LONG READ

In an exclusive excerpt from The Contrarian, a new biography, the disruption-preaching power broker is revealed as just another rich guy desperate to keep his fortune from the IRS.

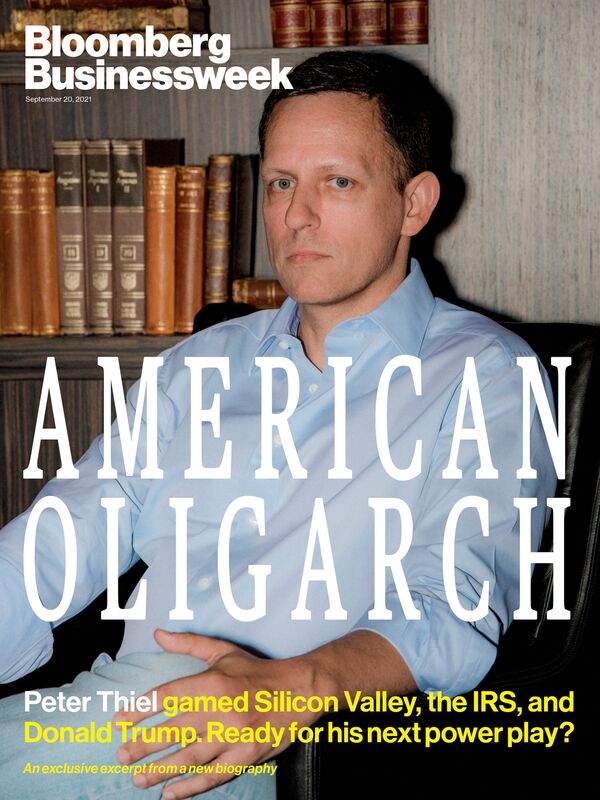

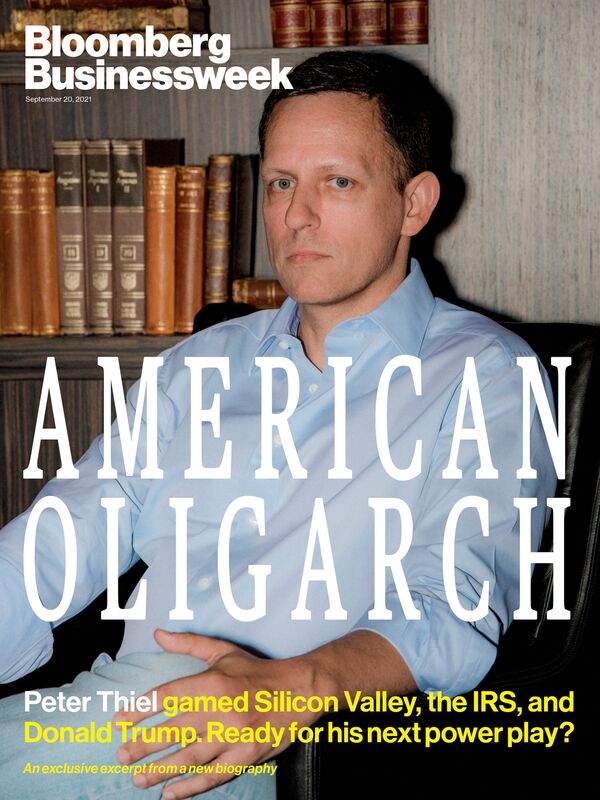

Peter Thiel in 2019.

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: 731; PHOTOGRAPHER: KIYOSHI OTA/BLOOMBERG

By Max Chafkin

September 14, 2021, 10:01 PM MDT

BLOOMBERG BUSINESS WEEK

The meeting started with a thank-you. President-elect Donald Trump was planted at a long table on the 25th floor of his Manhattan tower. Trump sat dead center, per custom, and, also per custom, looked deeply satisfied with himself. He was joined by his usual coterie of lackeys and advisers and, for a change, the heads of the largest technology companies in the world.

“These are monster companies,” Trump declared, beaming at a group that included Apple’s Tim Cook, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, and the chief executives of Google, Cisco, Oracle, Intel, and IBM. Then he acknowledged the meeting’s organizer, Peter Thiel.

Thiel sat next to Trump with his arms tucked under the table, as if trying to shrink away from the president-elect. “I want to start by thanking Peter,” Trump began. “He saw something very early—maybe before we saw it.” Trump reached below the table groping for Thiel’s hand, found it, and raised it. “He’s been so terrific, so outstanding, and he got just about the biggest applause at the Republican National Convention,” he said, patting Thiel’s fist affectionately. “I want to thank you, man. You’re a very special guy.”

Trump and Thiel at Trump Tower on Dec. 14, 2016.

PHOTOGRAPHER: ALBIN LOHR-JONES/BLOOMBERG

The moment of bro tenderness may have been awkward for Thiel, but it was kind of an achievement. Until the Trump Tower meeting, in December 2016, he’d been known as a wealthy and eccentric venture capitalist—a key figure in Silicon Valley for sure, but hardly someone with political clout. His support of Trump, starting in May 2016, when fellow Davos-goers were mostly bedded down with other candidates, had changed that. He’d gotten a prime-time slot at the Republican National Convention, and then, days after the leak of the Access Hollywood tape, in which Trump bragged about sexual assault, kicked in a donation of $1.25 million. Ignore the sexist language, Thiel advised; voters should take Trump “seriously, not literally.” The argument prevailed, and now Thiel was in an enviable position: a power broker between the unconventional leader-elect of the free world and an industry that was said to hate him.

Much had been made during the campaign about the gulf between Silicon Valley and the Republican Party. The Valley favored immigration and tolerance; Trump wanted to build the wall and roll back rights for LGBT Americans. The Valley prized expertise; Trump used his own coarseness as a credential. Pundits had predicted that these differences would be insurmountable—and indeed early accounts of the meeting, based on the four or so minutes during which media were allowed in the room, suggested that this was what had happened. Business Insider published a photo of Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, Google’s Larry Page, and Bezos grimacing under the headline “This Perfectly Captures the First Meeting Between Trump and All the Tech CEOs Who Opposed Him.”

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, Sept. 20, 2021. Subscribe now.

PHOTOGRAPHER: DAMIEN MALONEY/REDUX

But Silicon Valley also reflected the values of the man who’d organized the meeting, and Thiel—a gay immigrant technologist with two Stanford degrees, who’d somehow found his way to becoming a fervent Trump supporter—seemed to value the expansion of his own wealth above almost all else. After the press left, according to notes from the meeting and the accounts of five people familiar with its details, the tech CEOs followed his lead. They were polite, even solicitous, thanking Trump profusely and repeatedly as he cracked wise at their expense. Trump negged Bezos over his ownership of the Washington Post and Cook over Apple’s balance sheet. “Tim has a problem,” Trump said. “He has too much cash.” The CEOs listened politely.

Trump moved on to mass deportations. “We’re going to do a whole thing on immigration,” he said. “We are going to get the bad people.” These were promises that Thiel supported and the tech CEOs ostensibly opposed. Now, in private, no one objected. They implied that it would be fine to crack down on illegal immigrants as long as Trump would be able to supply their companies with enough skilled foreign workers. “We should separate the border security from the talented people,” Cook said. He suggested the U.S. try to cultivate a “monopoly on talent.” Google former Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt, a longtime friend of Thiel’s despite being a major Democratic Party donor, offered a way to brand Trump’s carrot-and-stick approach to immigration reform in a friendlier way. “Call it the U.S. Jobs Act,” he offered. When conversation shifted to China, none of the CEOs urged restraint; many began offering their own gripes.

Years later, Trump’s advisers would point to this moment, crediting Thiel for convincing Silicon Valley that it could work with a president who’d spent the campaign treating them as a bunch of America-hating globalists. “They were supposed to be the biggest enemies we got, and they’re basically making a nationalistic case,” says Steve Bannon, who attended the meeting and served as chief adviser to the White House. “It was like they finally got invited to lunch with the quarterback of the football team.”

The Trump administration, of course, ended badly for many of the participants in the meeting. Bannon was fired the following year, indicted in 2020, and pardoned just hours before Trump himself left the White House, having become the 11th president in U.S. history to lose reelection. He would depart for Mar-a-Lago in disgrace, his legacy tarnished by a pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands, his political future linked to a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

But Trump’s presidency would not end badly for Thiel, who didn’t comment for this article, adapted from my forthcoming book, The Contrarian. Thiel’s companies would win government contracts, and his net worth would soar—and it would, crucially, remain in the legal tax shelter that he’s spent half his career trying to protect. As a venture capitalist, Thiel had made it his business to find up-and-comers, invest in their success, and then sell his stock when it was financially advantageous to do so. Now he was doing the same with a U.S. president.

Thiel speaks at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland on July 21, 2016.

PHOTOGRAPHER: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG

Thiel is sometimes portrayed as the tech industry’s token conservative, a view that wildly understates his power. More than any other living Silicon Valley investor or entrepreneur—more so even than Bezos, or Page, or Facebook co-founder and Thiel protégé Mark Zuckerberg—he has been responsible for creating the ideology that has come to define Silicon Valley today: that technological progress should be pursued relentlessly, with little if any regard for potential costs or dangers to society. Thiel isn’t the richest tech mogul, but he has been, in many ways, the most influential.

His first company, PayPal, pioneered online payments and is now worth more than $300 billion. The data-mining firm Palantir Technologies, his second company, paved the way for what its critics call surveillance capitalism. Later, Palantir became a key player in Trump’s immigration and defense projects. The company is worth around $50 billion; Thiel has been selling stock, but he is still its biggest shareholder.

As impressive as this entrepreneurial résumé might be, Thiel has been even more influential as an investor and backroom dealmaker. He leads the so-called PayPal Mafia, an informal network of interlocking financial and personal relationships that dates to the late 1990s. This group includes Elon Musk, plus the founders of YouTube, Yelp, and LinkedIn; the members would provide startup capital to Airbnb, Lyft, Stripe, and Facebook.

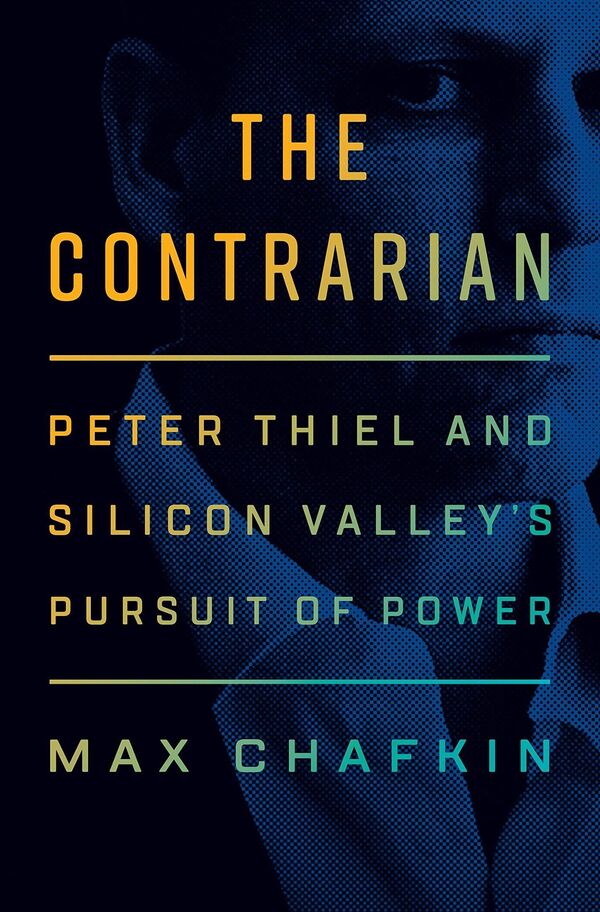

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power by Max Chafkin

The ambitions of these men have often gone hand in hand with Thiel’s extremist libertarian political project: a reorganization of civilization that would shift power from traditional institutions—e.g., mainstream media, democratically elected legislatures—toward startups and the billionaires who control them. Thiel secretly funded the lawsuit that destroyed Gawker Media in 2016. He has also made the case for his political vision in college lectures, in speeches, and in his book Zero to One, which recounts his own personal journey from corporate law washout to dot-com billionaire. The success manual argues that monopolies are good, monarchies efficient, and tech founders godlike. It has sold around 3 million copies worldwide.

For the young people who buy his books, watch and rewatch his talks, and write social media odes to his genius, Thiel is like Ayn Rand crossed with one of her fictional characters. He’s a libertarian philosopher and a builder—Howard Roark with a YouTube following. His most avid acolytes become Thiel Fellows, accepting $100,000 to drop out of school; others take jobs within his circle of advisers, whom he supports financially and who promote and defend him and his ideas.

On election night in 2016, a group of 20 or so of these loyalists, including entrepreneurs and investors, joined Thiel at his enormous home in San Francisco to watch the returns come in. “You’re never totally sure,” Thiel declaimed to his courtiers, as Fox News showed returns from Wisconsin and Michigan. “But he had all these elements.” Trump “was silly enough to get all this attention,” Thiel continued. “He was just serious enough to actually do it.”

Thiel’s phone was already ringing, and his aides were discussing their prospects. Thiel was going to be named as a member of the transition’s executive committee in a matter of days, they figured, and Trump would give him a substantial portfolio. “The conversation,” says someone who attended the party, “was basically, ‘Where do you want to work?’ ”

A week later, Thiel reported to Trump Tower with a half-dozen aides. They were Thiel’s type: young, smart, and attractive. “They looked like male models,” Bannon recalls. The group, led by Blake Masters, a longtime aide who’d served as Thiel’s Zero to One co-writer, was given the job of suggesting appointees who could drastically limit the scope of “the administrative state.”

Thiel wasn’t playing for influence. He was playing for money

As a political animal, Thiel possessed instincts that could seem almost comically bad. His list of 150 names for senior-level jobs included numerous figures who were too extreme even for the most extreme members of Trump’s inner circle. Many were ultra-libertarians or reactionaries; others were more difficult to categorize. “Peter’s idea of disrupting government is out there,” Bannon says. “People thought Trump was a disrupter. They had no earthly idea.”

For Trump’s science adviser, Thiel suggested two climate change deniers, Princeton physicist William Happer and Yale computer scientist David Gelernter. For the head of the Food and Drug Administration, Thiel offered, among other names, Balaji Srinivasan, an entrepreneur with no obvious experience in government, who seemed skeptical that the FDA should exist at all. “For every thalidomide,” Srinivasan had tweeted (and later deleted), “many dead from slowed approvals.”

Bannon brought them all to meet with Trump but didn’t endorse the picks. “Balaji is a genius,” he says. “But it was too much.” Bannon knew it was unrealistic to nominate a provocateur who’d implied he wanted to get rid of the FDA to run said agency. Doing so would have gotten Trump branded a radical—and not the good kind. Bannon continues, “That’s not a confirmation hearing you’re going to win in the first 100 days. Remember, we’re a coalition, and the Republican establishment was aghast at what we were doing.”

Srinivasan and Gelernter did not respond to requests for comment. Happer praises Thiel for his “refusal to be cowed by political correctness” but adds, “I never thought of Peter as very strong in technology, unless you narrow down the definition of technology to ways to profit from the internet.” In 2018, Trump appointed Happer to a lesser position as senior director for emerging technologies at the National Security Council. He left the administration in 2019, complaining that he’d been undermined by White House officials who’d been “brainwashed” into believing in the dangers of climate change.

In the end Thiel managed to install only a dozen or so allies in the White House, and he lost his most important connection to Trump with Bannon’s departure the following August. According to a person who worked on the transition who asked to remain anonymous to avoid angering Thiel or Trump, Thiel and Masters “basically allied themselves with the alt-right. They chose disruption over normalcy, and it backfired.” That, of course, assumed that Thiel’s goals were only political. But many who have worked closely with him say that assessment is wrong; Thiel wasn’t playing for influence. He was playing for money.

Thiel and Musk display their corporate credit cards at PayPal headquarters in Palo Alto, Calif., in October 2000.

PHOTOGRAPHER: PAUL SAKUMA/AP PHOTO

Invites to that Trump Tower meeting had been given out to the tech companies with the largest market capitalizations, but Thiel made two exceptions. Musk, who runs SpaceX, where Thiel is a major shareholder, got to come even though both SpaceX and his other company, Tesla, were much smaller than the next largest company at the time. So did Alex Karp, CEO of an even smaller company, Palantir, which Thiel had co-founded in 2004.

Palantir had originally been an attempt to sell the U.S. government on data-mining technology developed at PayPal. The company, which was seeded by Thiel and received funding from the CIA, cultivated a cloak-and-dagger reputation, encouraging reporters to write stories that presented its technology as an all-seeing orb, like the fictional Palantir in The Lord of the Rings, for which Thiel had named it. “I’d rather be seen as evil than incompetent,” Thiel explained to a friend when asked about the company’s marketing strategy.

But inside Palantir there were questions about to what extent—or even whether—the technology worked. The company had struggled during President Barack Obama’s second term as enthusiasm for its offerings dimmed among intelligence agencies and big corporate customers. Palantir had hoped to compete for a contract with the U.S. Army, which was developing a new database system, but the Army seemed inclined to work with traditional defense contractors instead, effectively freezing Thiel out of hundreds of millions of dollars a year in revenue. “It was very shaky ground,” says Alfredas Chmieliauskas, who was hired by Palantir in 2013 to do business development in Europe. “We had nothing.” Another senior executive called Metropolis, Palantir’s main product, a “disaster.”

It had been this sense of desperation that led Chmieliauskas to begin cultivating Cambridge Analytica, a British political consulting firm, backed by Bannon and hedge fund manager Robert Mercer, that aimed to create psychographic profiles of voters using social media data. In 2014, Chmieliauskas, who saw the company as a potential client, suggested that it create an app to scrape Facebook data. Cambridge Analytica never became a Palantir customer, but it took Chmieliauskas’s suggestion and ran with it, eventually accessing the Facebook data of 87 million people without their knowledge.

Palantir would claim that Chmieliauskas had been a rogue employee acting on his own when he suggested the idea. Chmieliauskas says that’s misleading; he says his bosses knew what he was up to and in fact encouraged him to pursue business that was ethically dubious. “They threw me under the bus,” he says. “I’d worked on much shadier deals before Cambridge Analytica.” A Palantir spokeswoman declined to comment. Cambridge Analytica, which denied wrongdoing, went out of business in 2018.

In any case, the new administration presented an opportunity for Palantir—and for Thiel, who had much of his net worth tied up in the company. Just before Election Day in 2016, a federal judge had ruled in a lawsuit brought by Palantir that the Army would have to rebid its database contract and consider Thiel’s company. The court order didn’t mean the Army would buy Palantir’s software, only that it would give it a “hard look,” as Hamish Hume, the company’s lawyer on the case, put it.

Now Karp (and Thiel) had a chance to make a personal appeal to the commander in chief. During the meeting at Trump Tower, Karp promised Trump that Palantir could “help bolster national security and reduce waste.” Karp would later say he had no idea why he’d been invited; all he knew was that his friend had organized it. Of course, Thiel didn’t invite any other defense contractors, such as Raytheon Technologies, Palantir’s main competitor in the bidding on the Army deal, to the meeting.

“Peter’s idea of disrupting government is out there,” Bannon says. “People thought Trump was a disrupter. They had no earthly idea”

Thiel would seem to push the government toward Palantir in other ways. He urged Trump to fire Francis Collins, the longtime director of the National Institutes of Health and an accomplished geneticist who’d headed up the Human Genome Project under Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. This had implications for Palantir, which would have considered the NIH, a massive user of data, a ripe target for its salespeople. Thiel argued that the NIH needed shaking up and suggested that Collins be replaced with Andy Harris, a Republican congressman from Maryland’s rural Eastern Shore and a member of the far-right House Freedom Caucus.

Bannon resisted the effort but agreed to have Collins come to New York in early January to interview for his current job. The agenda included a lunch with Thiel and Masters. In a follow-up email afterward, according to documents that were later made public through a Freedom of Information Act request by independent journalist Andrew Granato, Collins mentioned an eagerness to learn more about Palantir. He said he was meeting with Palantir’s top business development executive. It appears, in retrospect, to have been the beginning of a very successful sales pitch. Collins would be reappointed, and, the following year, the NIH would give Palantir a $7 million contract to help the agency keep track of the research data it was collecting. There would be many more contracts.

Thiel may not have been entirely successful in his push to install loyalists inside the Trump White House, but he didn’t entirely fail either. Michael Kratsios, his former chief of staff, joined the administration as the U.S. chief technology officer and would later become an acting undersecretary of defense, in charge of the Pentagon’s research and development budget. Kevin Harrington, a longtime Thiel adviser, accepted a senior position on the National Security Council. Several others with connections to Thiel would also take senior defense jobs, including Michael Anton, a friend and conservative firebrand—he’d written an essay, “The Flight 93 Election,” that made an intellectual case for Trump—and Justin Mikolay, a former Palantir marketer, who joined the Department of Defense as a speechwriter for Secretary of Defense James Mattis. Mattis’s deputy chief of staff, Anthony DeMartino, and senior adviser, Sally Donnelly, had also done work for Palantir as consultants.

It’s possible, of course, that the appointment of military officials sympathetic to Palantir’s brand of disruption had nothing to do with Thiel—these ideas were gaining currency in government circles even during the Obama administration, and in interviews, Palantir executives emphatically said they had not benefited from preferential treatment. “It’s completely and utterly ludicrous,” Karp said, when I asked him about Palantir’s Trump-era success during a 2019 interview. “It takes 10 years to build this kind of business.”

Ultimately the Army held a bake-off between Palantir and Raytheon for the disputed contract, in which each company was asked to build a prototype system and present it to a panel of soldiers. It was exactly the kind of contest Palantir had called for in a lawsuit a few years prior. Some Palantir insiders wondered if the Pentagon’s leadership had been convinced on the merits—Palantir’s software had indeed improved a lot over the previous few years—or if political pressure had been brought to bear by Thiel and his allies. Either way, in early 2019, the Army announced that Palantir had won outright: The company would get its largest contract ever, worth $800 million or more. The win created momentum, with the company suddenly in the hunt for more Pentagon business.

In 2019, Palantir took over $40 million a year in contracts for Project Maven, a Defense Department effort to use artificial intelligence software to analyze drone footage. That happened despite Palantir’s limited experience in the kind of image-recognition software that Maven used to identify targets—and despite concerns from a government official expressed in an anonymous memo sent to military brass, and first reported by the New York Times, that the company had received preferential treatment in landing the contract. There would be another huge Army contract, announced in December, worth as much as $440 million over four years, plus $10 million from Trump’s brand-new military branch, the Space Force, and $80 million from the Navy. And Palantir ignored the objections of its own employees and immigration activists, renewing its contract with Trump’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency for another $50 million or so.

As the ICE contract showed, Thiel wasn’t above directly linking his business interests with Trump’s most extreme policies. In 2017, Charles Johnson, a longtime Thiel confidant who’d maintained close ties to members of the alt-right, pitched Thiel to invest in a new venture called Clearview AI. The idea, as Johnson explained, was simple: He and an engineer had written software to scrape as many photos as possible from Facebook and other social networks. The software stored the massive trove, along with user names. They would offer this database to police departments and other law enforcement groups, along with a facial recognition algorithm. These tools would allow police to take a picture of an unidentified suspect, upload it into the software, and get a name back.

At the time, Johnson boasted that this technology would be ideal for Trump’s immigration crackdown. “Building algorithms to ID all the illegal immigrants for the deportation squads” was how he put it in a Facebook post. “It was a joke,” says Johnson, who has since cut ties with the alt-right and become a Joe Biden supporter. “But it became real.” Indeed, Clearview would eventually sign a contract to give ICE access to its technology. It would also get Thiel’s help. After hearing Johnson’s pitch, he provided $200,000 in seed capital to the effort. Clearview would land contracts with ICE, the FBI, and numerous federal agencies. Another Thiel-backed contractor, Anduril Industries, capitalized on Trump’s “build the wall” fervor to win a series of contracts with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to contribute digital surveillance technologies, which the company described as a “virtual wall.” Anduril, named after Aragorn’s sword in The Lord of the Rings, is now valued at more than $4 billion.

By the fall of 2020, published estimates were putting Thiel’s personal net worth at around $5 billion, roughly double what it had been before Trump was elected. This was a reflection of his stake in Palantir, which had gone public in August at a valuation of around $20 billion. Thiel then owned about 20% of the company and also held stakes in a number of others whose fortunes had soared. Besides Anduril, there was SpaceX, which was now worth as much as $100 billion thanks in part to a booming business with the federal government, and Airbnb, which had recently gone public. By any financial measure, it had been a good four years.

But those who know Thiel say that even these estimates were probably way too conservative and that his true net worth was closer to $10 billion, possibly much more. That was partly because he had quietly accumulated stakes in a handful of private companies with exceedingly high valuations, including the online payments startup Stripe; a person close to Thiel figures his share is worth at least $1.5 billion. But it was also because Thiel was shielding a large percentage of his investment assets from taxes of any kind.

The strategy was legal, even if it was, from the standpoint of any normal sense of fairness, outrageous. Thiel had parked much of his wealth inside an investment vehicle known as a Roth IRA. Roths are tax-free retirement accounts that were designed for middle-class and lower-middle-class workers, not billionaires—contributions are capped at just $6,000 per year. (You can also convert a traditional IRA into a Roth if you pay taxes on the old account.) It’s illegal to use a Roth account to buy stock in a company you control. And yet, starting in 1999, Thiel used a Roth to buy stock in companies with which he was closely associated—including PayPal and Palantir—for prices that were as low as a thousandth of a penny per share. All the capital gains since then have been tax-free.

The maneuver hinged on an extremely narrow interpretation of what it means to control a company. Thiel didn’t own more than 50% of PayPal at the time of the Roth investment and thus, legally speaking, didn’t control PayPal. But in practice, Thiel had the final say on everything the company did during much of its early history. At one point, in 2001, he threatened to resign as CEO unless the nominally independent board of directors issued him millions of shares. The board agreed because, according to three people familiar with the negotiations, it had no choice; Thiel’s resignation would have killed the company. “It was pay me or I’m going to shoot myself,” recalls one of the people. The board issued almost 4.5 million shares for Thiel to purchase, lending him the money for the transaction. Roughly a third of those shares were bought by Thiel’s Roth IRA. Within a year the new block of shares would be worth $21 million. Thiel would also use the Roth to buy shares in Palantir, whose board was packed with close friends and allies. By the end of 2019, Thiel’s Roth alone was worth $5 billion according to ProPublica, which received leaked copies of Thiel’s tax returns. Four people familiar with Thiel’s finances confirmed the report. Given the performance of the market since then, it’s likely the portfolio is much larger today.

The size of the nest egg, and the aggressive tax strategy Thiel had employed to protect it, put him in a precarious position. According to IRS rules, if a Roth IRA account holder engages in a prohibited transaction—like using the money to invest in a company you legally control—then that person loses the tax break for the entirety of the portfolio’s value. In Thiel’s case that would mean he could be on the hook for a tax bill in the billions. Moreover, in 2014, the Government Accountability Office announced that it had identified 314 taxpayers with IRA balances of more than $25 million, specifically mentioning “founders of companies who use IRAs to invest in nonpublicly traded shares of their newly formed companies”—that is, people who’d done exactly what Thiel did at PayPal and Palantir. The report noted that the IRS planned to investigate these holdings and recommended that Congress pass laws to crack down on the practice. Separately, U.S. tax authorities began an audit of Thiel’s retirement savings.

Thiel was never sanctioned—the audit never turned up anything illegal, according to a person who discussed it with Thiel—but it seemed to make him paranoid. All it would take would be a change in the way the IRS interpreted the rules to force him to pay taxes on the entire Roth account. Or a disgruntled former partner or employee might draw attention to the extent to which Thiel exercised influence over his companies in a way that made it sound like control. “If he violates a single rule, puts a toe in the wrong direction, the government can tax the whole thing,” says another person familiar with the arrangement.

This was scary to Thiel, according to several longtime employees. They say his vulnerability to a change in tax policy or a shift in IRS enforcement seemed to dominate how he related to people around him. Anxiety about a potential crackdown seemed to be part of his motivation to acquire New Zealand citizenship in 2011 and to support Trump in 2016, according to these sources. Now, in 2020, Trump’s reelection prospects were dimming. That left Thiel walking a fine line, staying far enough away from Trump so as not to be blamed if he lost but still close enough to influence Trump’s followers. He never endorsed Trump in 2020, but he was also careful not to criticize the candidate publicly.

Privately he’d taken to referring to Trump’s White House as “the S.S. Minnow”—the hapless fishing charter that runs aground in the show Gilligan’s Island. Of course, in this analogy, Trump was the skipper. There were, as Thiel told a friend in a text, “lots of Gilligans.” In an unrelated nautical metaphor, Thiel said that changes to Trump’s campaign were the equivalent of “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.” Similar comments leaked to the press, which reported that he was souring on Trump because of the administration’s failure to adequately respond to the coronavirus pandemic. But this wasn’t true. Thiel supported Trump on Covid-19, telling friends he thought the lockdowns in states led by Democratic governors were “crazy” and overly broad.

Nor was Thiel or his inner circle moderating. After Trump’s Supreme Court pick, Neil Gorsuch, sided with liberals and moderates in ruling that gay and transgender workers were deserving of civil rights protections, Masters, the Thiel adviser who’d served on the transition, complained that the party had betrayed conservatives. He wrote on Twitter, sardonically, that the point of the Republican Party seemed to be, among other things, “to protect private equity, low taxes, free pornography.”

After Trump’s loss in November, Thiel’s employees and allies were abuzz with rumors about secret uncounted votes in key swing states and how the election’s outcome was somehow in doubt. Eric Weinstein, a podcast host and longtime Thiel adviser, tweeted videos of a purported Postal Service whistleblower. (The claims, which turned out to have been fabricated, were distributed by conservative journalist and provocateur James O’Keefe, another Thiel ally who has received funds from him in the past.) Masters, meanwhile, tweeted darkly about Dominion Voting Systems, amplifying a conspiracy theory alleging that the manufacturer of electronic voting machines had somehow tampered with the results. He also claimed, offering no evidence, that dead people had voted in Milwaukee and Detroit.

In March a newly created political action committee announced that Thiel had pledged a $10 million donation to support the potential Senate candidacy of J.D. Vance, author of the memoir Hillbilly Elegy. Vance worked for Mithril Capital Management, another of Thiel’s venture capital firms, this one named after the magically light metal in The Lord of the Rings. Not long after Hillbilly Elegy came out, Vance moved to Ohio and began plotting a political career. He also started a new Thiel-backed fund focused on investing in Midwestern startups called Narya Capital Management—“Narya” being Elvish for “ring of fire” in The Lord of the Rings.

Vance had once been a critic of Trump. “Fellow Christians, everyone is watching us when we apologize for this man,” he’d tweeted after the infamous Access Hollywood tape leaked. “Lord help us.” But a week before the announcement that Thiel was backing his Senate candidacy, Vance appeared on America First, the podcast run by former Trump adviser Sebastian Gorka, and proclaimed himself a convert to Trump’s Make America Great Again movement. He said that he’d come to agree with Trump’s assessment of what he called “the American Elite.” Vance proclaimed, “They don’t care about the country that has made them who they are.” Then he met with Thiel and Trump at Mar-a-Lago. He deleted his old #nevertrump posts.

In July, Vance, a graduate of Yale Law School, made his run official, railing against universities, anti-American business leaders, “woke” hedge funds, and “Fauci’s cabal” (a reference to Covid restrictions). He proposed cracking down on immigration, curbing China’s rise, and breaking up big tech companies for censoring conservative speech—all positions Thiel had been pushing. Days later, Vance appeared on Fox News and launched an attack on Google, a competitor to Palantir for government contracts. “Google, right now, is actively conspiring with and working with the Chinese government,” Vance said. This charge was spurious and almost identical to one Thiel had made two years earlier at the National Conservatism Conference, where Vance also spoke. At that event, Thiel accused Google, without evidence, of being “treasonous” for failing to work more closely with the Defense Department and for doing business in China.

Masters, meanwhile, announced his own run for Senate in Arizona, proving himself a capable advocate for Thiel, who made another $10 million commitment to his candidacy. Like Vance’s, the Masters platform reads like an extension of Thiel’s worldview, combining Trump-style immigration politics (“Obviously this works,” he said in a video shot at a section of the border wall), complaints about diversity efforts, and plans to rein in tech companies, especially ones in which Thiel doesn’t have an interest. His Thiel-backed PAC recently aired an advertisement attacking a fellow candidate, Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, for refusing to overturn the state’s 2020 election results.

If they win their primaries, and if Republicans win control of the Senate in 2022, Masters and Vance—along with the other two populist nationalists who have received substantial support from Thiel, Josh Hawley of Missouri and Ted Cruz of Texas—would arguably offer Thiel a level of influence greater than what he enjoyed under Trump. A Republican-controlled Senate, especially one where Thiel’s politics are ascendant, would also be ideal for Thiel’s government contractors and for protecting the tax-advantaged status of his Roth IRA.

But Masters and Vance offer more than Trump because, unlike the former president, they’re highly disciplined ideologues who seem committed to popularizing their patron’s political agenda. They are, in other words, as out there as Thiel is. Even better, Masters and Vance both work for Thiel, and not just in the sense that his PAC is paying for TV advertising on their behalf. Masters remains chief operating officer of Thiel Capital and president of the Thiel Foundation; Thiel is a key investor in Narya, Vance’s investment firm. Vance and Thiel recently invested in Rumble, a YouTube competitor that caters to Trumpist talking heads, such as the talk show host Dan Bongino, New York Representative Elise Stefanik, and the former president himself.

Thiel is said to be in the market for other candidates ahead of the midterms and the 2024 election. “He has not reverted back to Republicanism,” Bannon says. “He’s full MAGA.” It’s not clear that Trump’s old slogan has much political salience anymore, but if Silicon Valley’s most influential venture capitalist succeeds in appropriating Trumpism, that would, at the very least, keep America great for Peter Thiel.

From The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power by Max Chafkin, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright 2021 by Max Chafkin.

Peter Thiel in 2019.

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: 731; PHOTOGRAPHER: KIYOSHI OTA/BLOOMBERG

By Max Chafkin

September 14, 2021, 10:01 PM MDT

BLOOMBERG BUSINESS WEEK

The meeting started with a thank-you. President-elect Donald Trump was planted at a long table on the 25th floor of his Manhattan tower. Trump sat dead center, per custom, and, also per custom, looked deeply satisfied with himself. He was joined by his usual coterie of lackeys and advisers and, for a change, the heads of the largest technology companies in the world.

“These are monster companies,” Trump declared, beaming at a group that included Apple’s Tim Cook, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, and the chief executives of Google, Cisco, Oracle, Intel, and IBM. Then he acknowledged the meeting’s organizer, Peter Thiel.

Thiel sat next to Trump with his arms tucked under the table, as if trying to shrink away from the president-elect. “I want to start by thanking Peter,” Trump began. “He saw something very early—maybe before we saw it.” Trump reached below the table groping for Thiel’s hand, found it, and raised it. “He’s been so terrific, so outstanding, and he got just about the biggest applause at the Republican National Convention,” he said, patting Thiel’s fist affectionately. “I want to thank you, man. You’re a very special guy.”

Trump and Thiel at Trump Tower on Dec. 14, 2016.

PHOTOGRAPHER: ALBIN LOHR-JONES/BLOOMBERG

The moment of bro tenderness may have been awkward for Thiel, but it was kind of an achievement. Until the Trump Tower meeting, in December 2016, he’d been known as a wealthy and eccentric venture capitalist—a key figure in Silicon Valley for sure, but hardly someone with political clout. His support of Trump, starting in May 2016, when fellow Davos-goers were mostly bedded down with other candidates, had changed that. He’d gotten a prime-time slot at the Republican National Convention, and then, days after the leak of the Access Hollywood tape, in which Trump bragged about sexual assault, kicked in a donation of $1.25 million. Ignore the sexist language, Thiel advised; voters should take Trump “seriously, not literally.” The argument prevailed, and now Thiel was in an enviable position: a power broker between the unconventional leader-elect of the free world and an industry that was said to hate him.

Much had been made during the campaign about the gulf between Silicon Valley and the Republican Party. The Valley favored immigration and tolerance; Trump wanted to build the wall and roll back rights for LGBT Americans. The Valley prized expertise; Trump used his own coarseness as a credential. Pundits had predicted that these differences would be insurmountable—and indeed early accounts of the meeting, based on the four or so minutes during which media were allowed in the room, suggested that this was what had happened. Business Insider published a photo of Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, Google’s Larry Page, and Bezos grimacing under the headline “This Perfectly Captures the First Meeting Between Trump and All the Tech CEOs Who Opposed Him.”

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, Sept. 20, 2021. Subscribe now.

PHOTOGRAPHER: DAMIEN MALONEY/REDUX

But Silicon Valley also reflected the values of the man who’d organized the meeting, and Thiel—a gay immigrant technologist with two Stanford degrees, who’d somehow found his way to becoming a fervent Trump supporter—seemed to value the expansion of his own wealth above almost all else. After the press left, according to notes from the meeting and the accounts of five people familiar with its details, the tech CEOs followed his lead. They were polite, even solicitous, thanking Trump profusely and repeatedly as he cracked wise at their expense. Trump negged Bezos over his ownership of the Washington Post and Cook over Apple’s balance sheet. “Tim has a problem,” Trump said. “He has too much cash.” The CEOs listened politely.

Trump moved on to mass deportations. “We’re going to do a whole thing on immigration,” he said. “We are going to get the bad people.” These were promises that Thiel supported and the tech CEOs ostensibly opposed. Now, in private, no one objected. They implied that it would be fine to crack down on illegal immigrants as long as Trump would be able to supply their companies with enough skilled foreign workers. “We should separate the border security from the talented people,” Cook said. He suggested the U.S. try to cultivate a “monopoly on talent.” Google former Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt, a longtime friend of Thiel’s despite being a major Democratic Party donor, offered a way to brand Trump’s carrot-and-stick approach to immigration reform in a friendlier way. “Call it the U.S. Jobs Act,” he offered. When conversation shifted to China, none of the CEOs urged restraint; many began offering their own gripes.

Years later, Trump’s advisers would point to this moment, crediting Thiel for convincing Silicon Valley that it could work with a president who’d spent the campaign treating them as a bunch of America-hating globalists. “They were supposed to be the biggest enemies we got, and they’re basically making a nationalistic case,” says Steve Bannon, who attended the meeting and served as chief adviser to the White House. “It was like they finally got invited to lunch with the quarterback of the football team.”

The Trump administration, of course, ended badly for many of the participants in the meeting. Bannon was fired the following year, indicted in 2020, and pardoned just hours before Trump himself left the White House, having become the 11th president in U.S. history to lose reelection. He would depart for Mar-a-Lago in disgrace, his legacy tarnished by a pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands, his political future linked to a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

But Trump’s presidency would not end badly for Thiel, who didn’t comment for this article, adapted from my forthcoming book, The Contrarian. Thiel’s companies would win government contracts, and his net worth would soar—and it would, crucially, remain in the legal tax shelter that he’s spent half his career trying to protect. As a venture capitalist, Thiel had made it his business to find up-and-comers, invest in their success, and then sell his stock when it was financially advantageous to do so. Now he was doing the same with a U.S. president.

Thiel speaks at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland on July 21, 2016.

PHOTOGRAPHER: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG

Thiel is sometimes portrayed as the tech industry’s token conservative, a view that wildly understates his power. More than any other living Silicon Valley investor or entrepreneur—more so even than Bezos, or Page, or Facebook co-founder and Thiel protégé Mark Zuckerberg—he has been responsible for creating the ideology that has come to define Silicon Valley today: that technological progress should be pursued relentlessly, with little if any regard for potential costs or dangers to society. Thiel isn’t the richest tech mogul, but he has been, in many ways, the most influential.

His first company, PayPal, pioneered online payments and is now worth more than $300 billion. The data-mining firm Palantir Technologies, his second company, paved the way for what its critics call surveillance capitalism. Later, Palantir became a key player in Trump’s immigration and defense projects. The company is worth around $50 billion; Thiel has been selling stock, but he is still its biggest shareholder.

As impressive as this entrepreneurial résumé might be, Thiel has been even more influential as an investor and backroom dealmaker. He leads the so-called PayPal Mafia, an informal network of interlocking financial and personal relationships that dates to the late 1990s. This group includes Elon Musk, plus the founders of YouTube, Yelp, and LinkedIn; the members would provide startup capital to Airbnb, Lyft, Stripe, and Facebook.

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power by Max Chafkin

The ambitions of these men have often gone hand in hand with Thiel’s extremist libertarian political project: a reorganization of civilization that would shift power from traditional institutions—e.g., mainstream media, democratically elected legislatures—toward startups and the billionaires who control them. Thiel secretly funded the lawsuit that destroyed Gawker Media in 2016. He has also made the case for his political vision in college lectures, in speeches, and in his book Zero to One, which recounts his own personal journey from corporate law washout to dot-com billionaire. The success manual argues that monopolies are good, monarchies efficient, and tech founders godlike. It has sold around 3 million copies worldwide.

For the young people who buy his books, watch and rewatch his talks, and write social media odes to his genius, Thiel is like Ayn Rand crossed with one of her fictional characters. He’s a libertarian philosopher and a builder—Howard Roark with a YouTube following. His most avid acolytes become Thiel Fellows, accepting $100,000 to drop out of school; others take jobs within his circle of advisers, whom he supports financially and who promote and defend him and his ideas.

On election night in 2016, a group of 20 or so of these loyalists, including entrepreneurs and investors, joined Thiel at his enormous home in San Francisco to watch the returns come in. “You’re never totally sure,” Thiel declaimed to his courtiers, as Fox News showed returns from Wisconsin and Michigan. “But he had all these elements.” Trump “was silly enough to get all this attention,” Thiel continued. “He was just serious enough to actually do it.”

Thiel’s phone was already ringing, and his aides were discussing their prospects. Thiel was going to be named as a member of the transition’s executive committee in a matter of days, they figured, and Trump would give him a substantial portfolio. “The conversation,” says someone who attended the party, “was basically, ‘Where do you want to work?’ ”

A week later, Thiel reported to Trump Tower with a half-dozen aides. They were Thiel’s type: young, smart, and attractive. “They looked like male models,” Bannon recalls. The group, led by Blake Masters, a longtime aide who’d served as Thiel’s Zero to One co-writer, was given the job of suggesting appointees who could drastically limit the scope of “the administrative state.”

Thiel wasn’t playing for influence. He was playing for money

As a political animal, Thiel possessed instincts that could seem almost comically bad. His list of 150 names for senior-level jobs included numerous figures who were too extreme even for the most extreme members of Trump’s inner circle. Many were ultra-libertarians or reactionaries; others were more difficult to categorize. “Peter’s idea of disrupting government is out there,” Bannon says. “People thought Trump was a disrupter. They had no earthly idea.”

For Trump’s science adviser, Thiel suggested two climate change deniers, Princeton physicist William Happer and Yale computer scientist David Gelernter. For the head of the Food and Drug Administration, Thiel offered, among other names, Balaji Srinivasan, an entrepreneur with no obvious experience in government, who seemed skeptical that the FDA should exist at all. “For every thalidomide,” Srinivasan had tweeted (and later deleted), “many dead from slowed approvals.”

Bannon brought them all to meet with Trump but didn’t endorse the picks. “Balaji is a genius,” he says. “But it was too much.” Bannon knew it was unrealistic to nominate a provocateur who’d implied he wanted to get rid of the FDA to run said agency. Doing so would have gotten Trump branded a radical—and not the good kind. Bannon continues, “That’s not a confirmation hearing you’re going to win in the first 100 days. Remember, we’re a coalition, and the Republican establishment was aghast at what we were doing.”

Srinivasan and Gelernter did not respond to requests for comment. Happer praises Thiel for his “refusal to be cowed by political correctness” but adds, “I never thought of Peter as very strong in technology, unless you narrow down the definition of technology to ways to profit from the internet.” In 2018, Trump appointed Happer to a lesser position as senior director for emerging technologies at the National Security Council. He left the administration in 2019, complaining that he’d been undermined by White House officials who’d been “brainwashed” into believing in the dangers of climate change.

In the end Thiel managed to install only a dozen or so allies in the White House, and he lost his most important connection to Trump with Bannon’s departure the following August. According to a person who worked on the transition who asked to remain anonymous to avoid angering Thiel or Trump, Thiel and Masters “basically allied themselves with the alt-right. They chose disruption over normalcy, and it backfired.” That, of course, assumed that Thiel’s goals were only political. But many who have worked closely with him say that assessment is wrong; Thiel wasn’t playing for influence. He was playing for money.

Thiel and Musk display their corporate credit cards at PayPal headquarters in Palo Alto, Calif., in October 2000.

PHOTOGRAPHER: PAUL SAKUMA/AP PHOTO

Invites to that Trump Tower meeting had been given out to the tech companies with the largest market capitalizations, but Thiel made two exceptions. Musk, who runs SpaceX, where Thiel is a major shareholder, got to come even though both SpaceX and his other company, Tesla, were much smaller than the next largest company at the time. So did Alex Karp, CEO of an even smaller company, Palantir, which Thiel had co-founded in 2004.

Palantir had originally been an attempt to sell the U.S. government on data-mining technology developed at PayPal. The company, which was seeded by Thiel and received funding from the CIA, cultivated a cloak-and-dagger reputation, encouraging reporters to write stories that presented its technology as an all-seeing orb, like the fictional Palantir in The Lord of the Rings, for which Thiel had named it. “I’d rather be seen as evil than incompetent,” Thiel explained to a friend when asked about the company’s marketing strategy.

But inside Palantir there were questions about to what extent—or even whether—the technology worked. The company had struggled during President Barack Obama’s second term as enthusiasm for its offerings dimmed among intelligence agencies and big corporate customers. Palantir had hoped to compete for a contract with the U.S. Army, which was developing a new database system, but the Army seemed inclined to work with traditional defense contractors instead, effectively freezing Thiel out of hundreds of millions of dollars a year in revenue. “It was very shaky ground,” says Alfredas Chmieliauskas, who was hired by Palantir in 2013 to do business development in Europe. “We had nothing.” Another senior executive called Metropolis, Palantir’s main product, a “disaster.”

It had been this sense of desperation that led Chmieliauskas to begin cultivating Cambridge Analytica, a British political consulting firm, backed by Bannon and hedge fund manager Robert Mercer, that aimed to create psychographic profiles of voters using social media data. In 2014, Chmieliauskas, who saw the company as a potential client, suggested that it create an app to scrape Facebook data. Cambridge Analytica never became a Palantir customer, but it took Chmieliauskas’s suggestion and ran with it, eventually accessing the Facebook data of 87 million people without their knowledge.

Palantir would claim that Chmieliauskas had been a rogue employee acting on his own when he suggested the idea. Chmieliauskas says that’s misleading; he says his bosses knew what he was up to and in fact encouraged him to pursue business that was ethically dubious. “They threw me under the bus,” he says. “I’d worked on much shadier deals before Cambridge Analytica.” A Palantir spokeswoman declined to comment. Cambridge Analytica, which denied wrongdoing, went out of business in 2018.

In any case, the new administration presented an opportunity for Palantir—and for Thiel, who had much of his net worth tied up in the company. Just before Election Day in 2016, a federal judge had ruled in a lawsuit brought by Palantir that the Army would have to rebid its database contract and consider Thiel’s company. The court order didn’t mean the Army would buy Palantir’s software, only that it would give it a “hard look,” as Hamish Hume, the company’s lawyer on the case, put it.

Now Karp (and Thiel) had a chance to make a personal appeal to the commander in chief. During the meeting at Trump Tower, Karp promised Trump that Palantir could “help bolster national security and reduce waste.” Karp would later say he had no idea why he’d been invited; all he knew was that his friend had organized it. Of course, Thiel didn’t invite any other defense contractors, such as Raytheon Technologies, Palantir’s main competitor in the bidding on the Army deal, to the meeting.

“Peter’s idea of disrupting government is out there,” Bannon says. “People thought Trump was a disrupter. They had no earthly idea”

Thiel would seem to push the government toward Palantir in other ways. He urged Trump to fire Francis Collins, the longtime director of the National Institutes of Health and an accomplished geneticist who’d headed up the Human Genome Project under Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. This had implications for Palantir, which would have considered the NIH, a massive user of data, a ripe target for its salespeople. Thiel argued that the NIH needed shaking up and suggested that Collins be replaced with Andy Harris, a Republican congressman from Maryland’s rural Eastern Shore and a member of the far-right House Freedom Caucus.

Bannon resisted the effort but agreed to have Collins come to New York in early January to interview for his current job. The agenda included a lunch with Thiel and Masters. In a follow-up email afterward, according to documents that were later made public through a Freedom of Information Act request by independent journalist Andrew Granato, Collins mentioned an eagerness to learn more about Palantir. He said he was meeting with Palantir’s top business development executive. It appears, in retrospect, to have been the beginning of a very successful sales pitch. Collins would be reappointed, and, the following year, the NIH would give Palantir a $7 million contract to help the agency keep track of the research data it was collecting. There would be many more contracts.

Thiel may not have been entirely successful in his push to install loyalists inside the Trump White House, but he didn’t entirely fail either. Michael Kratsios, his former chief of staff, joined the administration as the U.S. chief technology officer and would later become an acting undersecretary of defense, in charge of the Pentagon’s research and development budget. Kevin Harrington, a longtime Thiel adviser, accepted a senior position on the National Security Council. Several others with connections to Thiel would also take senior defense jobs, including Michael Anton, a friend and conservative firebrand—he’d written an essay, “The Flight 93 Election,” that made an intellectual case for Trump—and Justin Mikolay, a former Palantir marketer, who joined the Department of Defense as a speechwriter for Secretary of Defense James Mattis. Mattis’s deputy chief of staff, Anthony DeMartino, and senior adviser, Sally Donnelly, had also done work for Palantir as consultants.

It’s possible, of course, that the appointment of military officials sympathetic to Palantir’s brand of disruption had nothing to do with Thiel—these ideas were gaining currency in government circles even during the Obama administration, and in interviews, Palantir executives emphatically said they had not benefited from preferential treatment. “It’s completely and utterly ludicrous,” Karp said, when I asked him about Palantir’s Trump-era success during a 2019 interview. “It takes 10 years to build this kind of business.”

Ultimately the Army held a bake-off between Palantir and Raytheon for the disputed contract, in which each company was asked to build a prototype system and present it to a panel of soldiers. It was exactly the kind of contest Palantir had called for in a lawsuit a few years prior. Some Palantir insiders wondered if the Pentagon’s leadership had been convinced on the merits—Palantir’s software had indeed improved a lot over the previous few years—or if political pressure had been brought to bear by Thiel and his allies. Either way, in early 2019, the Army announced that Palantir had won outright: The company would get its largest contract ever, worth $800 million or more. The win created momentum, with the company suddenly in the hunt for more Pentagon business.

In 2019, Palantir took over $40 million a year in contracts for Project Maven, a Defense Department effort to use artificial intelligence software to analyze drone footage. That happened despite Palantir’s limited experience in the kind of image-recognition software that Maven used to identify targets—and despite concerns from a government official expressed in an anonymous memo sent to military brass, and first reported by the New York Times, that the company had received preferential treatment in landing the contract. There would be another huge Army contract, announced in December, worth as much as $440 million over four years, plus $10 million from Trump’s brand-new military branch, the Space Force, and $80 million from the Navy. And Palantir ignored the objections of its own employees and immigration activists, renewing its contract with Trump’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency for another $50 million or so.

As the ICE contract showed, Thiel wasn’t above directly linking his business interests with Trump’s most extreme policies. In 2017, Charles Johnson, a longtime Thiel confidant who’d maintained close ties to members of the alt-right, pitched Thiel to invest in a new venture called Clearview AI. The idea, as Johnson explained, was simple: He and an engineer had written software to scrape as many photos as possible from Facebook and other social networks. The software stored the massive trove, along with user names. They would offer this database to police departments and other law enforcement groups, along with a facial recognition algorithm. These tools would allow police to take a picture of an unidentified suspect, upload it into the software, and get a name back.

At the time, Johnson boasted that this technology would be ideal for Trump’s immigration crackdown. “Building algorithms to ID all the illegal immigrants for the deportation squads” was how he put it in a Facebook post. “It was a joke,” says Johnson, who has since cut ties with the alt-right and become a Joe Biden supporter. “But it became real.” Indeed, Clearview would eventually sign a contract to give ICE access to its technology. It would also get Thiel’s help. After hearing Johnson’s pitch, he provided $200,000 in seed capital to the effort. Clearview would land contracts with ICE, the FBI, and numerous federal agencies. Another Thiel-backed contractor, Anduril Industries, capitalized on Trump’s “build the wall” fervor to win a series of contracts with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to contribute digital surveillance technologies, which the company described as a “virtual wall.” Anduril, named after Aragorn’s sword in The Lord of the Rings, is now valued at more than $4 billion.

By the fall of 2020, published estimates were putting Thiel’s personal net worth at around $5 billion, roughly double what it had been before Trump was elected. This was a reflection of his stake in Palantir, which had gone public in August at a valuation of around $20 billion. Thiel then owned about 20% of the company and also held stakes in a number of others whose fortunes had soared. Besides Anduril, there was SpaceX, which was now worth as much as $100 billion thanks in part to a booming business with the federal government, and Airbnb, which had recently gone public. By any financial measure, it had been a good four years.

But those who know Thiel say that even these estimates were probably way too conservative and that his true net worth was closer to $10 billion, possibly much more. That was partly because he had quietly accumulated stakes in a handful of private companies with exceedingly high valuations, including the online payments startup Stripe; a person close to Thiel figures his share is worth at least $1.5 billion. But it was also because Thiel was shielding a large percentage of his investment assets from taxes of any kind.

The strategy was legal, even if it was, from the standpoint of any normal sense of fairness, outrageous. Thiel had parked much of his wealth inside an investment vehicle known as a Roth IRA. Roths are tax-free retirement accounts that were designed for middle-class and lower-middle-class workers, not billionaires—contributions are capped at just $6,000 per year. (You can also convert a traditional IRA into a Roth if you pay taxes on the old account.) It’s illegal to use a Roth account to buy stock in a company you control. And yet, starting in 1999, Thiel used a Roth to buy stock in companies with which he was closely associated—including PayPal and Palantir—for prices that were as low as a thousandth of a penny per share. All the capital gains since then have been tax-free.

The maneuver hinged on an extremely narrow interpretation of what it means to control a company. Thiel didn’t own more than 50% of PayPal at the time of the Roth investment and thus, legally speaking, didn’t control PayPal. But in practice, Thiel had the final say on everything the company did during much of its early history. At one point, in 2001, he threatened to resign as CEO unless the nominally independent board of directors issued him millions of shares. The board agreed because, according to three people familiar with the negotiations, it had no choice; Thiel’s resignation would have killed the company. “It was pay me or I’m going to shoot myself,” recalls one of the people. The board issued almost 4.5 million shares for Thiel to purchase, lending him the money for the transaction. Roughly a third of those shares were bought by Thiel’s Roth IRA. Within a year the new block of shares would be worth $21 million. Thiel would also use the Roth to buy shares in Palantir, whose board was packed with close friends and allies. By the end of 2019, Thiel’s Roth alone was worth $5 billion according to ProPublica, which received leaked copies of Thiel’s tax returns. Four people familiar with Thiel’s finances confirmed the report. Given the performance of the market since then, it’s likely the portfolio is much larger today.

The size of the nest egg, and the aggressive tax strategy Thiel had employed to protect it, put him in a precarious position. According to IRS rules, if a Roth IRA account holder engages in a prohibited transaction—like using the money to invest in a company you legally control—then that person loses the tax break for the entirety of the portfolio’s value. In Thiel’s case that would mean he could be on the hook for a tax bill in the billions. Moreover, in 2014, the Government Accountability Office announced that it had identified 314 taxpayers with IRA balances of more than $25 million, specifically mentioning “founders of companies who use IRAs to invest in nonpublicly traded shares of their newly formed companies”—that is, people who’d done exactly what Thiel did at PayPal and Palantir. The report noted that the IRS planned to investigate these holdings and recommended that Congress pass laws to crack down on the practice. Separately, U.S. tax authorities began an audit of Thiel’s retirement savings.

Thiel was never sanctioned—the audit never turned up anything illegal, according to a person who discussed it with Thiel—but it seemed to make him paranoid. All it would take would be a change in the way the IRS interpreted the rules to force him to pay taxes on the entire Roth account. Or a disgruntled former partner or employee might draw attention to the extent to which Thiel exercised influence over his companies in a way that made it sound like control. “If he violates a single rule, puts a toe in the wrong direction, the government can tax the whole thing,” says another person familiar with the arrangement.

This was scary to Thiel, according to several longtime employees. They say his vulnerability to a change in tax policy or a shift in IRS enforcement seemed to dominate how he related to people around him. Anxiety about a potential crackdown seemed to be part of his motivation to acquire New Zealand citizenship in 2011 and to support Trump in 2016, according to these sources. Now, in 2020, Trump’s reelection prospects were dimming. That left Thiel walking a fine line, staying far enough away from Trump so as not to be blamed if he lost but still close enough to influence Trump’s followers. He never endorsed Trump in 2020, but he was also careful not to criticize the candidate publicly.

Privately he’d taken to referring to Trump’s White House as “the S.S. Minnow”—the hapless fishing charter that runs aground in the show Gilligan’s Island. Of course, in this analogy, Trump was the skipper. There were, as Thiel told a friend in a text, “lots of Gilligans.” In an unrelated nautical metaphor, Thiel said that changes to Trump’s campaign were the equivalent of “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.” Similar comments leaked to the press, which reported that he was souring on Trump because of the administration’s failure to adequately respond to the coronavirus pandemic. But this wasn’t true. Thiel supported Trump on Covid-19, telling friends he thought the lockdowns in states led by Democratic governors were “crazy” and overly broad.

Nor was Thiel or his inner circle moderating. After Trump’s Supreme Court pick, Neil Gorsuch, sided with liberals and moderates in ruling that gay and transgender workers were deserving of civil rights protections, Masters, the Thiel adviser who’d served on the transition, complained that the party had betrayed conservatives. He wrote on Twitter, sardonically, that the point of the Republican Party seemed to be, among other things, “to protect private equity, low taxes, free pornography.”

After Trump’s loss in November, Thiel’s employees and allies were abuzz with rumors about secret uncounted votes in key swing states and how the election’s outcome was somehow in doubt. Eric Weinstein, a podcast host and longtime Thiel adviser, tweeted videos of a purported Postal Service whistleblower. (The claims, which turned out to have been fabricated, were distributed by conservative journalist and provocateur James O’Keefe, another Thiel ally who has received funds from him in the past.) Masters, meanwhile, tweeted darkly about Dominion Voting Systems, amplifying a conspiracy theory alleging that the manufacturer of electronic voting machines had somehow tampered with the results. He also claimed, offering no evidence, that dead people had voted in Milwaukee and Detroit.

In March a newly created political action committee announced that Thiel had pledged a $10 million donation to support the potential Senate candidacy of J.D. Vance, author of the memoir Hillbilly Elegy. Vance worked for Mithril Capital Management, another of Thiel’s venture capital firms, this one named after the magically light metal in The Lord of the Rings. Not long after Hillbilly Elegy came out, Vance moved to Ohio and began plotting a political career. He also started a new Thiel-backed fund focused on investing in Midwestern startups called Narya Capital Management—“Narya” being Elvish for “ring of fire” in The Lord of the Rings.

Vance had once been a critic of Trump. “Fellow Christians, everyone is watching us when we apologize for this man,” he’d tweeted after the infamous Access Hollywood tape leaked. “Lord help us.” But a week before the announcement that Thiel was backing his Senate candidacy, Vance appeared on America First, the podcast run by former Trump adviser Sebastian Gorka, and proclaimed himself a convert to Trump’s Make America Great Again movement. He said that he’d come to agree with Trump’s assessment of what he called “the American Elite.” Vance proclaimed, “They don’t care about the country that has made them who they are.” Then he met with Thiel and Trump at Mar-a-Lago. He deleted his old #nevertrump posts.

In July, Vance, a graduate of Yale Law School, made his run official, railing against universities, anti-American business leaders, “woke” hedge funds, and “Fauci’s cabal” (a reference to Covid restrictions). He proposed cracking down on immigration, curbing China’s rise, and breaking up big tech companies for censoring conservative speech—all positions Thiel had been pushing. Days later, Vance appeared on Fox News and launched an attack on Google, a competitor to Palantir for government contracts. “Google, right now, is actively conspiring with and working with the Chinese government,” Vance said. This charge was spurious and almost identical to one Thiel had made two years earlier at the National Conservatism Conference, where Vance also spoke. At that event, Thiel accused Google, without evidence, of being “treasonous” for failing to work more closely with the Defense Department and for doing business in China.

Masters, meanwhile, announced his own run for Senate in Arizona, proving himself a capable advocate for Thiel, who made another $10 million commitment to his candidacy. Like Vance’s, the Masters platform reads like an extension of Thiel’s worldview, combining Trump-style immigration politics (“Obviously this works,” he said in a video shot at a section of the border wall), complaints about diversity efforts, and plans to rein in tech companies, especially ones in which Thiel doesn’t have an interest. His Thiel-backed PAC recently aired an advertisement attacking a fellow candidate, Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, for refusing to overturn the state’s 2020 election results.

If they win their primaries, and if Republicans win control of the Senate in 2022, Masters and Vance—along with the other two populist nationalists who have received substantial support from Thiel, Josh Hawley of Missouri and Ted Cruz of Texas—would arguably offer Thiel a level of influence greater than what he enjoyed under Trump. A Republican-controlled Senate, especially one where Thiel’s politics are ascendant, would also be ideal for Thiel’s government contractors and for protecting the tax-advantaged status of his Roth IRA.

But Masters and Vance offer more than Trump because, unlike the former president, they’re highly disciplined ideologues who seem committed to popularizing their patron’s political agenda. They are, in other words, as out there as Thiel is. Even better, Masters and Vance both work for Thiel, and not just in the sense that his PAC is paying for TV advertising on their behalf. Masters remains chief operating officer of Thiel Capital and president of the Thiel Foundation; Thiel is a key investor in Narya, Vance’s investment firm. Vance and Thiel recently invested in Rumble, a YouTube competitor that caters to Trumpist talking heads, such as the talk show host Dan Bongino, New York Representative Elise Stefanik, and the former president himself.

Thiel is said to be in the market for other candidates ahead of the midterms and the 2024 election. “He has not reverted back to Republicanism,” Bannon says. “He’s full MAGA.” It’s not clear that Trump’s old slogan has much political salience anymore, but if Silicon Valley’s most influential venture capitalist succeeds in appropriating Trumpism, that would, at the very least, keep America great for Peter Thiel.

From The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power by Max Chafkin, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright 2021 by Max Chafkin.

No comments:

Post a Comment