How grassroots arts organisations are rising after revolution

Despite a lack of cultural spaces, as well as ongoing political and economic instability, Libyan artists are determined to nurture their diverse arts scene

'War Love' (2016) by Libyan artist Tewa Barnosa (Tewa Barnosa)

By Naima Morelli

26 July 2021

It’s been more than a decade since the killing of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, and the country has been in political upheaval ever since. For young artists working in Libya today, this climate of conflict is challenging, not least due to economic pressures, as survival takes precedence over art.

“Most Libyan artists have been affected by the conflict in some way or another,” says Najlaa Elageli, who founded private arts foundation Noon Arts in 2012. “And their work relays that, sometimes directly and sometimes in a more subtle way.”

“Each is original, personal, and powerful with their chosen methods, and yet they all stand collectively as Libya's artists,” she tells MEE.

Younger Libyan artists like Shefa Salem, above, are "more courageous with their narrative" says Libyan gallerist Najlaa Elageli (Courtesy of Shefa Salem)

Elageli set up Noon Arts to help develop the burgeoning arts scene born out of the revolutionary spirit and to raise awareness of Libyan art on a global scale.

She says that, whereas many of the more established artists - like Mohammed Ben Lamin, Yousef Fetis and Algadaffi Alfkhari, Najla Shawkat and Hadia Gana - tend to reflect on societal concerns from a more retrospective lens, “younger artists seem to be tackling very current themes and are much more courageous with their narrative”.

Libyan artists today are working in very different conditions than under Gaddaffi, when they regularly censored themselves so as not to offend the regime

“Painting, collage, drawing, and sketching are still the main tools for most of the established Libyan artists and a few have also adopted photography as a creative medium or used ceramics and sculpture,” says Elageli, adding that the new generation’s work is “much more experimental”, often utilising digital tools as well as audio-visual installations.

She especially notes the work of emerging artists like Tewa Barnosa, Afra Alashhab, Shefa Salem, and Malak Elghuel, whose work centres around questions of identity, gender and politics.

It’s a huge leap from the conditions under which local artists were working under Gaddaffi, regularly censoring themselves so as not to offend the regime.

“Gaddafi’s absolute authority controlled the economy, politics, and social life of people, and even interfered with the way of people thought,” says 51-year-old Libyan artist Mohamed Abumeis. “The artists’ restriction on their freedom of expression led to an alienation within their homeland.”

Elageli set up Noon Arts to help develop the burgeoning arts scene born out of the revolutionary spirit and to raise awareness of Libyan art on a global scale.

She says that, whereas many of the more established artists - like Mohammed Ben Lamin, Yousef Fetis and Algadaffi Alfkhari, Najla Shawkat and Hadia Gana - tend to reflect on societal concerns from a more retrospective lens, “younger artists seem to be tackling very current themes and are much more courageous with their narrative”.

Libyan artists today are working in very different conditions than under Gaddaffi, when they regularly censored themselves so as not to offend the regime

“Painting, collage, drawing, and sketching are still the main tools for most of the established Libyan artists and a few have also adopted photography as a creative medium or used ceramics and sculpture,” says Elageli, adding that the new generation’s work is “much more experimental”, often utilising digital tools as well as audio-visual installations.

She especially notes the work of emerging artists like Tewa Barnosa, Afra Alashhab, Shefa Salem, and Malak Elghuel, whose work centres around questions of identity, gender and politics.

It’s a huge leap from the conditions under which local artists were working under Gaddaffi, regularly censoring themselves so as not to offend the regime.

“Gaddafi’s absolute authority controlled the economy, politics, and social life of people, and even interfered with the way of people thought,” says 51-year-old Libyan artist Mohamed Abumeis. “The artists’ restriction on their freedom of expression led to an alienation within their homeland.”

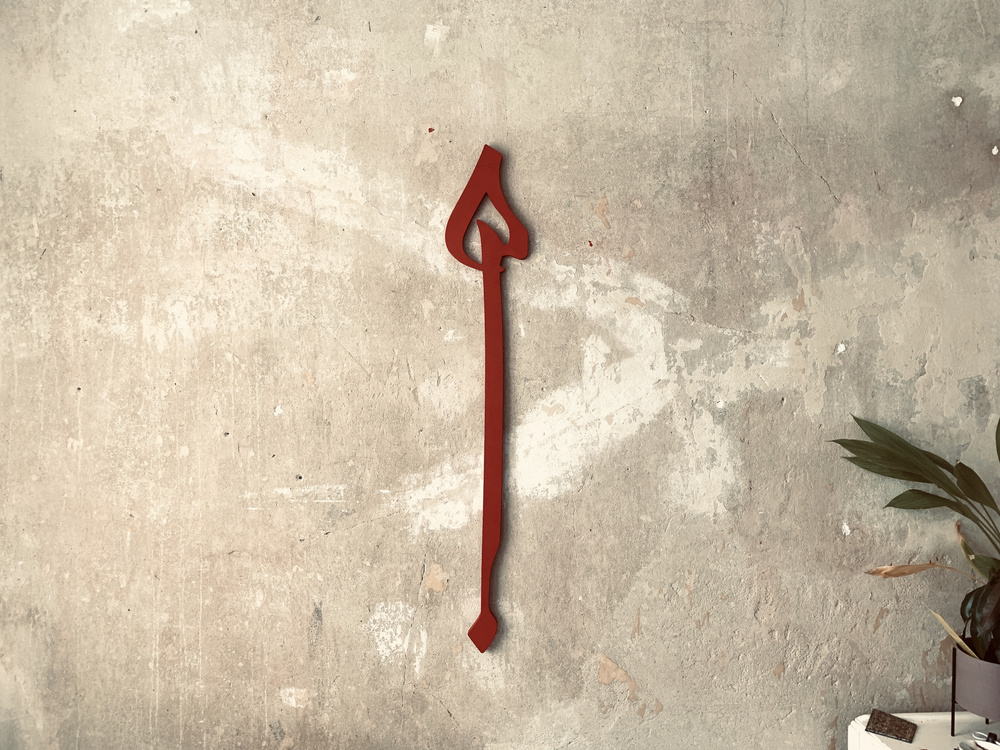

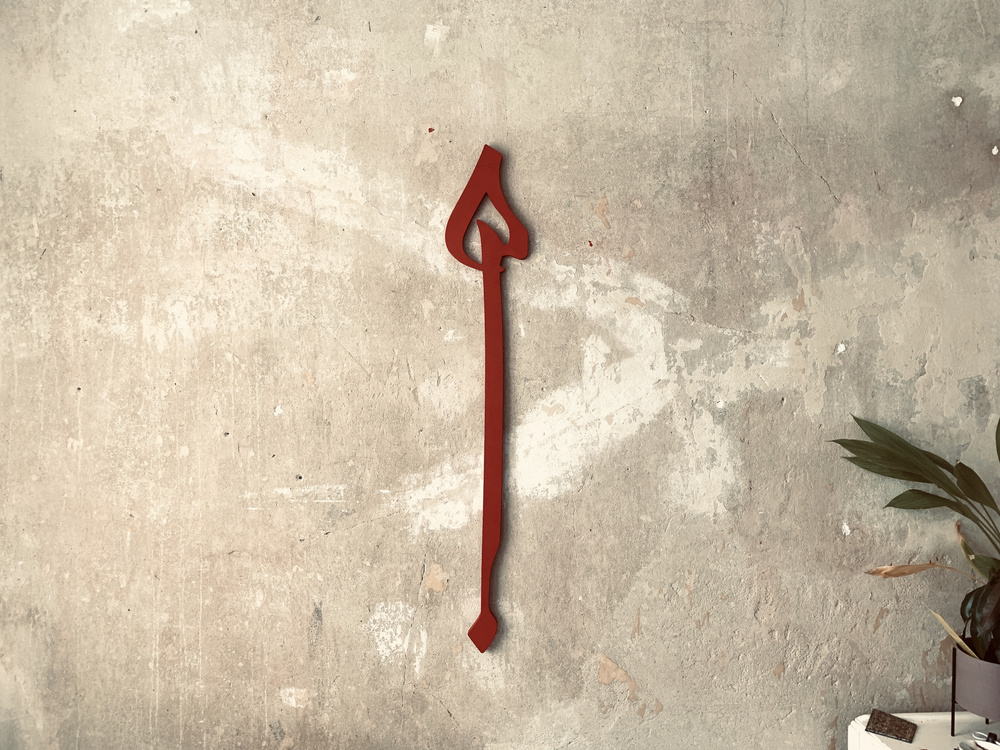

'Sword Love' by artist Tewa Barnosa, who set up NGO and art foundation, WaraQ (Tewa Barnosa)

Post-revolution, artists became more liberated in their choice of subject, but the need to remain sensitive towards issues of religious ideology was still present.

“Before the current conflict, in [early] 2011, the arts scene in Libya was very small and there weren’t many art galleries, and no national museums,” Elageli says. “The Art House in Tripoli was the major cultural art hub where artists had exhibitions, and foreign audiences were able to attend exhibitions and purchase some artworks.”

During that period, some artists might be invited by the Libyan government to exhibit in art fairs in Arab countries and at international art fairs. There were also individual private participations by Libyan artists in exhibitions outside of Libya but, Elageli says, these opportunities were “minimal”.

'Tripoli still has a strong art community, and most artists know each other'

- Faiza Ramadan, Libyan artist

Over the past ten years however, there has been an increase in cultural activity, mainly initiated by NGOs and private foundations. Exhibitions, seminars and street festivals have become more prevalent, with an audience of the general public in mind.

Today, Elageli sees the private initiatives of cultural foundations as the most impactful: "They are holding sustainable exhibitions and seminars that are beginning to have a strong following. I see this as a very promising step.”

Artist Faiza Ramadan, 33, says there has been a notable increase in new art spaces, slowly opening up in the country, the majority of them in the capital: "Tripoli still has a strong art community, being quite small, with most artists knowing each other."

Over the past ten years, Ramadan has attended art exhibitions in Libya and watched as new galleries emerged: “Before the revolution I wasn't very active in the art world, but I did visit exhibitions, which were quite successful.”

While most artists and art initiatives are based in Tripoli, the coastal city of Benghazi is also home to its share of artists although, as 25-year-old painter Shefa Salem notes, the dearth of art spaces there is even more pronounced.

“Exhibitions mostly happen in Tripoli and don't travel outside Libya. In Benghazi, we have only one art space build by the government. It's beautiful and very big, but it's currently empty and in need of restoration,” says Salem. “It opened just before the current conflict [in 2011], and closed almost immediately.”

‘Warning’

One of the main difficulties faced by Libyan artists is funding, which Shatha Sbeta, founder of the online platform De-Orientalizing Art, says “stems from the fact that art is not a necessary good. This makes art marketing and buying - especially in times of global health and consequent financial crises - even more challenging.”

The female Libyan artists featured on Sbeta’s platform receive two thirds of the profits, which she hopes will help incentivise buyers, empower the artists, and promote a new narrative on Libya.

Post-revolution, artists became more liberated in their choice of subject, but the need to remain sensitive towards issues of religious ideology was still present.

“Before the current conflict, in [early] 2011, the arts scene in Libya was very small and there weren’t many art galleries, and no national museums,” Elageli says. “The Art House in Tripoli was the major cultural art hub where artists had exhibitions, and foreign audiences were able to attend exhibitions and purchase some artworks.”

During that period, some artists might be invited by the Libyan government to exhibit in art fairs in Arab countries and at international art fairs. There were also individual private participations by Libyan artists in exhibitions outside of Libya but, Elageli says, these opportunities were “minimal”.

'Tripoli still has a strong art community, and most artists know each other'

- Faiza Ramadan, Libyan artist

Over the past ten years however, there has been an increase in cultural activity, mainly initiated by NGOs and private foundations. Exhibitions, seminars and street festivals have become more prevalent, with an audience of the general public in mind.

Today, Elageli sees the private initiatives of cultural foundations as the most impactful: "They are holding sustainable exhibitions and seminars that are beginning to have a strong following. I see this as a very promising step.”

Artist Faiza Ramadan, 33, says there has been a notable increase in new art spaces, slowly opening up in the country, the majority of them in the capital: "Tripoli still has a strong art community, being quite small, with most artists knowing each other."

Over the past ten years, Ramadan has attended art exhibitions in Libya and watched as new galleries emerged: “Before the revolution I wasn't very active in the art world, but I did visit exhibitions, which were quite successful.”

While most artists and art initiatives are based in Tripoli, the coastal city of Benghazi is also home to its share of artists although, as 25-year-old painter Shefa Salem notes, the dearth of art spaces there is even more pronounced.

“Exhibitions mostly happen in Tripoli and don't travel outside Libya. In Benghazi, we have only one art space build by the government. It's beautiful and very big, but it's currently empty and in need of restoration,” says Salem. “It opened just before the current conflict [in 2011], and closed almost immediately.”

‘Warning’

One of the main difficulties faced by Libyan artists is funding, which Shatha Sbeta, founder of the online platform De-Orientalizing Art, says “stems from the fact that art is not a necessary good. This makes art marketing and buying - especially in times of global health and consequent financial crises - even more challenging.”

The female Libyan artists featured on Sbeta’s platform receive two thirds of the profits, which she hopes will help incentivise buyers, empower the artists, and promote a new narrative on Libya.

Shatha Sbeta offers a platform for female Libyan artists to share their work and get recognition for it (De-Orientalizing Art)

“What I aspire to achieve is whenever someone purchases an art piece, which often comes along with a story, it will ignite conversations among and between this person’s community," Sbeta tells MEE.

Empowering local artists was the motivation for Tewa Barnosa, who founded the NGO and art foundation WaraQ in Tripoli in 2015, after her plans to study abroad were cancelled due to the civil war. Bombing and shelling made it impossible to travel, and the savings she had set aside for her studies were rapidly losing value in light of the deteriorating economic situation.

WaraQ - meaning “paper” in Arabic - became a blank canvas on which emerging artists in Tripoli, including Barnosa herself, could express themselves. They hosted a number of ground-breaking exhibitions that exposed social taboos and the everyday realities of the civil war.

Their 2017 exhibition, Inthaar (which means 'warning' in Arabic), which focused on human rights violations, became notorious after it led to the arts space being forcibly shut down following pressure from “armed individuals" when neighbours reported the exhibition.

In the show, a group of artists shed light on issues such as social chaos, assassinations, disappearance and the kidnapping of journalists and people working in the creative industries. It also highlighted issues related to women’s rights, displacement, and the destruction of the country’s infrastructure.

But, Barnosa says, the general public was outraged by the themes as well as the gender-mixed nature of the space, leading to WaraQ being shut down two weeks after the exhibition.

Barnosa was forced to find other ways to reach audiences, curating projects in public spaces in Tripoli’s old city. WaraQ finally reopened in 2020 with a more nuanced approach to tackling sensitive topics in the local context.

While the Tripoli base is still running, Barnosa herself is now based in Berlin, supporting the local Libyan community with resources she was able to access abroad, like The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) and the Drosos Foundation. She has also partnered with institutions, such as the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung foundation and Reshape Network, as well as expanding WaraQ’s focus on African and Middle Eastern art.

‘Forgetting is not a solution’

Another new artist-run space in Tripoli is the Ali Gana museum, Bayt Ali Gana, which is currently a work in progress.

“It’s evolving depending on the possibilities available,” says founder Hadia Gana, alluding to the complex and unpredictable everyday life in Libya

“What I aspire to achieve is whenever someone purchases an art piece, which often comes along with a story, it will ignite conversations among and between this person’s community," Sbeta tells MEE.

Empowering local artists was the motivation for Tewa Barnosa, who founded the NGO and art foundation WaraQ in Tripoli in 2015, after her plans to study abroad were cancelled due to the civil war. Bombing and shelling made it impossible to travel, and the savings she had set aside for her studies were rapidly losing value in light of the deteriorating economic situation.

WaraQ - meaning “paper” in Arabic - became a blank canvas on which emerging artists in Tripoli, including Barnosa herself, could express themselves. They hosted a number of ground-breaking exhibitions that exposed social taboos and the everyday realities of the civil war.

Their 2017 exhibition, Inthaar (which means 'warning' in Arabic), which focused on human rights violations, became notorious after it led to the arts space being forcibly shut down following pressure from “armed individuals" when neighbours reported the exhibition.

In the show, a group of artists shed light on issues such as social chaos, assassinations, disappearance and the kidnapping of journalists and people working in the creative industries. It also highlighted issues related to women’s rights, displacement, and the destruction of the country’s infrastructure.

But, Barnosa says, the general public was outraged by the themes as well as the gender-mixed nature of the space, leading to WaraQ being shut down two weeks after the exhibition.

Barnosa was forced to find other ways to reach audiences, curating projects in public spaces in Tripoli’s old city. WaraQ finally reopened in 2020 with a more nuanced approach to tackling sensitive topics in the local context.

While the Tripoli base is still running, Barnosa herself is now based in Berlin, supporting the local Libyan community with resources she was able to access abroad, like The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) and the Drosos Foundation. She has also partnered with institutions, such as the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung foundation and Reshape Network, as well as expanding WaraQ’s focus on African and Middle Eastern art.

‘Forgetting is not a solution’

Another new artist-run space in Tripoli is the Ali Gana museum, Bayt Ali Gana, which is currently a work in progress.

“It’s evolving depending on the possibilities available,” says founder Hadia Gana, alluding to the complex and unpredictable everyday life in Libya

.

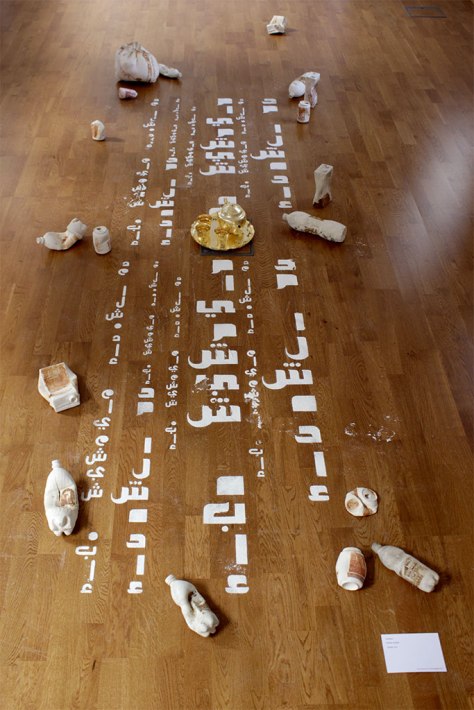

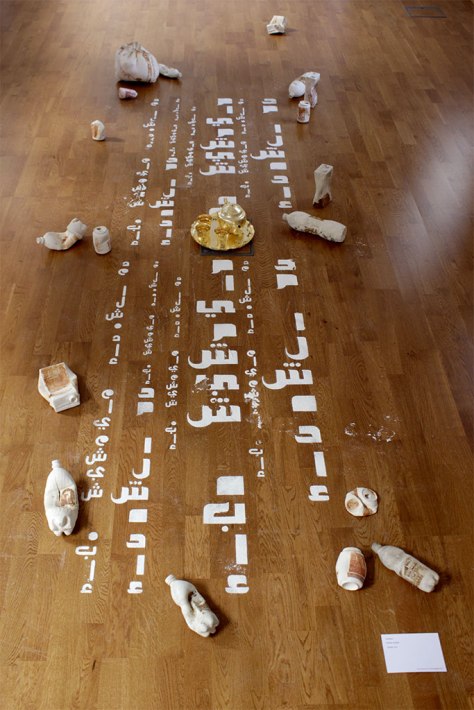

Hadia Gana's 'Zarda' (2012) (Noon Art)

A prominent Libyan artist with a strong ceramics and installation practice, Gana is building the museum in Tripoli’s suburbs and focusing its influence on Libya, with regional and international collaborations.

The museum was conceived in memory of her father Ali Gana, a well-known Libyan intellectual who died in 2006. He was one of the first-generation artists in Libya, teaching art at Tripoli's architecture faculty for several decades and working to preserve the country’s cultural heritage through his writings and teachings.

It was the 2011 revolution that inspired Hadia to establish the Ali Gana Foundation and then the museum in Tripoli, with the mission of offering an inclusive artistic, cultural and educational space.

The idea is to combine the research of new artistic talents while showcasing her father's lifetime of work. When completed, it will be the country’s first art museum, with plans for it to develop into a multi-disciplinary cultural hub.

It will be open to the emerging generations of Libyan artists, who are ready to share new and diverse narratives.

While many Libyan artists understand that through their work, they can educate the public on their country's past and present, especially in light of the lack of documentation and a national archive, Barnosa laments the fact that many of them don’t necessarily address these concerns head on.

“People need to know what is happening in Libya,” Barnosa said, in an interview with Berlin-based Barenzwinger art foundation last year. “I don't think a lot of Libyan artists do this necessarily, actually pointing out the pain and struggles that are happening and saying: ‘Hey, this is going on and we need to think about this rather than forget it’.

“Forgetting is not a solution, we need to think about what is happening and the aftermath. We need to reflect.”

Sbeta believes that one of the most important missions for spaces supporting Libyan art is to move beyond the Eurocentric gaze and orientalist perceptions. "The main mission is to connect cultures through art. This process is very challenging,” she tells MEE. “The fine line that I struggle with the most is how to navigate the cultural contexts along with being inviting and welcoming. I came to realise that storytelling is a great way to combat this.”

A prominent Libyan artist with a strong ceramics and installation practice, Gana is building the museum in Tripoli’s suburbs and focusing its influence on Libya, with regional and international collaborations.

The museum was conceived in memory of her father Ali Gana, a well-known Libyan intellectual who died in 2006. He was one of the first-generation artists in Libya, teaching art at Tripoli's architecture faculty for several decades and working to preserve the country’s cultural heritage through his writings and teachings.

It was the 2011 revolution that inspired Hadia to establish the Ali Gana Foundation and then the museum in Tripoli, with the mission of offering an inclusive artistic, cultural and educational space.

The idea is to combine the research of new artistic talents while showcasing her father's lifetime of work. When completed, it will be the country’s first art museum, with plans for it to develop into a multi-disciplinary cultural hub.

It will be open to the emerging generations of Libyan artists, who are ready to share new and diverse narratives.

While many Libyan artists understand that through their work, they can educate the public on their country's past and present, especially in light of the lack of documentation and a national archive, Barnosa laments the fact that many of them don’t necessarily address these concerns head on.

“People need to know what is happening in Libya,” Barnosa said, in an interview with Berlin-based Barenzwinger art foundation last year. “I don't think a lot of Libyan artists do this necessarily, actually pointing out the pain and struggles that are happening and saying: ‘Hey, this is going on and we need to think about this rather than forget it’.

“Forgetting is not a solution, we need to think about what is happening and the aftermath. We need to reflect.”

Sbeta believes that one of the most important missions for spaces supporting Libyan art is to move beyond the Eurocentric gaze and orientalist perceptions. "The main mission is to connect cultures through art. This process is very challenging,” she tells MEE. “The fine line that I struggle with the most is how to navigate the cultural contexts along with being inviting and welcoming. I came to realise that storytelling is a great way to combat this.”

No comments:

Post a Comment