Cows in the Amazon: beef farming is the main cause of deforestation.

UK prime minister Boris Johnson launched the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow with the mantra of “coal, cars, cash and trees”. But thus far the summit has largely ignored the elephant in the room. Or rather, the cows, pigs, chickens and fish.

The global food system is currently responsible for about a quarter of all human made greenhouse gases, a figure that is projected to increase. The increase in food system emissions alone threatens warming above 1.5℃. There is no doubt we need to stop burning fossil fuels, but reducing livestock consumption in high- and middle-income countries is also vital to both protect the climate and restore nature.

Governments at COP26 have pledged to halt deforestation and cut methane emissions 30% by 2030. Eating lots of meat is a big driver of both, but so far no reduction targets have been announced. The pledge to protect nature signed by 45 governments didn’t mention meat consumption at all, while the US agriculture secretary claimed in an interview that Americans don’t need to produce or eat less meat at all.

Here are four reasons why less meat (and dairy) on our plates needs to be on the table at COP26.

1. Livestock have high carbon footprints

It is not very efficient to feed plants to livestock when we could eat the plants directly ourselves. Even though cows, sheep and goats can eat grass, unlike humans, they still need lots of land for grazing which could otherwise store more carbon dioxide as natural forests, grasslands or bogs, or in some cases be used to grow plant crops for human consumption. These animals also produce substantial amounts of methane in their digestive systems, which is a powerful greenhouse gas.

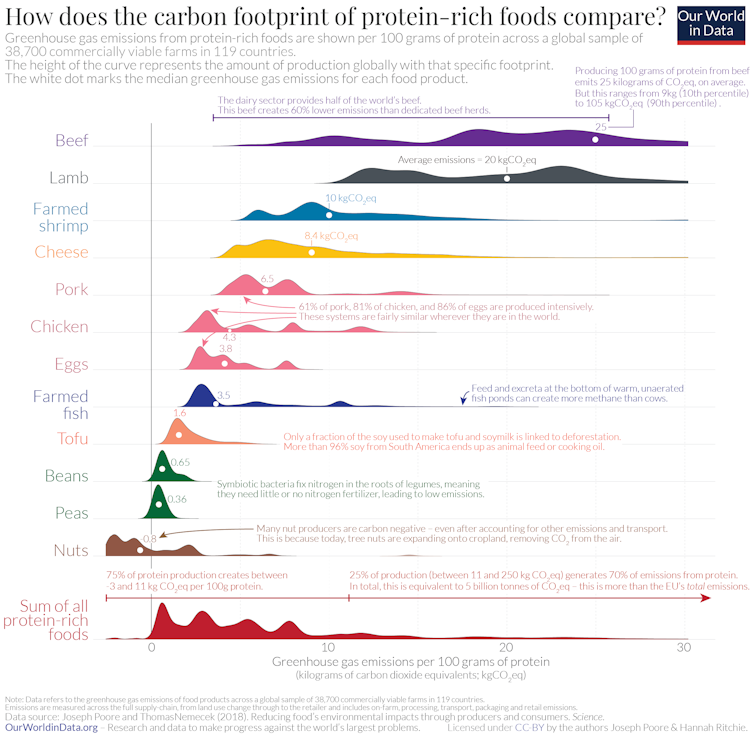

The carbon footprint of beef and lamb is roughly three times higher than that of pork, poultry or farmed fish per 100g of protein, and 24 times higher than pulses such as beans and lentils. Livestock produces just 18% of global calories and 37% of protein, but is responsible for more than half of food’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Small amounts of meat and dairy have a role in sustainable food systems, while some plants have quite high environmental impacts and some nuts use lots of water. But in general, even meat with the lowest carbon footprints still has higher emissions than the highest emitting plant-based foods which are high in protein.

Beef and lamb are by far the most carbon-intensive sources of protein. Some nuts can even be carbon negative, if the nut trees are grown on former croplands.

2. Reducing livestock production would protect nature

Farmland takes up 50% of Earth’s habitable land, and the vast majority of that farmland is used for livestock and their feed. Farming is the leading cause of natural habitat loss, which is the biggest threat to wildlife. Beef production is the top driver of tropical forest loss.

Eating more meat means that more natural habitat needs to be cleared and deforested, and the diets of people in high- and middle-income countries can be key drivers of global deforestation. Conversely, reducing meat consumption would free up land which could be restored to benefit people and wildlife, and store carbon.

3. Meat production has quadrupled since the 1960s

Since 1961, meat production worldwide has quadrupled as meat supply per person has almost doubled (from 23kg to more than 43kg) and the human population has more than doubled (from 3 billion to 7 billion).

The number of animals slaughtered each year has consequently skyrocketed. The number of chickens killed each year has increased tenfold since the 1960s (from 6.6 billion to 68.8 billion), pigs have almost quadrupled (0.4 billion to 1.5 billion) and cows have increased from 0.2 billion to 0.3 billion.

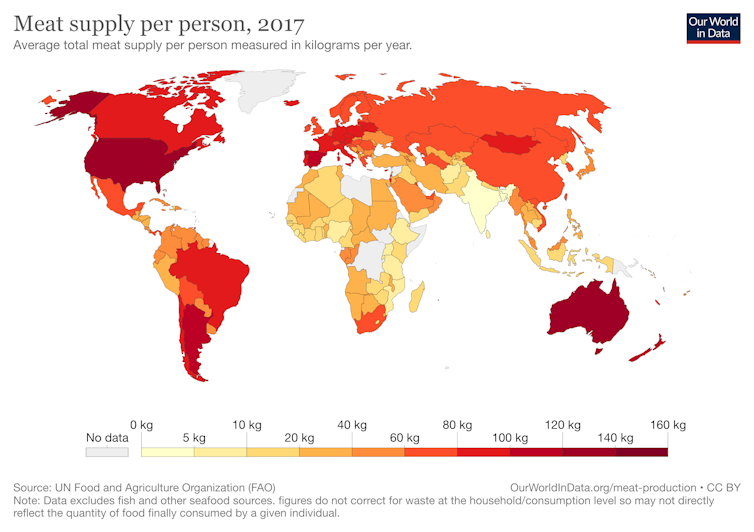

Meat consumption is also very unevenly distributed. Just as richer countries tend to have higher greenhouse gas emissions, they also tend to eat more meat. For example, the average US citizen is supplied with 124kg of meat a year, whereas in China, Nigeria and India it’s 61kg, 7kg and 4kg respectively.

A map of global meat supply looks similar to a map of carbon footprints or average incomes. FAO / Our World in Data, CC BY-SA

4. More sustainable means more healthy

Healthy and sustainable diets broadly overlap: diets with small amounts of red and processed meat, and high in vegetables, wholegrains and pulses. There are some important exceptions: oily fish benefits health but the fuel used by fishing boats means it generally has higher greenhouse gas emissions than plant-based proteins, while many fish populations are overfished. Sugar, on the other hand, has a relatively low environmental impact but doesn’t have any nutritional value besides calories.

The Planetary Health Diet – a healthy diet designed to minimise environmental damage – recommends on average three small portions of meat, two small portions of fish and seven glasses of milk a week. However, many of the poorest people in low-income countries eat less meat and fish than this or don’t have access to healthy alternative foods. They could benefit from increasing, not decreasing, the amount of animal products they eat. This makes it even more vital that people eating lots of meat, fish and dairy cut back.

There are many different policies that could make healthy and sustainable diets more accessible. These include removing subsidies for livestock farming, helping livestock farmers to transition to alternative farming systems, making menus mostly plant-based, and promoting behaviour changes through prominent positioning and cheaper prices for healthy and sustainable food. Education and public information – while important – won’t be enough by themselves. We need to step up to the plate: the planet depends on it.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage on COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. More.

Sustainability Research Fellow, University of Cambridge

Disclosure statement

Emma Garnett would like to thank Gianna Huhn and Amy Munroe-Faure for comments on this piece.

World leaders shy away from tackling food, farming emissions at COP26

'We need to take a close look at ourselves in our own

practices,' says Ontario farmer attending climate talks

When Nick Morrow decided to go vegan eight years ago, he wasn't thinking about climate change.

Instead, he was motivated by the health benefits after his dad had suffered a severe stroke — and as an animal lover, he was also concerned about how livestock were treated.

Since opening the Picnic, a café in Glasgow that is one of the city's most popular vegan restaurants, he's noticed how a plant-based diet has become mainstream, with more choices on store shelves and better labelling on menus and packaging.

While the environment was far from his mind when he decided to ditch meat and dairy, Morrow said it's often the impetus for why people these days make the dietary switch.

And with Glasgow hosting the COP26 climate conference this month, Morrow said he can only shake his head as world leaders discuss many issues related to global warming — but avoid talk of food production or agriculture generally.

"Most people who are vegan are very mindful of the fact that animal agriculture, in regards to CO2 emissions, is pretty much the elephant in the room," said Morrow.

Or as some plant-based advocates describe it — the "cow in the room."

They say a change in our diets can help to solve climate change.

"The scale and speed of the shift that is needed to halt and reverse the climate damage caused by livestock demands world leaders to take decisive action," said Sean Mackenney, with the Humane Society International.

"COP26 has been framed as a Race to Zero. But in its refusal to set ambitious targets and strategies to meaningfully reduce the kinds of impacts of animal agriculture, it is more like a gentle Sunday stroll," he said.

The Conference of Parties (COP) meets every year and is the global decision-making body set up in the 1990s to implement the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and subsequent climate agreements.

Regardless of plant- or animal-based agriculture, the marginalization of the subject at COP26 mirrors how governments around the world are often hesitant to address the sector's climate impacts.

In Canada, farmers are often spared from some parts of the carbon tax, because governments decide to provide exemptions on things like farm fuel and natural gas to heat greenhouses.

When the federal government raised its methane-reduction goal last month, also announcing its support for the Global Methane Pledge, the focus was on emissions from the oilpatch.

For the agriculture industry, there are no regulations or federal targets in place, even though the sector is responsible for 29 per cent of Canada's total methane emissions.

Methane is a natural byproduct of cattle digestion, meaning it is emitted into the atmosphere every time a cow burps or farts. Experts say it's more complicated to tackle methane emissions from agriculture compared to oil and natural gas production.

Agriculture represents about 10 per cent of Canada's overall emissions, a figure which has remained relatively flat over the last few decades. Over that time, there have been fluctuations in the source of those emissions because of trends within the industry; major livestock populations peaked in 2005 before decreasing sharply until 2011, while fertilizer use is up 71 per cent since 2005.

In total, food production counts for about one-third of global emissions, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. At COP26, there are specific days focused on themes, such as energy, finance, transport, youth and cities; agriculture was mixed together with land and ocean management, under the theme of nature.

"I'm not sure … if that means politicians don't know what to do with agriculture and they don't know how to solve the problem, or whether they're afraid to jump into this talk with farmers," said Stuart Oke, a vegetable and flower farmer from Ontario who is in Glasgow representing the National Farmers Union at COP26.

After two significant floods in the last five years in the Ottawa region, Oke said he is concerned about what farming will be like in 20 or 30 years, as climate change causes more severe and frequent natural disasters.

Oke's message is that farmers want to be part of the solution and can make changes to reduce emissions, such as more efficient use of fertilizers. More support for research and technology will help, he said.

Livestock are central to the food system, he said, since even his farm uses animal manure. But he acknowledges that every part of the industry needs to be sustainable.

"We need to take a close look at ourselves in our own practices, and ask ourselves, like everybody should be, 'What can we do to be part of the solution here? And how can we help to adapt and make our firms and food system grow a lot more resilient than it is now?" he said.

WATCH | Why this Ontario farmer made the trip to Scotland for COP26:

Certain farming practices, like zero tillage and the maintenance of grasslands, can act as a carbon sink and absorb some emissions.

But these practices were estimated to have eliminated about four million tonnes of CO2 in 2019, compared to the more than 70 million tonnes generated by the agriculture industry as a whole, including the use of on-farm fuel. The production of ammonia for use in fertilizers increases that level of emissions by an extra two million tonnes, according to federal data.

Ottawa has also committed $200 million to a fund aimed at reducing emissions from agriculture and helping farmers adapt to climate change.

No comments:

Post a Comment