'MAYBE' TECH

China prepares to test thorium-fuelled nuclear reactorIf China’s experimental reactor is a success it could lead to commercialization and help the nation meet its climate goals.

Smriti Mallapaty

China has more than 50 conventional nuclear power plants, such as this, but the experimental thorium reactor in Wuwei will be a first.

Credit: Costfoto/Barcroft Media/Getty

Scientists are excited about an experimental nuclear reactor using thorium as fuel, which is about to begin tests in China. Although this radioactive element has been trialled in reactors before, experts say that China is the first to have a shot at commercializing the technology.

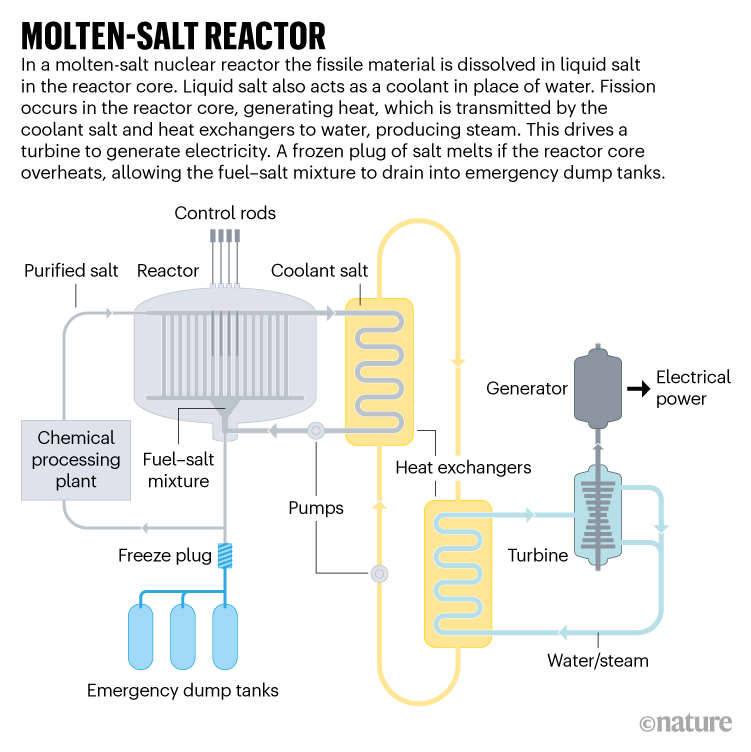

The reactor is unusual in that it has molten salts circulating inside it instead of water. It has the potential to produce nuclear energy that is relatively safe and cheap, while also generating a much smaller amount of very long-lived radioactive waste than conventional reactors.

Construction of the experimental thorium reactor in Wuwei, on the outskirts of the Gobi Desert, was due to be completed by the end of August — with trial runs scheduled for this month, according to the government of Gansu province.

Thorium is a weakly radioactive, silvery metal found naturally in rocks, and currently has little industrial use. It is a waste product of the growing rare-earth mining industry in China, and is therefore an attractive alternative to imported uranium, say researchers.

Scientists are excited about an experimental nuclear reactor using thorium as fuel, which is about to begin tests in China. Although this radioactive element has been trialled in reactors before, experts say that China is the first to have a shot at commercializing the technology.

The reactor is unusual in that it has molten salts circulating inside it instead of water. It has the potential to produce nuclear energy that is relatively safe and cheap, while also generating a much smaller amount of very long-lived radioactive waste than conventional reactors.

Construction of the experimental thorium reactor in Wuwei, on the outskirts of the Gobi Desert, was due to be completed by the end of August — with trial runs scheduled for this month, according to the government of Gansu province.

Thorium is a weakly radioactive, silvery metal found naturally in rocks, and currently has little industrial use. It is a waste product of the growing rare-earth mining industry in China, and is therefore an attractive alternative to imported uranium, say researchers.

Powerful potential

“Thorium is much more plentiful than uranium and so it would be a very useful technology to have in 50 or 100 years’ time,” when uranium reserves start to run low, says Lyndon Edwards, a nuclear engineer at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation in Sydney. But the technology will take many decades to realize, so we need to start now, he adds.

China launched its molten-salt reactor programme in 2011, investing some 3 billion yuan (US$500 million), according to Ritsuo Yoshioka, former president of the International Thorium Molten-Salt Forum in Oiso, Japan, who has worked closely with Chinese researchers.

Operated by the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics (SINAP), the Wuwei reactor is designed to produce just 2 megawatts of thermal energy, which is only enough to power up to 1,000 homes. But if the experiments are a success, China hopes to build a 373-megawatt reactor by 2030, which could power hundreds of thousands of homes.

These reactors are among the “perfect technologies” for helping China to achieve its goal of zero carbon emissions by around 2050, says energy modeller Jiang Kejun at the Energy Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission in Beijing.

The naturally occurring isotope thorium-232 cannot undergo fission, but when irradiated in a reactor, it absorbs neutrons to form uranium-233, which is a fissile material that generates heat.

Thorium has been tested as a fuel in other types of nuclear reactor in countries including the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom, and is part of a nuclear programme in India. But it has so far not proved cost effective because it is more expensive to extract than uranium and, unlike some naturally occurring isotopes of uranium, needs to be converted into a fissile material.

Some researchers support thorium as a fuel because they say its waste products have less chance of being weaponized than do those of uranium, but others have argued that risks still exist.

Source: US Department of Energy/International Atomic Energy Agency

Blast from the past

When China switches on its experimental reactor, it will be the first molten-salt reactor operating since 1969, when US researchers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee shut theirs down. And it will be the first molten-salt reactor to be fuelled by thorium. Researchers who have collaborated with SINAP say the Chinese design copies that of Oak Ridge, but improves on it by calling on decades of innovation in manufacturing, materials and instrumentation.

Researchers in China directly involved with the reactor did not respond to requests for confirmation of the reactor’s design and when exactly tests will begin.

Compared with light-water reactors in conventional nuclear power stations, molten-salt reactors operate at significantly higher temperatures, which means they could generate electricity much more efficiently, says Charles Forsberg, a nuclear engineer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

China’s reactor will use fluoride-based salts, which melt into a colourless, transparent liquid when heated to about 450 ºC. The salt acts as a coolant to transport heat from the reactor core. In addition, rather than solid fuel rods, molten-salt reactors also use the liquid salt as a substrate for the fuel, such as thorium, to be directly dissolved into the core.

Molten-salt reactors are considered to be relatively safe because the fuel is already dissolved in liquid and they operate at lower pressures than do conventional nuclear reactors, which reduces the risk of explosive meltdowns.

Yoshioka says many countries are working on molten-salt reactors — to generate cheaper electricity from uranium or to use waste plutonium from light-water reactors as fuel — but China alone is attempting to use thorium fuel.

Thorium pellets at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in Mumbai, India.

Credit: Pallava Bagla/Corbis/Getty

Next-generation reactors

China’s reactor will be “a test bed to do a lot of learning”, says Forsberg, from analysing corrosion to characterizing the radionucleotide composition of the mixture as it circulates.

“We are going to learn so much new science,” agrees Simon Middleburgh, a nuclear materials scientist at Bangor University, UK. “If they would let me, I’d be on the first plane there.”

It could take months for China’s reactor to reach full operation. “If anything along the way goes wrong, you can’t continue, and have to stop and start again,” says Middleburgh. For example, the pumps might fail, pipes could corrode or a blockage might occur. Nevertheless, scientists are hopeful of success.

Molten-salt reactors are just one of many advanced nuclear technologies China is investing in. In 2002, an intergovernmental forum identified six promising reactor technologies to fast-track by 2030, including reactors cooled by lead or sodium liquids. China has programmes for all of them.

Some of these reactor types could replace coal-fuelled power plants, says David Fishman, a project manager at the Lantau Group energy consultancy in Hong Kong. “As China cruises towards carbon neutrality, it could pull out [power plant] boilers and retrofit them with nuclear reactors.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02459-w

Why China is developing a game-changing thorium-fuelled nuclear reactor

Issued on: 12/09/2021 -

A new page in the history of nuclear energy could be written this September, in the middle of the Gobi Desert, in the north of China. At the end of August, Beijing announced that it had completed the construction of its first thorium-fuelled molten-salt nuclear reactor, with plans to begin the first tests of this alternative technology to current nuclear reactors within the next two weeks.

Built not far from the northern city of Wuwei, the low-powered prototype can as yet only produce energy for around 1,000 homes, according to the scientific journal Nature.

But if the upcoming tests succeed, Chinese authorities will start a programme to build another reactor capable of generating electricity for over 100,000 homes. Beijing could then become an exporter of a reactor technology that has been the subject of much discussion for over 40 years, according to French financial newspaper Les Echos.

Lower accident risks?

The Chinese reactor could be the first molten-salt reactor operating in the world since 1969, when the US abandoned its Oak Ridge National Laboratory facility in Tennessee.

“Almost all current reactors use uranium as fuel and water, instead of molten salt and thorium," which will be used in China’s new plant, Jean-Claude Garnier, head of France’s Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), told FRANCE 24.

These two "new" ingredients were not chosen by accident by Beijing: molten-salt reactors are among the most promising technologies for power plants, according to the Generation IV forum – a US initiative to push for international cooperation on civil nuclear power.

With molten-salt technology, "it is the salt itself that becomes the fuel", Sylvain David, research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and nuclear reactors specialist, explained in a FRANCE 24 interview. The crystals are mixed with nuclear material – either uranium or thorium – heated to over 500°C to become liquid, and are then be able to transport the heat and energy produced.

Theoretically, this process would make the installations safer. "Some accident risks are supposedly eliminated because liquid burning avoids situations where the nuclear reaction can get out of control and damage the reactor structures," Jean-Claude Garnier added.

There's another advantage for China: this type of reactor does not need to be built near watercourses, since the molten salts themselves "serve as a coolant, unlike conventional uranium power plants that need huge amounts of water to cool their reactors", French newspaper Les Echos noted. As a result, the reactors can be installed in isolated and arid regions… like the Gobi Desert.

China's plentiful supply

Beijing has also opted to use thorium rather than uranium in its new molten-salt reactor, a combination that has drawn attention from experts for years. This is mostly because “there is much more thorium than uranium in nature”, Francesco D’Auria, nuclear reactor technology specialist at the University of Pisa, told FRANCE 24.

In addition, thorium belongs to a famous family of rare-earth metals that are much more abundant in China than elsewhere; this is the icing on the cake for Chinese authorities, who could increase its energy independence from major uranium exporting countries, such as Canada and Australia, two countries whose diplomatic relations with China have collapsed in recent years.

Beijing’s investment is also a long-term one. “For now, there is enough uranium to fuel all operating reactors. But if the number of reactors increases, we could reach a situation where supply would no longer keep up, and using thorium can drastically reduce the need for uranium. That makes it a potentially more sustainable option," Sylvain David explained.

A 'greener' nuclear energy?

According to supporters of thorium, it would also a "greener" solution. Unlike the uranium currently used in nuclear power plants, burning thorium does not create plutonium, a highly toxic chemical element, Nature pointed out.

With so many positives on their side, why are molten salts and thorium only being used now? “Essentially because uranium 235 was the natural candidate for nuclear reactors and the market did not look much further," Francesco D'Auria added.

Radiation, corrosion and... nuclear weapons

Among the three main candidates for nuclear reaction – uranium 235, uranium 238 and thorium – the first is “the only isotope naturally fissile”, Sylvain David explained. The other two must be bombarded with neutrons for the material to become fissile (able to undergo nuclear fission) and be used by a reactor: a possible but more complex process.

Once that is done on thorium, it produces uranium 233, the fissile material needed for nuclear power generation. That then becomes another problem with thorium: "The radiation emitted by uranium 233 is stronger than that of the other isotopes, so you have to be more careful," Francesco D'Auria warned.

The feasibility of molten-salt reactors is also questionable as it creates further technical problems. "At very high temperatures, the salt can corrode the reactor’s structures, which need to be protected in some manner," Jean-Claude Garnier explained.

The stakes are clearly high for the Chinese tests and they will be watched very closely around the world in order to see how Beijing hopes to overcome these obstacles. But even if China ends up claiming victory, they should not rejoice too quickly, Francesco D’Auria said: "The problem with corrosive products is that you don't realise their damage until five to 10 years after."

Moreover, the expert claims there is no reason to celebrate a nuclear reactor that not only produces energy, but also uranium 233. "This is an isotope that does not exist in nature and that can be used to build an atomic bomb," pointed out Francesco D'Auria.

As such, China could end up revolutionising the nuclear industry but, at the same time, they might once more alarm supporters of non-proliferation around the world.

Issued on: 12/09/2021 -

China has around 50 traditional nuclear plants running, such as in

Taishan, pictured here on June 17, 2021. AP

Text by: Sébastian SEIBT

China is poised to test a thorium-powered nuclear reactor in September, the world’s first since 1969. The theory is that this new molten-salt technology will be “safer” and “greener” than regular uranium reactors, and so could help Beijing meet its climate goals. Yet is the country's investment in this also geostrategic?

Text by: Sébastian SEIBT

China is poised to test a thorium-powered nuclear reactor in September, the world’s first since 1969. The theory is that this new molten-salt technology will be “safer” and “greener” than regular uranium reactors, and so could help Beijing meet its climate goals. Yet is the country's investment in this also geostrategic?

A new page in the history of nuclear energy could be written this September, in the middle of the Gobi Desert, in the north of China. At the end of August, Beijing announced that it had completed the construction of its first thorium-fuelled molten-salt nuclear reactor, with plans to begin the first tests of this alternative technology to current nuclear reactors within the next two weeks.

Built not far from the northern city of Wuwei, the low-powered prototype can as yet only produce energy for around 1,000 homes, according to the scientific journal Nature.

But if the upcoming tests succeed, Chinese authorities will start a programme to build another reactor capable of generating electricity for over 100,000 homes. Beijing could then become an exporter of a reactor technology that has been the subject of much discussion for over 40 years, according to French financial newspaper Les Echos.

Lower accident risks?

The Chinese reactor could be the first molten-salt reactor operating in the world since 1969, when the US abandoned its Oak Ridge National Laboratory facility in Tennessee.

“Almost all current reactors use uranium as fuel and water, instead of molten salt and thorium," which will be used in China’s new plant, Jean-Claude Garnier, head of France’s Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), told FRANCE 24.

These two "new" ingredients were not chosen by accident by Beijing: molten-salt reactors are among the most promising technologies for power plants, according to the Generation IV forum – a US initiative to push for international cooperation on civil nuclear power.

With molten-salt technology, "it is the salt itself that becomes the fuel", Sylvain David, research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and nuclear reactors specialist, explained in a FRANCE 24 interview. The crystals are mixed with nuclear material – either uranium or thorium – heated to over 500°C to become liquid, and are then be able to transport the heat and energy produced.

Theoretically, this process would make the installations safer. "Some accident risks are supposedly eliminated because liquid burning avoids situations where the nuclear reaction can get out of control and damage the reactor structures," Jean-Claude Garnier added.

There's another advantage for China: this type of reactor does not need to be built near watercourses, since the molten salts themselves "serve as a coolant, unlike conventional uranium power plants that need huge amounts of water to cool their reactors", French newspaper Les Echos noted. As a result, the reactors can be installed in isolated and arid regions… like the Gobi Desert.

China's plentiful supply

Beijing has also opted to use thorium rather than uranium in its new molten-salt reactor, a combination that has drawn attention from experts for years. This is mostly because “there is much more thorium than uranium in nature”, Francesco D’Auria, nuclear reactor technology specialist at the University of Pisa, told FRANCE 24.

In addition, thorium belongs to a famous family of rare-earth metals that are much more abundant in China than elsewhere; this is the icing on the cake for Chinese authorities, who could increase its energy independence from major uranium exporting countries, such as Canada and Australia, two countries whose diplomatic relations with China have collapsed in recent years.

Beijing’s investment is also a long-term one. “For now, there is enough uranium to fuel all operating reactors. But if the number of reactors increases, we could reach a situation where supply would no longer keep up, and using thorium can drastically reduce the need for uranium. That makes it a potentially more sustainable option," Sylvain David explained.

A 'greener' nuclear energy?

According to supporters of thorium, it would also a "greener" solution. Unlike the uranium currently used in nuclear power plants, burning thorium does not create plutonium, a highly toxic chemical element, Nature pointed out.

With so many positives on their side, why are molten salts and thorium only being used now? “Essentially because uranium 235 was the natural candidate for nuclear reactors and the market did not look much further," Francesco D'Auria added.

Radiation, corrosion and... nuclear weapons

Among the three main candidates for nuclear reaction – uranium 235, uranium 238 and thorium – the first is “the only isotope naturally fissile”, Sylvain David explained. The other two must be bombarded with neutrons for the material to become fissile (able to undergo nuclear fission) and be used by a reactor: a possible but more complex process.

Once that is done on thorium, it produces uranium 233, the fissile material needed for nuclear power generation. That then becomes another problem with thorium: "The radiation emitted by uranium 233 is stronger than that of the other isotopes, so you have to be more careful," Francesco D'Auria warned.

The feasibility of molten-salt reactors is also questionable as it creates further technical problems. "At very high temperatures, the salt can corrode the reactor’s structures, which need to be protected in some manner," Jean-Claude Garnier explained.

The stakes are clearly high for the Chinese tests and they will be watched very closely around the world in order to see how Beijing hopes to overcome these obstacles. But even if China ends up claiming victory, they should not rejoice too quickly, Francesco D’Auria said: "The problem with corrosive products is that you don't realise their damage until five to 10 years after."

Moreover, the expert claims there is no reason to celebrate a nuclear reactor that not only produces energy, but also uranium 233. "This is an isotope that does not exist in nature and that can be used to build an atomic bomb," pointed out Francesco D'Auria.

As such, China could end up revolutionising the nuclear industry but, at the same time, they might once more alarm supporters of non-proliferation around the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment