The asteroids are 4.6-billion-year-old relics from the solar system's earliest days.

Lucy lifts off from Cape Canaveral.

Jackson Ryan

Oct. 16, 2021

A United Launch Alliance Atlas V 401 rocket flared to life under the cover of dark at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida just after 2:30 a.m. local time Saturday morning. Encased within the pencil-shaped payload fairing atop the rocket was NASA's latest interplanetary explorer: a spacecraft named Lucy.

It was the 100th launch from Cape Canaveral Space Launch Complex 41. Approximately 58 minutes after launch the probe, which is about as wide as a bus, was released from the second stage rocket booster to begin its long journey toward Jupiter's orbit. The United Launch Alliance team celebrated with hugs and clapping in its mission control room.

"It was one of the most exciting experiences of my life," Hal Levison, principal investigator of the Lucy mission, said post-launch. "It was truly awesome, in the old-fashioned meaning of the word."

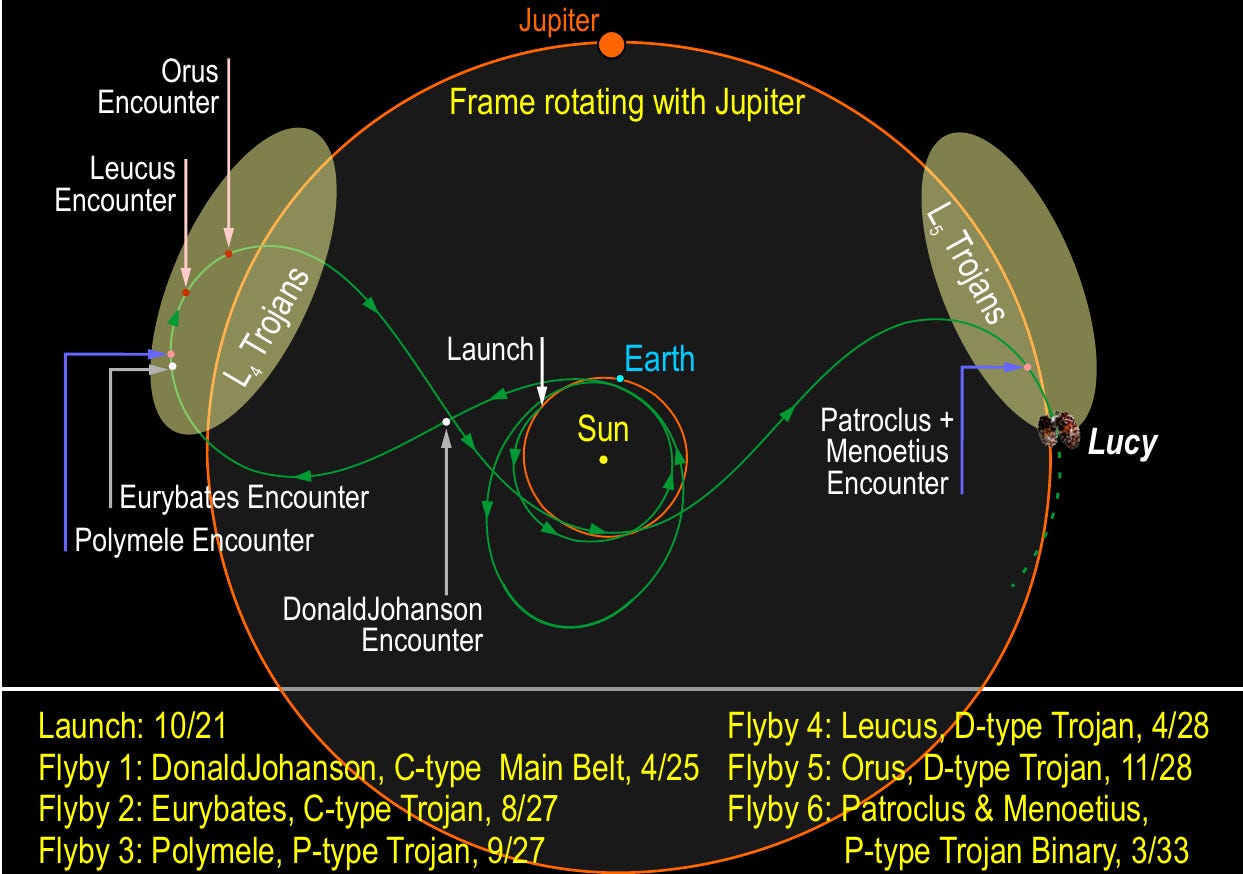

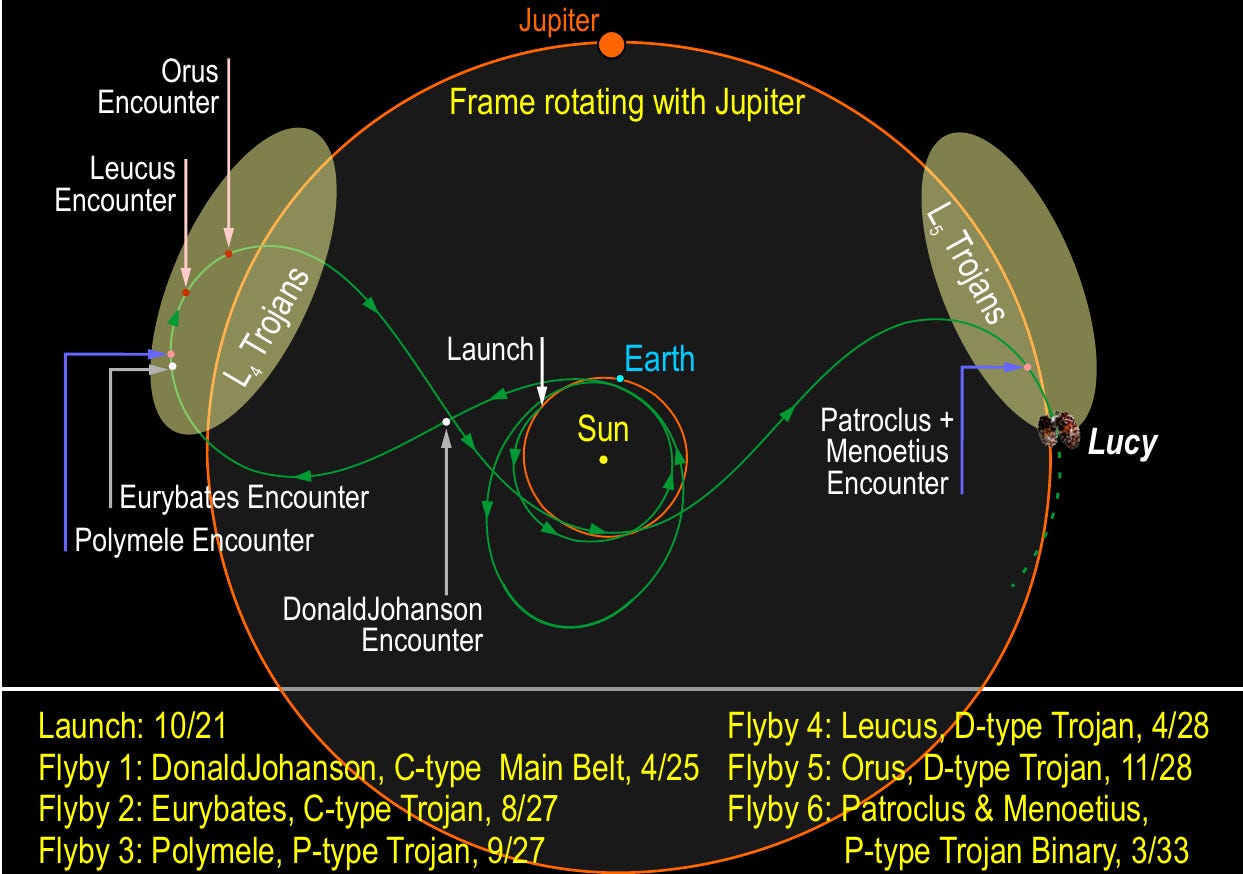

Over the next two years, Lucy will use Earth's gravity twice to swing toward the solar system's largest planet. But the gas giant isn't Lucy's destination. Instead, it'll explore a series of asteroids, locked in Jupiter's orbit, known as the Trojans.

These asteroids have never been studied up close before and move as huge swarms, or camps, at the "Lagrangian points" in Jupiter's orbit. The Lagrangian points are regions where gravity's push and pull lock the camps in place, leading and trailing Jupiter in its journey around the sun in perpetuity.

The collection of amorphous space rocks is like a series of cosmic fossils, providing a window into the earliest era of our solar system, some 4.6 billion years ago. Lucy will act as a cosmic palaeontologist, flying past these eight different "fossils" at a distance and studying their surfaces with infrared imagers and cameras.

"No spacecraft has visited so many objects before, and each is a potential window into the material and conditions of the early solar system," says Alan Duffy, an astrophysicist at Swinburne University in Melbourne.

The idea of examining fossils is core to the mission's philosophy -- right down to its name. "Lucy" is derived from a hominid skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. The skeleton was dubbed Lucy because the Beatles' song Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds was playing in the scientists' camp after the find. Words from all four Beatles are contained on a plaque inside the spacecraft.

Though the early morning launch and separation was marked down as a success on Lucy's extensive to-do list, the spacecraft had to overcome one final, giant hurdle before it was ready to sail out of Earth's backyard. About one hour into its flight, the probe experienced "20 minutes of terror," as it unfurled its 24 foot wide decagonal solar panels.

The panels are critical to the spacecraft's success and will power Lucy during the 12-year journey toward the Trojans. They can supply about 500 watts of power -- about the same amount of energy necessary to run a washing machine, according to NASA. And Lucy will need every watt, because it'll be the farthest solar-powered spacecraft should it reach its destinations.

Lucy's complex trajectory and flyby dates

NASA's Lucy mission: 20 minutes of terror will define the next 12 years

One of Lucy's engineers takes us behind the scenes of the momentous mission to the Trojan asteroids that share Jupiter's orbit around the sun.

Monisha Ravisetti

Oct. 16, 2021

Lucy will journey to eight asteroids over the next dozen years.

Here's the launch sequence from the eyes of NASA.

"When the rocket lifts off from the ground, that's very visual and exciting," said Emily Gramlich, a system integration and test engineer at Lockheed Martin and a Lucy mission specialist. "As the rocket ascends, we go through the atmosphere."

During that phase, Lucy will reach its maximum speed and pressure. "Then," Gramlich continued, "we have separation from the boosters and then the bearing will deploy and open us up to outer space."

Lucy's bootcamp

You name it, Lucy's been through it. Several times.

"We do an acoustic test and a vibration test in a large building on the Waterton campus," said Gramlich referring to Lockheed Martin's testing grounds in Colorado. "We shake the spacecraft really hard and then we blast it with sound to simulate mostly the launch."

The most physically intense part of Lucy's 12-year journey, she said, will be the launch happening this weekend. Once it's in space, the situation will become much calmer. But space has its own extremes, so the team has tried to ensure that Lucy will be shielded from those, too.

"We take the spacecraft and put it into a giant thermal chamber and run it through all the temperature ranges that it is going to see in space -- hot and cold, light and no light," Gramlich said.

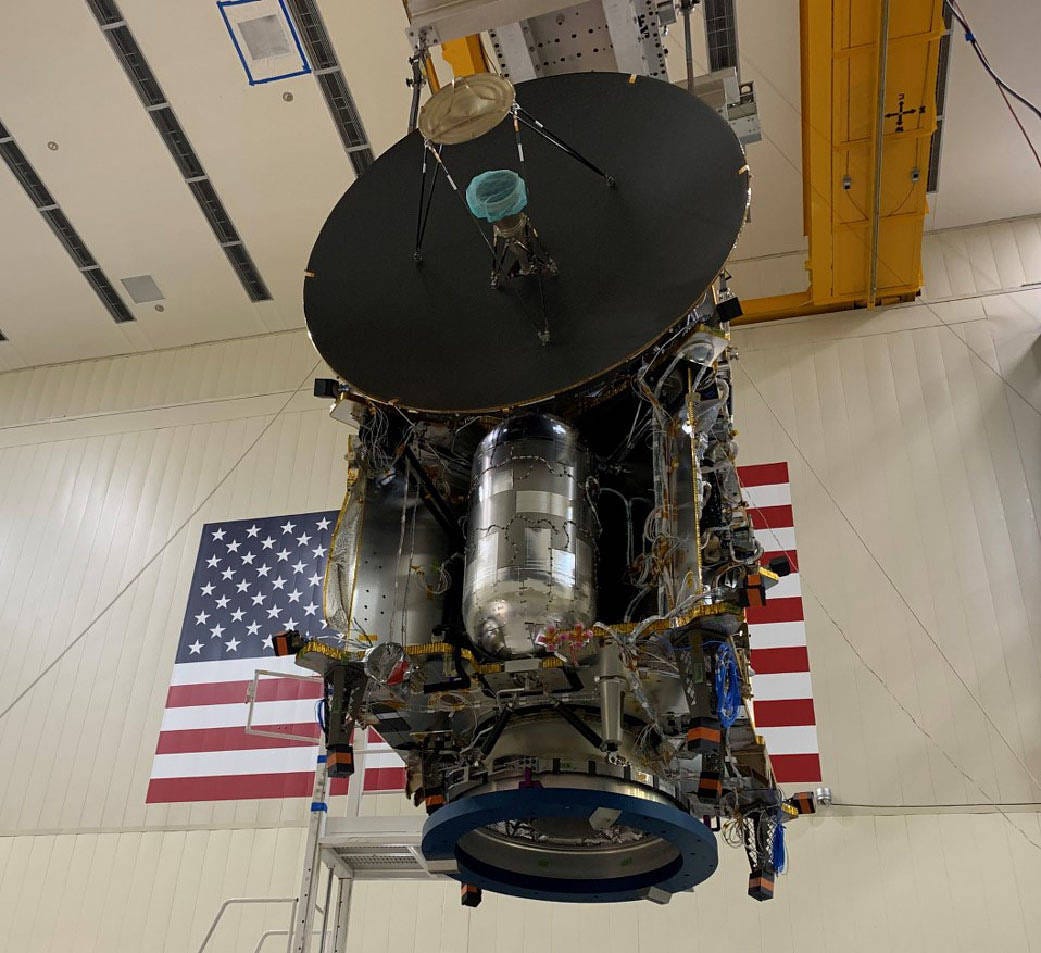

Lucy, which is named for the famous fossil of a human ancestor, is lowered into its environmental testing chamber at Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado.

Lucy engineers working on the spacecraft.

The idea of examining fossils is core to the mission's philosophy -- right down to its name. "Lucy" is derived from a hominid skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. The skeleton was dubbed Lucy because the Beatles' song Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds was playing in the scientists' camp after the find. Words from all four Beatles are contained on a plaque inside the spacecraft.

Though the early morning launch and separation was marked down as a success on Lucy's extensive to-do list, the spacecraft had to overcome one final, giant hurdle before it was ready to sail out of Earth's backyard. About one hour into its flight, the probe experienced "20 minutes of terror," as it unfurled its 24 foot wide decagonal solar panels.

The panels are critical to the spacecraft's success and will power Lucy during the 12-year journey toward the Trojans. They can supply about 500 watts of power -- about the same amount of energy necessary to run a washing machine, according to NASA. And Lucy will need every watt, because it'll be the farthest solar-powered spacecraft should it reach its destinations.

Lucy's complex trajectory and flyby dates

.SwRI/NASA

Ninety-one minutes after launch, the team acquired a signal from Lucy confirming the solar panels had deployed. "Things were splendid today," said Omar Baez, the senior launch director of NASA's Launch Services Program.

That means Lucy is alive and well and now there's a lot of ground to cover before it reaches its first object of interest: Donaldjohanson, a space rock positioned in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. That flyby will occur in April 2025.

From there, Lucy will swing toward the Trojans, reaching four worlds throughout 2027 and 2028 in the Greek camp, the swarm of rocks leading Jupiter in orbit. Another Earth flyby will help propel Lucy to its final targets, Patroclus and its binary companion Menoetius, in the Trojan camp trailing Jupiter in 2033. In total, the spacecraft will cover 4 billion miles.

Lucy's ambitious main mission won't necessarily end with Patroclus and Menoetius, either. The spacecraft's orbit will see it drift through the swarms for years to come. NASA has a good track record with extending missions -- but you'll have to keep your fingers crossed that everything goes well for the next decade.

First published on Oct. 16, 2021 at 4:13 a.m. PT.

Ninety-one minutes after launch, the team acquired a signal from Lucy confirming the solar panels had deployed. "Things were splendid today," said Omar Baez, the senior launch director of NASA's Launch Services Program.

That means Lucy is alive and well and now there's a lot of ground to cover before it reaches its first object of interest: Donaldjohanson, a space rock positioned in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. That flyby will occur in April 2025.

From there, Lucy will swing toward the Trojans, reaching four worlds throughout 2027 and 2028 in the Greek camp, the swarm of rocks leading Jupiter in orbit. Another Earth flyby will help propel Lucy to its final targets, Patroclus and its binary companion Menoetius, in the Trojan camp trailing Jupiter in 2033. In total, the spacecraft will cover 4 billion miles.

Lucy's ambitious main mission won't necessarily end with Patroclus and Menoetius, either. The spacecraft's orbit will see it drift through the swarms for years to come. NASA has a good track record with extending missions -- but you'll have to keep your fingers crossed that everything goes well for the next decade.

First published on Oct. 16, 2021 at 4:13 a.m. PT.

In green, you see the leading and trailing swarms of Jupiter Trojans. That's where Lucy is headed.

NASANASA's Lucy mission: 20 minutes of terror will define the next 12 years

One of Lucy's engineers takes us behind the scenes of the momentous mission to the Trojan asteroids that share Jupiter's orbit around the sun.

Monisha Ravisetti

Oct. 16, 2021

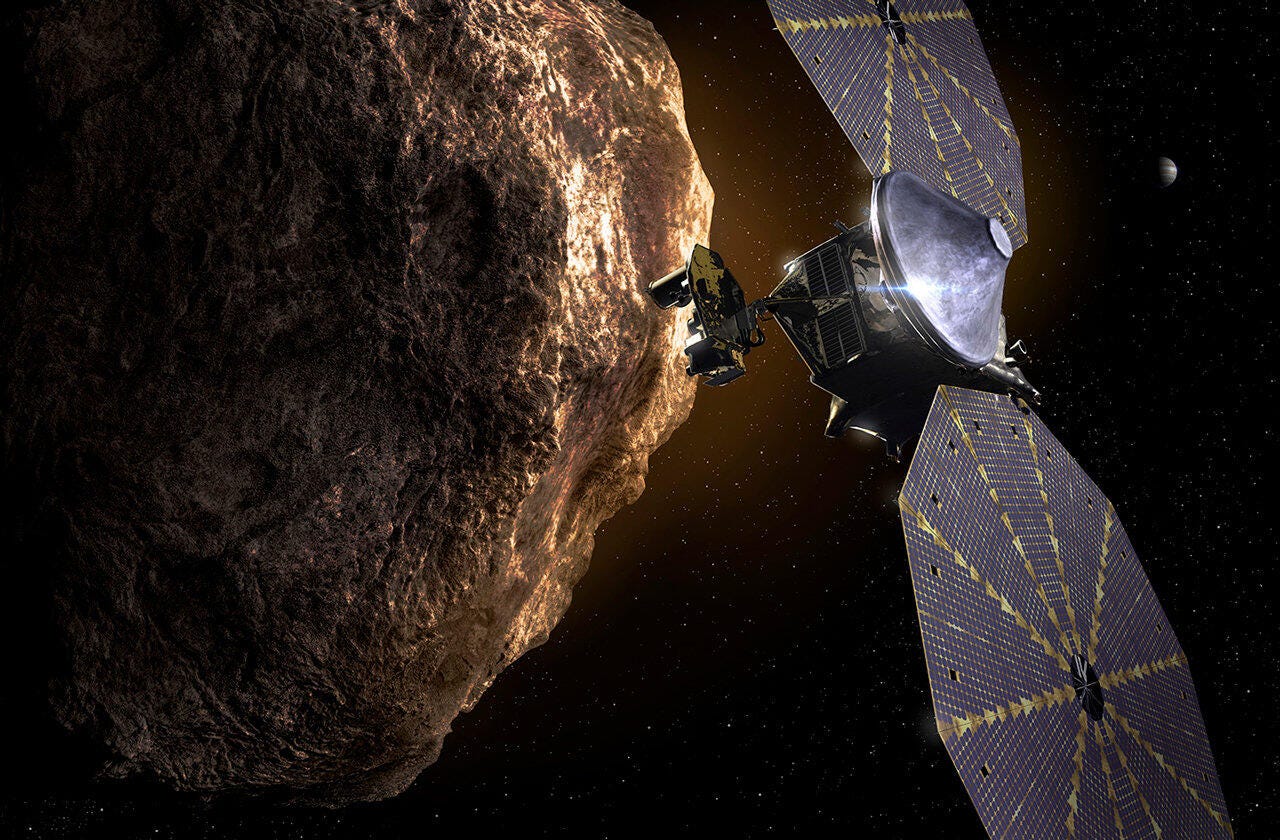

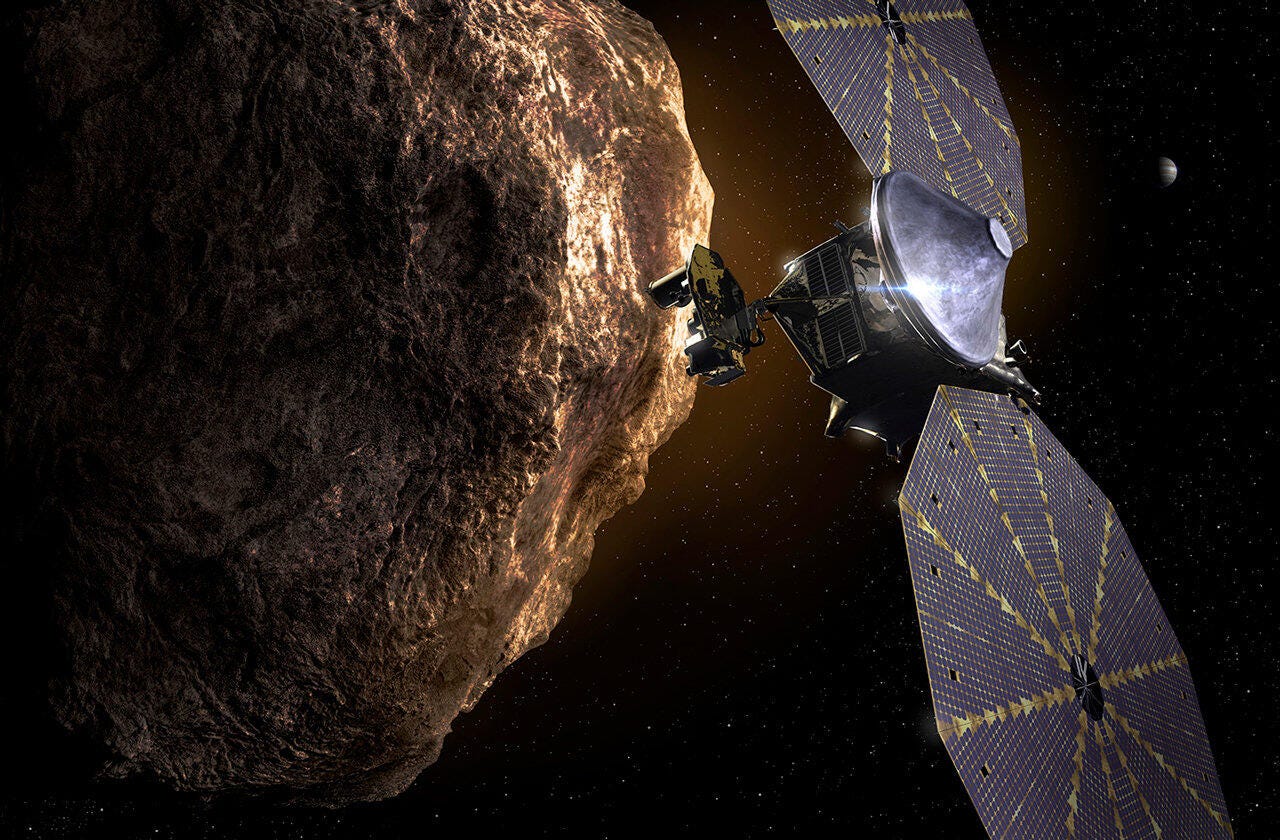

Lucy will journey to eight asteroids over the next dozen years.

Illustration by Lockheed Martin

Editor's note: This story was originally published Friday, Oct. 15. On Saturday, Lucy's liftoff was a success, with the principal investigator of the mission calling the launch "truly awesome, in the old-fashioned meaning of the word." Lucy has safely unfurled her solar arrays, too. Do read on, though, for unique insight into Lucy's launch and mission...

On Saturday, NASA's Lucy spacecraft will become the first-ever probe launched toward the Trojan asteroids, eons-old rocks trapped in Jupiter's orbit. These rocks are the fossilized building blocks of our solar system and may hold records of the giant planets' evolution.

But for Lucy to make history and ultimately unlock secrets of our corner of the universe, this weekend's liftoff must be flawless. Given the spacecraft's unique trajectory -- billions of miles will be covered over a dozen years by harnessing the power of the sun -- there are a few checkpoints poised to keep mission specialists on their toes.

As outsiders, we usually only stare in astonishment as rockets launch, engulfed in flame and smoke. But there's much more to Lucy's success than just its fiery departure from Earth. I spoke with one of the spacecraft's engineers from Lockheed Martin and got the inside scoop on what milestones her team will be watching for during liftoff.

Editor's note: This story was originally published Friday, Oct. 15. On Saturday, Lucy's liftoff was a success, with the principal investigator of the mission calling the launch "truly awesome, in the old-fashioned meaning of the word." Lucy has safely unfurled her solar arrays, too. Do read on, though, for unique insight into Lucy's launch and mission...

On Saturday, NASA's Lucy spacecraft will become the first-ever probe launched toward the Trojan asteroids, eons-old rocks trapped in Jupiter's orbit. These rocks are the fossilized building blocks of our solar system and may hold records of the giant planets' evolution.

But for Lucy to make history and ultimately unlock secrets of our corner of the universe, this weekend's liftoff must be flawless. Given the spacecraft's unique trajectory -- billions of miles will be covered over a dozen years by harnessing the power of the sun -- there are a few checkpoints poised to keep mission specialists on their toes.

As outsiders, we usually only stare in astonishment as rockets launch, engulfed in flame and smoke. But there's much more to Lucy's success than just its fiery departure from Earth. I spoke with one of the spacecraft's engineers from Lockheed Martin and got the inside scoop on what milestones her team will be watching for during liftoff.

Here's the launch sequence from the eyes of NASA.

"When the rocket lifts off from the ground, that's very visual and exciting," said Emily Gramlich, a system integration and test engineer at Lockheed Martin and a Lucy mission specialist. "As the rocket ascends, we go through the atmosphere."

During that phase, Lucy will reach its maximum speed and pressure. "Then," Gramlich continued, "we have separation from the boosters and then the bearing will deploy and open us up to outer space."

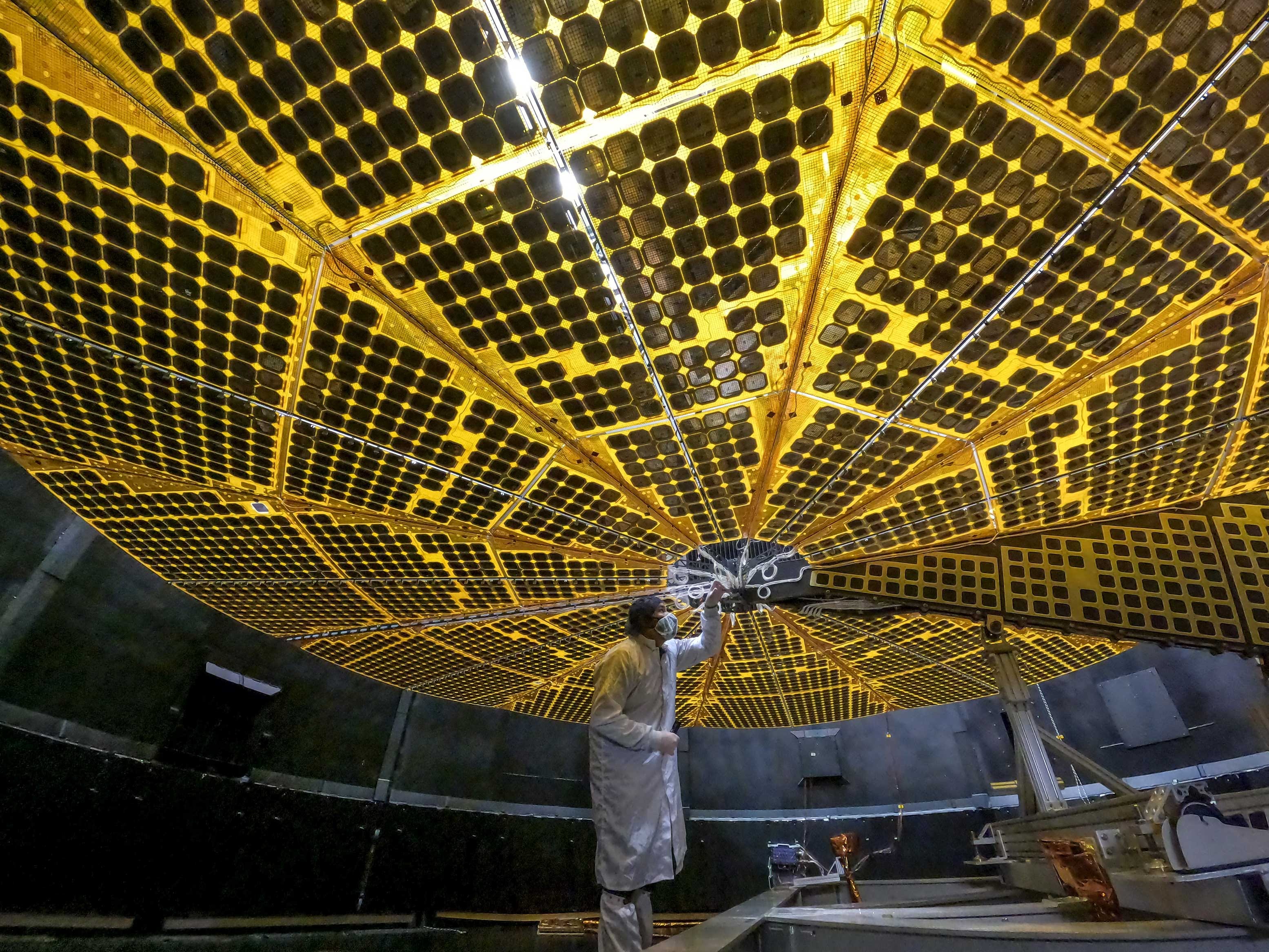

A researcher works on one of Lucy's folded solar arrays.

Lockheed Martin

Lucy's epic launch doesn't end there. Arguably the most crucial part of the launch pattern will be the unfurling of the spacecraft's two solar arrays after its 62-mile (100-km) journey up into space.

When fully open, the arrays together reach the height of a five-story building. "They are enormous," Gramlich said. It will take about 20 minutes to completely extend them from their origami-like folds.

They're so large because Jupiter's orbit, where Lucy is headed, is so far from the sun. And Lucy will need all the sun power it can get to travel those 530 million miles (853 million km).

"These 20 minutes will determine if the rest of the 12-year mission will be a success," NASA planetary scientist and principal investigator of the Lucy mission, Hal Levison, said in a statement.

"Mars landers have their seven minutes of terror, we have this," he said.

After the solar arrays stretch out in their entirety, Lucy will have another vital task: It must adjust itself so the sun can shine onto all the solar panels that make up the two arrays. Without sun, the solar panels cannot provide power. Without power, the mission is over.

"Once we've done that," Gramlich said, "the spacecraft will then move itself a little bit more so that it can also point its antenna down at the Earth, so we can get our initial acquisition."

Let me repeat that last bit: "initial acquisition." That means every step up to that point is pre-programmed. That's right. No one will be controlling the spacecraft during its most crucial moments. Each precise movement has already been coded into its software.

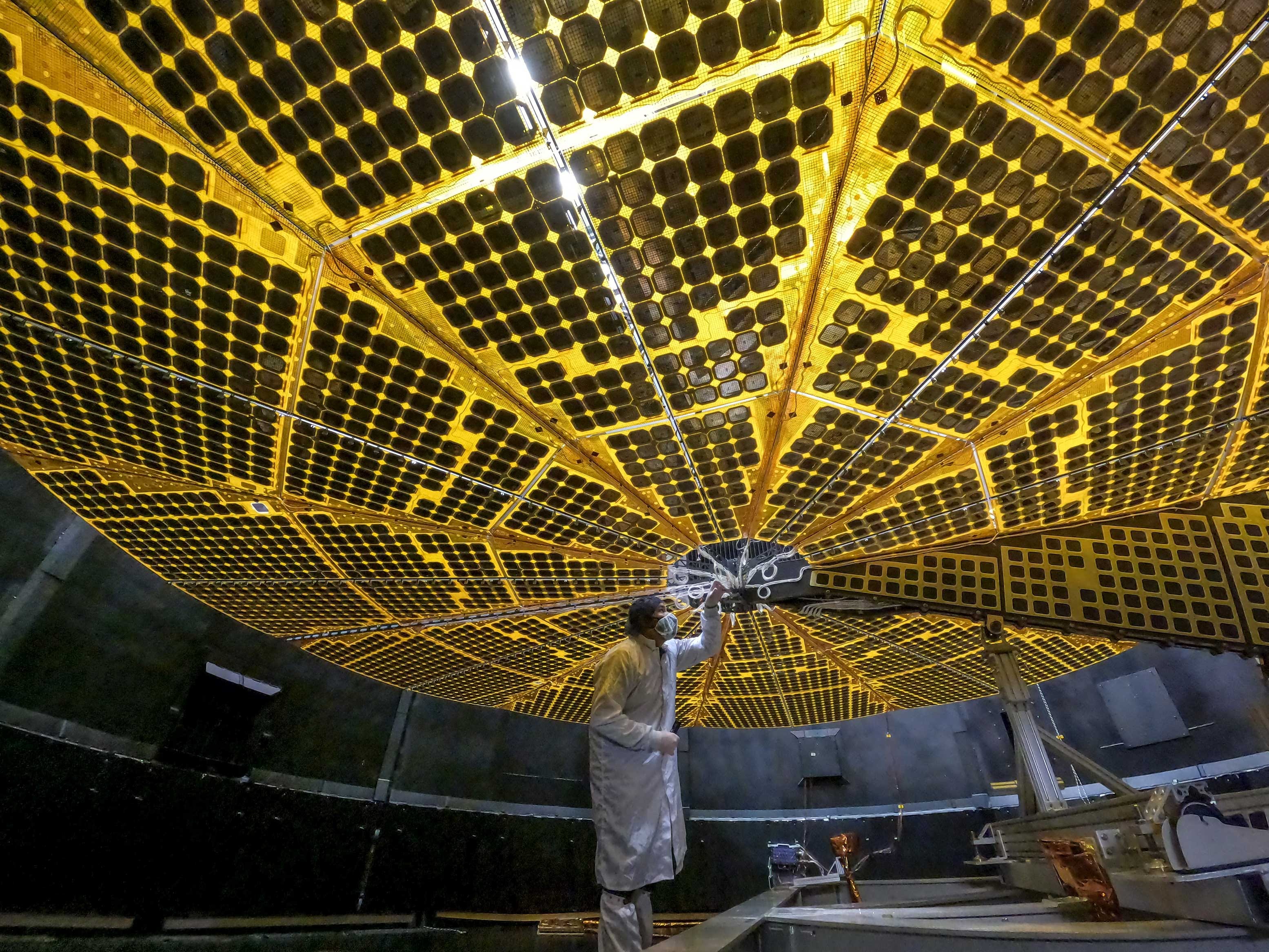

One of Lucy's solar arrays, fully stretched out.

Lucy's epic launch doesn't end there. Arguably the most crucial part of the launch pattern will be the unfurling of the spacecraft's two solar arrays after its 62-mile (100-km) journey up into space.

When fully open, the arrays together reach the height of a five-story building. "They are enormous," Gramlich said. It will take about 20 minutes to completely extend them from their origami-like folds.

They're so large because Jupiter's orbit, where Lucy is headed, is so far from the sun. And Lucy will need all the sun power it can get to travel those 530 million miles (853 million km).

"These 20 minutes will determine if the rest of the 12-year mission will be a success," NASA planetary scientist and principal investigator of the Lucy mission, Hal Levison, said in a statement.

"Mars landers have their seven minutes of terror, we have this," he said.

After the solar arrays stretch out in their entirety, Lucy will have another vital task: It must adjust itself so the sun can shine onto all the solar panels that make up the two arrays. Without sun, the solar panels cannot provide power. Without power, the mission is over.

"Once we've done that," Gramlich said, "the spacecraft will then move itself a little bit more so that it can also point its antenna down at the Earth, so we can get our initial acquisition."

Let me repeat that last bit: "initial acquisition." That means every step up to that point is pre-programmed. That's right. No one will be controlling the spacecraft during its most crucial moments. Each precise movement has already been coded into its software.

One of Lucy's solar arrays, fully stretched out.

Lockheed Martin

"Lucy has been encapsulated since last week and so we have not seen it … other than through a small access window," Gramlich said. "The next time it will be open is out in outer space."

NASA engineers will just have to sit tight and keep their fingers crossed until Lucy finds its cosmic footing.

"Lucy has been encapsulated since last week and so we have not seen it … other than through a small access window," Gramlich said. "The next time it will be open is out in outer space."

NASA engineers will just have to sit tight and keep their fingers crossed until Lucy finds its cosmic footing.

Lucy's bootcamp

You name it, Lucy's been through it. Several times.

"We do an acoustic test and a vibration test in a large building on the Waterton campus," said Gramlich referring to Lockheed Martin's testing grounds in Colorado. "We shake the spacecraft really hard and then we blast it with sound to simulate mostly the launch."

The most physically intense part of Lucy's 12-year journey, she said, will be the launch happening this weekend. Once it's in space, the situation will become much calmer. But space has its own extremes, so the team has tried to ensure that Lucy will be shielded from those, too.

"We take the spacecraft and put it into a giant thermal chamber and run it through all the temperature ranges that it is going to see in space -- hot and cold, light and no light," Gramlich said.

Lucy, which is named for the famous fossil of a human ancestor, is lowered into its environmental testing chamber at Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado.

Lockheed Martin

Lucy's complexities aren't only in regard to its mechanics. The software piloting the metal space explorer has a sizable number of integral components, like the computer, thermometer, cameras and battery. Each one had to be tested over and over again.

Gramlich explained one important device on Lucy is the star tracker that helps with navigation similar to how the north star aids in deducing what direction we're facing.

"We have extra ground support equipment to simulate the star that it might be seeing," she said. "And to rotate those stars and make sure that the star tracker detects that the stars [actually] rotated on its little simulator."

Once Lucy stabilizes and beyond

"I am beyond excited to see Lucy lift off on Saturday," Gramlich said. "We have been working towards this launch date for a long time, and there are a lot of long hours in the pandemic, and I have been just extra energetic for the last few weeks."

If all goes well on NASA's launch day on Saturday, Lucy will continue on toward the Trojan asteroids at about 39,000 mph (62,764 kph). It will use Earth's gravitational pull as leverage during the long journey and visit seven of the prized ancient rocks. It'll also make a pit stop on another world between Mars and Jupiter.

During the expedition, Gramlich said the team will check up on Lucy about once every two weeks to input commands based on newly discovered information, such as photographs and spectroscopic data, about the asteroids that Lucy sends back to Earth. Each command will take about 55 minutes to reach the craft, she said.

Lucy's complexities aren't only in regard to its mechanics. The software piloting the metal space explorer has a sizable number of integral components, like the computer, thermometer, cameras and battery. Each one had to be tested over and over again.

Gramlich explained one important device on Lucy is the star tracker that helps with navigation similar to how the north star aids in deducing what direction we're facing.

"We have extra ground support equipment to simulate the star that it might be seeing," she said. "And to rotate those stars and make sure that the star tracker detects that the stars [actually] rotated on its little simulator."

Once Lucy stabilizes and beyond

"I am beyond excited to see Lucy lift off on Saturday," Gramlich said. "We have been working towards this launch date for a long time, and there are a lot of long hours in the pandemic, and I have been just extra energetic for the last few weeks."

If all goes well on NASA's launch day on Saturday, Lucy will continue on toward the Trojan asteroids at about 39,000 mph (62,764 kph). It will use Earth's gravitational pull as leverage during the long journey and visit seven of the prized ancient rocks. It'll also make a pit stop on another world between Mars and Jupiter.

During the expedition, Gramlich said the team will check up on Lucy about once every two weeks to input commands based on newly discovered information, such as photographs and spectroscopic data, about the asteroids that Lucy sends back to Earth. Each command will take about 55 minutes to reach the craft, she said.

Lucy engineers working on the spacecraft.

Lockheed Martin

And after the mission wraps up next decade, the possibilities are endless.

"Our last flyby is in 2033," Gramlich said. "We will have done three Earth flybys by then, and have learned a lot about our trajectory and how to make it most efficient to continue exploring other asteroids."

Calling that an extended mission, Gramlich says Lucy's solar arrays can continue powering the spacecraft as it traverses through the solar system indefinitely. That means Lucy can theoretically continue sending information back about other forms of cosmic matter.

"The solar arrays that we have for Lucy are incredibly efficient and will allow us to operate the spacecraft for a long time," she said. "Even out at the distances of Jupiter. And the battery on board is also designed to be used and recharged."

But first, Lucy must get past its legendary launch.

"I am so honored that I was part of this team to see how much everybody cares and put into it," Gramlich said.

"We are just ready for a successful science mission to the Trojans."

Correction, 2:20 p.m. PT: An earlier version of this story misstated where one of the spacecraft's engineers works. Emily Gramlich works for Lockheed Martin. Also, the deck headline was changed to clarify that the Trojan asteroids share Jupiter's orbit.

First published on Oct. 15, 2021 at 5:00 a.m. PT.

And after the mission wraps up next decade, the possibilities are endless.

"Our last flyby is in 2033," Gramlich said. "We will have done three Earth flybys by then, and have learned a lot about our trajectory and how to make it most efficient to continue exploring other asteroids."

Calling that an extended mission, Gramlich says Lucy's solar arrays can continue powering the spacecraft as it traverses through the solar system indefinitely. That means Lucy can theoretically continue sending information back about other forms of cosmic matter.

"The solar arrays that we have for Lucy are incredibly efficient and will allow us to operate the spacecraft for a long time," she said. "Even out at the distances of Jupiter. And the battery on board is also designed to be used and recharged."

But first, Lucy must get past its legendary launch.

"I am so honored that I was part of this team to see how much everybody cares and put into it," Gramlich said.

"We are just ready for a successful science mission to the Trojans."

Correction, 2:20 p.m. PT: An earlier version of this story misstated where one of the spacecraft's engineers works. Emily Gramlich works for Lockheed Martin. Also, the deck headline was changed to clarify that the Trojan asteroids share Jupiter's orbit.

First published on Oct. 15, 2021 at 5:00 a.m. PT.

Lucy stands 13 feet (4 meters), nearly fully assembled in this photo.

Lockheed Martin

No comments:

Post a Comment