A repurposed antidepressant might help treat COVID-19, a remarkable study found. The way this research was funded highlights a big problem—and bigger opportunity—in American science.

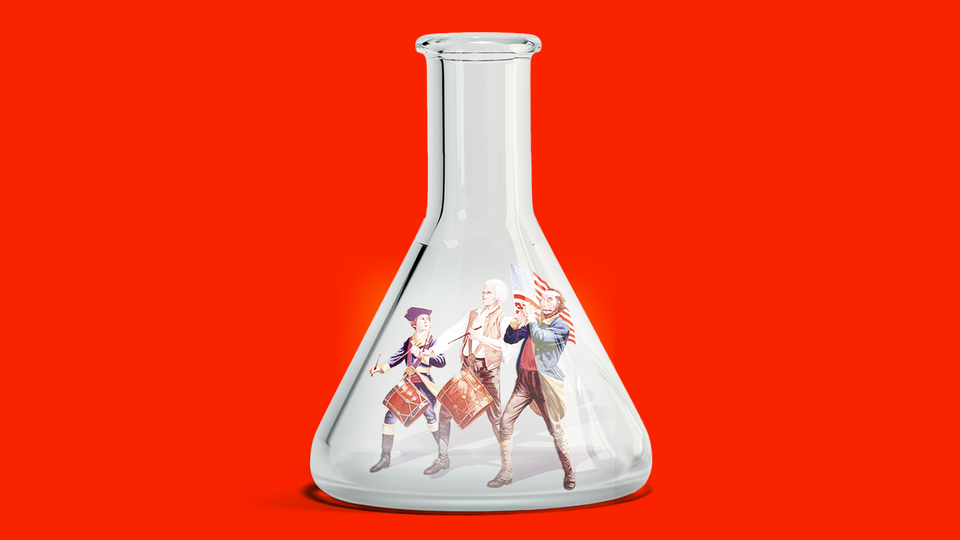

Getty; The Atlantic

NOVEMBER 5, 2021

About the author: Derek Thompson is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he writes about economics, technology, and the media. He is the author of Hit Makers and the host of the podcast Crazy/Genius.

Two stories in science are worth cheering right now: the amazing amount of knowledge humanity is gathering about COVID-19 and the quietly revolutionary ways we’re accelerating the pace of discovery.

First, the knowledge: Last week, a large clinical trial concluded that the cheap antidepressant drug fluvoxamine dramatically lowers the chance that people with COVID-19 will get hospitalized or die.

Researchers found that patients who took the drug for at least eight days saw a 91 percent reduction in death rate. Fluvoxamine, which has been used for decades to treat depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, also reduces inflammation, which alerted scientists to its potential to calm the immune-system storms caused by COVID-19. “This is exciting data,” Daniel Griffin, the chief of infectious disease at the health-care-provider network ProHealth New York, told The Wall Street Journal. “This may end up being standard of care.”

So far, so wonderful. But what makes this study even more remarkable were six boring-sounding words in the paper’s acknowledgments: “The trial was supported by FastGrants.”

What’s that?

Last year, in the chaotic opening innings of the coronavirus pandemic, the George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison, the CEO of the payment-processing company Stripe, co-founded a new program for quickly funding scientific research on COVID-19. They called it Fast Grants. Pulling together a small team of early-career scientists to vet several thousand ideas, they sent out the first round of money in about 48 hours. In 2020, they raised more than $50 million and awarded more than 260 grants that supported research on saliva-based tests, long COVID, and clinical trials for repurposed drugs—including fluvoxamine.

From the January/February 2021 issue: How science beat the virus

Like many new ideas, Fast Grants is an innovation embedded in a critique of the status quo.

Most scientific funding in the United States flows from federal agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. This funding is famously luxurious; the NIH and NSF allocate about $50 billion a year. It is also infamously laborious and slow. Scientists spend up to 40 percent of their time working on research grants rather than on research. And funding agencies sometimes take seven months (or longer) to review an application, respond, or request a resubmission. Anything we can do to accelerate the grant-application process could hugely increase the productivity of science.

The existing layers of bureaucracy have obvious costs in speed. They also have subtle costs in creativity. The NIH’s pre-grant peer-review process requires that many reviewers approve an application. This consensus-oriented style can be a check against novelty—what if one scientist sees extraordinary promise in a wacky idea but the rest of the board sees only its wackiness? The sheer amount of work required to get a grant also penalizes radical creativity. Many scientists, anticipating the turgidity and conservatism of the NIH’s approval system, apply for projects that they anticipate will appeal to the board rather than pour their energies into a truly new idea that, after a 500-day waiting period, might get rejected. This is happening in an academic industry where securing NIH funding can be make-or-break: Since the 1960s, doctoral programs have gotten longer and longer, while the share of Ph.D. holders getting tenure has declined by 40 percent.

Read: We need a new science of progress

Fast Grants aimed to solve the speed problem in several ways. Its application process was designed to take half an hour, and many funding decisions were made within a few days. This wasn’t business as usual. It was Operation Warp Speed for science.

In the past few years, I’ve had many conversations with entrepreneurs, researchers, and writers about the need for a new scientific revolution in this country. These thinkers have diagnosed several paradoxes in the current U.S. science system.

First is the trust paradox. People in professional circles like saying that we “believe the science,” but ironically, the scientific system doesn’t seem to put much confidence in real-life scientists. In a survey of researchers who received Fast Grants, almost 80 percent said that they would change their focus “a lot” if they could deploy their grant money however they liked; more than 60 percent said they would pursue work outside their field of expertise, against the norms of the NIH. “The current grant funding apparatus does not allow some of the best scientists in the world to pursue the research agendas that they themselves think are best,” Collison, Cowen, and the UC Berkeley scientist Patrick Hsu wrote in the online publication Future in June. So major funders have placed researchers in the awkward position of being both celebrated by people who say they love the institution of science and constrained by the actual institution of science.

Read: How public health took part in its own downfall

Second, there is a specialization paradox. Despite considerable domain specialization in the sciences, individual scientists cannot focus enough on doing hard research in their chosen field.

Since 1970, the number of years the average Ph.D. student in the biosciences spends in graduate school has grown from a little more than five years to almost eight years. Producing experts is taking longer, and those experts are getting less productive. In the famous paper “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?,” the Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom and his colleagues found that research productivity has declined sharply across the board since the 1970s. Research from the University of Chicago scholar James Evans has found that as the number of researchers has grown, progress has slowed down in some fields, perhaps because scientists are so overwhelmed by the glut of information they have to process that they’re clustering around the same safe subjects and citing the same few papers.

But in the bigger picture, today’s scientists can’t really specialize in science, because so many of them are forced to devote at least one day a week to begging for money. In the Fast Grants survey, a majority of respondents said they spend “more than one quarter of their time on grant applications.” This is absurd. It’s the height of irrationality, wastefulness, or both that the U.S. education system takes great pains to train scientists to be monkish specialists, only to dump them into an arms race for scarce funding that elbows out the work of doing science.

A third feature of American science is the experimentation paradox: The scientific revolution, which still inspires today’s research, extolled the virtues of experiments. But our scientific institutions are weirdly averse to them. The research establishment created after World War II concentrated scientific funding at the federal level. Institutions such as the NIH and NSF finance wonderful work, but they are neither nimble nor innovative, and the economist Cowen got the idea for Fast Grants by observing their sluggishness at the beginning of the pandemic. Many science reformers propose spicing things up with new lotteries that offer lavish rewards for major breakthroughs, or giving unlimited and unconditional funding to superstars in certain domains. “We need a better science of science,” the writer José Luis Ricón has argued. “The scientific method needs to examine the social practice of science as well, and this should involve funders doing more experiments to see what works.” In other words, we ought to let a thousand Fast Grants–style initiatives bloom, track their long-term productivity, and determine whether there are better ways to finance the sort of scientific breakthroughs that can change the course of history.

Four hundred years ago, the first scientific revolution overthrew old ways of looking at the world and embraced experimentation over tradition. We could use a similar revolution today. The U.S. relies on a fleet of scientific agencies—the CDC, FDA, NIH, and NSF—that are decades old and that, in many cases, act their age. The CDC publishes excellent research, but it utterly failed to respond quickly and adequately in the face of a national emergency. The FDA protects Americans from some terrible medical products, but its protectiveness also deprives Americans of some very good and urgently needed products. The NIH and NSF fund a lot of brilliant research, but their hegemony over scientific funding makes it hard to know whether we could be doing much, much better.

American science needs more science. That means, above all, that we need more experiments. We shouldn’t have to depend on 20th-century institutions to guide 21st-century progress. The lesson of Fast Grants is that we don’t have to.

NOVEMBER 5, 2021

About the author: Derek Thompson is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he writes about economics, technology, and the media. He is the author of Hit Makers and the host of the podcast Crazy/Genius.

Two stories in science are worth cheering right now: the amazing amount of knowledge humanity is gathering about COVID-19 and the quietly revolutionary ways we’re accelerating the pace of discovery.

First, the knowledge: Last week, a large clinical trial concluded that the cheap antidepressant drug fluvoxamine dramatically lowers the chance that people with COVID-19 will get hospitalized or die.

Researchers found that patients who took the drug for at least eight days saw a 91 percent reduction in death rate. Fluvoxamine, which has been used for decades to treat depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, also reduces inflammation, which alerted scientists to its potential to calm the immune-system storms caused by COVID-19. “This is exciting data,” Daniel Griffin, the chief of infectious disease at the health-care-provider network ProHealth New York, told The Wall Street Journal. “This may end up being standard of care.”

So far, so wonderful. But what makes this study even more remarkable were six boring-sounding words in the paper’s acknowledgments: “The trial was supported by FastGrants.”

What’s that?

Last year, in the chaotic opening innings of the coronavirus pandemic, the George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison, the CEO of the payment-processing company Stripe, co-founded a new program for quickly funding scientific research on COVID-19. They called it Fast Grants. Pulling together a small team of early-career scientists to vet several thousand ideas, they sent out the first round of money in about 48 hours. In 2020, they raised more than $50 million and awarded more than 260 grants that supported research on saliva-based tests, long COVID, and clinical trials for repurposed drugs—including fluvoxamine.

From the January/February 2021 issue: How science beat the virus

Like many new ideas, Fast Grants is an innovation embedded in a critique of the status quo.

Most scientific funding in the United States flows from federal agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. This funding is famously luxurious; the NIH and NSF allocate about $50 billion a year. It is also infamously laborious and slow. Scientists spend up to 40 percent of their time working on research grants rather than on research. And funding agencies sometimes take seven months (or longer) to review an application, respond, or request a resubmission. Anything we can do to accelerate the grant-application process could hugely increase the productivity of science.

The existing layers of bureaucracy have obvious costs in speed. They also have subtle costs in creativity. The NIH’s pre-grant peer-review process requires that many reviewers approve an application. This consensus-oriented style can be a check against novelty—what if one scientist sees extraordinary promise in a wacky idea but the rest of the board sees only its wackiness? The sheer amount of work required to get a grant also penalizes radical creativity. Many scientists, anticipating the turgidity and conservatism of the NIH’s approval system, apply for projects that they anticipate will appeal to the board rather than pour their energies into a truly new idea that, after a 500-day waiting period, might get rejected. This is happening in an academic industry where securing NIH funding can be make-or-break: Since the 1960s, doctoral programs have gotten longer and longer, while the share of Ph.D. holders getting tenure has declined by 40 percent.

Read: We need a new science of progress

Fast Grants aimed to solve the speed problem in several ways. Its application process was designed to take half an hour, and many funding decisions were made within a few days. This wasn’t business as usual. It was Operation Warp Speed for science.

In the past few years, I’ve had many conversations with entrepreneurs, researchers, and writers about the need for a new scientific revolution in this country. These thinkers have diagnosed several paradoxes in the current U.S. science system.

First is the trust paradox. People in professional circles like saying that we “believe the science,” but ironically, the scientific system doesn’t seem to put much confidence in real-life scientists. In a survey of researchers who received Fast Grants, almost 80 percent said that they would change their focus “a lot” if they could deploy their grant money however they liked; more than 60 percent said they would pursue work outside their field of expertise, against the norms of the NIH. “The current grant funding apparatus does not allow some of the best scientists in the world to pursue the research agendas that they themselves think are best,” Collison, Cowen, and the UC Berkeley scientist Patrick Hsu wrote in the online publication Future in June. So major funders have placed researchers in the awkward position of being both celebrated by people who say they love the institution of science and constrained by the actual institution of science.

Read: How public health took part in its own downfall

Second, there is a specialization paradox. Despite considerable domain specialization in the sciences, individual scientists cannot focus enough on doing hard research in their chosen field.

Since 1970, the number of years the average Ph.D. student in the biosciences spends in graduate school has grown from a little more than five years to almost eight years. Producing experts is taking longer, and those experts are getting less productive. In the famous paper “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?,” the Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom and his colleagues found that research productivity has declined sharply across the board since the 1970s. Research from the University of Chicago scholar James Evans has found that as the number of researchers has grown, progress has slowed down in some fields, perhaps because scientists are so overwhelmed by the glut of information they have to process that they’re clustering around the same safe subjects and citing the same few papers.

But in the bigger picture, today’s scientists can’t really specialize in science, because so many of them are forced to devote at least one day a week to begging for money. In the Fast Grants survey, a majority of respondents said they spend “more than one quarter of their time on grant applications.” This is absurd. It’s the height of irrationality, wastefulness, or both that the U.S. education system takes great pains to train scientists to be monkish specialists, only to dump them into an arms race for scarce funding that elbows out the work of doing science.

A third feature of American science is the experimentation paradox: The scientific revolution, which still inspires today’s research, extolled the virtues of experiments. But our scientific institutions are weirdly averse to them. The research establishment created after World War II concentrated scientific funding at the federal level. Institutions such as the NIH and NSF finance wonderful work, but they are neither nimble nor innovative, and the economist Cowen got the idea for Fast Grants by observing their sluggishness at the beginning of the pandemic. Many science reformers propose spicing things up with new lotteries that offer lavish rewards for major breakthroughs, or giving unlimited and unconditional funding to superstars in certain domains. “We need a better science of science,” the writer José Luis Ricón has argued. “The scientific method needs to examine the social practice of science as well, and this should involve funders doing more experiments to see what works.” In other words, we ought to let a thousand Fast Grants–style initiatives bloom, track their long-term productivity, and determine whether there are better ways to finance the sort of scientific breakthroughs that can change the course of history.

Four hundred years ago, the first scientific revolution overthrew old ways of looking at the world and embraced experimentation over tradition. We could use a similar revolution today. The U.S. relies on a fleet of scientific agencies—the CDC, FDA, NIH, and NSF—that are decades old and that, in many cases, act their age. The CDC publishes excellent research, but it utterly failed to respond quickly and adequately in the face of a national emergency. The FDA protects Americans from some terrible medical products, but its protectiveness also deprives Americans of some very good and urgently needed products. The NIH and NSF fund a lot of brilliant research, but their hegemony over scientific funding makes it hard to know whether we could be doing much, much better.

American science needs more science. That means, above all, that we need more experiments. We shouldn’t have to depend on 20th-century institutions to guide 21st-century progress. The lesson of Fast Grants is that we don’t have to.

No comments:

Post a Comment