December 04, 2021

VOA News

Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei joins supporters of Julian Assange as they stage a demonstration outside the High Court in London, Oct. 27, 2021

HONG KONG —

Art censorship in Hong Kong is “very much real,” an expert said after the city’s much-anticipated art gallery opened recently without showcasing some expected artworks by a Chinese dissident.

The former British colony’s largest art museum, M+, opened Nov. 12 to great fanfare, but also heated debate because of its failure to exhibit two of famous exiled artist Ai Wei Wei’s artworks in a donated collection of celebrated Swiss art collector Uli Sigg.

Among the collection of contemporary Chinese art from the 1970s to the 2000s, Ai’s Study of Perspective: Tiananmen, a photo that features Ai’s middle finger in front of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, and Map of China, a sculpture made of salvaged wood from a Qing Dynasty temple, have been under review by authorities since March this year, essentially barring them from display.

That came two weeks after M+ director Suhanya Raffel guaranteed that the gallery would show Ai’s art and pieces about the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, according to The South China Morning Post.

In the same month, Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam said the authorities would be on “full alert” to ensure museum exhibitions would not undermine national security, after pro-Beijing lawmakers said the artworks at M+ caused “great concerns” to the public for “spreading hatred” against China, public broadcaster RTHK reported.

In a September editorial in local media outlet Stand News, Ai called the government’s decision to shelve his two pieces “incredible.”

“The Study of Perspective series I started at Tiananmen Square 26 years ago once again became the testing ground for an important change in history, and a convincing note for China’s political censorship of its culture and art,” Ai wrote. Other images in the series featured the middle finger in front of the White House, the Swiss parliament and the Mona Lisa.

Sigg donated over 1,400 artworks and sold 47 pieces to M+ gallery in 2012, before the city experienced political turmoil from the 2014 Occupy Central movement, the 2019 anti-government protests and implementation of the controversial national security law last year.

HONG KONG —

Art censorship in Hong Kong is “very much real,” an expert said after the city’s much-anticipated art gallery opened recently without showcasing some expected artworks by a Chinese dissident.

The former British colony’s largest art museum, M+, opened Nov. 12 to great fanfare, but also heated debate because of its failure to exhibit two of famous exiled artist Ai Wei Wei’s artworks in a donated collection of celebrated Swiss art collector Uli Sigg.

Among the collection of contemporary Chinese art from the 1970s to the 2000s, Ai’s Study of Perspective: Tiananmen, a photo that features Ai’s middle finger in front of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, and Map of China, a sculpture made of salvaged wood from a Qing Dynasty temple, have been under review by authorities since March this year, essentially barring them from display.

That came two weeks after M+ director Suhanya Raffel guaranteed that the gallery would show Ai’s art and pieces about the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, according to The South China Morning Post.

In the same month, Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam said the authorities would be on “full alert” to ensure museum exhibitions would not undermine national security, after pro-Beijing lawmakers said the artworks at M+ caused “great concerns” to the public for “spreading hatred” against China, public broadcaster RTHK reported.

In a September editorial in local media outlet Stand News, Ai called the government’s decision to shelve his two pieces “incredible.”

“The Study of Perspective series I started at Tiananmen Square 26 years ago once again became the testing ground for an important change in history, and a convincing note for China’s political censorship of its culture and art,” Ai wrote. Other images in the series featured the middle finger in front of the White House, the Swiss parliament and the Mona Lisa.

Sigg donated over 1,400 artworks and sold 47 pieces to M+ gallery in 2012, before the city experienced political turmoil from the 2014 Occupy Central movement, the 2019 anti-government protests and implementation of the controversial national security law last year.

FILE - A woman walks outside the M+ visual culture museum in the West Kowloon Cultural District of Hong Kong, Nov. 11, 2021.

Sigg originally wanted to make mainland China home to his collection, but no art galleries there could ensure that his artworks, including Ai Wei Wei’s, would be displayed without restriction, according to SOAS University of London art history professor Shane McCausland.

“Hong Kong’s legal framework at the time promised that these artworks could be shown…[but] policy on display will have changed dramatically after the national security law came in,” McCausland told VOA.

The head of the West Kowloon Cultural District, Henry Tang, said ahead of the M+ gallery opening that the board would “uphold and encourage freedom of artistic expression and creativity,” but added that the opening of M+ “does not mean artistic expression is above the law.” He also denied that the two artworks put under review meant they were illegal.

However, such an ostensibly normal bureaucratic act from the government is China’s usual form of censorship, McCausland said.

“It’s often unclear even to the initiated, where the boundary lies, as it moves all the time. The laws are framed in vague language: they often appear to be applied arbitrarily and randomly. …The application depends on the [Chinese] leadership from the top, where there is a degree of sensitivity to criticism and intolerance of critiques,” he said.

Sigg originally wanted to make mainland China home to his collection, but no art galleries there could ensure that his artworks, including Ai Wei Wei’s, would be displayed without restriction, according to SOAS University of London art history professor Shane McCausland.

“Hong Kong’s legal framework at the time promised that these artworks could be shown…[but] policy on display will have changed dramatically after the national security law came in,” McCausland told VOA.

The head of the West Kowloon Cultural District, Henry Tang, said ahead of the M+ gallery opening that the board would “uphold and encourage freedom of artistic expression and creativity,” but added that the opening of M+ “does not mean artistic expression is above the law.” He also denied that the two artworks put under review meant they were illegal.

However, such an ostensibly normal bureaucratic act from the government is China’s usual form of censorship, McCausland said.

“It’s often unclear even to the initiated, where the boundary lies, as it moves all the time. The laws are framed in vague language: they often appear to be applied arbitrarily and randomly. …The application depends on the [Chinese] leadership from the top, where there is a degree of sensitivity to criticism and intolerance of critiques,” he said.

FILE - A painting titled 'Rouge 1992' created by Chinese artist Li Shan, is seen during a media preview in the West Kowloon Cultural District of Hong Kong, Nov. 11, 2021.

The city’s freedom of artistic expression has been declining since the national security law took effect last year, according to a local independent performance and dance artist who asked that she only be identified by her initial, “V.”

“This [the ban] did not come as a surprise - some artists’ works that might be considered sensitive are not allowed to display recently after the national security law was out, not to mention M+ is a government venue,” V told VOA.

Self-censorship has become a norm in Hong Kong’s art circles, V added.

“The atmosphere has been rather tense. Some movie screenings had to be canceled. Now we still want to voice out our views, but we start thinking about if we should express in a very edgy way, or if politics is the only way for us to express,” she said.

A new film censorship law came into effect in November that aims to “prevent and suppress acts or activities that may endanger national security.”

The supposedly autonomous region is now on track to mirror mainland China’s propaganda and censorship, McCausland said.

“Essentially Hong Kong is poised to become very similar to the framework within the rest of China, with artists being vigilant and constantly watching the moving sense of what’s OK and becoming attuned to when the likelihood is high of the system kicking in with legal ramifications, such as house detention or other judicial options that are open to the authorities, which they are happy to use to ensure the public discourse of harmony,” he said.

Growing art censorship is expected to intensify the talent drain in Hong Kong, which has witnessed an exodus to Western countries, including Britain and Canada, since the start of the 2019 anti-government protests, the art expert said.

“We know there was an astounding majority in favor of democracy - the views of the people were very clear but now you are hearing and seeing the space for expression has been closed down, and often in a heavy-handed way,” McCausland said.

The University of Hong Kong, one of Hong Kong’s most prestigious educational institutions, has ordered the removal of a sculpture commemorating the student victims of the Tiananmen crackdown since October. The university cited “the latest risk assessment and legal advice” as the reason for the request to take away the iconic statue that has been in place for the last 24 years.

“Being an ‘artivist’ [activist artist] is not easy anymore - I started thinking about the role I should play in this era. … I can’t say for sure I will go, but some of my artist friends left because funding has become more challenging,” V said.

The city’s freedom of artistic expression has been declining since the national security law took effect last year, according to a local independent performance and dance artist who asked that she only be identified by her initial, “V.”

“This [the ban] did not come as a surprise - some artists’ works that might be considered sensitive are not allowed to display recently after the national security law was out, not to mention M+ is a government venue,” V told VOA.

Self-censorship has become a norm in Hong Kong’s art circles, V added.

“The atmosphere has been rather tense. Some movie screenings had to be canceled. Now we still want to voice out our views, but we start thinking about if we should express in a very edgy way, or if politics is the only way for us to express,” she said.

A new film censorship law came into effect in November that aims to “prevent and suppress acts or activities that may endanger national security.”

The supposedly autonomous region is now on track to mirror mainland China’s propaganda and censorship, McCausland said.

“Essentially Hong Kong is poised to become very similar to the framework within the rest of China, with artists being vigilant and constantly watching the moving sense of what’s OK and becoming attuned to when the likelihood is high of the system kicking in with legal ramifications, such as house detention or other judicial options that are open to the authorities, which they are happy to use to ensure the public discourse of harmony,” he said.

Growing art censorship is expected to intensify the talent drain in Hong Kong, which has witnessed an exodus to Western countries, including Britain and Canada, since the start of the 2019 anti-government protests, the art expert said.

“We know there was an astounding majority in favor of democracy - the views of the people were very clear but now you are hearing and seeing the space for expression has been closed down, and often in a heavy-handed way,” McCausland said.

The University of Hong Kong, one of Hong Kong’s most prestigious educational institutions, has ordered the removal of a sculpture commemorating the student victims of the Tiananmen crackdown since October. The university cited “the latest risk assessment and legal advice” as the reason for the request to take away the iconic statue that has been in place for the last 24 years.

“Being an ‘artivist’ [activist artist] is not easy anymore - I started thinking about the role I should play in this era. … I can’t say for sure I will go, but some of my artist friends left because funding has become more challenging,” V said.

‘There is still hope here’ in Hong Kong: Zhang Xiaogang, Chinese contemporary artist, tours M+ museum

Zhang Xiaogang, the first major Chinese art figure to tour M+, admits to being pleasantly surprised by Hong Kong’s new museum and its exhibitions

Chinese artist Zhang Xiaogang (wearing a cap) in conversation with Pi Li, Sigg Senior Curator of M+, on December 2, 2021. The event was held at the M+ Lounge for patrons of Hong Kong’s new museum of visual culture. Photo: Enid Tsui

“The Dark Trilogy: Fear, Meditation, Sorrow” by Zhang Xiaogang on display ahead of a Sotheby’s auction in Hong Kong in 2020. Photo: SCMP/Sam Tsang

M+ opened on November 12 after 14 years of preparations, at a time when the Hong Kong government’s strict implementation of the National Security Law has impinged on many aspects of life in the city, including the cultural realm: people have been arrested for publishing a children’s book about sheep and wolves that was considered seditious, for example, and the film censorship law amended to allow the screening of films to be banned on national security grounds.

The museum’s Sigg Collection of contemporary Chinese art, which includes three pieces by Zhang, has been attacked for promoting anti-Chinese sentiment by pro-Beijing politicians and newspapers controlled by the Chinese government’s liaison office in Hong Kong. However, M+ insists its curatorial independence has not been affected by politics, and works by dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and paintings referencing the Cultural Revolution and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown remain on display.

Speaking to the Post, Zhang stressed that his long-planned move to Hong Kong was mainly prompted by practical considerations rather than freedom of expression.

“New Beijing” by Wang Xingwei, which references the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, on display at M+. Photo: SCMP/Felix Wong

In 2019, Zhang decided to set up a second home and workshop in Hong Kong because Pace Gallery, which represents him, closed its permanent space in Beijing. He has visited the city many times – coming often to attend the annual Art Basel international art fair – but acknowledged that his knowledge of the city remains shallow. (He could not remember where his Ap Lei Chau workshop is located, for example.)

“It is simply too complicated to move my paintings from Beijing to the gallery here,” he said, referring to the city’s tax-free status and easy connections to the rest of world before the pandemic.

Of his work, Zhang said: “My art is independent of politics and only comes from within. I can make anything I like inside my studio in mainland China.” That is true even for his painting One Day in March 2020 (2020), which he completed shortly after the death of Dr Li Wenliang, the whistle-blower in Wuhan who tried to alert people to the spread of Covid-19 but was reprimanded by the police.

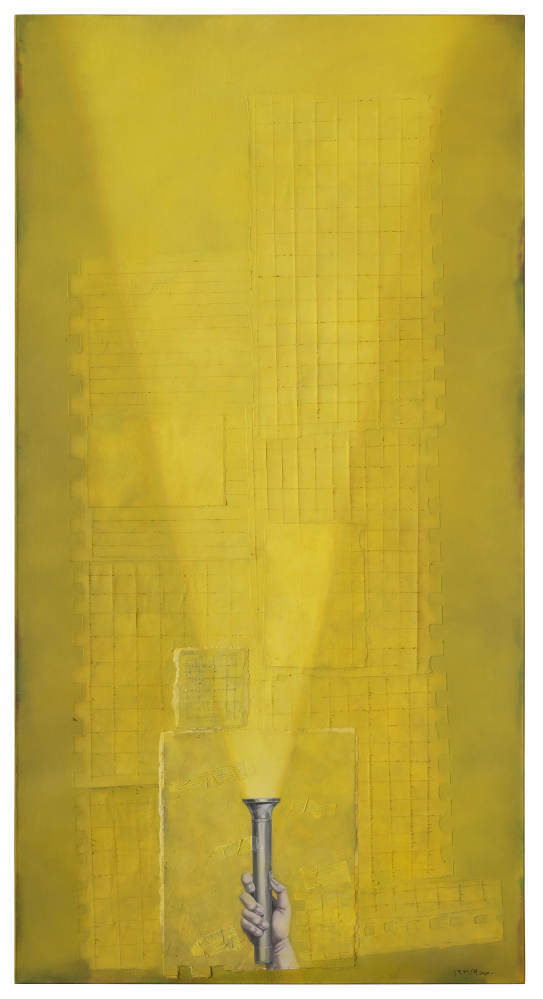

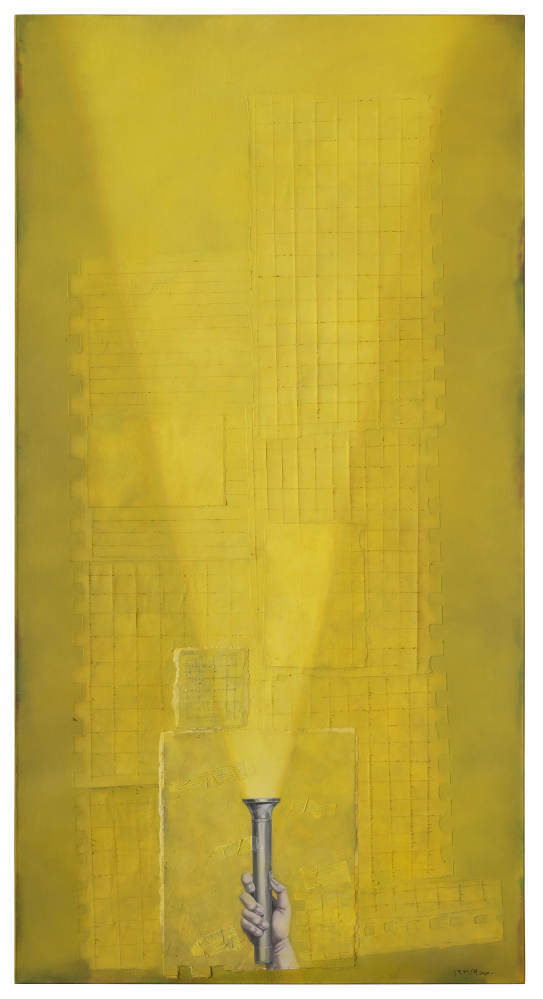

One Day in March 2020, Zhang Xiaogang. Photo: courtesy Pace Gallery

The painting shows a hand holding a torch that illuminates newspaper cuttings about the pandemic. “I have never said it was a commemoration. The painting merely reflects my own emotions. It’s open to interpretation,” Zhang said.

He said he did appreciate the chance to see art in Hong Kong that he wouldn’t see in Beijing, especially as many of the paintings at M+ donated by Swiss collector Uli Sigg were by artists he has known well. “It gives me such a warm feeling to see these works again,” he said.

In a speech at M+, Zhang spoke obliquely about how his whole approach to art changed after the 1989 crackdown on the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement.

Bloodline – Big Family No 3 (1995) by Zhang Xiaogang.

“After 1989, artists like myself experienced a great awakening from within. We felt we had to find our own identity, our own position, role and values in the world. It was a big turning point for me,” he said.

He explained that before 1989, his paintings were “romantic narratives” reflecting on Western art historical materials and philosophy that the 1978 opening up of China had made available to a generation that grew up during the Cultural Revolution. But after a short spell in Germany in 1992, he returned home to look through old family photo albums and saw them with new eyes, he said.

The result was his “Bloodline – Big Family” series. These large oil paintings of Cultural Revolution-era family studio portraits show near-identical faces all bearing the same, expressionless, blank look.

“It moved me that no matter what pain people went through in their lives they looked the same in the photos. I also wanted to reflect certain de-individualised traditions in Chinese aesthetics,” he said.

He has long moved on from this career-making series, and in recent years has produced works that are more surreal and dream-like. Some of these will soon go on display at a new solo exhibition in Shanghai’s Long Museum, he said.

“I look forward to the day when I can have a solo exhibition at M+”, he added.

Zhang Xiaogang, the first major Chinese art figure to tour M+, admits to being pleasantly surprised by Hong Kong’s new museum and its exhibitions

Chinese artist Zhang Xiaogang (wearing a cap) in conversation with Pi Li, Sigg Senior Curator of M+, on December 2, 2021. The event was held at the M+ Lounge for patrons of Hong Kong’s new museum of visual culture. Photo: Enid Tsui

He says it would be ‘difficult’ to show some of its Chinese contemporary art in mainland China, and reaffirms his intention to live and work in Hong Kong

Enid Tsui

Published: 3 Dec, 2021

One of China’s best-known contemporary artists said after touring the newly opened M+ museum it had reassured him there is “still hope” in Hong Kong and that he was ready to live and work in the city as soon as quarantine restrictions on travel are lifted.

Zhang Xiaogang, 63, has painted some of the most recognisable works of the post-1989 generation of Chinese artists, and a large reproduction of his Bloodline – Big Family No. 17 (1998) is displayed prominently in one of the M+ lobbies.

Zhang, who arrived in Hong Kong on November 28, is the first major mainland Chinese artist to see the new museum of visual culture.

Speaking on December 2 to museum patrons, he said he had doubted what M+ could accomplish after the “rich” events of the past two years in Hong Kong, a reference to the 2019 anti-extradition-law protests and subsequent introduction of National Security Law, which includes broad powers of censorship that many fear will diminish the civil liberties enshrined in the city’s mini-constitution.

My art is independent of politics and only comes from within. I can make anything I like inside my studio in mainland ChinaZhang Xiaogang

“The opening hasn’t been very well publicised in mainland China. And the level of anticipation had gone from very strong to numbness over the years. But now that I’m here, I am surprised and also touched to see the building and the exhibitions,” he said.

Without mentioning specific works, he said the contents in the Sigg Galleries of contemporary Chinese art would be “difficult” to show under mainland China’s strict censorship regime. “There is still hope here,” he added.

Enid Tsui

Published: 3 Dec, 2021

One of China’s best-known contemporary artists said after touring the newly opened M+ museum it had reassured him there is “still hope” in Hong Kong and that he was ready to live and work in the city as soon as quarantine restrictions on travel are lifted.

Zhang Xiaogang, 63, has painted some of the most recognisable works of the post-1989 generation of Chinese artists, and a large reproduction of his Bloodline – Big Family No. 17 (1998) is displayed prominently in one of the M+ lobbies.

Zhang, who arrived in Hong Kong on November 28, is the first major mainland Chinese artist to see the new museum of visual culture.

Speaking on December 2 to museum patrons, he said he had doubted what M+ could accomplish after the “rich” events of the past two years in Hong Kong, a reference to the 2019 anti-extradition-law protests and subsequent introduction of National Security Law, which includes broad powers of censorship that many fear will diminish the civil liberties enshrined in the city’s mini-constitution.

My art is independent of politics and only comes from within. I can make anything I like inside my studio in mainland ChinaZhang Xiaogang

“The opening hasn’t been very well publicised in mainland China. And the level of anticipation had gone from very strong to numbness over the years. But now that I’m here, I am surprised and also touched to see the building and the exhibitions,” he said.

Without mentioning specific works, he said the contents in the Sigg Galleries of contemporary Chinese art would be “difficult” to show under mainland China’s strict censorship regime. “There is still hope here,” he added.

“The Dark Trilogy: Fear, Meditation, Sorrow” by Zhang Xiaogang on display ahead of a Sotheby’s auction in Hong Kong in 2020. Photo: SCMP/Sam Tsang

M+ opened on November 12 after 14 years of preparations, at a time when the Hong Kong government’s strict implementation of the National Security Law has impinged on many aspects of life in the city, including the cultural realm: people have been arrested for publishing a children’s book about sheep and wolves that was considered seditious, for example, and the film censorship law amended to allow the screening of films to be banned on national security grounds.

The museum’s Sigg Collection of contemporary Chinese art, which includes three pieces by Zhang, has been attacked for promoting anti-Chinese sentiment by pro-Beijing politicians and newspapers controlled by the Chinese government’s liaison office in Hong Kong. However, M+ insists its curatorial independence has not been affected by politics, and works by dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and paintings referencing the Cultural Revolution and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown remain on display.

Speaking to the Post, Zhang stressed that his long-planned move to Hong Kong was mainly prompted by practical considerations rather than freedom of expression.

“New Beijing” by Wang Xingwei, which references the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, on display at M+. Photo: SCMP/Felix Wong

In 2019, Zhang decided to set up a second home and workshop in Hong Kong because Pace Gallery, which represents him, closed its permanent space in Beijing. He has visited the city many times – coming often to attend the annual Art Basel international art fair – but acknowledged that his knowledge of the city remains shallow. (He could not remember where his Ap Lei Chau workshop is located, for example.)

“It is simply too complicated to move my paintings from Beijing to the gallery here,” he said, referring to the city’s tax-free status and easy connections to the rest of world before the pandemic.

Of his work, Zhang said: “My art is independent of politics and only comes from within. I can make anything I like inside my studio in mainland China.” That is true even for his painting One Day in March 2020 (2020), which he completed shortly after the death of Dr Li Wenliang, the whistle-blower in Wuhan who tried to alert people to the spread of Covid-19 but was reprimanded by the police.

One Day in March 2020, Zhang Xiaogang. Photo: courtesy Pace Gallery

The painting shows a hand holding a torch that illuminates newspaper cuttings about the pandemic. “I have never said it was a commemoration. The painting merely reflects my own emotions. It’s open to interpretation,” Zhang said.

He said he did appreciate the chance to see art in Hong Kong that he wouldn’t see in Beijing, especially as many of the paintings at M+ donated by Swiss collector Uli Sigg were by artists he has known well. “It gives me such a warm feeling to see these works again,” he said.

In a speech at M+, Zhang spoke obliquely about how his whole approach to art changed after the 1989 crackdown on the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement.

Bloodline – Big Family No 3 (1995) by Zhang Xiaogang.

“After 1989, artists like myself experienced a great awakening from within. We felt we had to find our own identity, our own position, role and values in the world. It was a big turning point for me,” he said.

He explained that before 1989, his paintings were “romantic narratives” reflecting on Western art historical materials and philosophy that the 1978 opening up of China had made available to a generation that grew up during the Cultural Revolution. But after a short spell in Germany in 1992, he returned home to look through old family photo albums and saw them with new eyes, he said.

The result was his “Bloodline – Big Family” series. These large oil paintings of Cultural Revolution-era family studio portraits show near-identical faces all bearing the same, expressionless, blank look.

“It moved me that no matter what pain people went through in their lives they looked the same in the photos. I also wanted to reflect certain de-individualised traditions in Chinese aesthetics,” he said.

He has long moved on from this career-making series, and in recent years has produced works that are more surreal and dream-like. Some of these will soon go on display at a new solo exhibition in Shanghai’s Long Museum, he said.

“I look forward to the day when I can have a solo exhibition at M+”, he added.

No comments:

Post a Comment