal Cell.

Scientists suggest human-monkey chimeric embryos can be used to build models for studying human biology and disease.

"As we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans, it is essential that we have better models to more accurately study and understand human biology and disease," senior study author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, an expert in pluripotent stem cells who operates a lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California, said in a news release. "An important goal of experimental biology is the development of model systems that allow for the study of human diseases under in vivo conditions."

The research builds on previous successes achieved by Izpisua Belmonte and his research partners in China. The team first successfully created human-monkey chimeric embryos a few years ago, keeping them alive for only a few days.

For the most recent experiments, researchers injected monkey embryos with up to 25 extended pluripotent stem cells, stem cells with the potential to form both embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues.

After a day, scientists detected human cells in 132 embryos. After 10 days, 103 of the chimeric embryos were still growing. By Day 19, just three of chimeric embryos were still alive. Throughout the experiment, the viable chimeric embryos maintained large concentrations of human cells.

RELATED Researchers grow human cells in sheep embryos

"Historically, the generation of human-animal chimeras has suffered from low efficiency and integration of human cells into the host species," Izpisua Belmonte said. "Generation of a chimera between human and non-human primate, a species more closely related to humans along the evolutionary timeline than all previously used species, will allow us to gain better insight into whether there are evolutionarily imposed barriers to chimera generation and if there are any means by which we can overcome them."

Scientists observed the formation of new and strengthened communication pathways between human and monkey cells as the chimeric embryos grew.

"Understanding which pathways are involved in chimeric cell communication will allow us to possibly enhance this communication and increase the efficiency of chimerism in a host species that's more evolutionarily distant to humans," Izpisua Belmonte said

Moving forward, scientists plan to identify and study the interspecies communication pathways that are essential to the viability of chimeric embryos. Eventually, researchers hope to convert chimeric embryos into models for studying human biology and disease. In the future, chimeric embryos could also be used to grow transplantable cells, tissues or organs.

In an editorial accompanying the newly published paper, scientists said they built in safeguards to avoid ethical problems throughout their experiments. These include ethical consultations and reviews at the institutional level and with outside bioethicists

A closeup image shows a chimera human-monkey blastocyst, a proto-embryo tissue mass. Photo by Weizhi Ji/Kunming University of Science and Technology

April 15 (UPI) -- After injecting human stem cells into primate embryos, scientists were able to grow and maintain human-monkey chimeric embryos for up to 20 days.

The international research team, including geneticists in China and the United States, detailed their breakthrough in a new paper, published Thursday in the journal Cell.

Scientists suggest human-monkey chimeric embryos can be used to build models for studying human biology and disease.

"As we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans, it is essential that we have better models to more accurately study and understand human biology and disease," senior study author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, an expert in pluripotent stem cells who operates a lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California, said in a news release. "An important goal of experimental biology is the development of model systems that allow for the study of human diseases under in vivo conditions."

The research builds on previous successes achieved by Izpisua Belmonte and his research partners in China. The team first successfully created human-monkey chimeric embryos a few years ago, keeping them alive for only a few days.

For the most recent experiments, researchers injected monkey embryos with up to 25 extended pluripotent stem cells, stem cells with the potential to form both embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues.

After a day, scientists detected human cells in 132 embryos. After 10 days, 103 of the chimeric embryos were still growing. By Day 19, just three of chimeric embryos were still alive. Throughout the experiment, the viable chimeric embryos maintained large concentrations of human cells.

RELATED Researchers grow human cells in sheep embryos

"Historically, the generation of human-animal chimeras has suffered from low efficiency and integration of human cells into the host species," Izpisua Belmonte said. "Generation of a chimera between human and non-human primate, a species more closely related to humans along the evolutionary timeline than all previously used species, will allow us to gain better insight into whether there are evolutionarily imposed barriers to chimera generation and if there are any means by which we can overcome them."

Scientists observed the formation of new and strengthened communication pathways between human and monkey cells as the chimeric embryos grew.

"Understanding which pathways are involved in chimeric cell communication will allow us to possibly enhance this communication and increase the efficiency of chimerism in a host species that's more evolutionarily distant to humans," Izpisua Belmonte said

Moving forward, scientists plan to identify and study the interspecies communication pathways that are essential to the viability of chimeric embryos. Eventually, researchers hope to convert chimeric embryos into models for studying human biology and disease. In the future, chimeric embryos could also be used to grow transplantable cells, tissues or organs.

In an editorial accompanying the newly published paper, scientists said they built in safeguards to avoid ethical problems throughout their experiments. These include ethical consultations and reviews at the institutional level and with outside bioethicists

expert reaction to study looking at generating human-monkey chimeric embryos

A photo issued by the Salk Institute shows human cells grown in an early stage monkey embryo. Photograph: Weizhi Ji/Kunming University of Science and Technology/PA

Nicola Davis

Nicola Davis

Science correspondent

THE GUARDIAN

Thu 15 Apr 2021

Monkey embryos containing human cells have been produced in a laboratory, a study has confirmed, spurring fresh debate into the ethics of such experiments.

The embryos are known as chimeras, organisms whose cells come from two or more “individuals”, and in this case, different species: a long-tailed macaque and a human.

In recent years researchers have produced pig embryos and sheep embryos that contain human cells – research they say is important as it could one day allow them to grow human organs inside other animals, increasing the number of organs available for transplant.

Now scientists have confirmed they have produced macaque embryos that contain human cells, revealing the cells could survive and even multiply.

In addition, the researchers, led by Prof Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte from the Salk Institute in the US, said the results offer new insight into communications pathways between cells of different species: work that could help them with their efforts to make chimeras with species that are less closely related to our own.

“These results may help to better understand early human development and primate evolution and develop effective strategies to improve human chimerism in evolutionarily distant species,” the authors wrote.

The study confirms rumours reported in the Spanish newspaper El País in 2019 that a team of researchers led by Belmonte had produced monkey-human chimeras. The word chimera comes from a beast in Greek mythology that was said to be part lion, part goat and part snake.

The study, published in the journal Cell, reveals how the scientists took specific human foetal cells called fibroblasts and reprogrammed them to become stem cells. These were then introduced into 132 embryos of long-tailed macaques, six days after fertilisation.

“Twenty-five human cells were injected and on average we observed around 4% of human cells in the monkey epiblast,” said Dr Jun Wu, a co-author of the research now at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

The embryos were allowed to develop in petri dishes and were terminated 19 days after the stem cells were injected. In order to check whether the embryos contained human cells, the team engineered the human stem cells to produce a fluorescent protein.

Among other findings, the results reveal all 132 embryos contained human cells on day seven after fertilisation, although as they developed, the proportion containing human cells fell over time.

“We demonstrated that the human stem cells survived and generated additional cells, as would happen normally as primate embryos develop and form the layers of cells that eventually lead to all of an animal’s organs,” Belmonte said.

The team also reported that they found some differences in cell-cell interactions between human and monkey cells within chimeric embryos, compared with embryos of the monkeys without human cells.

Wu said they hoped the research would help develop “transplantable human tissues and organs in pigs to help overcome the shortages of donor organs worldwide”.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist from the Francis Crick Institute in London, said at the time of the El País report he was not concerned about the ethics of the experiment, noting the team had only produced a ball of cells. But he noted conundrums could arise in the future should the embryos be allowed to develop further.

While not the first attempt at making human-monkey chimeras – another group reported such experiments last year – the new study has reignited such concerns. Prof Julian Savulescu, the director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and co-director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities at the University of Oxford, said the research had opened a Pandora’s box to human-nonhuman chimeras.

“These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans,” he said, adding that a key ethical question is over the moral status of such creatures.

“Before any experiments are performed on live-born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed. What looks like a nonhuman animal may mentally be close to a human,” he said. “We will need new ways to understand animals, their mental lives and relationships before they are used for human benefit.”

Others raised concerns about the quality of the study. Dr Alfonso Martinez Arias, an affiliated lecturer in the department of genetics at the University of Cambridge, said: “I do not think that the conclusions are backed up by solid data. The results, in so far as they can be interpreted, show that these chimeras do not work and that all experimental animals are very sick.

“Importantly, there are many systems based on human embryonic stem cells to study human development that are ethically acceptable and in the end, we shall use this rather than chimeras of the kind suggested here.”

THE GUARDIAN

Thu 15 Apr 2021

Monkey embryos containing human cells have been produced in a laboratory, a study has confirmed, spurring fresh debate into the ethics of such experiments.

The embryos are known as chimeras, organisms whose cells come from two or more “individuals”, and in this case, different species: a long-tailed macaque and a human.

In recent years researchers have produced pig embryos and sheep embryos that contain human cells – research they say is important as it could one day allow them to grow human organs inside other animals, increasing the number of organs available for transplant.

Now scientists have confirmed they have produced macaque embryos that contain human cells, revealing the cells could survive and even multiply.

In addition, the researchers, led by Prof Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte from the Salk Institute in the US, said the results offer new insight into communications pathways between cells of different species: work that could help them with their efforts to make chimeras with species that are less closely related to our own.

“These results may help to better understand early human development and primate evolution and develop effective strategies to improve human chimerism in evolutionarily distant species,” the authors wrote.

The study confirms rumours reported in the Spanish newspaper El País in 2019 that a team of researchers led by Belmonte had produced monkey-human chimeras. The word chimera comes from a beast in Greek mythology that was said to be part lion, part goat and part snake.

The study, published in the journal Cell, reveals how the scientists took specific human foetal cells called fibroblasts and reprogrammed them to become stem cells. These were then introduced into 132 embryos of long-tailed macaques, six days after fertilisation.

“Twenty-five human cells were injected and on average we observed around 4% of human cells in the monkey epiblast,” said Dr Jun Wu, a co-author of the research now at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

The embryos were allowed to develop in petri dishes and were terminated 19 days after the stem cells were injected. In order to check whether the embryos contained human cells, the team engineered the human stem cells to produce a fluorescent protein.

Among other findings, the results reveal all 132 embryos contained human cells on day seven after fertilisation, although as they developed, the proportion containing human cells fell over time.

“We demonstrated that the human stem cells survived and generated additional cells, as would happen normally as primate embryos develop and form the layers of cells that eventually lead to all of an animal’s organs,” Belmonte said.

The team also reported that they found some differences in cell-cell interactions between human and monkey cells within chimeric embryos, compared with embryos of the monkeys without human cells.

Wu said they hoped the research would help develop “transplantable human tissues and organs in pigs to help overcome the shortages of donor organs worldwide”.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist from the Francis Crick Institute in London, said at the time of the El País report he was not concerned about the ethics of the experiment, noting the team had only produced a ball of cells. But he noted conundrums could arise in the future should the embryos be allowed to develop further.

While not the first attempt at making human-monkey chimeras – another group reported such experiments last year – the new study has reignited such concerns. Prof Julian Savulescu, the director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and co-director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities at the University of Oxford, said the research had opened a Pandora’s box to human-nonhuman chimeras.

“These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans,” he said, adding that a key ethical question is over the moral status of such creatures.

“Before any experiments are performed on live-born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed. What looks like a nonhuman animal may mentally be close to a human,” he said. “We will need new ways to understand animals, their mental lives and relationships before they are used for human benefit.”

Others raised concerns about the quality of the study. Dr Alfonso Martinez Arias, an affiliated lecturer in the department of genetics at the University of Cambridge, said: “I do not think that the conclusions are backed up by solid data. The results, in so far as they can be interpreted, show that these chimeras do not work and that all experimental animals are very sick.

“Importantly, there are many systems based on human embryonic stem cells to study human development that are ethically acceptable and in the end, we shall use this rather than chimeras of the kind suggested here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment