By Ross Pomeroy

June 29, 2021

Nestled near the top of a gentle sloping hill in the Southeastern Anatolia region of Turkey, surrounded by picturesque views of coarse, grassy savannah stretching into the distant horizon, rests the ruins of an ancient site dated to between 9,400 and 11,000 years ago. This is Göbekli Tepe. Though its dilapidated stones and worn-down pillars might hint at humble, solemn uses, archaeological examinations over the past decade have revealed a more convivial truth: Göbekli Tepe may have hosted some truly epic parties.

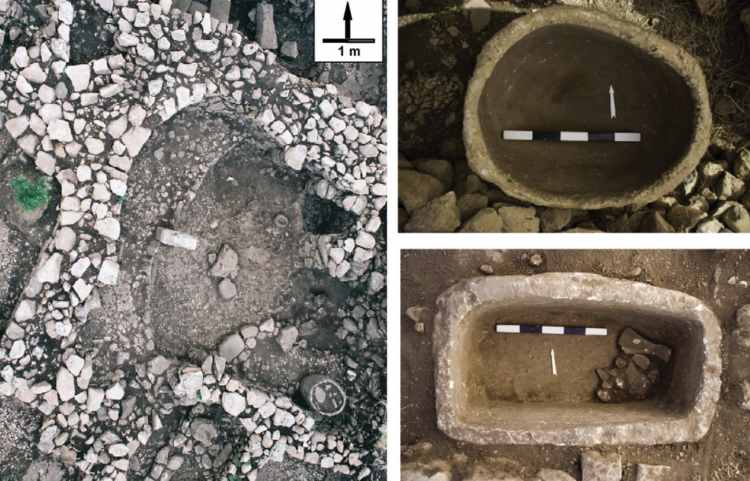

Southern Anatolia is at the northern end of the Fertile Crescent, a region in the Middle East invigorated by the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, where hunter-gatherers first settled down to farm. Göbekli Tepe was constructed sometime during this lifestyle transition, perhaps by different groups lured together through innate social desires. Exquisite carvings, decorated pillars, and animal-like figurines first suggested to researchers that this was a temple of some sort, intended for worship. Then, in 2012, archaeologists uncovered six large limestone troughs that could have each held up to 42 gallons of liquid. At the bottom of these structures were faint traces of oxalate, a compound which develops during the mashing and fermentation of cereals. To the researchers, this new evidence suggested that site's previously modest narrative needed a rewrite.

Limestone vessels likely used for brewing beer.

K. Schmidt, N. Becker, DAI

"At the dawn of the Neolithic, hunter-gatherers congregating at Göbekli Tepe created social and ideological cohesion through the carving of decorated pillars, dancing, feasting—and, almost certainly, the drinking of beer made from fermented wild crops," they wrote.

Whatever "worship" was going on at Göbekli Tepe, it was lively, to say the least.

Subsequent finds have reinforced this tale. In 2019, archaeologists examined more than 7,000 artifacts from the site. They described grinding tools that would have been used to process grains, as well as pieces of decorated stone drinking vessels. Absent from the area were any sort of storage facilities, suggesting that people didn't live at Göbekli Tepe, they just ate, drank, and partied there.

"Our findings... suggest that such feasts were held strategically in seasons favorable to the natural availability of plant food and meat between midsummer and autumn," they wrote.

Even more intriguing, the researchers found several miniature stone masks, suggesting that attendees may have masqueraded.

"We assume that the stone masks are miniature representations of real organic masks actually worn."

The festivals may have occasionally involved more 'freaky' activities, if a 2017 study is any indication. Scientists with the German Archaeological Institute detailed three modified skulls found at Göbekli Tepe.

"These skulls... attest to the special postmortem treatment of certain individuals at Göbekli Tepe. Special status of the individuals could have been emphasized through the application of decorative elements to the crania, which were then displayed at designated points around the site. At present, it is unknown whether these treatments were performed in the frame of ritual activities in the monumental buildings or were brought to the ritual center from settlement sites," they said.

Between boozy beer, tasty food, ornamented skulls, sculpted figures, incredible views, and great company, Neolithic parties at Göbekli Tepe more than 10,000 years ago must've been exciting spectacles. It may have been events like this that helped convince wide-ranging hunter-gatherer groups to settle down into more permanent villages. That way, they could party every night!

No comments:

Post a Comment