The Meat Industry’s Bestiality Problem

Big Agriculture’s artificial insemination is abusive. Most states have rewritten old laws to absolve it—but some haven’t.

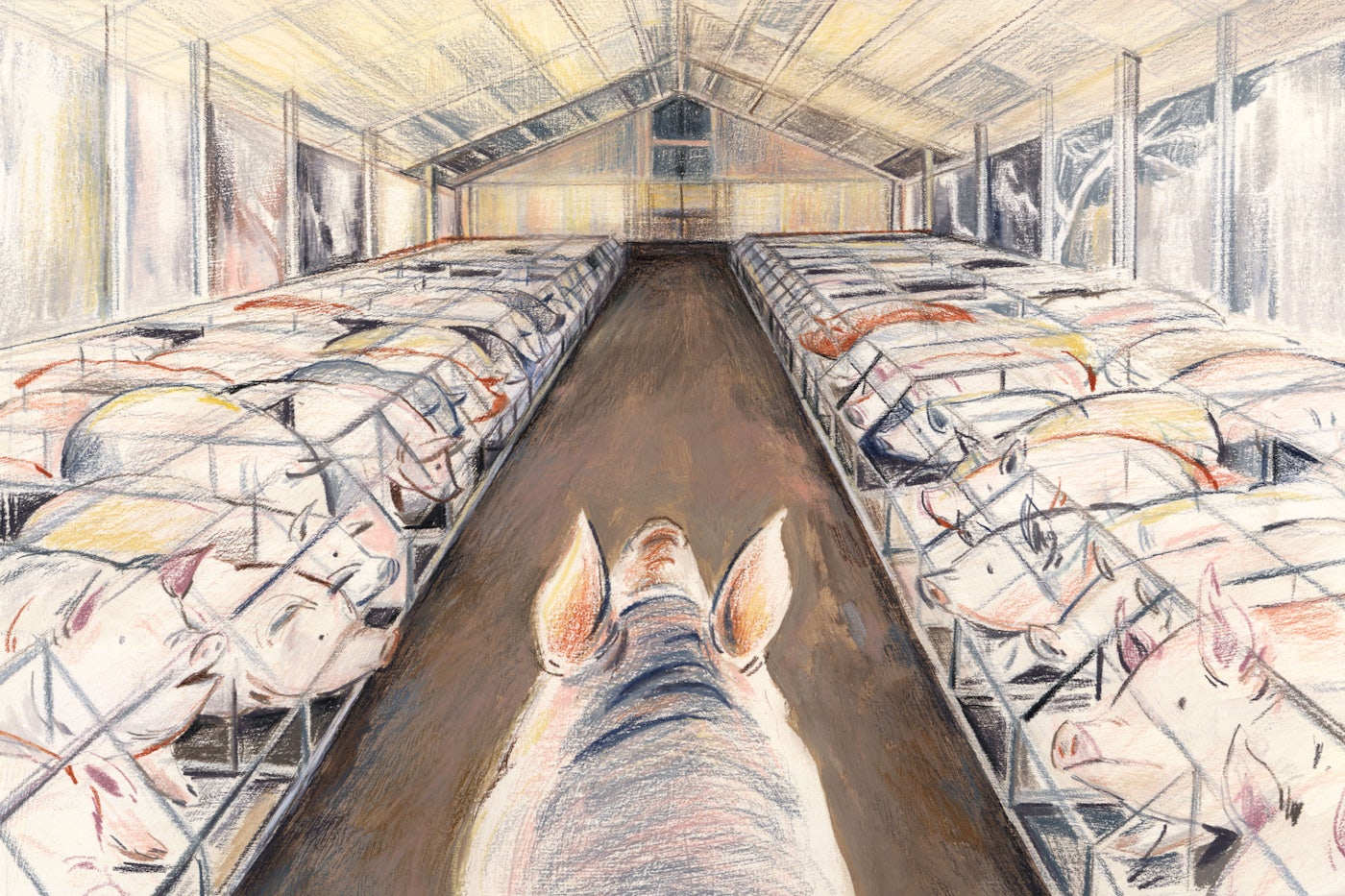

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY DENG

It isn’t spoken of much, but a significant chunk of the Kansas economy depends on pervasive violations of its anti-bestiality laws. In 2010, the Kansas legislature revised the state’s “criminal sodomy” statute—historically vague laws criminalizing multiple forms of nonprocreative sex—to delete language that criminalized consensual gay sex. But it preserved other itemized crimes in the law, including making “sodomy between a person and an animal” punishable by up to six months in prison, defining the crime to encompass “any penetration of the female sex organ by … any object.” Although it made allowances for “generally recognized health care practices,” it offered no exemption for everyday animal breeding. This makes Kansas an outlier. The overwhelming majority of states that use similar laws to criminalize sex between animals and humans provide precisely such an exemption. With the explosive growth of artificial insemination in the past 30 years, much meat production in the United States depends on forcibly inserting objects into female animals’ genitals.

For decades, the meat industry in America has been running up against the contradictions in how Americans conceptualize animal cruelty. A growing number of Americans claim to care about animal welfare and support animal welfare legislation. But the average American consumes over 200 pounds of flesh and 600 pounds of dairy products each year, most of it sourced from animals raised on concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, or fattened on concentrated feedlots. Farmed animals have few meaningful legal protections and are routinely subject to forced confinement, painful practices like castration and tail-docking, and sexually invasive interventions such as artificial insemination. How Americans claim they want to treat animals and how American animals are actually treated are two very different things, and in bestiality laws, these contradictions are laid bare.Bestiality, a highly stigmatized act, lends itself well to loud denunciations but not so much to moral consistency.

Surely when the Kansas legislature voted to prohibit criminal sodomy in 2010, it did not intend to ban artificial insemination. But the letter of Kansas’s law—which would weigh heavily in an actual court case, particularly with a textualist court—is unambiguous. While a specious reading of the “health care” exemption might be stretched to encompass artificial insemination by veterinarians, most artificial insemination is done by low-wage manual laborers. This would make virtually every farm in the state a hotbed of bestiality.

The unsavory reality is that the labyrinthine structure of American bestiality laws derives from a contradiction most consumers would find unpalatable: Many people wish to protect animals from abuse, but the system of industrial meat and dairy production they patronize depends upon practices that would not only horrify them if they were done to dogs and cats but would often be patently illegal. If animal farming had to confront the cruelty of the insemination practices by which its product is created, cheap meat and milk production would be impossible.

Anti-bestiality laws have a long and twisted history. In the colonial period, bestiality was classed with other forms of “unnatural” sex, including homosexual sex, fornication, oral sex, and masturbation, in various “sodomy” and “crimes against nature” statutes whose broad target was any form of nonprocreative sex outside of marriage. Among those acts, bestiality was the most severely punished, and it resulted in at least seven executions. Colonists believed that bestiality was a violation of a divinely established natural order and, thus, they executed not only the human transgressors but also animals, which were seen as conspirators in, rather than victims of, the crime.

But these anti-sodomy laws, written in rather figurative language, were flexible and evolved alongside changing sexual mores. By the mid-nineteenth century, courts turned to sodomy statutes to prosecute cases of sexual assault with male victims (nineteenth-century rape statutes were written to criminalize only sexual assault against women). Not until after World War II, during what historian David Johnson calls “the lavender scare” conflating homosexuality and Communist sympathy, were anti-sodomy laws consistently used to police consensual gay sex.Breeding technicians insert an arm into the cow’s anus to manually flatten the bovine cervix prior to insertion of a “breeding gun.”

When many states in the latter half of the twentieth century repealed sodomy statutes now primarily associated with homophobia, they also—in the process—axed the anti-bestiality laws. Sparked by equal parts horror and embarrassment when sensational cases of interspecies sex could not be prosecuted, state legislatures then moved to recriminalize it. With the assistance of the Humane Society of the United States, 27 states have enacted specific anti-bestiality statutes since 1990. Bestiality remains legal in four states (Wyoming, West Virginia, New Mexico, and Hawaii), while 19 other states have statutes that date to the nineteenth century or even the Colonial period.

These new statutes are distinct from older sodomy statutes in that they define the proscribed acts with precision. They apply the legal definitions for sexual contact found elsewhere in criminal codes to circumstances where one party is an animal, usually (as in Kansas) defining it as any contact between the body, genitals, or wielded object of a human and the genitals of an animal. These statutes also explicitly treat animals as victims worthy of moral consideration, with many explicitly naming the proscribed crime as “animal sexual abuse.”

Cognitive dissonance has haunted these statutes from their inception: Bestiality, a highly stigmatized act, lends itself well to loud denunciations but not so much to moral consistency. Former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, for instance—infamous for racial profiling accusations, constructing the “Tent City” outdoor jail in the Arizona desert where inmates regularly suffered from heatstroke, and organizing a “posse” to round up undocumented immigrants—played a pivotal role in the passage of Arizona’s 2006 anti-bestiality statute, and zealously enforced it: In 2016, he posted fake Craigslist ads around the country to lure bestialists to Arizona where he could arrest and prosecute them. But Arpaio’s sympathy—unsurprisingly, given that he rarely extended it to humans—was highly selective: He happily scarfed down hamburgers at political meet-and-greets, despite most cattle suffering just as much as the abused dogs and cats for which Arpaio established a no-kill rescue shelter inside an abandoned prison.

As the laws were evolving, so was agriculture. While the meat industry had been dominated by consolidated, high-volume slaughter and processing since the nineteenth century, pro-big-farming government policy and corporate agribusiness-backed regulations accelerated this trend and spread it throughout the farming world in the late twentieth. Consolidation and ever-tightening margins drove the meat industry to discover new efficiencies and untapped profits in the bodies of livestock animals. The industry itself refers to this as “commodity” animal production: Thanks to the sophisticated tools of modern life sciences and genetics, animals themselves are mass-produced to be interchangeable in ways that were unimaginable 50 years ago.

Artificial insemination stands out as a uniquely powerful technology to standardize animal reproduction. It allows farms both to produce homogeneous animals and to standardize the breeding process itself, removing the inconvenience and unpredictability of letting animals breed the old-fashioned way. For example, it allows factory farms to sync the estrous cycles of entire barns of animals, which, in turn, maximizes the efficiency of impregnation, gestation, and birthing. In other words, artificial insemination allows farms to guarantee that animals breed on the market’s clock rather than their own biological one. The global market in livestock semen for artificial insemination also ensures ever-more-sophisticated interventions in animal genetics: Breeders are no longer limited by their own (or neighbor’s) prized studs; they can use semen from animals all around the world. And refrigeration means that particularly valuable animals often continue to stud even long after they have died and been ground into sausage.

Artificial insemination was first developed to improve the productivity of dairy cattle immediately after World War II. Dairy cattle must be continually impregnated to give milk and must be spatially confined to be milked. These logistical details made artificial insemination a good fit for most dairy farms, and farmers could expect to offset its higher capital and labor costs with considerable productivity gains. By 1960, the practice had become the dairy industry standard in the U.S. By the 1970s, it was also increasingly used in turkey production, where it helped farmers manage low fertility rates and the unusual seasonality of demand imposed by Thanksgiving. Pork and beef producers saw little promise in the technology until CAFOs farming—which was pioneered with chicken megafarms as early as the 1950s—began to dominate pork and dairy production starting in the 1980s.The legal distinction between artificial insemination and bestiality was not a foregone conclusion. Rather, it is the product of the lobbying power of large farms.

CAFOs, in which animals—rather than grazing or foraging as naturally inclined—are raised in tightly confined quarters, meant that animal reproduction could be centralized on a smaller number of high-volume breeding farms. Wage-laborers could then cheaply inseminate an endless stream of animals, creating the economies of scale needed to make artificial insemination profitable. By the 1990s, it was making inroads in the pork industry; by 2000, it was employed on 70 percent of farms. Today, it is “near-universal,” and the beef industry is undergoing a similar transformation. Only in broiler chicken production is artificial insemination still relatively rare. Chickens, the most-eaten animal in America, are bred in such massive quantities and have such high fertility that for now the technology has not been seen as cost-effective; but even there, experts speculate that it is only a matter of time before industry consolidation, the cheapness of the technology, and the production gains it enables push the industry past a tipping point. To put it bluntly, artificial insemination is so pervasive in industrial agriculture that, if it were prohibited over concerns for animal welfare, much industrial meat and dairy production would grind to a halt overnight.

The legal distinction between artificial insemination and bestiality was not a foregone conclusion. Rather, it is the product of the lobbying power of large farms.

As state legislatures began proposing anti-bestiality laws in the 1990s, the agriculture lobby repeatedly opposed the bills due largely to concerns they would criminalize artificial insemination. Missouri offered a particularly clear example of the process. In 2000, Sheila Rilenge, executive director of the Missouri Alliance for Animal Abuse Legislation, explained to the state’s legislature that animals needed sexual protection from the state: “There is no consensual sex with an animal.… They are unable to speak out loud about this abuse.” But this argument ran afoul of the state’s agricultural lobby, and the proposed anti-bestiality law Rilenge was testifying for died in committee, where an identical bill had also perished in 1999. The chairman of the Judiciary Committee, a rancher named Morris Westfall, feared that the law would be used to prosecute veterinarians and farmers who harvested semen from bulls and artificially inseminated cows. Westfall blocked another version of the bill in 2001. The following year, the legislature finally passed a version of the statute that included a blanket exemption for “accepted animal husbandry, farming and ranching practices or generally accepted veterinary medical practices.”

Of the 27 states that have enacted bestiality statutes since 1990, 24 include nearly identical exemptions for animal husbandry. (Kansas, Iowa, and Delaware’s laws do not.) With the exemptions included, agricultural interests in many states have gone from covertly opposing anti-bestiality bills to either staying mum or even lobbying for them—an alleged sign of their commitment to animal welfare. Only in New Hampshire in 2016 did the farming lobby put up Missouri-esque unconditional resistance to anti-bestiality laws, driven by concerns from small, low-volume dairy farmers that they weren’t large enough to qualify for the law’s exception.

Artificial insemination is a clinical and detached term for a practice that involves invasive and sustained bodily contact between humans and animals. Anthropologist Alex Blanchette, who worked in the field as part of his ethnographic study of a massive Midwestern hog farm in the early 2010s, described it in visceral detail: “Our bodies were meant to act as mere weights, imitating the back pressure of a boar’s mounting until the sow’s uterine muscle contractions draw the semen in through a catheter-like spirette attached to a plastic bag.” Pig production textbooks refer to all this extensive human-animal contact unironically as a “courtship.” Novel artificial insemination technology like post-cervical artificial insemination is even more invasive than what Blanchette describes, requiring workers to deposit semen in the uterus through a catheter rod that penetrates past the cervix. For cattle, breeding technicians insert an arm into the cow’s anus to manually flatten the bovine cervix prior to insertion of a “breeding gun.”

Meat and dairy production currently account for 14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the United Nations.

If modern farms are factories, breeding animals are reproductive machines, micromanaged to maximize their fecundity. The volume and standardization of livestock on modern farms makes artificial insemination profitable, but it can only be profitably managed through ongoing systematic cruelty. After insemination, workers on some farms inject sows with drugs to ensure farrowing occurs at precisely 114 days and within regular working hours. Humans will generally also be present to midwife the ever-larger litters: Intensive selective breeding has pushed sow fertility well beyond what pig bodies can naturally sustain.

Sows on many farms now often farrow more piglets than they have teats, leading to both fatal pregnancies and the pervasive problem of low birth weights and “runts,” animals born too weak and sickly to survive on their own and either killed or nursed back to health by farmworkers. As for the sows, when they do not immediately return to estrus, they are sometimes fed or injected drugs to jump-start their cycles again. After a few cycles of this, when their sexual organs wear out or lose productivity, sows will be killed and their used-up bodies, unfit for full cuts of meat, will be ground up for pepperoni or pet food.

The co-evolution of CAFOs and artificial insemination have made the two difficult to disentangle. Feedlot-style farming is what made the technology cost-effective in the first place. And artificial insemination, in turn, has expanded the production capacities of industrial agriculture; with razor-thin profit margins, farms that resist the technology and other high-production practices are destined for obsolescence. As a result, artificial insemination is increasingly affecting animals’ lives not just directly through unnatural and painful impregnation practices but also by supporting an entire system of inhumane practices.

And the effects aren’t just limited to animals. The litany of harms caused by factory farms, including poisoning local communities with dangerous air pollution, land-clearing and deforestation for feed crops, water contamination, and even meat production’s heavy greenhouse gas emissions are all compounded by the sheer scale of production on megafarms, itself in large part the result of industrialized breeding techniques like artificial insemination. Meat and dairy production currently account for 14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the United Nations.

Many Americans claim to care about animal welfare but are a bit hazy on the specifics. Some, like Arpaio, may imagine that animal abuse involves a few sadistic bad apples engaging in the sorts of brazen cruelty that animal rights groups often expose through undercover videos. The reality is that conventional animal agriculture is routinely abusive in ways that are perfectly legal.

The U.S. does not have meaningful federal standards for on-farm animal welfare. The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act of 1958 only applies to slaughterhouses and is spottily enforced. As a result, animal welfare is in the hands of states, where the political heft of the meat industry ensures that efforts to reduce animal suffering routinely exempt farms. The meat industry has been strikingly effective at gutting regulations (for instance by lobbying for privatized safety inspections at meat plants) and escaping public scrutiny (through support for so-called “ag-gag” laws that criminalize whistleblowing about animal abuse on farms) in ways that increase profits at the expense of workers, consumers, animals, and the environment.

Taking on the meat and dairy industry is a herculean task. But most other forms of animal abuse, sexual or otherwise, are trivial by comparison. The cruelty of some pet owners decried by dog and cat rescues, for example, is a drop in the ocean compared to the sustained abuse our food system accepts as a given. This is the perverse irony of the Humane Society’s pivotal role in bestiality recriminalization. By pushing for laws that exempt farms, the Humane Society helped to install a legal regime that normalizes and even exhorts practices that it considers intolerable when done to pets. Such laws may be a small victory for pet-lovers and liberal sensibilities, but they harden the cruel boundary between companion animals and livestock ever more.

If we were consistent with our concerns, we would recognize that the most common source of harm to animals, sexual or otherwise, is industrial agriculture. That this system is legal has a lot to do with agricultural interests skewing the law-making process, but it has just as much to do with most Americans choosing to look away from the harms caused by a system in which they participate on a daily basis. We may feel justified in locking up “perverse” animal abusers, but we’re willing to stomach the ones who feed us three meals a day.

TNR December 11, 2020

Gabriel N. Rosenberg @gnrosenberg

Gabriel N. Rosenberg teaches at Duke University and is the Duke Endowment Fellow of the National Humanities Center.

Gabriel N. Rosenberg teaches at Duke University and is the Duke Endowment Fellow of the National Humanities Center.

Jan Dutkiewicz @jan_dutkiewicz

Jan Dutkiewicz is a postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University in Montreal and a visiting fellow in the Animal Law and Policy Program at Harvard University.

SEE

No comments:

Post a Comment