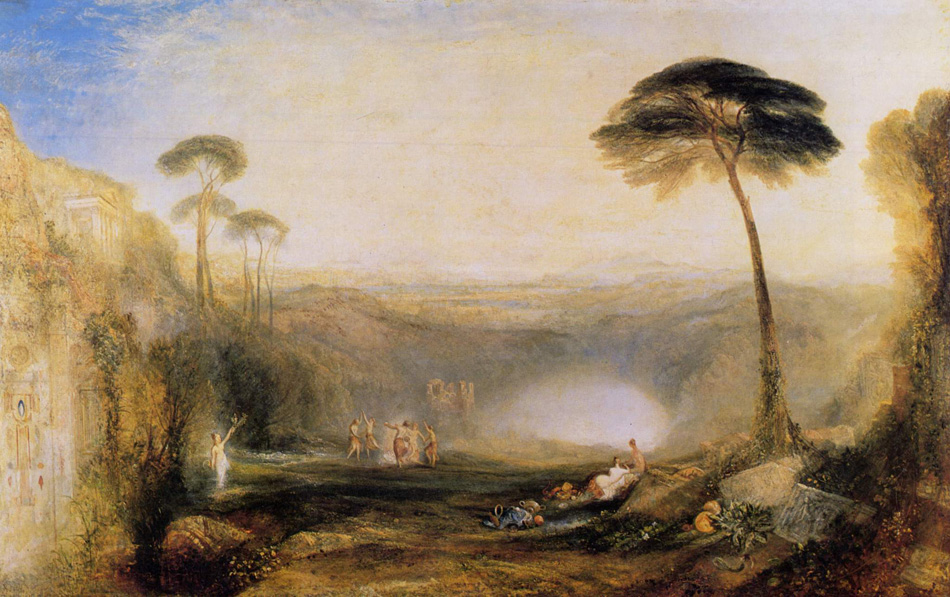

The Golden Bough, Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), Exhibited 1834. Medium Oil paint on canvas. Photo: © Tate, London 2014. This subject comes from Virgil’s poem, The Aeneid. The Trojan hero, Aeneas, has come to Cumae to consult the Sibyl, a prophetess. She tells him he can only enter the Underworld to meet the ghost of his father if he offers Proserpine a golden bough cut from a sacred tree. Turner shows the Sibyl holding a sickle and the freshly cut bough,in front of Lake Avernus, the legendary gateway to the Underworld. The dancing figures are the Fates. Like the snake in the foreground, they hint at death and the mysteries of the Underworld, amidst the beauty of the landscape.

Plant Folklore is a specialized, interdisciplinary field of study. Historical evidence indicates that humankind has sought to divine meaning from the natural world, often by explaining its origins through mythology and folktales. Advances in agriculture and horticulture had an obvious impact on human development, but to study the mythology of a plant in addition to its taxonomy, characteristics, and habitat can bring about enriched layers of understanding.

What is the human-plant connection?

Mutually dependent and beneficial (or toxic) relationships between plants and humans have existed for millennia. Economy, utility, and sustainability factor into human-horticultural application, but there are equal measures of superstition and tradition thrown into the mix. The study of plant lore is beneficial in stimulating our imaginations by seeking plant-human connections throughout history. The best discoveries are accidental.

Scottish social anthropologist Sir James George Frazer’s classic work, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, is an extraordinary work on the fundamentals of natural history. Labyrinthine and universal in scope, the Bough explores society’s relationship with its natural environment, and how cycles of nature are reflected in human ceremony and tradition. When you consider our current reliance upon technology, it’s easy to forget that our dependence upon nature used to be more pervasive, and at times even desperate.

Although not trained as a botanist, James G. Frazer (1854-1941) mounted this comprehensive study of human and natural history. Frazer devotes an entire chapter to the worship of trees, another to the influence of tree-spirits. We will explore these in a later installment. First, let’s consider the work and its general impact.

What does the title The Golden Bough refer to?

Frazer was inspired by Joseph Mallord William Turner‘s painting which depicts an episode from Virgil’s Aeneid: Having arrived at the gates of the underworld, the Trojan hero Aeneas seeks admittance to Hades so he may consult the spirit of his deceased father Anchises. The Sibyl (prophetess) of the adjoining lake instructs Aeneas how he may accomplish his task:

. . . Hidden in a dark tree

is a golden bough, golden in leaves and pliant stem,

sacred to Persephone, the underworld’s Juno, all the groves

shroud it, and shadows enclose the secret valleys.

But only one who’s taken a gold-leaved fruit from the tree

is allowed to enter earth’s hidden places.

This lovely Proserpine has commanded to be brought to her

as a gift: a second fruit of gold never fails to appear

when the first one’s picked, the twig’s leafed with the same metal.

So look for it up high, and when you’ve found it with your eyes,

take it, of right, in your hand: since, if the Fates have chosen you,

it will come away easily, freely of itself . . .Virgil’s Aeneid Book Six, “Aeneas Asks Entry to Hades”

Aeneas acts as instructed, and having picked the Golden Bough, presents it to Proserpine at the gates, is granted admittance to Hades, and ultimately finds his father who prophesizes the founding of Rome. Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, are direct descendants of Aeneas [family tree].

Frazer states that this part of The Aeneid took place at Lake Nemi, also called Diana’s Mirror, located just southeast of Rome [GPS]. However, according to the metadata hosted by The Tate Gallery London, Turner’s painting depicts the scene at Lake Avernus, closer to Naples [GPS]. (At least we’re still in Italy . . . )

The King of the Wood at Diana’s Mirror

Turner’s artwork compelled Frazer to uncover the origin of a curiously macabre, pagan ritual that took place at Lake Nemi. Its human-plant connection is apparent:

“In antiquity this sylvan landscape was the scene of a strange and recurring tragedy. On the northern shore of the lake . . . stood the sacred grove and sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis, or Diana of the Wood [fertility goddess of Classical Roman tradition] . . . . [in] this sacred grove there grew a certain tree round which at any time of day, and probably far into the night, a grim figure might be seen to prowl. In his hand he carried a drawn sword, and he kept peering warily about him as if at every instant he expected to be set upon by an enemy. He was a priest and a murderer; and the man for whom he looked was sooner or later to murder him and hold the priesthood in his stead. Such was the rule of the sanctuary. A candidate for the priesthood could only succeed to office by slaying the priest, and having slain him, he retained office till he was himself slain by a stronger or craftier . . . The post which he held by this precarious tenure carried with it the title of king [King of the Wood–Rex Nemorensis]; but surely no crowned head ever lay uneasier, or was visited by more evil dreams, than his.”James Frazier, “The King of the Wood,” The Golden Bough

Here is a parallel with Aeneas: the challenger of Diana’s priest was to pick a Golden Bough from that same sacred tree of the sanctuary. The ritual is said to have endured well into the Julio-Claudian dynasty (27 BC-68 AD) of Imperial Rome. The mad Emperor Caligula (12 AD-41 AD) even sent a “more stalwart ruffian” to slay the standing priest, whom he’d thought had overextended his devout tenure.

One cannot ignore the irony that a ritual of perpetual violence and temporality operated as an essential component to the worship of a fertility goddess. Why break off a tree branch and then confront a fight to the death? Was this meant to be an act of self-sacrifice combined with harming another human being? Who would want any part of this priesthood, if its destiny would result in an untimely death? What made that particular tree sacred to the worship of Diana? Why did the requisite challenger of the priest have to be a runaway slave? Frazer realized that he needed to go “farther afield” to trace the origins or even make sense of this ritual, and he ultimately concluded that the majority of old religions were fertility cults that practiced rituals involving the periodic worship and sacrifice of a sacred king. This sacrifice was crucial for a bountiful harvest—the deification/sacrifice of an individual for the common good. We may consider the universality of such religious beliefs.

In The Golden Bough, Frazer details the similarities of numerous world religions, in which death and rebirth are crucial elements of fecundity and survival. Consider the sheltering, recumbent winter followed by the recuperative spring. In a similar manner to religious rites, arts and literature may venerate nature.

The Bough’s Impact

Although greeted by considerable controversy by Victorian society (due in part to Frazer’s comparison of Jesus Christ with the sacred king sacrifice), this daring study of human ritual and its links to natural history influenced a new era of modern thought. Scientists (particularly anthropologists) and poets alike have found inspiration in this book. Indeed, his proposal that human belief developed directly from elemental magic to scientific method is a poignant and encouraging reminder of our own potential for inquiry and evolution.

Frazer published his first edition of The Golden Bough in two volumes (1890), expanded into three volumes for the second edition (1900), and finally a massive third edition issued in twelve volumes (1906-15). Various single-volume abridgements are the only editions currently in print. My favorite abridgment by far is the Oxford University Press edition, held by the Arnold Arboretum Library, because explanatory notes are contained in the margins of each section. I also recommend the Penguin Classics abridgement.

RESOURCES

The Golden Bough (complete) at the Internet Sacred Text Archive.

1890 edition online.

Audiobook (1894 edition).

—Larissa Glasser, Library Assistant

Plant Folklore is a specialized, interdisciplinary field of study. Historical evidence indicates that humankind has sought to divine meaning from the natural world, often by explaining its origins through mythology and folktales. Advances in agriculture and horticulture had an obvious impact on human development, but to study the mythology of a plant in addition to its taxonomy, characteristics, and habitat can bring about enriched layers of understanding.

What is the human-plant connection?

Mutually dependent and beneficial (or toxic) relationships between plants and humans have existed for millennia. Economy, utility, and sustainability factor into human-horticultural application, but there are equal measures of superstition and tradition thrown into the mix. The study of plant lore is beneficial in stimulating our imaginations by seeking plant-human connections throughout history. The best discoveries are accidental.

Scottish social anthropologist Sir James George Frazer’s classic work, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, is an extraordinary work on the fundamentals of natural history. Labyrinthine and universal in scope, the Bough explores society’s relationship with its natural environment, and how cycles of nature are reflected in human ceremony and tradition. When you consider our current reliance upon technology, it’s easy to forget that our dependence upon nature used to be more pervasive, and at times even desperate.

Although not trained as a botanist, James G. Frazer (1854-1941) mounted this comprehensive study of human and natural history. Frazer devotes an entire chapter to the worship of trees, another to the influence of tree-spirits. We will explore these in a later installment. First, let’s consider the work and its general impact.

What does the title The Golden Bough refer to?

Frazer was inspired by Joseph Mallord William Turner‘s painting which depicts an episode from Virgil’s Aeneid: Having arrived at the gates of the underworld, the Trojan hero Aeneas seeks admittance to Hades so he may consult the spirit of his deceased father Anchises. The Sibyl (prophetess) of the adjoining lake instructs Aeneas how he may accomplish his task:

. . . Hidden in a dark tree

is a golden bough, golden in leaves and pliant stem,

sacred to Persephone, the underworld’s Juno, all the groves

shroud it, and shadows enclose the secret valleys.

But only one who’s taken a gold-leaved fruit from the tree

is allowed to enter earth’s hidden places.

This lovely Proserpine has commanded to be brought to her

as a gift: a second fruit of gold never fails to appear

when the first one’s picked, the twig’s leafed with the same metal.

So look for it up high, and when you’ve found it with your eyes,

take it, of right, in your hand: since, if the Fates have chosen you,

it will come away easily, freely of itself . . .Virgil’s Aeneid Book Six, “Aeneas Asks Entry to Hades”

Aeneas acts as instructed, and having picked the Golden Bough, presents it to Proserpine at the gates, is granted admittance to Hades, and ultimately finds his father who prophesizes the founding of Rome. Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, are direct descendants of Aeneas [family tree].

Frazer states that this part of The Aeneid took place at Lake Nemi, also called Diana’s Mirror, located just southeast of Rome [GPS]. However, according to the metadata hosted by The Tate Gallery London, Turner’s painting depicts the scene at Lake Avernus, closer to Naples [GPS]. (At least we’re still in Italy . . . )

The King of the Wood at Diana’s Mirror

Turner’s artwork compelled Frazer to uncover the origin of a curiously macabre, pagan ritual that took place at Lake Nemi. Its human-plant connection is apparent:

“In antiquity this sylvan landscape was the scene of a strange and recurring tragedy. On the northern shore of the lake . . . stood the sacred grove and sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis, or Diana of the Wood [fertility goddess of Classical Roman tradition] . . . . [in] this sacred grove there grew a certain tree round which at any time of day, and probably far into the night, a grim figure might be seen to prowl. In his hand he carried a drawn sword, and he kept peering warily about him as if at every instant he expected to be set upon by an enemy. He was a priest and a murderer; and the man for whom he looked was sooner or later to murder him and hold the priesthood in his stead. Such was the rule of the sanctuary. A candidate for the priesthood could only succeed to office by slaying the priest, and having slain him, he retained office till he was himself slain by a stronger or craftier . . . The post which he held by this precarious tenure carried with it the title of king [King of the Wood–Rex Nemorensis]; but surely no crowned head ever lay uneasier, or was visited by more evil dreams, than his.”James Frazier, “The King of the Wood,” The Golden Bough

Here is a parallel with Aeneas: the challenger of Diana’s priest was to pick a Golden Bough from that same sacred tree of the sanctuary. The ritual is said to have endured well into the Julio-Claudian dynasty (27 BC-68 AD) of Imperial Rome. The mad Emperor Caligula (12 AD-41 AD) even sent a “more stalwart ruffian” to slay the standing priest, whom he’d thought had overextended his devout tenure.

One cannot ignore the irony that a ritual of perpetual violence and temporality operated as an essential component to the worship of a fertility goddess. Why break off a tree branch and then confront a fight to the death? Was this meant to be an act of self-sacrifice combined with harming another human being? Who would want any part of this priesthood, if its destiny would result in an untimely death? What made that particular tree sacred to the worship of Diana? Why did the requisite challenger of the priest have to be a runaway slave? Frazer realized that he needed to go “farther afield” to trace the origins or even make sense of this ritual, and he ultimately concluded that the majority of old religions were fertility cults that practiced rituals involving the periodic worship and sacrifice of a sacred king. This sacrifice was crucial for a bountiful harvest—the deification/sacrifice of an individual for the common good. We may consider the universality of such religious beliefs.

In The Golden Bough, Frazer details the similarities of numerous world religions, in which death and rebirth are crucial elements of fecundity and survival. Consider the sheltering, recumbent winter followed by the recuperative spring. In a similar manner to religious rites, arts and literature may venerate nature.

The Golden Bough book cover

The Bough’s Impact

Although greeted by considerable controversy by Victorian society (due in part to Frazer’s comparison of Jesus Christ with the sacred king sacrifice), this daring study of human ritual and its links to natural history influenced a new era of modern thought. Scientists (particularly anthropologists) and poets alike have found inspiration in this book. Indeed, his proposal that human belief developed directly from elemental magic to scientific method is a poignant and encouraging reminder of our own potential for inquiry and evolution.

Frazer published his first edition of The Golden Bough in two volumes (1890), expanded into three volumes for the second edition (1900), and finally a massive third edition issued in twelve volumes (1906-15). Various single-volume abridgements are the only editions currently in print. My favorite abridgment by far is the Oxford University Press edition, held by the Arnold Arboretum Library, because explanatory notes are contained in the margins of each section. I also recommend the Penguin Classics abridgement.

RESOURCES

The Golden Bough (complete) at the Internet Sacred Text Archive.

1890 edition online.

Audiobook (1894 edition).

—Larissa Glasser, Library Assistant

Aug 18, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment