BY AMINA KHAN

STAFF WRITER

Los Angeles Times

AUG. 6, 2021

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Friday, Aug. 6. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

It’s become clear that the pandemic has split the country into two Americas: one that considers the virus a critical threat and embraces vaccines, masking and other public health measures, and one that does not. But few probably feel the split as acutely as healthcare workers caring for patients in coronavirus hotspots.

Doctors and nurses in these areas are dealing with two Americas of their own: the one inside hospital walls, where an influx of COVID-19 patients are struggling to breathe; and the one outside, where few seem to acknowledge the full threat of the virus.

That’s the reality for Peyton Thetford, a nurse at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. In the hospital’s intensive care unit, he moves patients from their backs to their stomachs and then onto their sides every two hours to help keep their oxygen levels up. But when he steps outside, he sees hardly anyone wearing masks.

“It’s kind of like the movie ‘Groundhog Day,’ where you wake up and everything’s the exact same and you can’t do anything to change it,” he said. “You’re just coming to work and watching people die.”

Almost all of the COVID-19 deaths these hospital workers are seeing would probably have been avoided if the victims had been vaccinated. But the national campaign to get lifesaving shots into arms has come up against stiff resistance from conservative states in the South and Midwest — areas that, with relatively lower vaccine coverage, are now seeing their COVID-19 caseloads skyrocket.

That’s certainly the case in Alabama, with just 40% of residents 12 and older fully vaccinated, the lowest rate in the nation. There, the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients has jumped in the last month from about 213 to 1,736. If that rate of increase continues, experts warn that within another month, the state’s hospitals could top the January peak of 3,089 patients.

The problem is that many people seem more worried about the vaccine than the virus — even though the virus has accounted for more than 600,000 deaths in the United States alone and left countless others suffering from long-term health consequences.

“I don’t want to be a guinea pig,” said Renee Dunn, 43, a manager of a fast-food restaurant in Heflin, a tiny east Alabama town. She worried that the vaccines were manufactured too quickly, and her mother had a bad reaction to a vaccine this year, suffering sore joints, fever and confusion. Her son, meanwhile, had to miss a few days of work after getting his first COVID-19 shot.

Dunn did say there was something that could change her mind: full FDA approval of a vaccine, which could come as soon as next month. (The vaccines are currently authorized for emergency use after going through clinical trials and an intensive review process.)

Other county residents were more resistant. Pharmacist Ryan Jackson is vaccinated, but he’s heard people voice every argument against getting a shot: fear that vaccines could lead to infertility (they don’t), the belief that the risks of COVID-19 have been exaggerated (they haven’t), and claims that the vaccines contain microchips for government tracking (they do not).

“You hear the conspiracy theories; they don’t trust the government, a lot of political factors,” Jackson said. “It’s just a complete distrust of everybody in authority.”

Much of that vaccine hesitancy falls along well-worn political lines. Americans most likely to reject vaccines, experts say, are those who voted for Donald Trump, live in small towns and rural areas, and are younger than 70.

Still, many GOP leaders have begun to combat anti-vaccine narratives. In Alabama, Republican Gov. Kay Ivey has said it is time for the vaccinated to push back. “It’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, not the regular folks,” she told reporters last month. “It’s the unvaccinated folks that are letting us down.”

Even with Americans divided along these lines, there seems to be some room to move the needle on vaccines. Some conservative states with the highest rates of average daily new coronavirus cases — Alabama among them — are now seeing the biggest jumps in vaccination rates. At his pharmacy, Jackson said he’d also seen an uptick in demand.

“It’s not too late,” he said. “I think the longer we go, people will see that we’re not growing extra limbs and third eyeballs. More people will come around.”

By the numbers

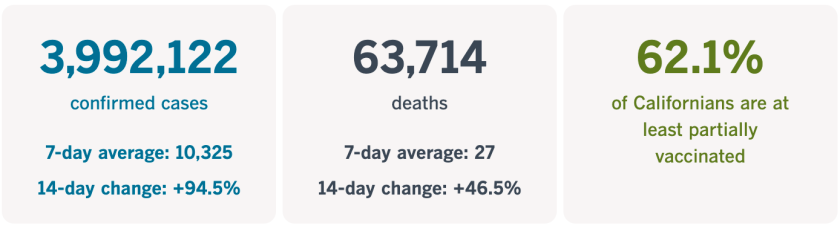

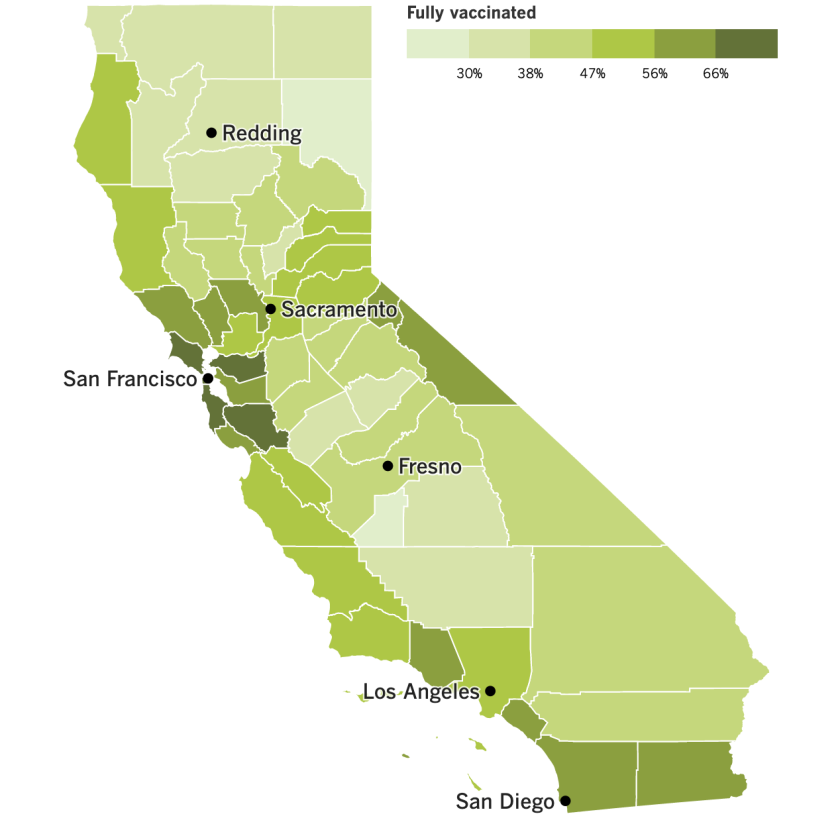

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 10:11 a.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

To boost or not to boost?

It’s no secret that the pandemic has most severely affected the poor — not just the poorest individuals, but the poorest countries as well. The virus is ripping into nations across Africa, where only 1.5 in every 100 people have had at least one shot, and ravaging populous countries such as Indonesia, where vaccination rates are low.

Meanwhile, rich nations such as Germany, France and Israel are moving to provide booster shots to certain groups, such as the elderly. With vaccination rates relatively high, they argue that it helps everyone if they strengthen their own immunity while also looking to help other nations.

That argument didn’t seem to pass muster with the World Health Organization. This week, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus urged mainly well-off, highly vaccinated nations to hold off on offering booster shots until all countries, including poorer ones currently being ravaged by the virus, can provide more of their people with their first shots.

Tedros proposed a nonbinding booster moratorium to be observed at least through September, with a goal of ensuring that all nations first vaccinate at least 10% of their population.

“We cannot, and we should not, accept countries that have already used most of the global supply of vaccines using even more of it while the world’s most vulnerable people remain unprotected,” Tedros said from Geneva.

Some public health experts have said it makes both ethical and practical sense to support the moratorium call. After all, the longer the virus remains in circulation in vulnerable, unvaccinated populations around the world, the more time, money and deaths it will cost. More dangerous variants that crop up in places where the virus can circulate freely will inevitably make their way to those richer nations.

The fact that some countries are moving toward booster shots while much of the world remains unvaccinated is “a moral outrage and a public health miscalculation,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “No country will be safe from this continually mutating virus until all countries have gained access to vaccines.”

Others said they disagreed with the WHO’s call for a moratorium, arguing that there are vulnerable groups within rich countries who need boosters, and denying them an additional shot wouldn’t ease the sharp vaccine disparities between rich and poor countries.

“I strongly disagree with the WHO’s call to restrict booster shots,” Leana Wen, of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, wrote on Twitter. “Yes, we need to get vaccines to the world (which also includes helping with distribution, not just supply), but there are doses expiring here in the US. Why not allow those immunosuppressed to receive them?”

Public health experts say it’s not the first time that the WHO has argued that wealthy countries should be fighting the pandemic beyond their own borders.

“The WHO services 194 sovereign entities, not just the most powerful ones,” said J. Stephen Morrison, the director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “In that sense, Tedros is reflecting the desperation of his constituency — he’s reflecting back the anger, resentment and desperation they’re experiencing right now.”

The Biden administration hasn’t taken a position on the need for booster shots. Still, it appeared to dismiss the need for a moratorium.

“We definitely feel like it’s a false choice, and we can do both,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said.

The U.S. says it has provided more than 110 million vaccine doses to 65 countries. But the WHO said that more than four-fifths of the more than 4 billion doses administered worldwide have gone to a group of wealthier countries that are home to less than half the global population. This is untenable, the agency said.

“We need an urgent reversal from the majority of vaccines going to high-income countries to the majority going to low-income countries,” Tedros said.

Regardless, Morrison said the WHO’s plea was unlikely to alter richer nations’ vaccination policies.

“I don’t think it’ll be effective at stopping rich countries from pursuing it,” he said. “Every day, the list gets longer — there’s a proliferation of countries moving toward boosters.”

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Friday, Aug. 6. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

It’s become clear that the pandemic has split the country into two Americas: one that considers the virus a critical threat and embraces vaccines, masking and other public health measures, and one that does not. But few probably feel the split as acutely as healthcare workers caring for patients in coronavirus hotspots.

Doctors and nurses in these areas are dealing with two Americas of their own: the one inside hospital walls, where an influx of COVID-19 patients are struggling to breathe; and the one outside, where few seem to acknowledge the full threat of the virus.

That’s the reality for Peyton Thetford, a nurse at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. In the hospital’s intensive care unit, he moves patients from their backs to their stomachs and then onto their sides every two hours to help keep their oxygen levels up. But when he steps outside, he sees hardly anyone wearing masks.

“It’s kind of like the movie ‘Groundhog Day,’ where you wake up and everything’s the exact same and you can’t do anything to change it,” he said. “You’re just coming to work and watching people die.”

Almost all of the COVID-19 deaths these hospital workers are seeing would probably have been avoided if the victims had been vaccinated. But the national campaign to get lifesaving shots into arms has come up against stiff resistance from conservative states in the South and Midwest — areas that, with relatively lower vaccine coverage, are now seeing their COVID-19 caseloads skyrocket.

That’s certainly the case in Alabama, with just 40% of residents 12 and older fully vaccinated, the lowest rate in the nation. There, the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients has jumped in the last month from about 213 to 1,736. If that rate of increase continues, experts warn that within another month, the state’s hospitals could top the January peak of 3,089 patients.

The problem is that many people seem more worried about the vaccine than the virus — even though the virus has accounted for more than 600,000 deaths in the United States alone and left countless others suffering from long-term health consequences.

“I don’t want to be a guinea pig,” said Renee Dunn, 43, a manager of a fast-food restaurant in Heflin, a tiny east Alabama town. She worried that the vaccines were manufactured too quickly, and her mother had a bad reaction to a vaccine this year, suffering sore joints, fever and confusion. Her son, meanwhile, had to miss a few days of work after getting his first COVID-19 shot.

Dunn did say there was something that could change her mind: full FDA approval of a vaccine, which could come as soon as next month. (The vaccines are currently authorized for emergency use after going through clinical trials and an intensive review process.)

Other county residents were more resistant. Pharmacist Ryan Jackson is vaccinated, but he’s heard people voice every argument against getting a shot: fear that vaccines could lead to infertility (they don’t), the belief that the risks of COVID-19 have been exaggerated (they haven’t), and claims that the vaccines contain microchips for government tracking (they do not).

“You hear the conspiracy theories; they don’t trust the government, a lot of political factors,” Jackson said. “It’s just a complete distrust of everybody in authority.”

Much of that vaccine hesitancy falls along well-worn political lines. Americans most likely to reject vaccines, experts say, are those who voted for Donald Trump, live in small towns and rural areas, and are younger than 70.

Still, many GOP leaders have begun to combat anti-vaccine narratives. In Alabama, Republican Gov. Kay Ivey has said it is time for the vaccinated to push back. “It’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, not the regular folks,” she told reporters last month. “It’s the unvaccinated folks that are letting us down.”

Even with Americans divided along these lines, there seems to be some room to move the needle on vaccines. Some conservative states with the highest rates of average daily new coronavirus cases — Alabama among them — are now seeing the biggest jumps in vaccination rates. At his pharmacy, Jackson said he’d also seen an uptick in demand.

“It’s not too late,” he said. “I think the longer we go, people will see that we’re not growing extra limbs and third eyeballs. More people will come around.”

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 10:11 a.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

To boost or not to boost?

It’s no secret that the pandemic has most severely affected the poor — not just the poorest individuals, but the poorest countries as well. The virus is ripping into nations across Africa, where only 1.5 in every 100 people have had at least one shot, and ravaging populous countries such as Indonesia, where vaccination rates are low.

Meanwhile, rich nations such as Germany, France and Israel are moving to provide booster shots to certain groups, such as the elderly. With vaccination rates relatively high, they argue that it helps everyone if they strengthen their own immunity while also looking to help other nations.

That argument didn’t seem to pass muster with the World Health Organization. This week, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus urged mainly well-off, highly vaccinated nations to hold off on offering booster shots until all countries, including poorer ones currently being ravaged by the virus, can provide more of their people with their first shots.

Tedros proposed a nonbinding booster moratorium to be observed at least through September, with a goal of ensuring that all nations first vaccinate at least 10% of their population.

“We cannot, and we should not, accept countries that have already used most of the global supply of vaccines using even more of it while the world’s most vulnerable people remain unprotected,” Tedros said from Geneva.

Some public health experts have said it makes both ethical and practical sense to support the moratorium call. After all, the longer the virus remains in circulation in vulnerable, unvaccinated populations around the world, the more time, money and deaths it will cost. More dangerous variants that crop up in places where the virus can circulate freely will inevitably make their way to those richer nations.

The fact that some countries are moving toward booster shots while much of the world remains unvaccinated is “a moral outrage and a public health miscalculation,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “No country will be safe from this continually mutating virus until all countries have gained access to vaccines.”

Others said they disagreed with the WHO’s call for a moratorium, arguing that there are vulnerable groups within rich countries who need boosters, and denying them an additional shot wouldn’t ease the sharp vaccine disparities between rich and poor countries.

“I strongly disagree with the WHO’s call to restrict booster shots,” Leana Wen, of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, wrote on Twitter. “Yes, we need to get vaccines to the world (which also includes helping with distribution, not just supply), but there are doses expiring here in the US. Why not allow those immunosuppressed to receive them?”

Public health experts say it’s not the first time that the WHO has argued that wealthy countries should be fighting the pandemic beyond their own borders.

“The WHO services 194 sovereign entities, not just the most powerful ones,” said J. Stephen Morrison, the director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “In that sense, Tedros is reflecting the desperation of his constituency — he’s reflecting back the anger, resentment and desperation they’re experiencing right now.”

The Biden administration hasn’t taken a position on the need for booster shots. Still, it appeared to dismiss the need for a moratorium.

“We definitely feel like it’s a false choice, and we can do both,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said.

The U.S. says it has provided more than 110 million vaccine doses to 65 countries. But the WHO said that more than four-fifths of the more than 4 billion doses administered worldwide have gone to a group of wealthier countries that are home to less than half the global population. This is untenable, the agency said.

“We need an urgent reversal from the majority of vaccines going to high-income countries to the majority going to low-income countries,” Tedros said.

Regardless, Morrison said the WHO’s plea was unlikely to alter richer nations’ vaccination policies.

“I don’t think it’ll be effective at stopping rich countries from pursuing it,” he said. “Every day, the list gets longer — there’s a proliferation of countries moving toward boosters.”

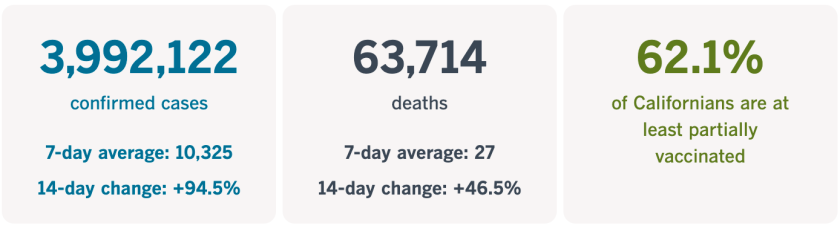

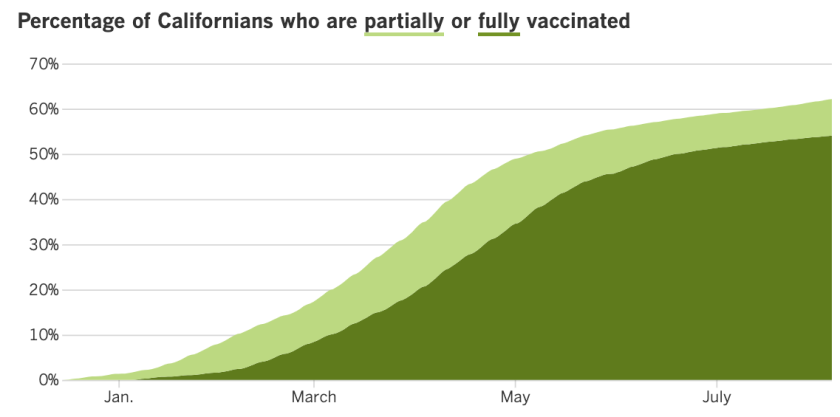

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Coronavirus cases are still ticking upward in Los Angeles County, but at a slower rate, my colleague Luke Money reports — offering a possible sign that the region’s early reinstatement of its mask mandate may be paying off.

The county began requiring everyone, even the fully vaccinated, to wear masks in indoor public spaces in mid-July. And while it’s still early, Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer pointed to some promising numbers. L.A. County saw a 22% rise in reported cases for the week that ended Sunday, compared with the prior week; the rest of California saw a 57% jump in cases over the same period.

“It’s hard to say with 100% certainty that this was the factor that tipped us to have a slightly better slowing of spread than other places,” Ferrer said of the early mask mandate, “but I know for sure it contributed, just because the data [are] really conclusive on the importance of masking indoors and how that does, in fact, reduce transmission.”

Still, as Delta continues to spread, two L.A. City Council members have introduced a proposal to require proof of COVID-19 vaccination for anyone looking to enter indoor public spaces. And the chair of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, Hilda Solis, has issued an executive order that compels county employees to demonstrate that they’ve been vaccinated by early fall.

Solis cited an 18-fold increase in coronavirus cases in the county and a fivefold increase in hospitalizations — mostly involving unvaccinated people — since the county lifted its social distancing restrictions in June and Delta began its inexorable spread.

“As vaccinations continue at a pace slower than what is necessary to slow the spread, the need for immediate action is great,” Solis said.

As the new school year looms, my colleague Howard Blume breaks down some interesting coronavirus data from Los Angeles Unified’s summer school program: Coronavirus infections rose steadily over the five-week program, but ultimately appear to have affected a small share of students and staff.

The rise in infections, detected through regular coronavirus screening, does seem to parallel the rise of the highly contagious Delta variant. Summer school classes started June 21 or 22, depending on grade level, and concluded on July 23. During the first week, the district logged 20 infections among students. During the final week, it recorded 59 infections, with a total of 174 student cases over the five weeks. Among staff, two cases were found the first week and 16 were recorded on the last, for a total of 53 cases over the course of the program.

Most of these cases were contracted off campus, but there were a few that may be related to participating in summer school — a total of 12 cases over the five weeks, 11 of them students. And officials say these figures show no cause for alarm for when schools reopen Aug. 16.

“Yes, the Delta variant is more transmissible. That’s just general knowledge,” said school district medical director Dr. Smita Malhotra. “But our mitigation measures — such as our upgraded ventilation systems, our required masking, our robust testing program — will help to keep our schools as safe as possible.”

The 81st Sturgis Motorcycle Rally kicked off in the Black Hills of South Dakota on Friday, despite the ever-present threat of the Delta variant.

Organizers are expecting at least 700,000 people to descend on Sturgis, home to less than 7,000 residents, during the 10-day event. That’s in spite of the fact that hundreds of participants were infected after last year’s rally, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded appeared to be a “superspreader event.”

Health experts say big gatherings offer fertile ground for the virus to trigger a massive wave of infections, but that didn’t seem to worry rallygoers who said they came to escape the stress and restrictions of life back home.

“I’m going to live free,” said Mike Nowitzke, who made his first trek to the rally from Illinois to celebrate his 50th birthday.

In Latin America, the pandemic has plunged millions of Latin Americans into poverty, and young people are suffering the consequences, my colleague Patrick J. McDonnell reports. Take Marlon Ashanga, a boatman in Peru who loaded his wife, two kids and virus-stricken father into a canoe and guided them three days upriver, deep into the Amazon rainforest.

“People were getting sick everywhere, and we were scared,” recalled Ashanga, a boatman in Belen, a port district of bustling street stalls and homes on stilts. “In the forest, we could rely on natural remedies. And I knew we wouldn’t starve.”

Felipe Solomón Valles went the other way. He was with his wife teaching in a remote village when the contagion hit. The couple and their infant slipped out in a banana boat and trekked through the bush lugging their belongings to escape stay-at-home orders enforced by police, in an effort to reach their families.

More than a year later, both young men, who each survived debilitating cases of COVID-19, now must find ways to support their families in a nation battered by the pandemic. Valles and his wife are unemployed, while Ashanga barely scrapes by.

They’re not alone: The pandemic has plunged millions of Latin Americans into poverty and reversed modest progress toward equality, as young people find themselves caught between surging unemployment and shrinking opportunities.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Does a journalist asking about my vaccination status violate HIPAA?

In a word: No.

You may recall that U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia told a reporter that asking if she was vaccinated was “a violation of my HIPAA rights.” Days later, Dallas Cowboys quarterback Dak Prescott told a reporter asking the same question, “I think that’s HIPAA.”

Both these statements are incorrect, my colleague Jessica Roy explains. Here’s why.

HIPAA, short for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1966, only covers the information that specific healthcare-related entities can share about you without your consent. A journalist asking questions in an interview or news conference is not a healthcare-related entity, and so HIPAA does not apply to them.

“I think that the major thing for people to understand with regard to HIPAA is that it’s very specific,” said Ankit Shah, a pediatrician with a law degree who teaches health law as a lecturer at USC. “Healthcare entities have your information and are prohibited from sharing it without your consent. That’s it. That’s HIPAA.”

“People always apply [HIPAA] to everybody. It’s not applicable to everybody. Only healthcare providers, health plans, and their business associates,” Shah added.

Here’s a helpful list of examples that are totally fine to do and do not in any way violate HIPAA:

A journalist asking someone if they’re vaccinated

A bouncer at a bar requiring proof of vaccination from patrons before they enter

Door-to-door outreach asking whether people are vaccinated

Of course, if someone who is not a healthcare entity asks whether you’re vaccinated, you do not have to tell them. But they’re not violating HIPAA when they ask — and they can choose not to employ you or allow you in for a drink. As Roy put it, “Americans enjoy many rights, but entry to happy hour is not one of them.”

The pandemic in pictures

Yoon Dong Kim, left, and Stacy Kim at Arroyo Cleaners in Pasadena. The Kims bought their first dry cleaner in La Cañada Flintridge in 1988, operating it for nearly three decades as they raised their children.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

For many Korean immigrants in the Southland, owning a dry cleaner has offered a path to a better life for the next generation — though one with struggle and sacrifice, as parents worked 13-hour days and inhaled potentially hazardous chemicals.

But now, many Korean dry cleaners — already dwindling in number before the pandemic — find themselves on the verge of financial collapse, their futures uncertain, as companies consider permanent work-from-home arrangements and office attire grows ever more casual.

This story by my colleague Andrew J. Campa offers a look into the lives of these immigrants — many middle-aged or older — struggling to stay afloat. I was struck by this image of Yoon Dong Kim and Stacy Kim, owners of Arroyo Cleaners in Pasadena, surrounded by their life’s work. Check out the story — it’s well worth a read.

No comments:

Post a Comment