Reasons for Vaccine Optimism

People are complicated.

Charlie Warzel

Mr Lordi of the Finnish hard rock band Lordi gets the second jab of his Covid-19 vaccination.

(JOUNI PORSANGER/Getty)

Welcome to Galaxy Brain — a newsletter from Charlie Warzel about technology and culture. You can read what this is all about here. If you like what you see, consider forwarding it to a friend or two. You can also click the button below to subscribe. And if you’ve been reading, consider going to the paid version.

Reminder: Galaxy Brain has audio versions of the posts for you to enjoy. I’ve partnered with the audio company, Curio, to have all newsletters available in audio form — and they are free for subscribers.

The vaccine hesitancy conversation has (understandably) intensified in the last two weeks, and the undertone of many articles about the Delta variant is some version of: What the hell are we going to do to get this extremely effective vaccine in more people?

One of the first tasks: acknowledge that the unvaccinated are not a monolith.

The Times ran a piece last week that interviewed people all over the country who were vaccine-reluctant but finally got the jab. Their stories provide a helpful look at the variety of reasons — some very understandable (can’t take time off work to go), some very flimsy (afraid of needles, figures others will get it and that’ll be enough) — why people don’t get vaccinated. Then, on Sunday, the paper published a longer profile of unvaccinated Americans, suggesting they fall into two categories: the adamant refusers and those “willing to be swayed.”

In the Atlantic, Ed Yong interviewed Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician and public-health advocate about vaccine hesitancy and how, as a culture, we’re mostly misunderstanding the issue. The interview offers one of the clearest pictures of how our cultural conversations and the language we use don’t capture the nuance of many peoples’ views, especially on something like vaccines. For example, Boyd notes that, in her experience, she’s seeing quite a bit of vaccine hesitancy…among vaccinated people. They took the vaccine, but they’re concerned about the long term effects and aren’t acting as advocates for others in their community to get the shot.

Boyd also suggests that the rampant disinformation from a small but vocal group of anti-vaxxers has created a boomerang effect of sorts. Basically: we (understandably) pay a lot of attention and media lip service to the conspiracy theorists int he anti-vaxx discussion. This creates more vitriol toward the unvaccinated. Boyd argues that plenty of the unvaccinated aren’t even traditional anti-vaxxers to begin with but when they get lumped in, they feel alienated and become less receptive. Yong summed this up succinctly in the piece:

We’re used to thinking of anti-vaxxers as sowing distrust about vaccines. But you’re arguing that they’ve also successfully sown distrust about unvaccinated people, many of whom are now harder to reach because they’ve been broadly demonized.

Boyd is, for the most part, optimistic about vaccine uptake. There is still so much work to be done, she argues, reaching out and creating policy for Americans — especially those who don’t have adequate access to the vaccine (access to the vaccine and vaccine availability are not the same thing, Boyd notes in the interview). There are still so many structural barriers to vaccine adoption that include rural populations, minority communities, the underinsured, issues of child care and time off for people who work inflexible or multiple jobs and don’t want to risk being sidelined by mild (but very real) shot side effects. In other words, there’s plenty of ways to reach and help people get the shots, provided organizations, governments, and interested parties want to put in the work.

Reading Boyd’s interview, I found myself thinking that our very human cultural desire to lump people together into big, binary groups — the pro- and anti-vax — has probably hurt our nationwide vaccination campaign, though it’s unclear just how much. It makes sense that we’re bad at parsing the shades of vaccine hesitancy, simply because vaccination is an emotionally charged topic; I get frustrated very quickly, for example, thinking about those who are pure refusers, needlessly helping prolong the pandemic and potentially helping to create additional variants. And I can’t imagine how frustrated and enraged I’d be if I had kids, whose health and in-person school years are now at risk. (I also want to note that I, too, get uncomfortable reading long profiles, complete with professional portraits of proud vaccine refusers. It feels like another attempt to show empathy toward a group of people who, sometimes gleefully, show a lack of disregard for others.)

But as Boyd notes, it’s also possible that cultural disdain for vaccine refusers is trickling down to some people we can and desperately need to reach. Shaming isn’t working. But vaccine mandates for cultural or work participation might. Google, Disney, and other companies are experimenting with mandating the vaccine (including providing time off for recovery). Airlines could also play an outsized motivating role:

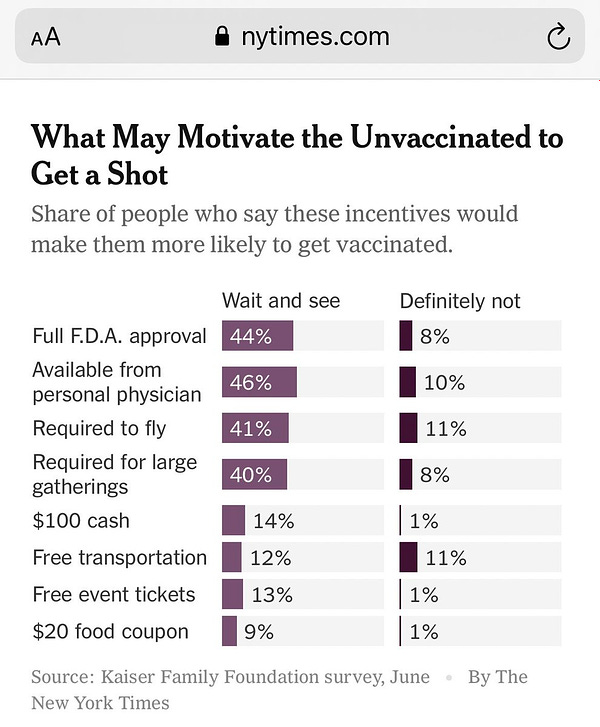

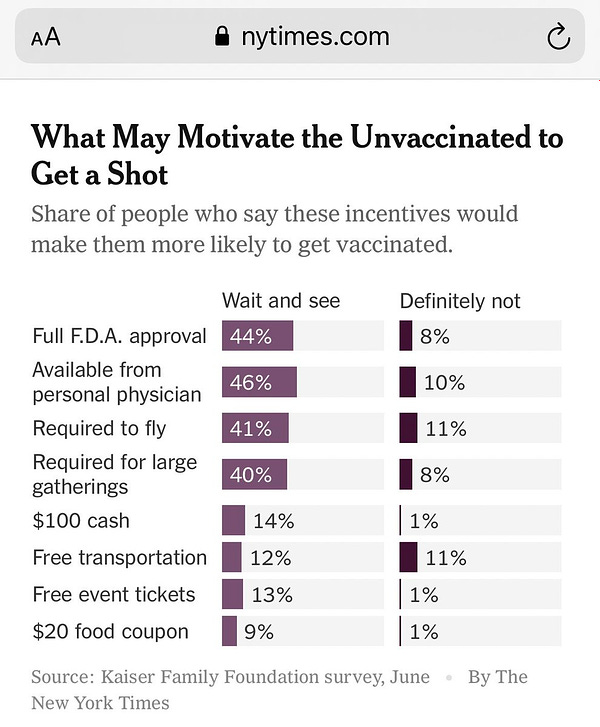

Ken Klippenstein @kenklippensteinPeople who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if they got $100 cash: 14% People who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly: 41%

Ken Klippenstein @kenklippensteinPeople who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if they got $100 cash: 14% People who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly: 41%

August 1st 2021838 Retweets5,914 Likes

But it’s easy, at this point, to feel defeated. This tweet from political scientist Seth Masket feels representative of a viewpoint I hear from the understandably frustrated: many people are just spinning their wheels and putting forth justifications they might not even really believe in. They just straight up don’t want to get the shot.

Last week, Ezra Klein wrote a slightly different version of this argument. Klein asked readers to grapple with the possibility that a solid portion of the unvaccinated may be completely unpersuadable by any rational arguments. “For all the exhortations to respect their concerns,” he wrote, “there is a deep condescension in believing that we’re smart enough to discover or invent some appeal they haven’t yet heard.”

There’s inherent condescension in almost any conversation about the unvaccinated by the vaccinated. The groups think about risk differently and likely have diverging views and levels of trust about science, the media, politicians, etc. Or, in some cases, they don’t! This is the annoying thing about humans — we’re all different in ways that are endlessly frustrating. I’m not trying to give anyone a pass here: I think it’s incredibly dangerous not to get the tremendously effective Covid vaccine and, for those with the means and immune systems to get the shot, I think it’s incredibly selfish and I don’t think being excessively kind to assholes is the way to see change. And yet: it doesn’t matter to those people what I think and conversations plotting how to persuade (like this very newsletter!!) probably sound condescending. Everyone loses!

That said, I’m still convinced that vaccine persuasion is possible, even for some of the deeply resistant groups, given the proper messenger. Last week, Dartmouth professor Brooke Harrington wrote a long, viral Twitter thread arguing that sociological research on fraud victims is incredibly useful for thinking through Covid vaccine resistance.

Harrington argues that resisters are a classic example of a mark — and legitimate victims of a con. But their victimhood becomes a moral failure when, after realizing they’ve been conned, they double down and act as if they’ve been in on the scheme from the beginning. Doing so, she argues, citing research from Erving Goffman, is a way to save face and avoid the “social death” and the humiliation that would accompany confronting the ways in which their belief system had failed them.

But not all hope is lost. Harrington argues that “coolers” — aka, “high-status members of the marks' own communities” — are uniquely capable of “help[ing] reconcile [the marks] to their humiliation & enabl[ing] them to rejoin society without putting the rest of us in danger.”

I called up Harrington to ask her to explain the theory further. She believes that no New York Times columnist or member of the mainstream media would successfully convince an adamant, politically motivated vaccine resistor, no matter what those people say. “Often you’ll hear that these resistors are looking for more information,” she told me. “But they aren’t looking for more information, they’re looking for a new messenger.”

Harrington suggests that many in this group are aware of the facts and smart enough to see that, indeed, the vaccines are quite effective. “The problem,” she said, “is that they have too much to lose from publicly backing off this stance now.”

Which is why some people in highly unvaccinated communities are getting vaccinated in secret or wearing disguises to get vaccinated — vaccination status is deeply baked into their group’s identity and cutting across it could result in a loss of one’s status in that group. Plus, it’s quite painful for anyone to reckon with the ways that their ideology has failed them.

But the right messenger and the right message could move meaningful numbers of politically-motivated vaccine refusers. Harrington suggested that if pro-Trump politicians and news outlets changed their messaging to equate vaccination with ‘owning the libs,’ it could begin to change some minds.

“That message would align vaccination with the overarching norm of their current politics: that conservatives exist to oppose and humiliate liberals,” she told me. “If I were designing the most effective message for somebody like Tucker Carlson, it would be something like, ‘liberals are furious that conservatives are getting vaccinated now because they were hoping we’d all die.’ I’d couch vaccine as act of opposition to liberals.”

I told Harrington I was a bit skeptical. Wouldn’t a massive right-wing reversal feel contrived to the politically-motivated vaccine refusers? Wouldn’t they see through it?

Her short answer: no.

“They’re looking for an out,” Harrington said. “They are smart, they know what’s true and not true. They know ‘Trump vaccine’ is just a word game. But who cares? The function of something like ‘Trump vaccine’ isn’t truth. It’s to act as a plausible face-saving device. So it doesn’t matter.”

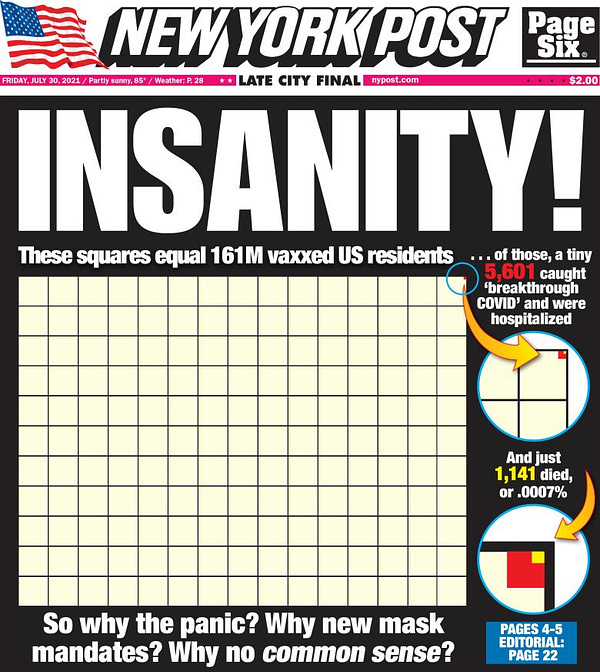

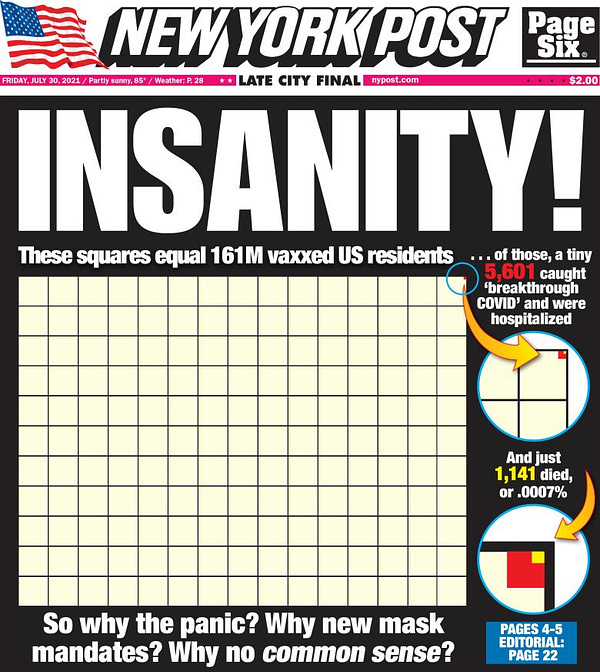

Indeed, we might be seeing the first signs of that messaging from the right. Friday’s Murdoch-owned New York Post cover tried something a bit less intense than Harrington’s suggestion, but trying to tie a pro-vaccine message with popular, politically polarized anti-mask message.

And, when it comes to the politically-motivated vaccine refusers, the rest of us might want to stay out of the discussion if right-wing messaging shifts pro-vaccine. If mainstream media, Joe Biden, or anyone who is an oppositional force chimes in to signal approval, that will taint the message.

We saw a version of this phenomenon in July, when Fox News’ Sean Hannity briefly urged viewers to “take Covid seriously.” The remark drew a fair amount of praise (however tepid) from mainstream journalists as well as mainstream coverage that Fox was perhaps changing its tune on vaccines. The mini news cycle created enough right wing outrage that Hannity backtracked and denied he was trying to get his viewers to take the vaccine.

When it comes to vaccine hesitancy, there’s no tidy conclusion to draw. The substantial pool of Americans who haven’t been vaccinated may share plenty of overlapping characteristics, but they aren’t a monolith, and our strategies have to reflect that. It seems every single American interested in increasing the percentage of fully-vaxxed people in the country has some role to play. Some of us probably need to subsume our (quite understandable rage) and learn new ways to attempt to communicate with people who aren’t completely shut off from persuasion. Those in leadership positions need to channel that frustration into mandate-style policies in workplaces or other services that increase the costs (social, cultural, otherwise) of remaining unvaccinated. And in areas like the mainstream media, what publications and networks say will matter — but maybe not in the ways those organizations think. Persuasion from this group might be impossible and so the best thing for the media to do might be to stay out of that game (when it comes to politically-motivated resistors) and not jeopardize outside efforts.

This might seem counterintuitive, but the lack of tidy conclusions also gives me hope. Don’t get me wrong, the overall climate of disinformation and polarization around a miraculous, quickly produced, life-saving vaccine makes feel great despair. Vaccine resistance highlights some of the ways that trust, shared reality and consensus are almost impossible in this country, even on seemingly open-shut issues of life and death. I’m not wildly optimistic and I’m also anxious even writing a lot of this for fear it’ll be misconstrued as some kind of excusing of vaccine refusers.

But I do think that the broad vaccine conversation has a bigger lesson that we can all learn: people are complicated, and no identity or affinity group is a monolith. When it comes to communication — political or health or otherwise — parsing these groups into finer, more manageable subgroups is crucial. So is learning how to listen and speak to those who are even a tiny bit receptive. Knowing when to give up, shut up, and leave the messaging to someone else — also key. The same can be said for knowing when to increase social costs for those who willfully endanger others.

I don’t believe we’re all going to live in harmony. But I refuse to weather this god awful pandemic without at least trying to learn something useful for the myriad existential battles to come.

Welcome to Galaxy Brain — a newsletter from Charlie Warzel about technology and culture. You can read what this is all about here. If you like what you see, consider forwarding it to a friend or two. You can also click the button below to subscribe. And if you’ve been reading, consider going to the paid version.

Reminder: Galaxy Brain has audio versions of the posts for you to enjoy. I’ve partnered with the audio company, Curio, to have all newsletters available in audio form — and they are free for subscribers.

The vaccine hesitancy conversation has (understandably) intensified in the last two weeks, and the undertone of many articles about the Delta variant is some version of: What the hell are we going to do to get this extremely effective vaccine in more people?

One of the first tasks: acknowledge that the unvaccinated are not a monolith.

The Times ran a piece last week that interviewed people all over the country who were vaccine-reluctant but finally got the jab. Their stories provide a helpful look at the variety of reasons — some very understandable (can’t take time off work to go), some very flimsy (afraid of needles, figures others will get it and that’ll be enough) — why people don’t get vaccinated. Then, on Sunday, the paper published a longer profile of unvaccinated Americans, suggesting they fall into two categories: the adamant refusers and those “willing to be swayed.”

In the Atlantic, Ed Yong interviewed Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician and public-health advocate about vaccine hesitancy and how, as a culture, we’re mostly misunderstanding the issue. The interview offers one of the clearest pictures of how our cultural conversations and the language we use don’t capture the nuance of many peoples’ views, especially on something like vaccines. For example, Boyd notes that, in her experience, she’s seeing quite a bit of vaccine hesitancy…among vaccinated people. They took the vaccine, but they’re concerned about the long term effects and aren’t acting as advocates for others in their community to get the shot.

Boyd also suggests that the rampant disinformation from a small but vocal group of anti-vaxxers has created a boomerang effect of sorts. Basically: we (understandably) pay a lot of attention and media lip service to the conspiracy theorists int he anti-vaxx discussion. This creates more vitriol toward the unvaccinated. Boyd argues that plenty of the unvaccinated aren’t even traditional anti-vaxxers to begin with but when they get lumped in, they feel alienated and become less receptive. Yong summed this up succinctly in the piece:

We’re used to thinking of anti-vaxxers as sowing distrust about vaccines. But you’re arguing that they’ve also successfully sown distrust about unvaccinated people, many of whom are now harder to reach because they’ve been broadly demonized.

Boyd is, for the most part, optimistic about vaccine uptake. There is still so much work to be done, she argues, reaching out and creating policy for Americans — especially those who don’t have adequate access to the vaccine (access to the vaccine and vaccine availability are not the same thing, Boyd notes in the interview). There are still so many structural barriers to vaccine adoption that include rural populations, minority communities, the underinsured, issues of child care and time off for people who work inflexible or multiple jobs and don’t want to risk being sidelined by mild (but very real) shot side effects. In other words, there’s plenty of ways to reach and help people get the shots, provided organizations, governments, and interested parties want to put in the work.

Reading Boyd’s interview, I found myself thinking that our very human cultural desire to lump people together into big, binary groups — the pro- and anti-vax — has probably hurt our nationwide vaccination campaign, though it’s unclear just how much. It makes sense that we’re bad at parsing the shades of vaccine hesitancy, simply because vaccination is an emotionally charged topic; I get frustrated very quickly, for example, thinking about those who are pure refusers, needlessly helping prolong the pandemic and potentially helping to create additional variants. And I can’t imagine how frustrated and enraged I’d be if I had kids, whose health and in-person school years are now at risk. (I also want to note that I, too, get uncomfortable reading long profiles, complete with professional portraits of proud vaccine refusers. It feels like another attempt to show empathy toward a group of people who, sometimes gleefully, show a lack of disregard for others.)

But as Boyd notes, it’s also possible that cultural disdain for vaccine refusers is trickling down to some people we can and desperately need to reach. Shaming isn’t working. But vaccine mandates for cultural or work participation might. Google, Disney, and other companies are experimenting with mandating the vaccine (including providing time off for recovery). Airlines could also play an outsized motivating role:

Ken Klippenstein @kenklippensteinPeople who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if they got $100 cash: 14% People who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly: 41%

Ken Klippenstein @kenklippensteinPeople who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if they got $100 cash: 14% People who say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly: 41%

August 1st 2021838 Retweets5,914 Likes

But it’s easy, at this point, to feel defeated. This tweet from political scientist Seth Masket feels representative of a viewpoint I hear from the understandably frustrated: many people are just spinning their wheels and putting forth justifications they might not even really believe in. They just straight up don’t want to get the shot.

Last week, Ezra Klein wrote a slightly different version of this argument. Klein asked readers to grapple with the possibility that a solid portion of the unvaccinated may be completely unpersuadable by any rational arguments. “For all the exhortations to respect their concerns,” he wrote, “there is a deep condescension in believing that we’re smart enough to discover or invent some appeal they haven’t yet heard.”

There’s inherent condescension in almost any conversation about the unvaccinated by the vaccinated. The groups think about risk differently and likely have diverging views and levels of trust about science, the media, politicians, etc. Or, in some cases, they don’t! This is the annoying thing about humans — we’re all different in ways that are endlessly frustrating. I’m not trying to give anyone a pass here: I think it’s incredibly dangerous not to get the tremendously effective Covid vaccine and, for those with the means and immune systems to get the shot, I think it’s incredibly selfish and I don’t think being excessively kind to assholes is the way to see change. And yet: it doesn’t matter to those people what I think and conversations plotting how to persuade (like this very newsletter!!) probably sound condescending. Everyone loses!

That said, I’m still convinced that vaccine persuasion is possible, even for some of the deeply resistant groups, given the proper messenger. Last week, Dartmouth professor Brooke Harrington wrote a long, viral Twitter thread arguing that sociological research on fraud victims is incredibly useful for thinking through Covid vaccine resistance.

Harrington argues that resisters are a classic example of a mark — and legitimate victims of a con. But their victimhood becomes a moral failure when, after realizing they’ve been conned, they double down and act as if they’ve been in on the scheme from the beginning. Doing so, she argues, citing research from Erving Goffman, is a way to save face and avoid the “social death” and the humiliation that would accompany confronting the ways in which their belief system had failed them.

But not all hope is lost. Harrington argues that “coolers” — aka, “high-status members of the marks' own communities” — are uniquely capable of “help[ing] reconcile [the marks] to their humiliation & enabl[ing] them to rejoin society without putting the rest of us in danger.”

I called up Harrington to ask her to explain the theory further. She believes that no New York Times columnist or member of the mainstream media would successfully convince an adamant, politically motivated vaccine resistor, no matter what those people say. “Often you’ll hear that these resistors are looking for more information,” she told me. “But they aren’t looking for more information, they’re looking for a new messenger.”

Harrington suggests that many in this group are aware of the facts and smart enough to see that, indeed, the vaccines are quite effective. “The problem,” she said, “is that they have too much to lose from publicly backing off this stance now.”

Which is why some people in highly unvaccinated communities are getting vaccinated in secret or wearing disguises to get vaccinated — vaccination status is deeply baked into their group’s identity and cutting across it could result in a loss of one’s status in that group. Plus, it’s quite painful for anyone to reckon with the ways that their ideology has failed them.

But the right messenger and the right message could move meaningful numbers of politically-motivated vaccine refusers. Harrington suggested that if pro-Trump politicians and news outlets changed their messaging to equate vaccination with ‘owning the libs,’ it could begin to change some minds.

“That message would align vaccination with the overarching norm of their current politics: that conservatives exist to oppose and humiliate liberals,” she told me. “If I were designing the most effective message for somebody like Tucker Carlson, it would be something like, ‘liberals are furious that conservatives are getting vaccinated now because they were hoping we’d all die.’ I’d couch vaccine as act of opposition to liberals.”

I told Harrington I was a bit skeptical. Wouldn’t a massive right-wing reversal feel contrived to the politically-motivated vaccine refusers? Wouldn’t they see through it?

Her short answer: no.

“They’re looking for an out,” Harrington said. “They are smart, they know what’s true and not true. They know ‘Trump vaccine’ is just a word game. But who cares? The function of something like ‘Trump vaccine’ isn’t truth. It’s to act as a plausible face-saving device. So it doesn’t matter.”

Indeed, we might be seeing the first signs of that messaging from the right. Friday’s Murdoch-owned New York Post cover tried something a bit less intense than Harrington’s suggestion, but trying to tie a pro-vaccine message with popular, politically polarized anti-mask message.

And, when it comes to the politically-motivated vaccine refusers, the rest of us might want to stay out of the discussion if right-wing messaging shifts pro-vaccine. If mainstream media, Joe Biden, or anyone who is an oppositional force chimes in to signal approval, that will taint the message.

We saw a version of this phenomenon in July, when Fox News’ Sean Hannity briefly urged viewers to “take Covid seriously.” The remark drew a fair amount of praise (however tepid) from mainstream journalists as well as mainstream coverage that Fox was perhaps changing its tune on vaccines. The mini news cycle created enough right wing outrage that Hannity backtracked and denied he was trying to get his viewers to take the vaccine.

When it comes to vaccine hesitancy, there’s no tidy conclusion to draw. The substantial pool of Americans who haven’t been vaccinated may share plenty of overlapping characteristics, but they aren’t a monolith, and our strategies have to reflect that. It seems every single American interested in increasing the percentage of fully-vaxxed people in the country has some role to play. Some of us probably need to subsume our (quite understandable rage) and learn new ways to attempt to communicate with people who aren’t completely shut off from persuasion. Those in leadership positions need to channel that frustration into mandate-style policies in workplaces or other services that increase the costs (social, cultural, otherwise) of remaining unvaccinated. And in areas like the mainstream media, what publications and networks say will matter — but maybe not in the ways those organizations think. Persuasion from this group might be impossible and so the best thing for the media to do might be to stay out of that game (when it comes to politically-motivated resistors) and not jeopardize outside efforts.

This might seem counterintuitive, but the lack of tidy conclusions also gives me hope. Don’t get me wrong, the overall climate of disinformation and polarization around a miraculous, quickly produced, life-saving vaccine makes feel great despair. Vaccine resistance highlights some of the ways that trust, shared reality and consensus are almost impossible in this country, even on seemingly open-shut issues of life and death. I’m not wildly optimistic and I’m also anxious even writing a lot of this for fear it’ll be misconstrued as some kind of excusing of vaccine refusers.

But I do think that the broad vaccine conversation has a bigger lesson that we can all learn: people are complicated, and no identity or affinity group is a monolith. When it comes to communication — political or health or otherwise — parsing these groups into finer, more manageable subgroups is crucial. So is learning how to listen and speak to those who are even a tiny bit receptive. Knowing when to give up, shut up, and leave the messaging to someone else — also key. The same can be said for knowing when to increase social costs for those who willfully endanger others.

I don’t believe we’re all going to live in harmony. But I refuse to weather this god awful pandemic without at least trying to learn something useful for the myriad existential battles to come.

Tom Gara @tomgaraTowards a Murdochian pro-vaccine populism

Tom Gara @tomgaraTowards a Murdochian pro-vaccine populism

No comments:

Post a Comment