BY AAMER MADHANI AND JONATHAN LEMIRE

• ASSOCIATED PRESS •

SEPTEMBER 15, 2021

President Joe Biden, listens from the East Room of the White House in Washington, on Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021, as he is joined virtually by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, not seen, as he speaks about a national security initiative. (Andrew Harnik/AP)

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden announced Wednesday that the United States is forming a new Indo-Pacific security alliance with Britain and Australia that will allow for greater sharing of defense capabilities — including helping equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines. It’s a move that could deepen a growing chasm in U.S.-China relations.

Biden made the announcement alongside British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who joined him by video to unveil the new alliance, which will be called AUKUS (pronounced AWK-us). The three announced they would quickly turn their attention to developing nuclear-powered submarines for Australia.

“We all recognize the imperative of ensuring peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific over the long term,” said Biden, who said the new alliance reflects a broader trend of key European partners playing a role in the Indo-Pacific. “We need to be able to address both the current strategic environment in the region and how it may evolve.”

None of the leaders mentioned China in their remarks. But the new security alliance is likely to be seen as a provocative move by Beijing, which has repeatedly lashed out at Biden as he’s sought to refocus U.S. foreign policy on the Pacific in the early going of his presidency.

Before the announcement, a senior administration official sought to play down the idea that the alliance was meant to serve as a deterrent against China in the region. The official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to preview the announcement, said the alliance’s creation was not aimed at any one country, and is about a larger effort to sustain engagement and deterrence in the Indo-Pacific by the three nations.

Johnson said the alliance would allow the three English-speaking maritime democracies to strengthen their bonds and sharpen their focus on an increasingly complicated part of the world.

“We will have a new opportunity to reinforce Britain’s place at the leading edge of science and technology, strengthening our national expertise, and perhaps most significant, the U.K., Australia and the U.S. will be joined even more closely together, “ Johnson said.

The three countries have agreed to share information in areas including artificial intelligence, cyber and underwater defense capabilities.

But plans to support Australia acquiring nuclear-powered submarines are certain to catch Beijing’s attention. To date, the only country that the United States has shared nuclear propulsion technology with is Britain. Morrison said Australia is not seeking to develop a nuclear weapons program and information sharing would be limited to helping it develop a submarine fleet.

The Australian prime minister said plans for the nuclear-powered submarines would be developed over the next 18 months and the vessels would be built in Adelaide, Australia.

Australia had announced in 2016 that French company DCNS had beat out bidders from Japan and Germany to build the next generation of submarines in Australia’s largest-ever defense contract.

Top French officials made clear they were unhappy with the deal, which undercuts the DCNS deal.

“The American choice to exclude a European ally and partner such as France from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region, whether in terms of our values or in terms of respect for multilateralism based on the rule of law, shows a lack of coherence that France can only note and regret,” French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and defense minister Florence Parly said in a joint statement.

Morrison said the three countries had “always seen through a similar lens,” but, as the world becomes more complex, “to meet these new challenges, to help deliver the security and stability our region needs, we must now take our partnership to a new level.”

Matt Pottinger, who served as deputy national security adviser in the Trump administration, said that equipping Australia with nuclear-powered submarines was a significant step that would help the U.S. and its allies on the military and diplomatic fronts.

Underwater warfare capabilities have been Beijing’s “Achilles’ heel,” Pottinger said. A nuclear-powered submarine fleet would allow Australia to conduct longer patrols, giving the new alliance a stronger presence in the region.

“When you have a strong military, it provides a backdrop of deterrence that gives countries the confidence to resist bullying,” said Pottinger, who is now a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. “Part of the problem right now is that Beijing has gotten rather arrogant and it’s been less willing to engage productively in diplomacy.”

The announcement of the new security alliance comes as the U.S.-China relationship has deteriorated. Beijing has taken exception to Biden administration officials repeatedly calling out China over human rights abuses in Xianjing province, the crackdown on democracy activists in Hong Kong, and cybersecurity breaches originating from China, as well as Beijing’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic and what the White House has labeled as “coercive and unfair” trade practices.

Even as White House officials have repeatedly spoken out about China, administration officials say they want to work with Beijing on areas of common interest, including curbing the pandemic and climate change.

Biden spoke by phone with China’s President Xi Jinping last week amid growing frustration on the American side that high-level engagement between the two leaders’ top advisers has been largely unfruitful.

After the 90-minute phone call, official Xinhua News Agency reported that Xi expressed concerns that U.S. government policy toward China has caused “serious difficulties” in relations.

Asked Tuesday about media reports that Xi had declined to commit to meet with him in person, the U.S. president said it was “untrue.” Biden did not speak in “specific terms” about the new AUKUS alliance during last week’s call with the Chinese leader, according to the senior administration official.

The U.S. and Australia, along with India and Japan, are members of a strategic dialogue known as “the Quad.” Biden is set to host fellow Quad leaders at the White House next week.

Biden has sought to rally allies to speak with a more unified voice on China and has tried to send the message that he would take a radically different approach to China than former President Donald Trump, who placed trade and economic issues above all else in the U.S.-China relationship.

In June, at Biden’s urging, Group of Seven nations called on China to respect human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang province and to permit a full probe into the origins of COVID-19. While the allies broadly agreed to work toward competing against China, there was less unity on how adversarial a public position the group should take.

President Joe Biden, listens from the East Room of the White House in Washington, on Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021, as he is joined virtually by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, not seen, as he speaks about a national security initiative. (Andrew Harnik/AP)

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden announced Wednesday that the United States is forming a new Indo-Pacific security alliance with Britain and Australia that will allow for greater sharing of defense capabilities — including helping equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines. It’s a move that could deepen a growing chasm in U.S.-China relations.

Biden made the announcement alongside British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who joined him by video to unveil the new alliance, which will be called AUKUS (pronounced AWK-us). The three announced they would quickly turn their attention to developing nuclear-powered submarines for Australia.

“We all recognize the imperative of ensuring peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific over the long term,” said Biden, who said the new alliance reflects a broader trend of key European partners playing a role in the Indo-Pacific. “We need to be able to address both the current strategic environment in the region and how it may evolve.”

None of the leaders mentioned China in their remarks. But the new security alliance is likely to be seen as a provocative move by Beijing, which has repeatedly lashed out at Biden as he’s sought to refocus U.S. foreign policy on the Pacific in the early going of his presidency.

Before the announcement, a senior administration official sought to play down the idea that the alliance was meant to serve as a deterrent against China in the region. The official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to preview the announcement, said the alliance’s creation was not aimed at any one country, and is about a larger effort to sustain engagement and deterrence in the Indo-Pacific by the three nations.

Johnson said the alliance would allow the three English-speaking maritime democracies to strengthen their bonds and sharpen their focus on an increasingly complicated part of the world.

“We will have a new opportunity to reinforce Britain’s place at the leading edge of science and technology, strengthening our national expertise, and perhaps most significant, the U.K., Australia and the U.S. will be joined even more closely together, “ Johnson said.

The three countries have agreed to share information in areas including artificial intelligence, cyber and underwater defense capabilities.

But plans to support Australia acquiring nuclear-powered submarines are certain to catch Beijing’s attention. To date, the only country that the United States has shared nuclear propulsion technology with is Britain. Morrison said Australia is not seeking to develop a nuclear weapons program and information sharing would be limited to helping it develop a submarine fleet.

The Australian prime minister said plans for the nuclear-powered submarines would be developed over the next 18 months and the vessels would be built in Adelaide, Australia.

Australia had announced in 2016 that French company DCNS had beat out bidders from Japan and Germany to build the next generation of submarines in Australia’s largest-ever defense contract.

Top French officials made clear they were unhappy with the deal, which undercuts the DCNS deal.

“The American choice to exclude a European ally and partner such as France from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region, whether in terms of our values or in terms of respect for multilateralism based on the rule of law, shows a lack of coherence that France can only note and regret,” French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and defense minister Florence Parly said in a joint statement.

Morrison said the three countries had “always seen through a similar lens,” but, as the world becomes more complex, “to meet these new challenges, to help deliver the security and stability our region needs, we must now take our partnership to a new level.”

Matt Pottinger, who served as deputy national security adviser in the Trump administration, said that equipping Australia with nuclear-powered submarines was a significant step that would help the U.S. and its allies on the military and diplomatic fronts.

Underwater warfare capabilities have been Beijing’s “Achilles’ heel,” Pottinger said. A nuclear-powered submarine fleet would allow Australia to conduct longer patrols, giving the new alliance a stronger presence in the region.

“When you have a strong military, it provides a backdrop of deterrence that gives countries the confidence to resist bullying,” said Pottinger, who is now a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. “Part of the problem right now is that Beijing has gotten rather arrogant and it’s been less willing to engage productively in diplomacy.”

The announcement of the new security alliance comes as the U.S.-China relationship has deteriorated. Beijing has taken exception to Biden administration officials repeatedly calling out China over human rights abuses in Xianjing province, the crackdown on democracy activists in Hong Kong, and cybersecurity breaches originating from China, as well as Beijing’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic and what the White House has labeled as “coercive and unfair” trade practices.

Even as White House officials have repeatedly spoken out about China, administration officials say they want to work with Beijing on areas of common interest, including curbing the pandemic and climate change.

Biden spoke by phone with China’s President Xi Jinping last week amid growing frustration on the American side that high-level engagement between the two leaders’ top advisers has been largely unfruitful.

After the 90-minute phone call, official Xinhua News Agency reported that Xi expressed concerns that U.S. government policy toward China has caused “serious difficulties” in relations.

Asked Tuesday about media reports that Xi had declined to commit to meet with him in person, the U.S. president said it was “untrue.” Biden did not speak in “specific terms” about the new AUKUS alliance during last week’s call with the Chinese leader, according to the senior administration official.

The U.S. and Australia, along with India and Japan, are members of a strategic dialogue known as “the Quad.” Biden is set to host fellow Quad leaders at the White House next week.

Biden has sought to rally allies to speak with a more unified voice on China and has tried to send the message that he would take a radically different approach to China than former President Donald Trump, who placed trade and economic issues above all else in the U.S.-China relationship.

In June, at Biden’s urging, Group of Seven nations called on China to respect human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang province and to permit a full probe into the origins of COVID-19. While the allies broadly agreed to work toward competing against China, there was less unity on how adversarial a public position the group should take.

Alliance with Australia and US a ‘downpayment on global Britain’

Comment from White House shows there is a price to be paid: support for US-led stronger posture against Beijing

Britain’s post-Brexit foreign policy is taking shape, and the early moves are hardly very surprising: a tripartite defence alliance with the US and Australia – handily compressed to Aukus – clearly designed to send a message to Beijing.

The three start work by sharing with Canberra what is ultimately an American technology: supplying nuclear reactors to power submarines with the likely assistance of Britain’s Rolls-Royce and BAE Systems, a relationship that may also allow the Australians to ditch a troubled but lucrative A$90bn (£48bn) diesel engine agreement with a French contractor.

Australia’s new nuclear-powered submarines will not be nuclear-armed, and the country has no desire to be a nuclear power. But there are questions as to how precisely the enriched uranium required will be supplied and how the reactors will be decommissioned – or to put it another way, what will be done in Australia, the UK or the US. The three will spend the next 18 months trying to work it out.

In theory, it would have been perfectly possible for the US to work directly with their Australian counterparts on the sensitive technology transfer (a development so rare that it has only happened once before in history, when the US helped Britain start its own nuclear submarine programme in late 1958).

But as a senior White House official revealed, it was the UK that wanted this the most. “Great Britain has been a very strong strategic leader in this effort,” said one, speaking ahead of the announcement, helping “mediate and engage on all the critical issues” as the partnership was being thrashed out.

It is a vital endorsement after a tricky summer in which Anglo-American relations have been far from smooth during the Afghanistan crisis. British generals and ministers made little secret that they disagreed with Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw troops from the country, effectively handing it over to the Taliban.

There was a lack of understanding of the tactical intentions of the White House. British sources complained it was unclear when the US would pull out of Kabul airport, and Ben Wallace, the defence secretary, a survivor of Wednesday’s reshuffle, even appeared to question if the US had the will to be a superpower any longer.

Now at least, the prime minister, Boris Johnson, can head over the US for the UN general assembly, and his first White House meeting with Joe Biden, with something else to talk about.

But for the UK there will be a price. What the US president wants is for the UK to be more present in the Indo-Pacific, even though it is thousands of miles away from home. The submarine deal is, the White House official observed, “a downpayment” on the “concept of global Britain”.

In June, Biden came to Europe for his first overseas tour as president, wanting western allies to sign up to a stronger posture against Beijing. Nato, traditionally focused on Russia, obliged and agreed to declare that China also poses a security risk at its annual summit. Yet the White House wants to go further.

The Pentagon has hardly been shy in pointing out that China, which has its own nuclear-powered submarines, now possesses the world’s largest navy. The US has repeatedly wanted allies to help: over the summer Britain’s new Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier participated in muscle-flexing military exercises in the Philippine Sea.

A serious confrontation with China remains unlikely, but this is not the point. With access to European markets not as friction-free as before, the UK is choosing to build a political and industrial strategy based in part on defence and helping longstanding but far-flung allies, starting with supplying nuclear-powered submarines.

Comment from White House shows there is a price to be paid: support for US-led stronger posture against Beijing

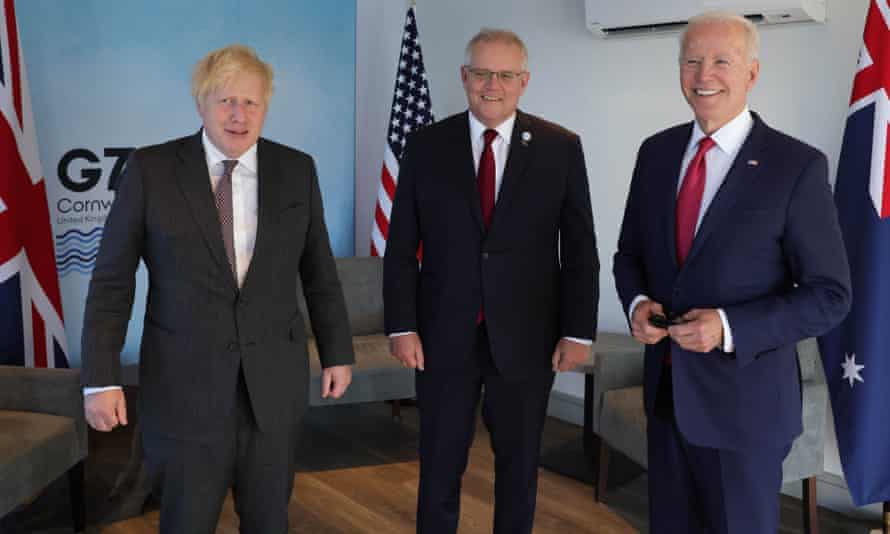

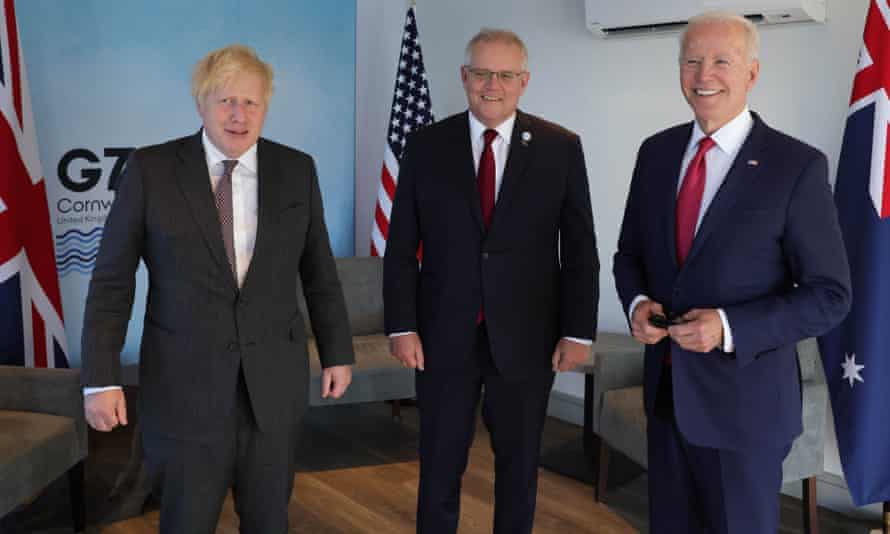

Boris Johnson, the Australian prime minister, Scott Morrison, and the US president, Joe Biden, at the G7 summit in June.

Photograph: Andrew Parsons/UPI/Rex/Shutterstock

Dan Sabbagh

Wed 15 Sep 2021

Dan Sabbagh

Wed 15 Sep 2021

Britain’s post-Brexit foreign policy is taking shape, and the early moves are hardly very surprising: a tripartite defence alliance with the US and Australia – handily compressed to Aukus – clearly designed to send a message to Beijing.

The three start work by sharing with Canberra what is ultimately an American technology: supplying nuclear reactors to power submarines with the likely assistance of Britain’s Rolls-Royce and BAE Systems, a relationship that may also allow the Australians to ditch a troubled but lucrative A$90bn (£48bn) diesel engine agreement with a French contractor.

Australia’s new nuclear-powered submarines will not be nuclear-armed, and the country has no desire to be a nuclear power. But there are questions as to how precisely the enriched uranium required will be supplied and how the reactors will be decommissioned – or to put it another way, what will be done in Australia, the UK or the US. The three will spend the next 18 months trying to work it out.

In theory, it would have been perfectly possible for the US to work directly with their Australian counterparts on the sensitive technology transfer (a development so rare that it has only happened once before in history, when the US helped Britain start its own nuclear submarine programme in late 1958).

But as a senior White House official revealed, it was the UK that wanted this the most. “Great Britain has been a very strong strategic leader in this effort,” said one, speaking ahead of the announcement, helping “mediate and engage on all the critical issues” as the partnership was being thrashed out.

It is a vital endorsement after a tricky summer in which Anglo-American relations have been far from smooth during the Afghanistan crisis. British generals and ministers made little secret that they disagreed with Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw troops from the country, effectively handing it over to the Taliban.

There was a lack of understanding of the tactical intentions of the White House. British sources complained it was unclear when the US would pull out of Kabul airport, and Ben Wallace, the defence secretary, a survivor of Wednesday’s reshuffle, even appeared to question if the US had the will to be a superpower any longer.

Now at least, the prime minister, Boris Johnson, can head over the US for the UN general assembly, and his first White House meeting with Joe Biden, with something else to talk about.

But for the UK there will be a price. What the US president wants is for the UK to be more present in the Indo-Pacific, even though it is thousands of miles away from home. The submarine deal is, the White House official observed, “a downpayment” on the “concept of global Britain”.

In June, Biden came to Europe for his first overseas tour as president, wanting western allies to sign up to a stronger posture against Beijing. Nato, traditionally focused on Russia, obliged and agreed to declare that China also poses a security risk at its annual summit. Yet the White House wants to go further.

The Pentagon has hardly been shy in pointing out that China, which has its own nuclear-powered submarines, now possesses the world’s largest navy. The US has repeatedly wanted allies to help: over the summer Britain’s new Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier participated in muscle-flexing military exercises in the Philippine Sea.

A serious confrontation with China remains unlikely, but this is not the point. With access to European markets not as friction-free as before, the UK is choosing to build a political and industrial strategy based in part on defence and helping longstanding but far-flung allies, starting with supplying nuclear-powered submarines.

‘Stab in the back’: France slams Australia, US over move to ditch €50B submarine deal

‘We had established a trusting relationship with Australia, and this trust was betrayed,’ Foreign Affairs Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian says.

Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian called the decision “contrary to the spirit and letter of the cooperation between France and Australia." | Sia Kambou/AFP via Getty Images

BY JULES DARMANIN AND ZOYA SHEFTALOVICH

September 16, 2021

The French government has hit out Australia's decision to tear up a submarine deal with France worth more than €50 billion to instead acquire American-made nuclear-powered submarines.

"It's a stab in the back. We had established a trusting relationship with Australia, and this trust was betrayed," French Foreign Affairs Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said in a Franceinfo interview Thursday morning. Le Drian added he was "angry and very bitter about this break up," adding that he had spoken to his Australian counterpart days ago and received no serious indication of the move.

Under a deal announced Wednesday by U.S. President Joe Biden, Australia, the U.K. and the U.S. will form a new alliance to be known as AUKUS, which will see the three countries share advanced technologies with one another. As part of the new pact, Canberra will abandon its submarine deal with France.

Le Drian indicated that France would fight the move. “This is not over," he said. "We’re going to need clarifications. We have contracts. The Australians need to tell us how they’re getting out of it. We’re going to need explanation. We have an intergovernmental deal that we signed with great fanfare in 2019, with precise commitments, with clauses, how are they getting out of it? They’re going to have to tell us. So this is not the end of the story."

In a statement released before the interview, Le Drian and Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly said: “This decision is contrary to the letter and spirit of the cooperation that prevailed between France and Australia."

The statement continued: "The American choice to push aside an ally and European partner like France from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region ... shows a lack of consistency France can only note and regret."

The Franco-Australian submarine deal has been significantly troubled for years, with tensions building between French shipbuilder Naval Group and Canberra over cost blowouts, design changes and local industry involvement in the project to build 12 diesel Shortfin Barracuda submarines, announced in April 2016.

‘We had established a trusting relationship with Australia, and this trust was betrayed,’ Foreign Affairs Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian says.

Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian called the decision “contrary to the spirit and letter of the cooperation between France and Australia." | Sia Kambou/AFP via Getty Images

BY JULES DARMANIN AND ZOYA SHEFTALOVICH

September 16, 2021

The French government has hit out Australia's decision to tear up a submarine deal with France worth more than €50 billion to instead acquire American-made nuclear-powered submarines.

"It's a stab in the back. We had established a trusting relationship with Australia, and this trust was betrayed," French Foreign Affairs Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said in a Franceinfo interview Thursday morning. Le Drian added he was "angry and very bitter about this break up," adding that he had spoken to his Australian counterpart days ago and received no serious indication of the move.

Under a deal announced Wednesday by U.S. President Joe Biden, Australia, the U.K. and the U.S. will form a new alliance to be known as AUKUS, which will see the three countries share advanced technologies with one another. As part of the new pact, Canberra will abandon its submarine deal with France.

Le Drian indicated that France would fight the move. “This is not over," he said. "We’re going to need clarifications. We have contracts. The Australians need to tell us how they’re getting out of it. We’re going to need explanation. We have an intergovernmental deal that we signed with great fanfare in 2019, with precise commitments, with clauses, how are they getting out of it? They’re going to have to tell us. So this is not the end of the story."

And he added that the announcement of the move was reminiscent of Biden's predecessor in office, Donald Trump. “What concerns me as well is the American behavior," he said. "This brutal, unilateral, unpredictable decision looks very much like what Mr. Trump used to do … Allies don’t do this to each other … It’s rather insufferable."

In a statement released before the interview, Le Drian and Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly said: “This decision is contrary to the letter and spirit of the cooperation that prevailed between France and Australia."

The statement continued: "The American choice to push aside an ally and European partner like France from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region ... shows a lack of consistency France can only note and regret."

The Franco-Australian submarine deal has been significantly troubled for years, with tensions building between French shipbuilder Naval Group and Canberra over cost blowouts, design changes and local industry involvement in the project to build 12 diesel Shortfin Barracuda submarines, announced in April 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment