Fight scenes weren’t authentic, the acting was stiff and the cameras never moved, but monsters and magic effects in 1950s wuxia films thrilled cinema-goers

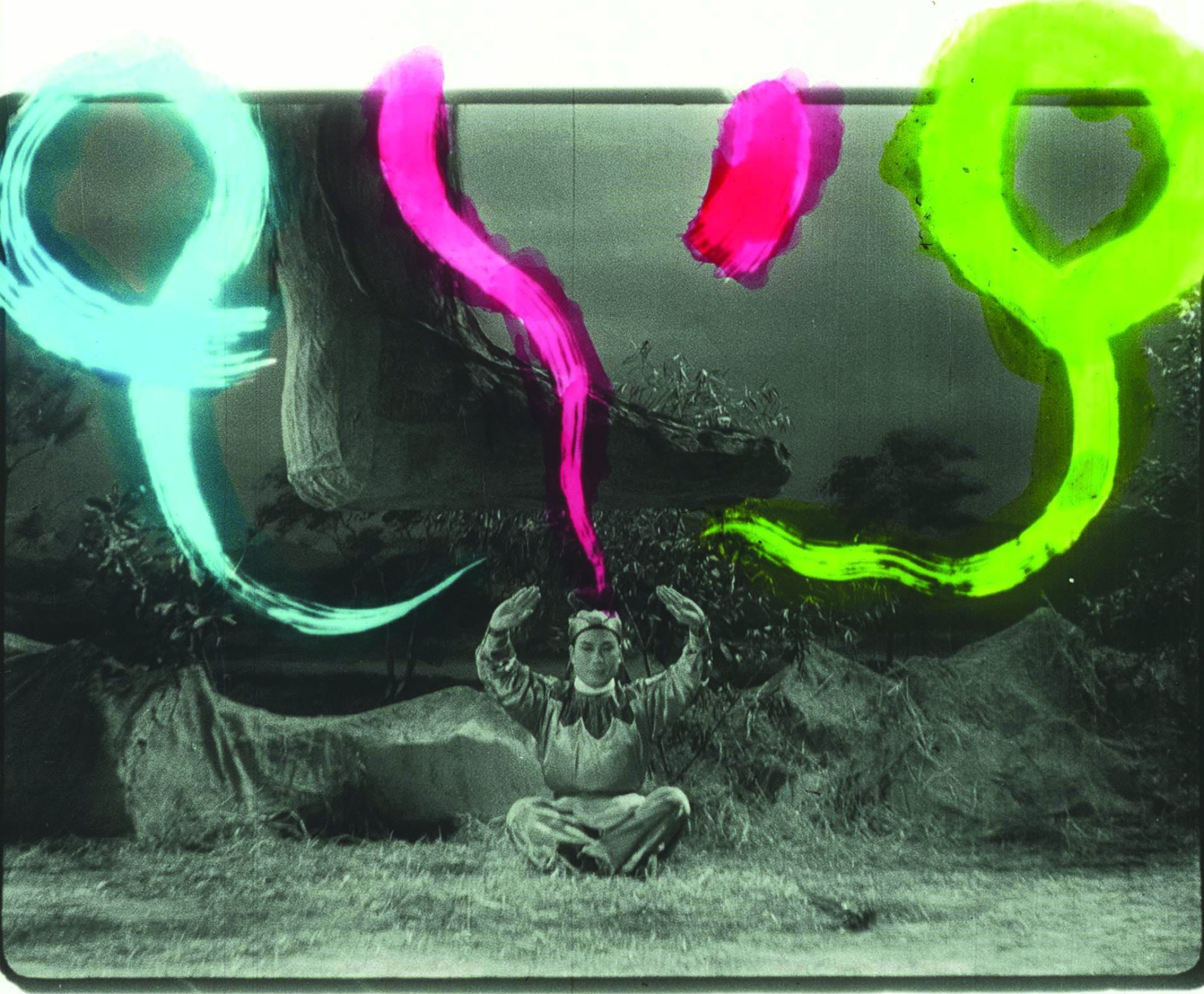

Magic effects such as palm rays were usually drawn directly onto the celluloid, while the appearance of levitation was shown by means of reversed film

Richard James Havis

SCMP

Published: 5 Sep, 2021

A still from 1963 film The Golden Scissors, Part One features a flying sword (left).

Martial arts special effects were primitive, but so was the acting and camerawork.

Wuxia films didn’t begin with Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers studio, and there were kung fu films long before Bruce Lee.

In fact, Hong Kong’s first martial arts film, made in 1938, told the story of legendary Cantonese hero Fong Sai-yuk long before Jet Li Lianjie committed Fong’s adventures to film. Even Li’s indelible characterisation of the masterful Wong Fei-hung was predated by the long-running Wong Fei-hung film series starring Kwan Tak-hing.

Wuxia films didn’t begin with Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers studio, and there were kung fu films long before Bruce Lee.

In fact, Hong Kong’s first martial arts film, made in 1938, told the story of legendary Cantonese hero Fong Sai-yuk long before Jet Li Lianjie committed Fong’s adventures to film. Even Li’s indelible characterisation of the masterful Wong Fei-hung was predated by the long-running Wong Fei-hung film series starring Kwan Tak-hing.

Special effects, too, didn’t arrive with Tsui Hark’s Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain and Tsui and Ching Siu-tung’s A Chinese Ghost Story – effects utilising props, make-up and costumes had been around since the dawn of the genre.

Even Hong Kong’s wirework techniques, used to give the impression of long leaps or flying and beloved of martial arts choreographers such as Yuen Woo-ping, were invented long ago, in the moviemaking powerhouse of Shanghai in the 1920s.

Even Hong Kong’s wirework techniques, used to give the impression of long leaps or flying and beloved of martial arts choreographers such as Yuen Woo-ping, were invented long ago, in the moviemaking powerhouse of Shanghai in the 1920s.

A still from Ingenious Swords, Part One (1962).

We recall some almost forgotten Hong Kong martial arts films and their use of special effects.

How it all began

The first martial arts films were made in Shanghai in the 1920s, but the genre didn’t start in Hong Kong until 1938, with the four-part film serial The Adventures of Fong Sai Yuk.

According to Yu Mo-wan’s Swords, Chivalry and Palm Power, Hong Kong did not have the talent to sustain a martial arts film industry until 1937, when directors working in the genre relocated from Shanghai to Hong Kong because of the Japanese invasion of China. Martial arts films took off in Hong Kong in the 1940s.

The heroes of Shanghainese films were often rebellious, but the Cantonese versions of these characters were chivalrous and upheld Confucian values. Noting a scene in which a martial artist climbs some stairs on his hands while holding cigarettes with his feet, Yu writes that the value of the films lies in their “documentation of actual acrobatic stunts and martial arts routines”.

‘I’m versatile’: how Michelle Yeoh became a martial arts movie star

29 Aug 2021

The genre flourished in the 1950s with some notable adaptations of martial arts novels, and many inferior films based on pulp fiction and old Shanghainese films

A major star of this period – she made around 150 wuxia films – was actress Yu So-chow, daughter of master Yu Jim-yuen, the founder of the Beijing opera school attended by Jackie Chan.

Cantonese-language martial arts films enjoyed a golden age in the early 1960s, with hits like The Story of Book and Sword and The Yin Yang Blade. Hong Kong acting legend Josephine Siao Fong-fong was a prominent star of wuxia movies in this period.

Yu So-chow in a scene from The Secret Book (1961).

Around 1967, Cantonese martial arts movies were replaced by the modern-looking colour films of Shaw Brothers’ “Colour Wuxia Century”, shot in Mandarin Chinese, although Cantonese productions limped on for a few more years.

Men in monster suits

Magic and monsters were popular elements of the Cantonese fantastique wuxia films. Buddha’s Palm, the first of a four-part Cantonese-language film series directed by Ling Wan in 1964, has to be seen to be believed.

A still from The Furious Buddha’s Palm (1965).

A straightforward plot about a young martial artist seeking the secret of the Eight-Palm Buddha technique is enlivened by a kung fu chicken (although it’s meant to be an eagle), a kung fu bat and a kung fu yeti/unicorn. The beasts are all man-sized, and are mainly played by former circus performer Chan Siu-ping, an acknowledged expert in acting in animal suits.

“At that time, in Buddha’s Palm and in all the other Cantonese pictures that called for it, I was the actor who played those strange beasts, principally for the money,” Chan told the Hong Kong Film Archive.

“A martial arts coach would get only HK$25 a day, but playing these strange beasts, you were paid HK$40 to HK$50 a day. About 99 per cent of these roles in Hong Kong cinema were played by me.”

Josephine Siao and the eagle, played by Chan Siu-ping, in a still from Marching Down South (1963). Photo: YouTube

“I was the eagle in Buddha’s Palm and Marching Down South, and I was the ape in a contemporary Fung Bobo picture. Another time I was the ‘hairy monster.’ I had a sharp eye to observe these animals. The toughest thing to play were the snakes and crocodiles – creatures that crawl across the floor,” said Chan.

A world of special effects

Flying swords, palm rays, magic darts, levitation by means of reversed film, and wirework played a big part in the fantastique films of Shanghai, and Hong Kong directors continued the tradition.

Effects like palm rays were usually drawn directly onto the celluloid, and specialised artists were employed for the task. Sacred Fire Decree of the Kung Fu World, a box-office hit directed by Siu Sang in 1965, used such techniques to become a box-office hit.

A still from The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple, Part Three (1957).

“At that time, the technology we had for making martial arts pictures was not advanced. It was tough to do things like show the ‘whoosh’ of palm power emanating from your hand,” Siu told the Film Archive.

“Once you had your hand ready to project the whoosh, the actor had to stand very still – he couldn’t move. Then you literally had to draw in that whoosh, which gradually became larger as a beam projected through the sky. If it was a colour production, the beam would be coloured, and the red would be shown fighting the green. This usually impressed children.”

What were the films like?

Acting was stagey and the camera rarely moved – according to an interview with a cinematographer, this was not because of technical limitations, but because the directors never thought to move them.

A still from The Legend of the Owl (1981), a Hong Kong martial arts comedy which blends influences from wuxia novels and foreign pop culture such as the Star Wars movies. Photo: Fortune Star Media Limited

“The action sequences were choreographed on the stage model of formulaic and fake fighting, and lacked the kind of stage aesthetics that made it acceptable on stage,” wrote film historian Law Kar of the movies of the 1950s.

By the early 1960s things had improved. “More effort was being put into the action sequences to add to their appeal,” Law wrote. “New weapons were being pulled out of the bag of tricks, and an emphasis was put on choreography and design.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre.

Read

our comprehensive explainer here.

Want more articles like this? Follow

SCMP Film on Facebook

our comprehensive explainer here.

Want more articles like this? Follow

SCMP Film on Facebook

No comments:

Post a Comment