A TRIBUTE

Revisiting ‘One Man’s Justice,’ the memoir of fighting for the vulnerable written by the renowned BC jurist two decades before his passing.

Ian Gill 5 May 2021 | TheTyee.ca

Ian Gill is co-owner of Vancouver bookstore Upstart & Crow, a co-creator of Salmon Nation and a contributing editor of The Tyee.

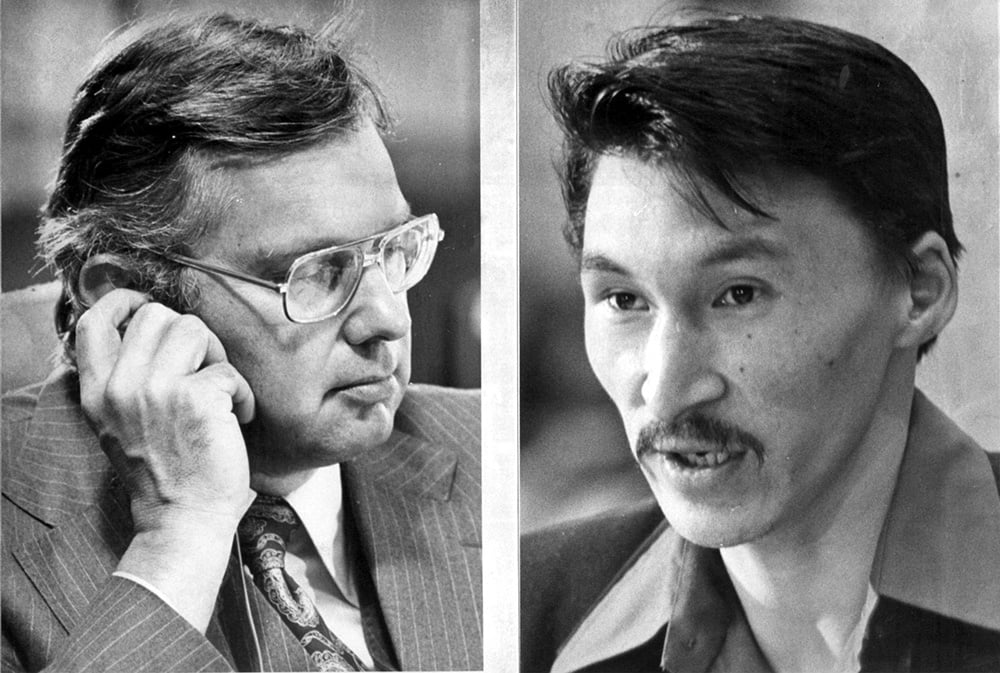

Justice Thomas Berger listens as John Amagoalik, director of land claims for the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada, speaks to the Berger Commission in Ottawa on June 3, 1976. Photo by Fred Chartrand, the Canadian Press picture archive.

Al ot has been written in a very short time recently about the long and storied life of Thomas Rodney Berger, who died last week aged 88. The obituaries of one of the finest jurists this country has ever produced have chronicled a lot of important commissions and headline grabbing cases he led, and rightly so. But they have almost universally failed to reference his personal traits.

Al ot has been written in a very short time recently about the long and storied life of Thomas Rodney Berger, who died last week aged 88. The obituaries of one of the finest jurists this country has ever produced have chronicled a lot of important commissions and headline grabbing cases he led, and rightly so. But they have almost universally failed to reference his personal traits.

I didn’t know Berger the Younger. He was called to the British Columbia bar in 1957, when I was barely out of nappies, as we called them in my native Australia. But I did get to know him a little starting in the ’90s. I was lucky enough to recruit him for a time to the board of Ecotrust Canada, and otherwise to see him occasionally over the years at various events, and the occasional lunch.

He was, in a word, avuncular. He had a polished, barrister’s baritone, an easy but authoritative way of speaking, ear cocked out of genuine curiosity, a smile never far away. For a big man with a sharp mind, there was a languidness about him that seemed to verge at times on diffidence. In fact, he was a master of soft power.

In his brilliant but incomplete memoir, One Man’s Justice: A Life in the Law, Berger writes that in high school he decided he wanted to be a teacher, a lawyer or a journalist. “All of those professions have one thing in common — they involve using language; they involve communicating ideas, speaking and writing. I’ve tried other things, but I’ve always returned to law.”

And thank goodness for that. The country, the world, is a better place because Tom Berger took an interest in justice and, in a statement last week from B.C. Premier John Horgan, “that meant he needed to address injustice.”

It was journeyman stuff to start out — small claims, administrative tribunals, criminal courts, “defending drug addicts, traffickers, thieves, burglars and prostitutes.” When he opened his own practice in 1963, his first client was a man charged with impaired driving. There was only one chair in his office. “Where was the client to sit? Where was I to sit? I couldn’t ask him to stand while I remained seated. On the other hand, it would seem peculiar if I remained on my feet throughout. I decided to move the chair to the other side of the desk, then I invited my client to sit down while I sat companionably on the corner of the desk, my hands folded in my lap, in an attitude of confidentiality. Perhaps he didn’t notice the absence of furniture.”

That was Berger to a T — the kind consideration of the other, the putting at ease of people at their uneasiest — i.e. people, often from the wrong side of the tracks, who found themselves on the wrong side of a system that seemed purpose-built to intimidate. All the more serendipitous that Berger in the 1960s started arguing Aboriginal rights cases. Thus, from a “a pocket-sized office,” he wrote, “the land claims industry developed.”

The defining Aboriginal rights case not just for Berger, but for Canada, was of course Calder vs. British Columbia, which took Berger and the Nisg̱a’a Nation to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1971, which upheld the place of Aboriginal rights in Canadian law.

“Tom filed the writ in the B.C. Supreme Court in 1969,” lawyer Don Rosenbloom told the Vancouver Sun last week. “It alleged that Aboriginal title had never been extinguished, and the First Nations maintained their ownership of the land.

“Lawyers in this city were just laughing, it was just, ‘Give me a break.’ They couldn’t believe a case was being taken that made such a suggestion. But it turned out not to be a joke. And look where we are today.”

Berger: “It helped that I was young and tireless and not fully aware of the obstacles that had to be surmounted.”

WATCH: Tom Berger discusses the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry he led. It proved a milestone for the assertion of Indigenous rights in Canada.

In 1971, at the age of 38, Berger was appointed to the B.C. Supreme Court, serving 12 years as a trial judge and three-time royal commissioner, one commission being the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry that “made me famous in Canada for a time.” So too his public dissent in 1983 against Canada’s adoption of a Constitution and Charter of Rights that abandoned provisions that recognized the rights of Indigenous, Inuit and Métis people. He left the bench and returned to practising law. You could say he never looked back.

But, thankfully, he did look back — in One Man’s Justice: A Life in the Law, written at the urging of Scott McIntyre and published by Douglas & McIntyre in 2002. (McIntyre also served on the Ecotrust Canada board. They were good times.)

It is out of print now (my partner and I are working on sourcing a few copies for the curious; see below), but One Man’s Justice remains one of my all-time favourite books. It is notable not just for its clear writing (Tom would have made a great journalist, although what a waste!), but for its description of cases — not all of them judicial triumphs — and characters who seemed unfavoured by society and thus the law.

People like Penny McNeil, the first woman in Canada to be prosecuted as a habitual criminal, a case “as sad as any I’ve ever done.” Declaring someone a habitual criminal meant they could be locked up for good, but in McNeil’s lifetime of prostitution and drug use she had never endangered another’s life, or property. “Her crimes were truly crimes against herself.”

Berger offers an empathetic description of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside — not just the blight, but the camaraderie and sense of community — that is as true now as it was then. McNeil and two other women Berger defended would be declared habitual criminals because the evidence showed they were, but in each instance they escaped preventive detention because their lawyer persuaded a judge that “the idea of imprisonment as a deterrent had virtually no effect on their conduct.” Legislation allowing people to be declared habitual criminals was repealed in 1977.

Dr. Jerilynn Prior was born in Alaska but moved to Canada in 1976 because she was opposed to American war-mongering in Vietnam and admired Canada’s universal health-care system. She was a Quaker who opposed the use of force and thus, by definition, the spending of her taxes by her government on military purposes. “How important is a conscience in a citizen’s life?” Berger asked. “Dr. Prior wished to apply the idea of conscientious objection to her taxes.”

Prior’s objections to her tax assessments had been heard and rejected in several Federal Court rulings and an appeal hung on whether there was a sufficient nexus between taxes and actual military expenditures to have violated Prior’s freedom of conscience. Berger failed to convince the Federal Court of Appeal to even hear Prior’s evidence and the Supreme Court of Canada turned down leave to appeal. “We were thrown off the bus at the first turn.” But Berger’s wide-ranging chapter on citizen conscience still stands up, especially these days when taxpayers should have every right to challenge our government’s war on nature, and its use of our money to subsidize the fossil fuel industry, for one; and fish farms, for another; and war machines, still.

MKULTRA, CIA AND DR. EWEN CAMERON

Linda Macdonald had been a victim of brainwashing experiments by Dr. Ewen Cameron at Montreal’s Allan Memorial Institute, funded by the American Central Intelligence Agency and later by the Canadian government. By the time Macdonald sought out Berger in 1988 the horror stories of wiping peoples’ memories through methods of gross medical malpractice had been widely told. Macdonald had been admitted to the AMI in 1963 for postpartum depression, then “treated” for schizophrenia, despite there being no evidence she suffered from it. After four months of more than 100 electroconvulsive shocks, untested combinations of barbiturates, anti-psychotic drugs and an 86-day drug induced sleep, she was discharged. “She had regressed to a child-like state. She had to be toilet trained. She could no longer read or write. She did not know her husband or children.”

At 26-years-old, Macdonald had been “depatterned” and then abandoned. Her legal issue was that Canada refused any culpability for what happened to her. In the end, it was her character and tenacity, rather than the courts, that determined the outcome: compensation for her, and other victims, although no admission of liability. Just a government crawling down in the face of a media storm that Berger realized was more powerful, and more speedily rendered, that any court decision could have been.

Linda Macdonald had been a victim of brainwashing experiments by Dr. Ewen Cameron at Montreal’s Allan Memorial Institute, funded by the American Central Intelligence Agency and later by the Canadian government. By the time Macdonald sought out Berger in 1988 the horror stories of wiping peoples’ memories through methods of gross medical malpractice had been widely told. Macdonald had been admitted to the AMI in 1963 for postpartum depression, then “treated” for schizophrenia, despite there being no evidence she suffered from it. After four months of more than 100 electroconvulsive shocks, untested combinations of barbiturates, anti-psychotic drugs and an 86-day drug induced sleep, she was discharged. “She had regressed to a child-like state. She had to be toilet trained. She could no longer read or write. She did not know her husband or children.”

At 26-years-old, Macdonald had been “depatterned” and then abandoned. Her legal issue was that Canada refused any culpability for what happened to her. In the end, it was her character and tenacity, rather than the courts, that determined the outcome: compensation for her, and other victims, although no admission of liability. Just a government crawling down in the face of a media storm that Berger realized was more powerful, and more speedily rendered, that any court decision could have been.

Thomas Berger receiving an honorary doctorate of laws from Vancouver Island University in 2013, one of 20 honorary degrees conferred upon him during his lifetime.

I mentioned that Berger’s memoir is incomplete and that’s true. It was published almost two decades before his death, and even into his eighth and ninth decades, an older and vastly wiser Tom Berger was still exhibiting his legendary stamina when tasked with making a good argument on a matter of principle.

He fought and won a battle to stop the Yukon government from undoing protections for the Peel Watershed, a vast expanse of sub-Arctic wilderness, after previously agreeing not to develop 80 per cent of it with the agreement of First Nations. He fought and won the Manitoba Métis Federation’s case that the government had defrauded Métis children out of 1.4 million acres of land. He fought and won a huge judgement against Imperial Tobacco on behalf of the B.C. government. All chapters that would have made it into a second edition, if only there’d been time. (Two excellent sources on his life are here and here.)

Kinder Morgan and Lessons from the Berger Inquiry

I mentioned that Berger’s memoir is incomplete and that’s true. It was published almost two decades before his death, and even into his eighth and ninth decades, an older and vastly wiser Tom Berger was still exhibiting his legendary stamina when tasked with making a good argument on a matter of principle.

He fought and won a battle to stop the Yukon government from undoing protections for the Peel Watershed, a vast expanse of sub-Arctic wilderness, after previously agreeing not to develop 80 per cent of it with the agreement of First Nations. He fought and won the Manitoba Métis Federation’s case that the government had defrauded Métis children out of 1.4 million acres of land. He fought and won a huge judgement against Imperial Tobacco on behalf of the B.C. government. All chapters that would have made it into a second edition, if only there’d been time. (Two excellent sources on his life are here and here.)

Kinder Morgan and Lessons from the Berger Inquiry

READ MORE

In December last year, in failing health, he argued before the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal that the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation is owed a “fair share” of compensation for lands flooded by SaskPower, an act that the Cree claim is a trespass on their reserve. “Berger expects to hear the top court’s decision sometime in 2021,” the Saskatoon StarPhoenix reported at the time.

Berger would love to have won that one (he might yet do so), because as warm and good-natured as he often appeared, he did like to win. “We are all of us animated by a mixture of motives,” he wrote in One Man’s Justice. “I acknowledge that ambition has played a part in my career.” That, and faith. “I’ve never become jaded — weary, dispirited, furious, frustrated perhaps, but I’ve never lost my faith in the law.”

Vale Thomas Rodney Berger.

Teacher. Lawyer. Author (not journalist).

1933-2021.

‘One Man’s Justice’ is out of print but Upstart & Crow is sourcing a small number of copies. Please email them if you would like to order a copy.

In December last year, in failing health, he argued before the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal that the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation is owed a “fair share” of compensation for lands flooded by SaskPower, an act that the Cree claim is a trespass on their reserve. “Berger expects to hear the top court’s decision sometime in 2021,” the Saskatoon StarPhoenix reported at the time.

Berger would love to have won that one (he might yet do so), because as warm and good-natured as he often appeared, he did like to win. “We are all of us animated by a mixture of motives,” he wrote in One Man’s Justice. “I acknowledge that ambition has played a part in my career.” That, and faith. “I’ve never become jaded — weary, dispirited, furious, frustrated perhaps, but I’ve never lost my faith in the law.”

Vale Thomas Rodney Berger.

Teacher. Lawyer. Author (not journalist).

1933-2021.

‘One Man’s Justice’ is out of print but Upstart & Crow is sourcing a small number of copies. Please email them if you would like to order a copy.

No comments:

Post a Comment