By The Echo

November 29, 2021

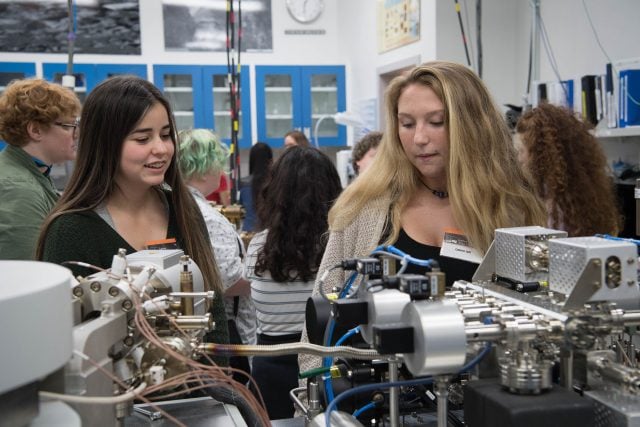

Kate Quigley was a finalist in the Queensland Women In Stem Prize 2020 for her work on helping corals withstand increasing ocean temperatures. Photo https://www.worldsciencefestival.com.au

Brought to you by The Echo and Cosmos Magazine

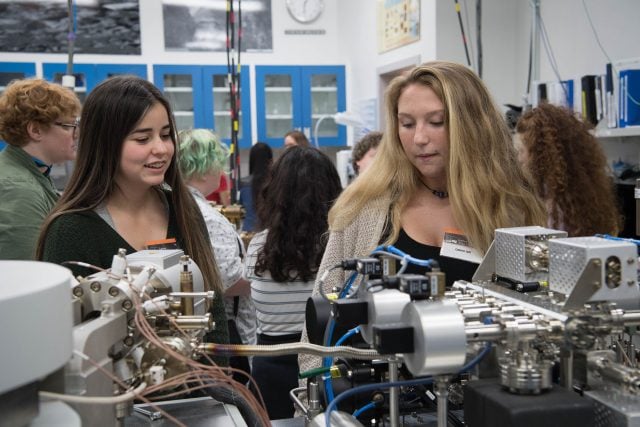

An experiment tests gender stereotyping in computer science.

Even children as young as six can develop ideas that girls don’t like computer science and engineering as much as boys – stereotypes that carry over into teenagerhood and contribute to gender gaps at university, according to a study published in PNAS.

‘Gender-interest stereotypes that STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) is for boys begins in grade school, and by the time they reach high school, many girls have made their decision not to pursue degrees in computer science and engineering because they feel they don’t belong,’ says lead author Allison Master, of the University of Houston.

The study involved four different experiments to assess the beliefs of a racially diverse sample of children and teens right throughout school. Instead of exploring who children perceived as ‘good’ at STEM subjects, they investigated who children thought liked them, which can affect childrens’ sense of belonging and willingness to participate in STEM-related activities.

Brought to you by The Echo and Cosmos Magazine

An experiment tests gender stereotyping in computer science.

Even children as young as six can develop ideas that girls don’t like computer science and engineering as much as boys – stereotypes that carry over into teenagerhood and contribute to gender gaps at university, according to a study published in PNAS.

‘Gender-interest stereotypes that STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) is for boys begins in grade school, and by the time they reach high school, many girls have made their decision not to pursue degrees in computer science and engineering because they feel they don’t belong,’ says lead author Allison Master, of the University of Houston.

The study involved four different experiments to assess the beliefs of a racially diverse sample of children and teens right throughout school. Instead of exploring who children perceived as ‘good’ at STEM subjects, they investigated who children thought liked them, which can affect childrens’ sense of belonging and willingness to participate in STEM-related activities.

Photo NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The researchers found that over half of the children (51 per cent) believed that girls were less interested in computer science than boys, and two-thirds believed girls enjoyed engineering less than boys – even in children as young as six. In comparison, only 14 per cent thought girls liked computer science better than boys did, and nine per cent felt the same about engineering.

Children were then provided with different activities to see whether their beliefs influenced what they chose to participate in.

They found that when girls were told boys liked it better, only 35 per cent of girls participated. On the other hand, when the children were told that boys and girls like computer science just as much as each other, 65 per cent of girls chose to join in.

‘The large surveys told us that the kids had absorbed the cultural stereotype that girls are less interested in computer science and engineering. In the experiments we zeroed in on causal mechanisms and consequences of stereotypes,’ says co-author Andrew Meltzoff, of the University of Washington.

‘We discovered that labelling an activity in a stereotyped way influenced children’s interest in it and their willingness to take it home – the mere presence of the stereotype influenced kids in dramatic ways. This brought home to us the pernicious effect of stereotypes on children and teens.’

Ultimately, this means that many girls chose not to participate in computer science or engineering activities because they felt like they didn’t belong.

‘Current gender disparities in computer science and engineering careers are troubling because these careers are lucrative, high status, and influence so many aspects of our daily lives,’ says co-author Sapna Cheryan of the University of Washington.

‘The dearth of gender and racial diversity in these fields may be one of the reasons why many products and services have had negative consequences for women and people of colour.’

Researchers say the study can be used to understand why a child is motivated to participate in or avoid a class. They also note that parents and teachers can help counteract these stereotypes by supporting and encouraging girls’ interests in STEM subjects from an early age.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Institute of Education Sciences at the U.S. Department of Education, and the Bezos Family Foundation.

This article was originally published on Cosmos Magazine and was written by Deborah Devis. Deborah Devis is a science journalist at Cosmos. She has a Bachelor of Liberal Arts and Science (Honours) in biology and philosophy from the University of Sydney, and a PhD in plant molecular genetics from the University of Adelaide

The researchers found that over half of the children (51 per cent) believed that girls were less interested in computer science than boys, and two-thirds believed girls enjoyed engineering less than boys – even in children as young as six. In comparison, only 14 per cent thought girls liked computer science better than boys did, and nine per cent felt the same about engineering.

Children were then provided with different activities to see whether their beliefs influenced what they chose to participate in.

They found that when girls were told boys liked it better, only 35 per cent of girls participated. On the other hand, when the children were told that boys and girls like computer science just as much as each other, 65 per cent of girls chose to join in.

‘The large surveys told us that the kids had absorbed the cultural stereotype that girls are less interested in computer science and engineering. In the experiments we zeroed in on causal mechanisms and consequences of stereotypes,’ says co-author Andrew Meltzoff, of the University of Washington.

‘We discovered that labelling an activity in a stereotyped way influenced children’s interest in it and their willingness to take it home – the mere presence of the stereotype influenced kids in dramatic ways. This brought home to us the pernicious effect of stereotypes on children and teens.’

Ultimately, this means that many girls chose not to participate in computer science or engineering activities because they felt like they didn’t belong.

‘Current gender disparities in computer science and engineering careers are troubling because these careers are lucrative, high status, and influence so many aspects of our daily lives,’ says co-author Sapna Cheryan of the University of Washington.

‘The dearth of gender and racial diversity in these fields may be one of the reasons why many products and services have had negative consequences for women and people of colour.’

Researchers say the study can be used to understand why a child is motivated to participate in or avoid a class. They also note that parents and teachers can help counteract these stereotypes by supporting and encouraging girls’ interests in STEM subjects from an early age.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Institute of Education Sciences at the U.S. Department of Education, and the Bezos Family Foundation.

This article was originally published on Cosmos Magazine and was written by Deborah Devis. Deborah Devis is a science journalist at Cosmos. She has a Bachelor of Liberal Arts and Science (Honours) in biology and philosophy from the University of Sydney, and a PhD in plant molecular genetics from the University of Adelaide

No comments:

Post a Comment