“People are getting retriggered with each new calamity in a way that’s paralyzing. The level of grieving is almost electric.”

Brianna SacksBuzzFeed News Reporter

Posted on July 16, 2021, at 2:00 p.m. ET

Cole Burston / AFP via Getty Images

A man holds his head as he attends an impromptu vigil at an anti–Canada Day event titled "No Pride in Genocide" in Toronto, July 1, 2021, to encourage reflection on Canada's treatment of Indigenous people following the discovery of unmarked graves at residential schools in Canada.

Since the remains of more than 1,000 Indigenous children were found buried at former boarding schools in Canada, survivors and their descendants on the US side of the border expressed their own share of outrage and heartbreak, filling Facebook and other social media platforms with personal stories of brutal treatment and even more death.

“Sheldon Jackson [College in Alaska] was run by Presbyterians. They abused my mother and her sisters and killed her twin sister,” a survivor wrote in a Facebook group.

Another survivor commented that he went to this “hell school from the 60s to the 70s and [he] remember[ed] the mean nuns, all of there names.”

“I hated that school Dzilthnaodithhle community school [in New Mexico] I was one of the kids who was abused,” another shared.

As the communal, intergenerational trauma continues to build, advocates and leaders in the US are gearing up for a reckoning that’s just beginning and could create an unprecedented need for culturally informed mental health services. After First Nation officials announced the first set of hundreds of unmarked graves in May, the Canadian government’s dedicated helpline saw more than triple its typical calls from Indigenous people seeking counseling or other crisis-related services, a spokesperson told BuzzFeed News. But in the US, Native Americans continue to carry the grief they’ve held for generations largely without official recognition or support — even though the scale of abuse and death is likely much worse.

The US had a far more extensive boarding school system than Canada, which has acknowledged the family separations, abuse, and killings as cultural genocide in a report by its Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Meanwhile, in the US, the history of stolen children has been hidden, and a government investigation into the unknown number of deaths was only recently announced. From the 1800s to the 1970s, the US forced tens of thousands of children into hundreds of government-sponsored schools, many of whom never came home, their families never being told what had happened. Nearly every Native American has a parent, grandparent, or other relative who survived the abusive system, and the recent headlines have triggered horrific memories and resurfaced traumatic family histories.

“We haven't even begun the truth-telling,” said Denise Lajimodiere, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa who has been interviewing survivors for 14 years, starting with her own parents. “And talking about it is so traumatizing. One man I spoke to touched the back of his head and said, ‘The stories will stay here.’”

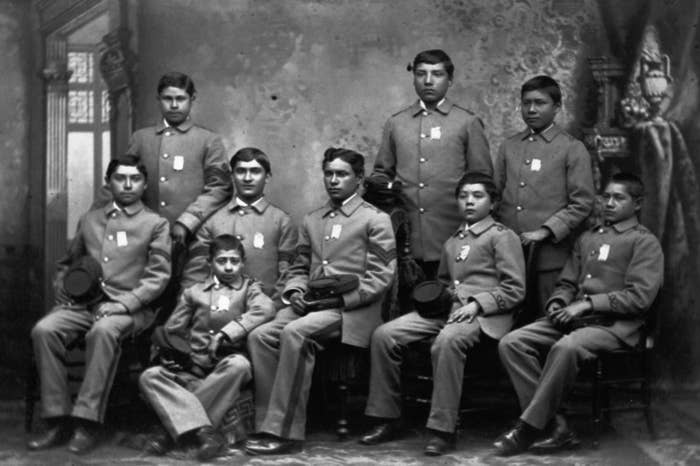

Between 1819 and 1978, US law promoted the “civilization” of Native Americans, leading to the creation of boarding and industrial schools that forced children from their families.

Historical / Corbis via Getty Images

Native American students at Carlisle School in Pennsylvania between 1876 and 1896

The point of these schools, as the founder of Pennsylvania's Carlisle Indian Industrial School infamously put it, was to “kill the Indian in him, save the man” by erasing students’ culture and making them talk, act, and look like white, Christian Americans. When the children arrived, officials — some directly employed by the government and some by church groups — cut their hair, took their clothes, changed their names, and mostly prohibited them from having contact with their families. At many schools, children were beaten for saying hello in their own language; they were malnourished and sexually abused. They were forced to perform tough manual labor for families through "outing programs" during the summers and when they got back to school, crammed into dirty dorms where infections would sweep through their ranks. And when they died, whether from disease, neglect, or abuse, their classmates were sometimes forced to bury their bodies in mass graves, according to multiple reports, UN filings, and BuzzFeed News interviews with the descendants of survivors.

Canada modeled its residential schools on the US boarding system and, since embarking on a truth and reconciliation process in 2007, determined that more than 150,000 Indigenous children attended 139 schools, and as many as 6,000 of them are estimated to have died. Thanks to ground-penetrating radars, search teams in Canada have been able to find evidence of those deaths, often in unmarked graves beneath the grounds of former schools. The new technology, Native American leaders told BuzzFeed News, has resulted in gruesome discoveries of children’s remains that will likely continue.

In May, the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation announced it had found the remains of 215 children, some as young as 3, buried on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Less than a month later, 751 unmarked graves were found at the former Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan. The discovery of an additional 182 unmarked graves near the St. Eugene Residential School was then announced June 30, and work is continuing to determine if they contain the remains of students. On Monday, the Penelakut Tribe in British Columbia said that it had found more than 160 "undocumented and unmarked” graves at the former Kuper Island Indian Residential School.

Anadolu Agency / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Lower Kootenay Band said remains of 182 people were found in unmarked graves close to the former St. Eugene's Mission School near Cranbrook, British Columbia. A present-day cemetery is in the vicinity of the unmarked graves.

But in the US, there has never been an official count of how many students died in these institutions. Instead, for years, a small group of tribes and advocates have been trying to piece together the history. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition has catalogued more than 370 schools in 29 states, each with a graveyard. Since 2012, the group of Native American leaders and researchers has been trying to pry loose federal boarding school records and remains from museums, universities, and institutions like the National Archives and Records Administration so that family members of the stolen children can find out what happened to them. With almost three times as many schools operating in the US as in Canada, the death toll may be staggering.

This largely hidden chapter of American history is finally set to get an official telling. Last month, Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a citizen of the Pueblo of Laguna whose grandparents survived boarding schools, ordered a formal investigation to “uncover the truth about the loss of human life and the lasting consequences.” Since the Interior Department oversaw the schools for more than 100 years, employees will now review historic government records to identify possible burial sites. A report is due in April 2022.

Native American advocates and community leaders applauded the action, saying justice and recognition have been long overdue. But before the US begins a national reckoning on its own cultural genocide, they say they desperately need more immediate mental and emotional health services in their communities, where they’re already seeing a spike in depression, unhealthy coping mechanisms, and other related issues.

The challenges are stark: Indian Country has some of the highest rates of depression, PTSD, domestic violence, and substance abuse in the country — in part, according to Lajmodiere and other researchers, because of the trauma and atrocities from the boarding school era that have trickled down generations. In 2019, suicide was the second-leading cause of death for younger American Indians and Alaska Natives, especially teens. Then the pandemic hit, killing Native Americans at a rate higher than any other ethnic group in the US.

Stacy Bohlen, CEO of the National Indian Health Board, said they were already pushing for more mental health support because of the post-traumatic stress disorder left behind by the pandemic. With the new investigation into boarding school deaths, she and other advocates have been concerned by the lack of a concerted effort by federal or state governments to plan for a new round of trauma.

The handful of Native American groups that have been offering some support have brought back troubling reports about what people are experiencing, she said.

“Devastated is not the appropriate word. They’re annihilated. It’s like they’re walking around in a space and time continuum that is disconnected, in a daze,” she said. “People are getting retriggered with each new calamity in a way that’s paralyzing. The level of grieving is almost electric.”

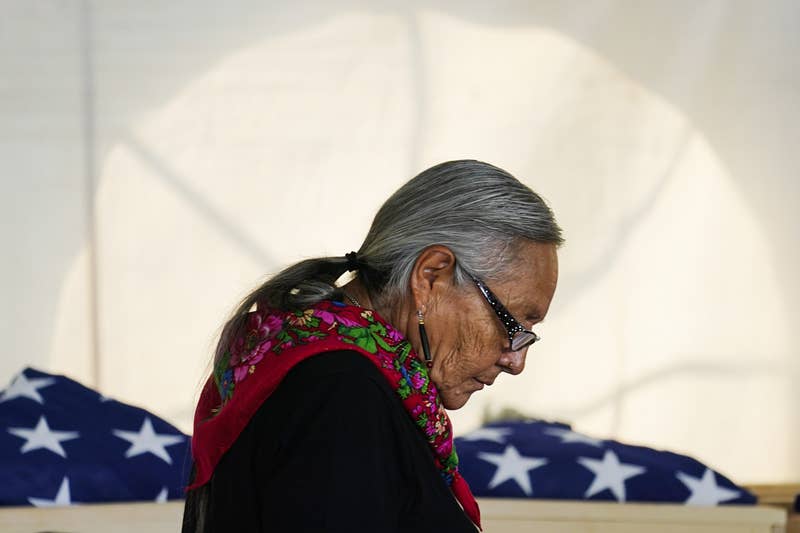

Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press via AP

Kamloops Indian Residential School survivor Evelyn Camille, 82, pauses while speaking about her experience at the school, July 15, 2021.

To appropriately respond, Bohlen said the federal government needs to embrace, for the first time, a sweeping public health approach to prevent further harm as well as put tribal leaders in charge of how the resources are allocated so that they can build their own systems. Most importantly, she said, the US must honor and create official spaces in which survivors can share their stories, as it did for those who lived through the Holocaust. Human rights atrocities are nothing new; there’s a playbook, she pointed out.

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, Haaland’s office acknowledged the need and said they’re working on solutions.

“As we engage in this work, front of mind is creating a safe space for people to share information and seek resources,” Melissa Schwartz, Haaland’s communications director, said. “We recognize the need for this and are working on ways to meet that need. We don’t have that set up just yet, but we will advise the public as soon as we do.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who has apologized for claiming Native heritage in the past, worked with Haaland last year on a bill for the US to create its own truth and healing commission. Though that effort died in committee, Warren has said she plans to reintroduce the legislation in the coming weeks.

"The horrific revelations surrounding Native American boarding schools have renewed suffering and trauma for Native communities, and the federal government must act to right these wrongs,” Warren said in a statement to BuzzFeed News. “I have long fought for support for the mental health and wellbeing of Native people across this country, and I will keep pushing for action that empowers tribal nations and Native communities to address these crucial challenges."

The ability to be heard, acknowledged, and validated by your country is powerful and essential to healing, Angela White, executive director for the Indian Residential School Survivors Society Canada (IRSSS) told BuzzFeed News. In contrast to the US, Canada created the infrastructure for this type of work more than a decade ago.

In 2007, as part of a formal apology and settlement with residential school survivors, the largest class-action lawsuit in the country’s history, the government created a financial compensation system and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. For years, the commission created opportunities for thousands of former students or their descendants to share their experiences, part of a pathway to healing. Officials also obtained boarding school records from government institutions and churches, making them available to families. Although the commission formally wrapped up in 2015, government-funded services like the IRSSS remain because, as White puts it, “intergenerational survivors and everyone in between still need help.”

During a regular year, the nonprofit fields about 140,000 contacts on a variety of issues. But after the announcements about the hundreds of graves at multiple schools, the phones would not stop ringing. In May, the organization threw up a crisis line specifically for residential school survivors and descendants and sent five staff members directly to Kamloops. The response was overwhelming. Thousands of people were contacting the organization every day, seeking a culturally safe space where they could process emotions or simply have someone validate what they saw or experienced as children, White said.

“Because they were told they would not be believed by these nuns, priests, and teachers, that broke down their entire self-esteem and as years went on, no one did believe them, no one wanted to hear them or see them until now when it's been put in our faces,” White said. “If these services weren’t available, you would be seeing more and more self-harm, alcohol and drug-related deaths. Our goal is to limit those as much as we can.”

Indigenous Services Canada also reported a drastic increase in calls, jumping 265% at the end of May and then reaching a peak of 481 calls in a single day on June 1, a spokesperson told BuzzFeed News. KUU-US Crisis Line Society, which serves Indigenous people in British Columbia, noticed such a spike in need that they planned to implement chat and text options.

And what many callers are looking for, White said, is someone who understands their culture and where they are coming from. While having any mental health provider on the other end of the line is helpful, the Canadian organizations learned that it is imperative to culturally train staff and recruit those who can serve the needs of their tribes and communities. More than half of the cases handled by White’s group are for culturally specific healing services, she said.

“If the United States is going to do this, I would make sure they get it right immediately and not have it as an afterthought,” she said. “They need to set up a crisis line. They need to set up cultural spaces or amplify what they already have and start trainings for trauma-informed care. They also need to recruit those well into their healing journey. If you're not well into your healing journey already, this job is not for you.”

Matt Rourke / AP

Ione Quigley, the Rosebud Sioux's historic preservation officer at the US Army's Carlisle Barracks, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, July 14, 2021. The disinterred remains of nine Native American children who died more than a century ago while attending a government-run school in Pennsylvania were headed home to Rosebud Sioux tribal lands in South Dakota after a ceremony returning them to relatives.

Even with resources, healing can be a difficult and complex journey. Those who survived the boarding schools never learned what it was like to have parents or to be held, comforted, or told they were loved. They grew up and became parents themselves.

“They didn’t know how to be parents, so they beat us like they were beaten in boarding school. They were never told they were loved or hugged, so we were never told we were loved or hugged,” Lajimodiere said. “That was my experience, and in my research I heard that over and over.”

It’s a difficult cycle to break. Lajimodiere grew up with an alcoholic, abusive father. Her grandparents, who were stuffed into a closet when they misbehaved, were beaten and forced to kneel on brooms for merely being children. When Lajimodiere had a daughter, she struggled to tell her child that she loved her.

But through her work, in which she connected with other children of survivors, she saw she was far from alone. It wasn’t really her father, she realized — it was what happened to him. Seeing his place in the bigger picture allowed her to finally forgive him.

“We are only as healthy as our secrets,” she said. “To heal, we have to forgive ourselves at a basic level. We have to forgive each other. I had to forgive my father and at some point, my daughter will have to forgive me. And then we can start telling the truth.”

Courtesy Denise Lajimodiere

No comments:

Post a Comment