Devin Coldewey@techcrunch •October 1, 2021

Image Credits: IATSE

A dispute over working conditions at “new media” properties like Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV and others may shut down productions across the country if a strike vote by the union succeeds. Thousands of workers on and off set claim they are not receiving appropriate wages, breaks, safety measures and other needs due to a contractual loophole exempting these companies from established film and TV production labor standards.

The conflict has been widely covered in the entertainment press, with celebrities and studios voicing their support and countless workers sharing horror stories from jobs on these productions.

The issue, as explained by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, or IATSE, is a 2009 agreement made when companies like Netflix were just starting to get into original productions and didn’t have the kind of labor infrastructure that established studios did. The economics of these “new media” companies being “uncertain,” it was decided that “greater flexibility” would be afforded to them in on-set matters where union rules might impede new and untested entrants.

But that same agreement noted that once these services became more economically viable, then a new agreement should take its place acknowledging that. That time, the IATSE says, has come.

And who could possibly disagree? Netflix is now an industry powerhouse, and billions are being spent by Disney, Apple, and Amazon on some of the most high-profile media productions ever attempted. Yet because they are “new media,” the gaffers and grips on, say, something like the next season of Jack Ryan or Bridgerton don’t have the same guarantees of lunch breaks, hour limits, or proper scale wages as an “old media” production. (Note: I originally listed the Lord of the Rings as an example but this was poorly chosen, as it is a New Zealand-based production and not using IATSE union workers.)

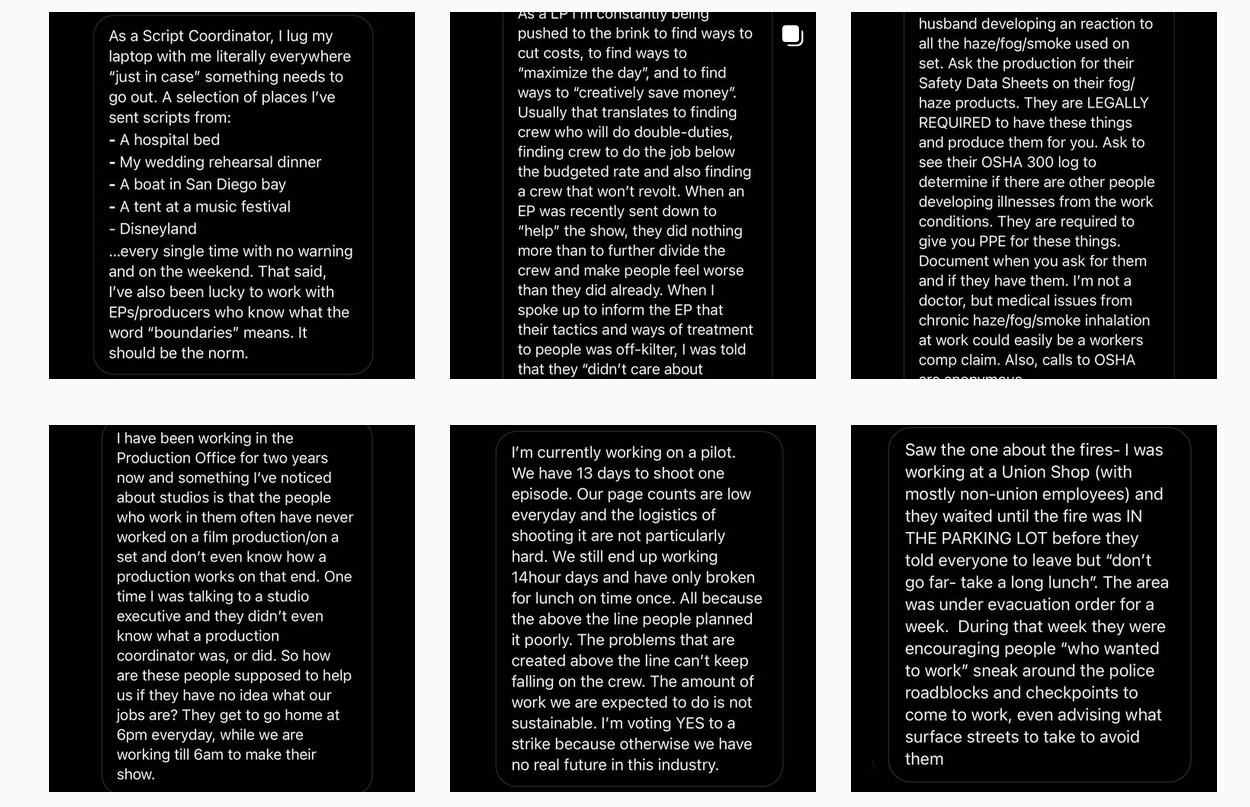

Image Credits: IA_stories / Instagram

That’s not to say that every production under these companies is hell — a lot depends on the producers — but the lack of guarantees has produced what many workers describe as systemic exploitation. It’s taken for granted that they will work longer hours than they are officially paid for, skip holidays and weekends, and so on, while earning less than they would for equivalent work on a production under, say, Universal or A24.

Much ink has been spilled on the huge production efforts of these companies, dropping billions to compete with one another over lucrative subscribers. Each company has dozens of shows being produced simultaneously and on breakneck schedule in order to satisfy the seemingly bottomless demand for content. If we don’t get a new Stranger Things season in time, there’s a good chance something will become “the new Stranger Things” and eat Netflix’s lunch, or rather popcorn.

Comparatively little has been written in the tech world about the human cost of these productions — after all, that’s more on the “entertainment” beat. But it’s par for the course with tech companies to claim the benefits of “innovation” while washing their hands of the repercussions; hardly a week goes by that we don’t hear about some horrible new consequence due to a feature or policy at Facebook, Google, Amazon, Uber, DoorDash or any number of other companies.

It’s not surprising to hear that some of these same companies are fostering an exploitative work environment — many of them rely on one already!

At any rate, negotiations between the IATSE and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers have stalled and the union has formally asked its workers to vote on whether to initiate a strike. If it’s a “yes” when the votes are counted in a few days, there will probably be one last chance for “new media” to make a satisfactory proposal before a huge number of productions are halted.

“We are united in demanding more human working conditions across the industry,” said IATSE president Matthew Loeb in a press release today. “If the mega-corporations that make up the AMPTP remain unwilling to address our core priorities and treat workers with human dignity, it is going to take the combined solidarity of all of us to change their minds.”

Certainly almost everyone involved would prefer not to have to strike, though it would be an impressive demonstration of organized labor’s power to disrupt a plainly hostile industry. Here’s hoping negotiations succeed at last and the production professionals being trodden on by this new crop of media overlords get the breaks they deserve.

Stars like Seth Rogen are backing a strike that could bring Hollywood to a halt.

Here's why.

Marco della Cava, USA TODAY

Fri, October 1, 2021,

OK, entertainment junkies, be prepared to go into withdrawal.

Just when COVID-19 helped us develop a newfound appreciation for – if not an outright dependence on – small- and big-screen entertainment, an industry strike may cause production to grind to a halt.

Unionized workers in charge of rigging lights, doing hair, making sets and just about everything else non-acting related will vote today whether to walk off the job. At issue are better working conditions, say leaders of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, or IATSE.

"How am I supposed to have a family while working 12+ hours a day (even longer when you add commuting)?" wrote would-be striker Kirsten Thorson on Instagram. "I love my job in the film industry but the industry doesn't love me back."

There are hints that some showrunners and directors are already heeding the complaints of crews.

On the Instagram account IATSE Stories, where members can post comments anonymously, one person wrote that "the director on the show I'm on follows this page and after reading how the crew gets treated, has made it a POINT to wrap before we hit 10hrs everyday, not even 12."deserve better,"

Seth Rogen, seen here presenting outstanding supporting actress in a comedy at the 73rd Emmy Awards, has spoken out in support of unionized Hollywood workers. "Our films and movies literally would not exist without our crews, and our crews deserve better," he tweeted.

Top actors are coming out in support of the possible strike, knowing that their jobs wouldn't exist without the armies behind them. And most are themselves part of their own union, the Screen Actors Guild.

"I just spent 9 months working with an incredibly hard working crew of film makers through very challenging conditions," Ben Stiller wrote on Twitter. "Totally support them in fighting for better conditions."

But supporting Hollywood crews does not mean all productions would stop. First off, there are a number of union contracts that are still in effect for another year, such as the one covering pay services such as HBO.

The contract that expired several months ago and led to this negotiation stalemate is focused in part on streaming services such as Netflix, who were issued more generous terms because the future of such services wasn't known back when the ink dried on IATSE's New Media deal in 2009.

And second, a shutdown could still be avoided, given what's at stake for producers and workers alike, says Thomas Lenz, an adjunct lecturer at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law and partner at Pasadena-based Atkinson, Andelson, Loya, Ruud & Romo.

"A 'yes' vote from union members puts them in a good bargaining position, something they can deploy if they need to," says Lenz. "Producers don't really want a disruption in the product they put out, and workers don't want to go long without pay. They could get back to the bargaining table."

We break down the plot:

Q: Which workers are ready to walk?

A: For months, the production workers union has been trying to negotiate a new three-year contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers for its 150,000 workers. These include cinematographers, costumers, script supervisors and grips – essentially, the critical folks who allow the stars to shine. The union has never before gone on strike. If it did this time, an estimated 60,000 of those members currently on jobs are expected to stop working.

The parties have been talking for a while. The current contract was set to expire July 31, but as talks dragged on it was extended to Sept 10. Negotiations for a new three-year deal continued after that, eventually leading to this tense moment.

Lenz says the pandemic's impact on work/life balance is also a factor. "If you're working 10- and 12-hour days routinely, the pandemic may now have caused you to reassess your whole lifestyle and decide if you want to work the same way as you did in the past," he says.

Q: What does the union want?

A: IATSE wants better working conditions and salaries, while AMPTP feels the demands are too financially onerous for an industry that's still reeling from the pandemic. A letter written by IATSE president Matthew Loeb says the aim is “more humane working conditions across the industry, including reasonable rest during and between workdays and on the weekend, equitable pay on streaming productions, and a livable wage floor.” Under the current IATSE New Media deal, for example, streaming services with fewer than 20 million subscribers pay lower wages. Also on the table: making Martin Luther King Jr. Day a holiday for union workers.

"Employers, such as the producers guild here, go into things looking at everything as a cost item," says Lenz. "But the times are a bit different now. Look at all the social justice protests over the past year and something like giving people MLK Day off makes sense. Most employers are waking up to that."

Many pay TV programs would not be affected by a strike of production-side workers, as contracts between producers and the unions differ depending on the type of content in question. HBO's "Succession," for example, would not be in jeopardy from a strike.

Q: Which productions will suffer?

A: Movies, network TV shows and Netflix productions would halt as they fall under the now-expired contract. That means any television series or reality show currently in production might be delivering repeat episodes to fans later this year or early next year.

But a number of popular premium-cable productions – and so-called low-budget theatrical fare – wouldn't be stalled because that union contract is good until the end of 2022. Commercials also are safe. IATSE's agreement with the Association of Independent Commercial Producers runs through Sept. 30, 2022.

“If you are working on commercials or for HBO, Showtime, Starz, Cinemax, BET or another company that has a contract still in effect – you must keep working,” IATSE informed members working on productions for those companies earlier this week. “You will not be a scab!”

Q: What do Hollywood stars think?

A: Would-be strikers have support on social media. Seth Rogen tweeted, "Our films and movies literally would not exist without our crews, and our crews deserve better." "Grace and Frankie” co-stars Lily Tomlin and Jane Fonda shared a photo of themselves on Instagram with raised fists while wearing union T-shirts. Bradley Whitford tweeted that negotiators for AMPTP "refuse to even discuss guaranteed meal breaks or 10 hour turnarounds. That's nuts. If you make a living in front of a camera, now is the time to speak for the people who make it possible."

Q: Is this a new dispute?

A: Consider it another episode in a long-running series. In 1945, 10,500 members of the Confederation of Studio Unions went on strike, shutting down production on the David O. Selznick epic “Duel in the Sun,” starring Gregory Peck. Months went by without a resolution, culminating in riots in front of Warner Bros. studios. More recently, the Writers Guild of America struck in late 2007 for a larger percentage of show profits. The 14-week standoff halted production of TV and movies. After its resolution, economists estimated that the strike cost the Los Angeles economy more than $1 billion.

Q: What happens now?

A: IATSE needs at least 75% of its membership to vote yes to call the strike. Votes are expected to come in over the weekend, and the union could in theory call a strike as early as Monday. Negotiations are likely to continue behind the scenes even as the union mulls officially pulling its workers off the job.

There is an economic incentive to work out a deal. A recent report from the Motion Picture Association of America, using Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2016, indicated that the film and TV industry produces more than 2 million high-paying jobs that in turn funnel nearly $50 billion annually to businesses wherever content is being created.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hollywood strike vote: What could it mean for your favorite TV shows?

“Unsustainable and Unhealthy”: As IATSE Workers Go Public, Pressure Mounts on Studios Amid Looming Strike

As film and TV production ramps up after pandemic shutdowns and this year’s "Great Resignation" ripples across the broader job market, Hollywood crewmembers say over-12-hour workdays, short rest periods and under-$18-an-hour rates are "just cruel."

BY KATIE KILKENNY

OCTOBER 2, 2021

Makeup artist Kristina Frisch learned quickly that COVID-19 hadn’t slowed the pace of work in film and television production. After accepting her first full-time job following pandemic-related shutdowns, she discovered the gig would entail working six-day weeks for the entire shoot and never being able to break for lunch (she could eat while working). Then, during the shoot, “I went five days without seeing my children,” Frisch says, a new record for her. Overall, after quarantine, “It was like, we got shut down, so we now have to work longer and harder.”

Kristina Frisch, photographed on October 1 in Los Angeles.

For months, crewmembers have shared stories like this one on social media, detailing long hours, low wages and grueling work conditions in today’s production environment, against the backdrop of new contract negotiations. Since May, the major crew union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), has been hammering out details for a new Basic Agreement with the Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

Related Stories

BUSINESS

Directors Guild Names Negotiations Committee Leaders

BUSINESS

33 New York State Senators Criticize "Outrageous" IATSE Work Conditions, Ask Studios to Negotiate In "Good Faith"

Union leaders have been advocating for more substantial rest periods, higher minimum rates for the lowest-paid crafts, and more streaming compensation and resources for their health and pension plan. Those talks broke down in mid-September, and this weekend, tens of thousands of IATSE members are voting on whether to authorize their international president, Matthew Loeb, to potentially call a strike against the film and television industry. For their part, the AMPTP has said that the union walked away from a “deal-closing comprehensive proposal” that addressed its top concerns. A strong vote in favor of authorization could give union negotiators more leverage in talks, while an overall “no” vote could jeopardize their position.

Colby Bachiller, photographed on September 29 in Los Angeles

However the vote pans out, this negotiation period has inspired crewmembers to get increasingly candid about work conditions. As a result, “I think [the larger industry is] finally paying attention,” says script coordinator and Local 871 member Colby Bachiller. “Even before the pandemic, we knew how the rates and the hours were unlivable, unsustainable and unhealthy — but now they’re just cruel.” IATSE members are getting more specific about their concerns, too, raising the alarm about skipped meal breaks, extensive workdays, short rest periods and living standards on their union’s minimum rates. (The AMPTP’s proposal to IATSE included improved rest periods for certain postproduction workers and crewmembers working on first-season TV shows, and a 10-19 percent increase in minimum rates for low-paid crafts, it has said.)

Thanks in part to the popular Instagram account IA Stories, which shares mostly anonymous tales from crewmembers, IATSE workers have become especially vocal about the toll of over-12-hour workdays. Though some productions initially gestured toward trying to implement a 10-hour day, as recommended by the industry’s top guilds when production restarted during the pandemic, “it seemed like a lot of that good-faith stuff did not hold up,” says property master Theresa Corvino, a member of Local 44. “I’ve seen dramatic shifts toward not taking meal breaks at all or meal breaks running hours behind; seeing 14-16 hour days on the regular when the soft promise was 10-hour days; seeing shows running what we refer to as ‘Fraturdays’ just about every weekend.” (“Fraturdays” refer to late Friday shoots that run into the early morning on Saturday, giving crewmembers less rest time before they return to work on Monday.)

Victor P. Bouzi, photographed on October 1 in Los Angeles.

Victor P. Bouzi, a sound mixer and Local 695 member, says of some jobs requiring 14- to 20-hour days for weeks, “That wasn’t always the case. This seems to be more of a drive just to get the product out since COVID with all these new streaming platforms that have come out.” One crewmember says they’re “constantly” asked to change time cards when it comes to turnaround invasions. A studio source says the AMPTP offered a daily 10-hour turnaround, with exceptions for feature postproduction, on-call employees and studio publicity, during negotiations. Fraturdays are still an “open item” in negotiations, this source says, adding that during night shoots, “clearly you’re going to have that situation.”

A lack of guaranteed meal breaks makes these long days even more taxing, according to some crewmembers. “I just worked on a feature in Atlanta where we never once had a lunch break. Not once did we have a lunch break for 40 shooting days,” says costumer and Local 705 member Eric Johnson. Union members claim that meal penalties, the fee productions pay when workers miss mandated meal periods, have become so affordable that productions bake them into budgets (Basic Agreement signatories have to pay members of at least some major IATSE locals between $7.50 and $13.50 per half hour after the missed mealtime). And while the extra meal-penalty compensation can be helpful to those with low pay, “after 10 years of [missed meals], you just can’t sustain that,” says Johnson. Some productions advocate for “rolling lunches” where workers step away briefly and/or fill in for one another during an uninterrupted workday so they can grab food, but crewmembers in certain roles — like those in the camera department — say that they can’t realistically leave or have someone else briefly assume their roles.

Eric Johnson, photographed on September 29 in Los Angeles.

On social media, IATSE members and their allies have advocated for guaranteed meal breaks. The studio source says the AMPTP offered an “alternative meal break solution,” with rolling lunches being just one of the options discussed, which was rejected. “We feel that people do have an opportunity to actually have a meal on productions by and large,” this studio source adds.

Workers say extra long hours that may have been sustainable when they were younger aren’t now. “When you’re 24 years old, it’s very different than when you’re 44 years old, how your body can handle all that,” says director of photography and Local 600 member Patti Lee, who previously worked as an electrician and gaffer. “You also see a lot of broken people at the end, in their older years.”

Individuals in some of IATSE’s lowest-paid roles say that, beyond long hours, they face additional struggles due to what they describe as unlivable pay. Currently, writers assistants, assistant production coordinators and art department coordinators make a contractual minimum of $16 an hour or a little bit above, while script coordinators make, at minimum, $17.64 an hour. While trying to learn how to make ends meet in her role, Bachiller remembers being advised by support-staff colleagues to, on Fridays, take “all the food that was about to expire from the kitchen and that would be our groceries for the weekend.” She adds, “That was just considered normal, that was just part of paying your dues.” Alison Golub, a writers assistant and Local 871 member, counts herself lucky that she’s an L.A. native and can live at home — “because I can’t afford to pay rent.” A strike would be especially challenging for members in these roles, and Local 871 is currently putting together a program, potentially financed at least in part by a strike fund, to offer financial support to them in the event of a strike; at least one other Local is working on an economic relief program.

Concern over crewmembers’ working hours, rest periods and low wages isn’t new, and has been building steadily for years. According to one union insider who spoke on the condition of anonymity, the issues the union is fighting for this round of negotiations are “the same five or six issues that we have been talking [about] with our employers for a decade,” namely, low wages, long hours, rest periods, compensation from new media, and health and pension plan funding. (“There are some issues that both sides, producers and unions, want to resolve in negotiations,” the studio source counters. “At the end of the day, there have been deals made the last five or six rounds of negotiations, and clearly both sides, including the union, agreed to the contract, so they must have agreed to those lists of priorities.”) The 1997 death of second camera assistant Brent Lon Hershman in a car crash and the 2006 release of Haskell Wexler’s documentary on entertainment’s long working hours, Who Needs Sleep?, ignited similar conversations decades before. Members of the Motion Picture Editors Guild and the Costume Designers Guild have discussed a potential strike for years.

But IATSE members — whose union represents roles as disparate as studio publicists and lighting technicians — are “straight-up united” about these issues in 2021, says Bouzi. Citing the so-called “Great Resignation,” a term describing the recent nationwide surge in resignations across industries, Golub adds, “I think what’s going on in the film industry right now is indicative of what’s going on in the country as a whole.” She says, “I enjoy working in film and television but I also want to have a life outside of it and that’s not unreasonable to ask for.”

In recent days, the umbrella union, and the 36 Locals whose members will cast a ballot, have been keeping their constituency abreast of voting developments via email and text; Locals have also held informational town halls, and members have been using social media, phone-banking and car-painting to urge others to vote yes. In its communications with members, IATSE leaders are encouraging them to vote to authorize a strike and stressing that an authorization does not mean a strike will occur, but is instead a bargaining chip. The union insider notes that most members of their Local that they’ve talked to seem ready to vote yes, but a small number are still unsure. The AMPTP and IATSE do not yet have a set date to return to the negotiating table.

On set, crewmembers say they haven’t heard much chatter from management about a potential strike even as it looms over the industry, threatening productions nationwide. “You know things are being done in a different way than normal because there’s concerns about there being a strike, but nobody is coming out and saying, ‘We’re doing this because of a strike,'” says Corvino. Frisch says it’s strange to see fellow crewmembers wearing “IA Solidarity” T-shirts on set but few people around them talking or asking about it. “Everybody acts like something’s not happening until they absolutely have to deal with it,” she says, “which I understand, really, because you never know what way it’s going to go.”

No comments:

Post a Comment