How Russia “ground down” Ukrainians

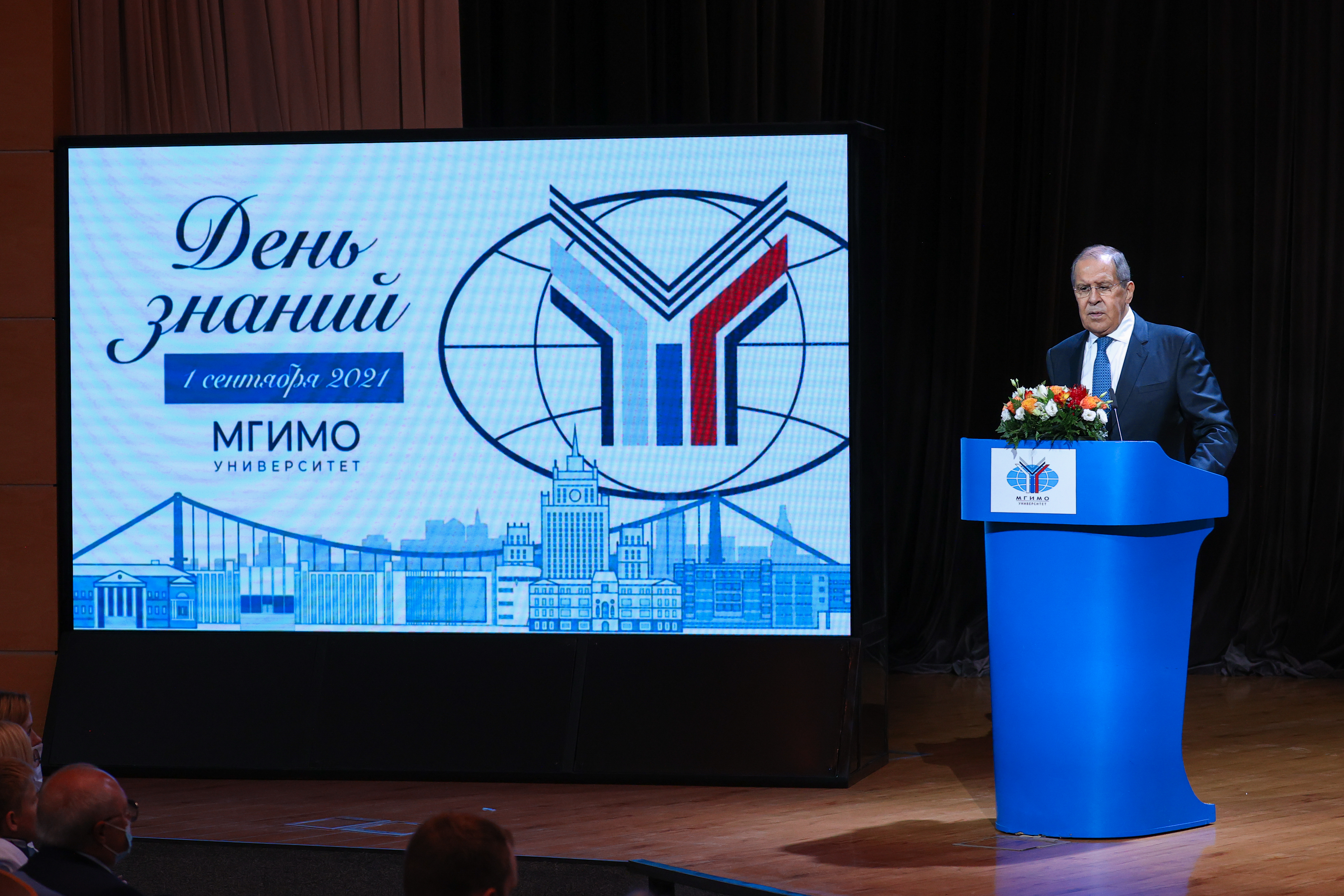

Speaking at the MGIMO University on September 1, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said: "We have never tried to grind down the traditions, culture, language of those peoples who have inhabited the territory of our country since the Russian Empire, then the Soviet Union, and now the Russian Federation.” But then why is the vast majority of languages in Russia endangered? And where have millions of Ukrainians disappeared?

The territory of Russia covers one-eighth of the entire land surface on Earth, with the population constituting 1.9% of the world’s, while languages spoken in Russia account for about 2% of all the world’s languages. At the same time, over 90% of these languages (121 out of 131) are threatened to a varying extent, according to UNESCO assessment. The report says 19 languages are “vulnerable,” while the rest are in an even more critical situation.

In late 2019, a post by a High School of Economics Professor Gasan Guseynov made quite a splash in Russia, where he wrote that in the capital of a multinational country “hosting hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians and Tatars,” nothing is available in languages other than Russian. Perhaps that is why, Guseynov wrote, it seems to some Russians that Russian speakers in Ukraine are unable to learn Ukrainian. The professor was soon fired.

Despite Russia’s rhetoric about its multinational nature and multilingualism, the presidential Hotline only accepts questions in Russian, while letters to Ukrainian political prisoners in Russian prisons won’t be delivered if written in any other language. Federal TV and radio broadcast entirely in Russian as well. It is the only available language of vocational and higher education, including the Single State Exam in secondary school. National languages, on the other hand, have not been mandated in schools since 2018. In September 2019, Albert Razin, a Russian scientist, set himself on fire in defense of the Udmurt language (the number of speakers dropped by a third from 2002 to 2010 alone), protesting against the innovation. The government turned a blind eye to the dramatic move.

According to a 2010 census, some 552,000 Udmurts were living in Russia, along with 1.9 million Ukrainians, making the latter the third-largest ethnic group in the Russian Federation, after Russians and Tatars. They also make up for the world’s largest Ukrainian diaspora. Somewhat fewer (1.3 million) people of Ukrainian descent reside in Canada.

However, overseas it is much easier than in the “sisterly” Russia to remain a Ukrainian, as noted by Forbes. Families are welcome to baptize a child either in a Ukrainian Orthodox or Catholic Church. The child is free to attend a Ukrainian kindergarten, and then, they can learn their native language and history in a municipal secondary school. There are 12 schools like that in Toronto and suburbs, and 25 in the Province of Ontario. In Russia, on the other hand, there are no government schools where Ukrainian is the language of command. Any attempts to open them, as explained by Mykhailo Ratushnyk, head of the Ukrainian World Coordinating Council, immediately get into the FSB focus, with its operatives starting to intimidate the initiators.

“Over the past 20 years, the Ukrainian diaspora in Russia has been under enormous pressure from the government, both at official and unofficial everyday levels,” was mentioned at the V All-Ukraine Research Conference in 2013.

Needless to say, it has become very inconvenient to be a Ukrainian in Russia since 2014.

“If we speak about Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars, they are almost the most disempowered people in Russia. It is simply dangerous to be a Ukrainian or a Crimean Tatar. Going to a Ukrainian church, studying the language (you can do it in Kuban, but as a “Russian dialect,” “Kuban-speak”) – it is all informally prohibited, said Director of the Oleksandr Nykonorov Foreign Policy Research Center and co-coordinator of the “Kuban with Ukraine” Committee Serhii Parkhomenko.

On the other hand, being a Ukrainian had become dangerous in Russia long before 2014.

According to a 1926 census, Ukrainians were the second-largest ethnic group in Russia. Back then, it was 7.8 million people. By the next census, the number more than halved – in 1939, there were just 3.3 million Ukrainians in Soviet Russia. Over the past century, Ukrainians in Russia remained at a quarter of the previous number. Given the circumstances, it would be fair to call it “cultural genocide.”

Kuban

This genocide was most severe in the 1930s when forcible suppression of Ukrainians and their culture started in regions with a historically high Ukrainian population, particularly Kuban.

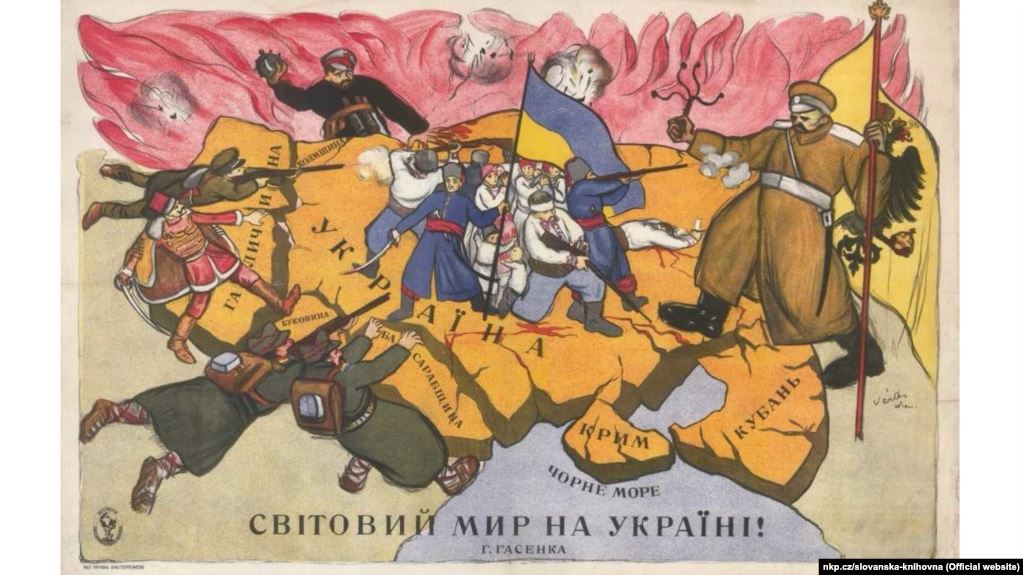

The first general census of the Russian Empire of 1897 recorded more than 900,000 Ukrainian speakers in Kuban (62% of the total population). Manifestations of the Ukrainian culture were so strong in Kuban that soon after the revolution in the Russian Empire, Kuban People’s Republic emerged, and its Legislative Council in 1918 adopted a resolution to join the Ukrainian National Republic in the form of a Federation. The merger never happened due to aggression by Soviet Russia. In 1920, Kuban People's Republic was destroyed by the Bolsheviks. However, insurgent units operated in the Kuban area until 1925.

The Soviet census of 1926 showed there were 915,000 Ukrainians in Kuban. At the time of a 2010 census, there were 84,000 left.

In 1992, film director Valentin Sperkach shot a documentary entitled Cuban Cossacks. For Two Hundred Years Now..., which tells the story of Zaporizhia Cossacks moving to Kuban and the genocide of Ukrainians in Russia.

Its characters open up about their experiences: “Why am I registered as Russian, not Ukrainian... Because we were being strangled, so help us God!.. The entire Krasnodar Krai was made Russian... We were Ukrainians, and now we no longer know who we are. Shapeshifters... In school, I studied in Ukrainian. And we spoke Ukrainian. And since 1933, everything has come to naught.”

On December 14, 1932, the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) and the SNC of the USSR adopted a resolution "On Grain Procurement in Ukraine, the North Caucasus, and the Western region," which radically changed approaches to national policy: the fight against “Petliura's Ukrainization" in the Ukrainian SSR and against any manifestations of Ukrainization in the North Caucasus. The next day, the ban on the use of the Ukrainian language in education, office work, and press was extended to other regions of Soviet Russia with a highly dense Ukrainian population.

This was accompanied by repressions. According to one of the characters of Sperchak's documentary, his family was saved from deportation after his father forbade him to enroll in a Cossack culture club at school. The families of all kids who had signed up were deported.

Far East

Another powerful Ukrainian center outside Ukraine, besides Kuban, was Green Ukraine – a territory in the southern part of the Far East. Based on various estimates, Ukrainians constituted a third to a half of the population in the Far East. In some areas, they even accounted for 60–80% of the population.

“This is a big Malorossiya village. The main and oldest street is Mykolska. Along the entire street, on both sides, white huts are lined up, occasionally still covered with straw... people from the Great Russian counties are barely noticeable among those from Poltava, Chernihiv, Kyiv, Volyn, and other Ukrainians – they vanish among the primary Malorossiya element... People sport Ukrainian clothes. You can hear the joyful, populous, and lively Malorossiya speech everywhere” correspondent Ivan Illich-Svitych wrote, describing the city of Ussuriysk in 1905.

From June 1917 to January 1918, the Provisional Far Eastern Ukrainian National Committee, which was the main executive body of the Ukrainian Far Eastern Republic, was located here in Ussuriysk. Ukrainians also tried to form their state in the Far East.

Throughout its existence, the state-building movement in Green Ukraine focused on unification with the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Second All-Ukraine Congress of the Far East, held in Khabarovsk in January 1918, appealed to the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, demanding that the Russian government recognize Green Ukraine as part of the Ukrainian state.

“Of course, the conditions were hardly auspicious – civil war between the Red and the White armies was already underway in the Far East. Both of them were very negative, even hostile, towards Ukrainians – not only towards their aspiration for independence, but even towards their cultural needs,” said Viacheslav Chornomaz, researcher of the Ukrainian diaspora in the Far East and its representative, editor of the encyclopedia Green Ukraine. Ukrainian Far East.”

But as soon as the 1930s, the Far East turned into a “desert of Ukrainian culture,” said Chornomaz. Ukrainians had no opportunity to preserve their identity.

Siberia

The third center was the Ukrainian communities of Grey Ukraine – the territory of Ukrainian colonization in Siberia. After the February Revolution of 1917, the Ukrainians of Grey Ukraine established their own self-government and military units in Siberia. At the First Ukrainian Congress of Siberia in Omsk in July-August 1917, the Main Ukrainian Council of Siberia was elected.

Ukrainian state movement in Siberia stretched across the regions of Western Siberia, where Ukrainians accounted for the majority of the population. At the time of the Ukrainian governmental movement in Grey Ukraine, Ukrainian press was available, Ukrainian unions and associations were created, and even Ukrainian national rallies were held, flying blue and yellow flags.

After termination of the Ukrainian statehood in Grey Ukraine and the occupation of Western Siberia by the Bolsheviks, the Ukrainian population, which constituted about 40% of the 1.5 million people of Grey Ukraine, was destroyed or assimilated.

Volga Region and Others

In addition to Green and Grey Ukraine, there was also the so-called Yellow Ukraine, an ethnic Ukrainian territory in the Volga region where the presence of Ukrainians was so massive that the German Republic of the Volga region created by the Bolsheviks had three official languages – German, Russian, and Ukrainian – enshrined in the constitution. Moscow, however, never approved the constitution, and the autonomy was soon abolished.

In 1926, Ukrainians made up more than 70% of the population of the Taganrog area but in 1939, the Soviet census showed that most Ukrainians in that region had mysteriously “disappeared.” While Ukrainians accounted for about 40% of the population in the Belgorod region in the 1897 census, the area has become practically mono-ethnic today: 94.4% of the population are Russians.

Today’s Russia

In the aughts, Ukrainian social, cultural, and religious activists in Russia faced attacks, assaults, attempted and completed assassinations. Ukrainian organizations and establishments that emerged on the wave of democratic reforms were eliminated.

In 2003, the vicar of the Moscow parish of St. Ignatius the Godbearer, Bishop Oleksandr Simchenko of Antioch (UGCC) was first assaulted by a group of unidentified men while on an Ivano-Frankivsk – Moscow train. The priest spent several weeks in hospital but no criminal inquiry was opened. After that, he was assaulted five more times. The perpetrators were never found.

In 2002, Volodymyr Poburynnyi, a businessman, philanthropist, and member of the "Dream" Ukrainian Cultural Society was killed in Ivanovo region.

In April 2004, Anatolii Kryl, leader of the Ukrainian choir “Horlytsia” and doctor by profession, was killed in Vladivostok.

In July 2006, Natalia Kovaliova, head of the Audit Commission of the Federal National and Cultural Autonomy of Ukrainians in Russia (FNCAUR), survived an assassination attempt in Tula. Two men attacked her, inflicting multiple grave injuries. A metal rod, found near the crime scene, was used to smash her face, break her teeth, and almost knock out her right eye. The woman suffered a fractured skull and intracranial bleeding.

In December 2006, her husband, Volodymyr Senyshyn, member of the Council of the Union of Ukrainians in Russia and head of the Tula regional organization Parents' Roof, was killed in Tula.

In 2008, the Ukrainian Educational Center was terminated in Moscow.

In 2010, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation revoked registration of one of the two largest public associations of the Ukrainian minority, the Federal National and Cultural Autonomy of Ukrainians in Russia.

In 2010, due to a criminal case, the only official library of Ukrainian literature in Russia was shut down to visitors (and eventually closed altogether in 2018).

In 2012, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation ruled to close the second all-Russian public organization of the Ukrainian minority, the Union of Ukrainians in Russia.

Roman Tsymbaliuk, an UNIAN staff writer in Moscow, said: “Even before the invasion, the Russian authorities had done everything possible to destroy the Ukrainian movement in the Russian Federation.”

Center for Strategic Communications and Information Strategy

How the fall of the Soviet Union 30 years

ago still haunts Ukraine

As western Ukrainians clash with their eastern counterparts, the divides that Soviet authoritarianism masked are reasserting themselves.

By Ido Vock

15 September 2021

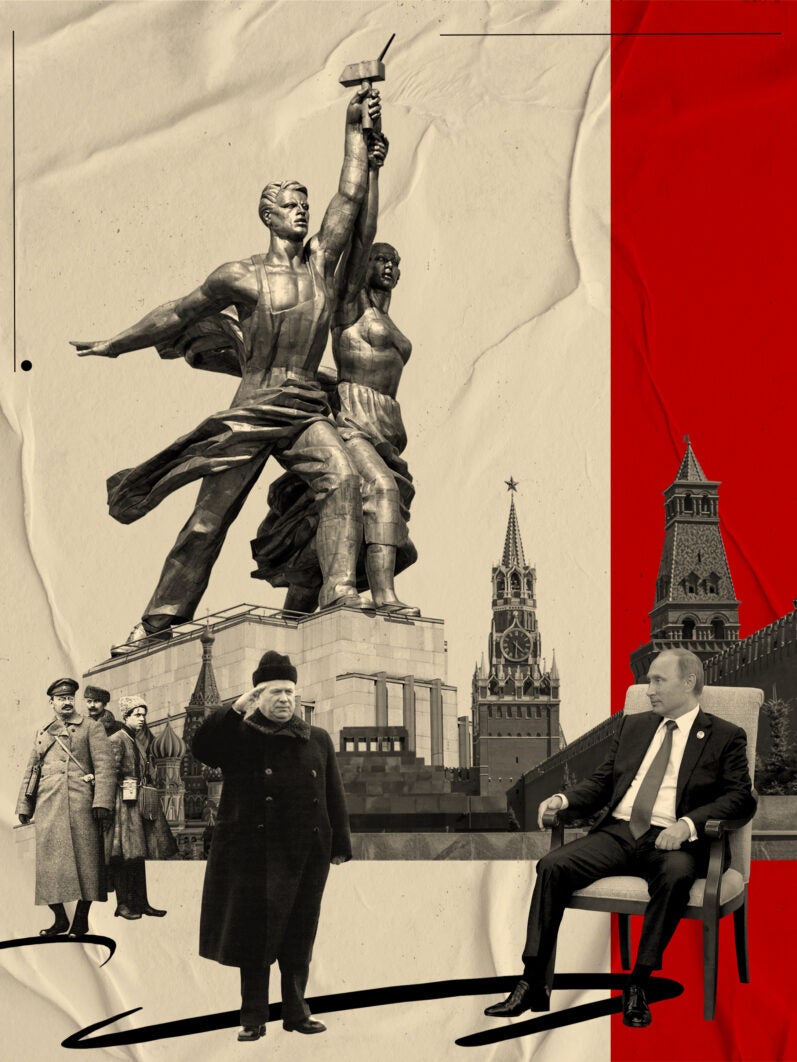

“Russia was robbed,” wrote Vladimir Putin in a 5,000-word essay on “the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians”. Modern Ukraine, Putin argued, “was shaped… on the lands of historical Russia” by the Bolsheviks, who had no regard for the history of Russia.

Putin’s argument is hardly new. Regime figures alternately argue that Ukraine is not a genuine sovereign state; that only its Ukrainian-speaking west is rightfully divided from Russia; or that Ukrainians and Russians are essentially one people, artificially separated. That line of thinking was taken to its extreme in 2014, when Moscow annexed Russian-speaking Crimea, in its view righting a historical wrong. The transfer of the territory from Russia to Ukraine in 1956 had been under the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev; a nominal change at the time that became consequential when the USSR collapsed 30 years ago this December.

The argument is premised on a supposed division between different language groups. In the west of the country, annexed to the USSR in 1940 from Poland, Ukrainian is spoken. In the east and centre of the country, historically part of the Russian empire, Russian is much more common. It is that distinction which Russia plays on to undermine its neighbour’s statehood. The parts of Ukraine that interest the Kremlin are the east and centre: the Crimean peninsula, the borderlands of the Donbass, the Black Sea coast. “Kyiv does not need Donbass,” Putin wrote in his article.

Now geography is reasserting itself in the territories of the former empire, nowhere more so than in Ukraine, where a war continues to be waged between Ukrainian forces and Russian-backed separatists in the country’s east.

***

Lviv, in western Ukraine, only feels like a Soviet city during the drive in. Crumbling abandoned factories line the streets on the outskirts that ring the city. The same blocks of flats that can be seen across the territory of the former socialist empire line the city’s wide boulevards.

Approach the city centre, though, and the urban fabric changes completely. Reinforced concrete gives way to elegant sandstone buildings along cobbled streets. Mid-rise art deco buildings painted in elegant pastels are ornamented with cherubs and sculptures of toned men and women. Trams rattle along the winding roads. This is no longer Lvov, the city’s name in Russian, but Lemberg, as it was known in German under the Austro-Hungarian empire – more Vienna than Volgograd.

The city’s identity has been shaped by the succession of flags that have flown over the town hall. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire following the First World War, it came under Polish rule with the re-establishment of Polish statehood. At the outbreak of the Second World War, eastern Poland was annexed to the USSR, under the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Occupied by the Nazis in 1941, it was back under Soviet control by 1944. Although Lviv is at the centre of what the US historian Timothy Snyder called the “bloodlands” of Europe, it experienced relatively little fighting and, unlike other Polish cities, most of its architecture survived the war. Since 1991, it has been part of independent Ukraine.

In the city’s ethnic make-up, the lines were blurred, as so often in central Europe. Gravestones in the Lychakiv cemetery pay tribute to Lviv’s diverse history. Modern inscriptions in Ukrainian stand next to tombs of Poles and Austrians as well as Soviet-era plaques in Russian celebrating heroes who died defending the socialist motherland from the fascists. The city’s modern homogeneity is a historical anomaly, a product of the Holocaust, which emptied Lviv of its Jews, and of postwar population transfers between Soviet Ukraine and Poland.

This is central, not eastern Europe. Western Ukrainians think of themselves as different from homo sovieticus. “The Austro-Hungarian empire was freer than the Russian empire. People have freedom in their blood here,” one local official told me.

***

An 11-hour journey south on a clattering Soviet-era night train leads to the port of Odessa. At 9:30pm, the night train heaves out of Carpathia on its way to the Black Sea. Passengers pour glasses of vodka and cut slices of sausage in anticipation of the night ahead. I fall asleep as the train leaves behind Lviv’s Austro-Hungarian architecture. Seven hours and a few sudden stops and starts later, I wake as the morning sun peeks behind the window shutters.

The setting as the train pulls into Odessa could be anywhere in the old USSR: grey concrete walls, wheel-less Ladas propped up on breeze blocks, abandoned factories. The train finally arrives at the Black Sea, a giant banner atop the Stalin-era station welcoming visitors to the “hero city of Odessa”, an honour bestowed upon it by the Soviet government for its resistance to the Nazis’ Romanian allies.

Odessa, founded by the Russian empress Catherine the Great on the site of an Ottoman fort in the late 18th-century, has for centuries been as cosmopolitan a city as Lviv. Under the tsars and then the Soviets, Greeks, Armenians and Moldovans mingled with Russians and Ukrainians, forging the city’s reputation for easy-going cosmopolitanism underpinned by a commercial spirit.

Most of all, it was the Jews who made Odessa’s reputation. The city was, at its peak, more than 40 per cent Jewish, the community centred on the neighbourhood of Modovanka, whose gangsters the writer Isaac Babel immortalised in his Odessa Tales. During the tsarist era, rampant anti-Semitism and frequent pogroms, such as that of 1905, are believed to have killed about 400. This undermined the image of Odessan liberalism which would later come to dominate the popular image of the city, as the historian Charles King wrote in Genius and Death in a City of Dreams.

Odessa formed some of the most consequential Jewish politicians of the 20th century, from Leon Trotsky, who studied in the city, to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the father of Revisionist Zionism, whose experience of Odessan anti-Semitism convinced him that Jews would never be welcome within gentile nations and needed a state of their own. “Wasn’t it a mistake on God’s part to put the Jews in Russia, where they suffer as if they’re in hell?” asks the mobster Benya Kirk in the Odessa Tales.

Babel, executed in 1940 by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, did not live to see how much worse life would get for Ukraine’s Jews. As in Lviv, the Holocaust emptied Odessa of the vast majority of its Jewish population, though they retained their cultural imprint on the city. Yiddish-inflected Russian still marks out the city’s distinctive dialect and its famous dry wit.

***

Odessa and Lviv embody the divisions in Ukraine perhaps better than any other cities in the territory that Kyiv controls. Ukrainophone, ex-Austro-Hungarian, central European Lviv contrasts with Odessa, founded by a tsarina, whose reputation was made in the Soviet era.

Ukraine’s linguistic divide is played up by outsiders who know little of the country, says Vladislav Davidzon, the author of From Odessa with Love. He argues that most Ukrainians, equally comfortable in both languages, do not see much political significance in their choice of tongue. Ethnic or linguistic divisions do not map well along political lines. “It’s absolutely true that Russian is the language of Ukraine’s neighbour and historical occupier – but this country has the lowest rate of people speaking the state language of any country in Europe.” (Just 55 per cent of Ukrainians speak Ukrainian at home, according to a 2019 survey by Pew Research.)

But real differences do exist. They revolve around, in particular, views of history. Especially since the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution, which ousted the pro-Russian leader Viktor Yanukovych, a revived Ukrainian nationalism, seeking to distance Ukraine from its Soviet past, lionises figures such as Stepan Bandera, a Second World War-era Ukrainian nationalist leader who pledged allegiance to Hitler. That reading of history appeals to Ukrainians in the west of the country but grates with those living further east.

Signs of the rehabilitation of Bandera and his Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), responsible for wartime anti-Jewish pogroms and the ethnic cleansing of Poles, are manifold in Lviv. A large thoroughfare in Lviv is named Bandera Street. There is also a monument to Bandera and a Heroes of the UPA street.

This expression of nationalism, largely embraced at the national level, alienates those in the east who are more comfortable with the Soviet legacy. It also serves to frighten some Ukrainians from ethnic or religious minority groups, according to Eduard Dolinsky, the director general of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee. “A monument to Bandera is disgusting and a mockery. It’s a monument to a killer on the grave of his victims.”

Vasyl Filipchuk, a former Ukrainian diplomat, argues that western Ukraine’s post-communist rehabilitation of Bandera is one of the biggest obstacles to the creation of a consensual national narrative. It is not surprising that Odessans, coming from a city with impeccably maintained Soviet war memorials such as the Monument to the Unknown Sailor, feel unsettled in Lviv, he says.

***

In May 2014, Odessa was the site of one of the most contentious episodes of the early stages of the Ukrainian Revolution (when pro-EU, anti-Russian protests led to the overthrow of the Ukrainian government). As protesters and pro-Russian counter-demonstrators clashed in the streets, the latter retreated into the Trade Unions House. Shortly afterwards, a fire broke out. Although it is still unclear how the fire started – or which side caused it – the flames quickly spread, killing 46 pro-Russian activists. (Two of the opposing protesters were also killed.)

The episode was seized upon by the Russian state to allege that “Ukrainian nationalists” had massacred peaceful demonstrators expressing their desire not to give up close ties to Russia. It became one of the foundational myths of the pro-Russian separatist movement. Putin’s article this year raised the prospect of similar massacres being committed by “the followers of Bandera” in other Russian-speaking Ukrainian cities.

In the long search for a post-communist national narrative, in common with many of the other newly independent Soviet states, Ukrainian authorities looked to the past to write a new story for their country. Even if the war united many Ukrainians against Russia, the country’s recent embrace of western Ukrainian nationalism risks alienating those who have a different reading of the past. Thirty years after the Soviet Union fell, the divisions its authoritarianism masked continue to perturb Ukraine.

No comments:

Post a Comment