Sharon Graham’s election as head of Unite shows workers facing new forms of exploitation need strong, diverse unions

That the election of Sharon Graham as Unite’s new general secretary this week took many by surprise says much about today’s union movement and its place in society. At the contest’s outset, many on Unite’s left threw their weight behind one of three white male candidates, accusing Graham of splitting the vote. Throughout the course of the race to replace Len McCluskey, few in the legacy media provided any analysis beyond the election’s implication for the Labour party and Keir Starmer’s leadership; the future of workers’ rights became a sideshow. And as the results trickled in, bemused commentators struggled to understand where the support had come from.

The answer they sought was in the union’s grassroots: ordinary Unite members in workplaces across the country who cared less about Labour party infighting and more about feeding their families, being treated with respect at work, and feeling as if their voices mattered. Labour party insiders, political commentators and opposition candidates might have been blindsided by the election of Unite’s first ever female general secretary on a manifesto of workplace organising, renewed democracy and grassroots power, but rank and file members were not. It’s a lesson Britain’s union movement as a whole must learn if it is to rebuild and thrive

This election mattered because Unite, with 1.4 million members, is one of the country’s biggest trade unions, and trade unions remain the best vehicle ordinary people have to exercise collective power and advance their economic interests. If talking about class struggle in such terms has come to seem divisive, it shouldn’t be: the business interests bankrolling the Tory party have no such qualms about looking out for their own, securing the policies that favour them and the contracts that enrich them. To counter this influence, redistribute power and ensure fairness in the workplace and society at large, we need unions that are strong, democratic and bold.

But too often in recent years, Britain’s labour movement has been defined by decline, infighting and irrelevance. Many have been quick to point out that while Graham’s win might feel like vindication for those overlooked, it still represents the will of only the 12% of members who turned out to vote. Such low turnout is reflective of a long-term decline in membership and participation which, while slowly improving, remains far below its 1970s heyday, with young workers, people of colour and migrants still underrepresented within the movement. The causes are manifold and not all attributable to unions themselves, which have operated for decades under increasingly draconian anti-union laws, a fractured labour market and ever more brazen government cronyism that sees bosses shape public life while their workers aren’t even at the table. But unions must also be prepared to evolve and adapt if they are to survive and be the collective voice Britain’s working class needs in the 21st century.

Perhaps most crucially, the union movement must recognise that the labour market it operates in today is profoundly different from the one upon which it was built. Britain has moved from a manufacturing superpower to a service economy as shipyards and coalmines have made way for retail, care and restaurant jobs. New workplaces have brought new forms of exploitation: the expansion of precarious and insecure contracts; the proliferation of apps that separate workers from each other and from their bosses; and the rise of surveillance technology that has transformed some workplaces into miniature panopticons.

But new challenges can mean new demographics in which to build worker power and enrich the union movement. Grassroots unions such as the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain have spearheaded nationwide strikes among Deliveroo riders and, alongside the GMB, successfully organised Uber drivers in a fight that culminated this year at the supreme court, where it was ruled they should be classed as workers and not contractors. In 2017, their sister union United Voices of the World successfully fought for the “insourcing” of migrant female cleaners at the London School of Economics in what, at the time, was the UK’s largest ever cleaners’ strike. And in 2018, the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU) coordinated an unprecedented fast food strike encompassing McDonald’s, Wetherspoon’s and TGI Fridays workers, many of them first-time trade unionists. Actions such as these prove that taking the risk to focus energy in largely unorganised sectors will pay dividends – but it requires a leap of faith on the part of traditional unions.

In response to difficult political conditions and the shifting of the labour market, much of the union movement has adopted a service model, acting for existing members in something resembling a consumer transaction: join the union and get legal advice, a discounted laptop and individual support in a grievance. But it is organising – the building of power among and between workers so they might ultimately act for themselves – that creates new trade unionists and shifts the dial in society as a whole, not playing whack-a-mole in individual workplaces. The problem that brings a worker to their union should be the start of a transformative journey that sees the issue collectivised, placed within its wider political context, fought for and won, and an active and politically conscious new trade unionist created.

Also vital for the future of the movement will be the meaningful inclusion of previously marginalised workers, not just as figureheads or on siloed diversity committees, but at the heart of union organising. Unions and their democratic structures were built for white, male breadwinners to secure a family wage, a legacy that echoes around the movement today. To act for a new generation of workers will be to restructure union democracy from the bottom up, yielding power to lay members and embracing bold tactics so that the work of anti-racism, trans inclusion, migrant solidarity, disability rights and feminist organising can be union work.

Unions have the ability to transform the lives of individual members and the structure of society as a whole. They are imperfect, but they are what we have and they are ours to shape and strengthen. Unite’s members have recognised that the growth and sustainability of the union movement is in industrial strategy, not party politicking, and in organising workers over servicing members. If the wider movement can learn the lessons of this election, it can once again be a force to be reckoned with.

Eve Livingston is a social affairs journalist and author of Make Bosses Pay: Why We Need Unions

Sharon Graham challenges Jeff Bezos on union rights and warns Labour ‘there will be no blank cheques’

Michael Savage

Sat 28 Aug 2021

The new leader of one of Britain’s biggest unions has vowed to take on Amazon by plotting an international campaign to unionise its warehouses and improve conditions for its workers.

In an interview with the Observer, Sharon Graham, who became Unite’s general secretary last week after a shock victory, said she was in talks with unions in Germany and the US – Amazon’s other major markets – to effectively form a global union campaign that would “pincer” Amazon and force it to allow workers to organise themselves more freely.

Graham said she wanted to deploy “leverage” tactics deployed against difficult employers to convince Amazon to sign a “neutrality agreement”, a document guaranteeing that warehouse workers can form a union without fear of repercussions. The campaign would include lobbying governments in all three countries to use their power as major Amazon customers to pressure it into action.

“I’m talking to the German unions and the American unions because we’re their three biggest markets in both [web services] and e-commerce,” she said. “Let’s work together to get Amazon organised in those three countries. If we do that, we could actually pincer them simultaneously in their three biggest markets. Once we get a neutrality agreement, those workers will join the union. They won’t now because they’re too frightened – they think they’re going to be sacked.

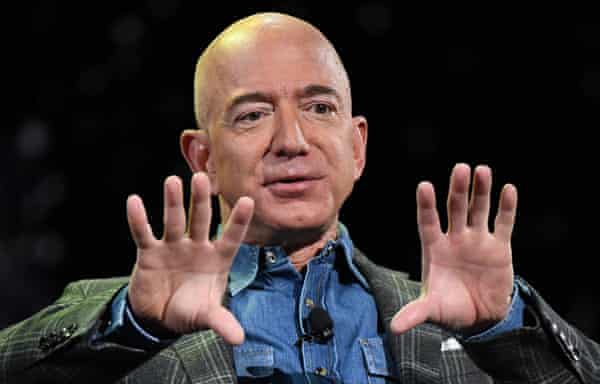

“What I would say to [Amazon founder] Jeff Bezos is he should treat workers fairly, come to the table and sign the neutrality agreement. Eventually, it will have to happen. We’re not going to get bored. If this takes two years, it takes two years. Resources will be allocated. Because if we don’t do that, you ignore the beast who is pace-setting bad behaviour. He may as well come the quick way around. We’re in for the long haul. We could actually crack Amazon. And that would be an amazing thing.”

Amazon has repeatedly been accused of refusing to recognise unions. Last year, the TUC compiled a document in which it said workers had described gruelling conditions, unrealistic productivity targets, surveillance, bogus self-employment and a refusal to recognise or engage with unions unless forced. The company has disputed the claims.

“We respect our employees’ right to join, form or not to join a labour union or other lawful organisation of their own selection without fear of retaliation, intimidation or harassment,” said a spokesperson.

“Across Amazon we place enormous value on having daily conversations with associates, and work to make sure direct engagement with our employees is a strong part of our work culture. The fact is, we already offer excellent pay, excellent benefits and excellent opportunities for career growth, all while working in a safe, modern work environment. The unions know this.”

Graham, who used her leadership campaign to say she wanted to end the union’s heavy involvement in the running of the Labour party, said Keir Starmer’s office had already been in touch about holding a meeting with her following her victory. She said she would demand to know what action Labour was taking to end “fire and rehire” practices.

Amazon intensifies 'severe' effort to discourage first-ever US warehouse union

“I won’t be talking about the leadership of Labour. I won’t be talking about the internal wranglings of Labour. I’ll be talking about fire and rehire, and what is Labour going to do about that issue? When and how are they going to step up to the plate? The Labour party aren’t in power at the moment. A parliamentary Labour party is not going to stop job losses, they’re not going to stop suppression of pay, they’re not going to stop what’s happening to workers out there. So it is not my number one priority.”

She also said that while she would continue to pay the fees Unite hands Labour to be affiliated to the party, any future additional funds would be conditional on Labour being able to prove it was helping Unite’s industrial priorities.

“I will not just be handing over cheques in addition to our affiliation to the club without understanding how that progresses the lot of workers,” she said. “I’m going to be asking, ‘so what are you going to do?’ There won’t be anything additional unless, of course, I can show that it’s important for progressing workers’ issues. I hope Labour do that, because that is part of what they’re there for.”

Graham said she would reform the union into sector-by-sector “combines” – a move designed to increase the union’s power with the most powerful employers.

She said she was “very proud” of the leverage tactics she has deployed against hostile employers, which sees the union target a company’s commercial vulnerabilities such as potential contracts, shareholders or acquisitions, in order to further its goals. She said her “non-traditional” methods were required because persuasion and argument did not work with hostile employers.

“We do a very, very detailed research document looking at every aspect of the company – shareholders, clients, future clients, investments,” she said. “We get into the sinews of the money. We think, ‘OK, what’s more important to them than what they’re trying to do here?’ It’s accountability. Where an employer moves from what I would call normal, acceptable behaviour into very hostile terrain, like sacking workers and then re-employing them, I don’t think we can stand by and watch that happen.

“I will be very deliberate and serious about the plans that we put in place around public sector pay, for example, but also around the private sector. We need to make sure we protect jobs, terms and conditions. And I’ll do anything we need to do to do that.”

No comments:

Post a Comment