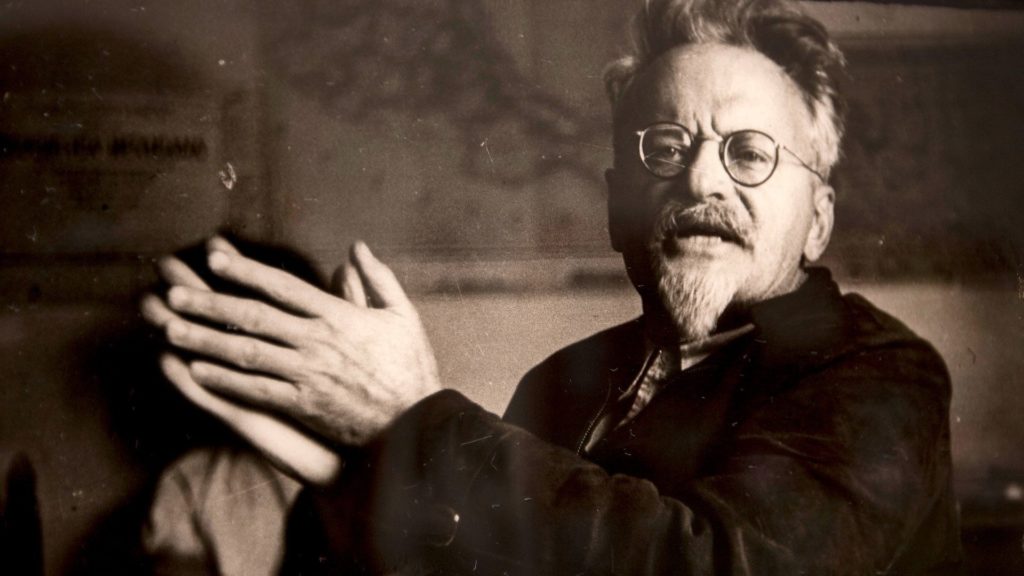

First introduced over a hundred years ago, Leon Trotsky’s theory of Permanent Revolution remains a vital tool for understanding the world today. The theory shows that only the working class can lead a socialist revolution, and is an antidote to many who now claim that we can rely on bourgeois forces to take us half way there.

Kate Frey September 22, 2020

Leon Trotsky’s theory of Permanent Revolution is one of his most important theoretical contributions. It was introduced in Results and Prospects, which was published in 1906, and more fully developed in The Permanent Revolution, published in 1930. Trotsky’s theory drew on his observations of experiences in the Russian revolution of 1905, in which he played a leading role. He also drew on the work of other revolutionary thinkers, including Karl Marx.

Origins of Trotsky’s Theory

Marx believed that the rising Western European business class of the 17th and 18th centuries played a progressive role in sweeping away feudalism and preparing the way for capitalism and democracy. He described how the French Revolution of 1789-93 accomplished a liquidation of feudalism in France, doing away with the absolute monarchy and such norms as internal customs duties, feudal obligations on the peasantry, and an aristocratic state and military system — all of which had fettered the development of the productive forces of society. He also noted that the French Revolution established representative democracy and land reform. All this prepared the way for industrial capitalism’s later development.

By the time of the Revolutions of 1848, much of western Europe had begun to industrialize. A rising bourgeois class was gaining power and an urban working class was growing. Marx observed that in Germany, a country then economically backward, the rising liberal bourgeoisie, in its struggle against the still powerful remnants of the feudal nobility, was unable to fulfill its historic role of unifying and modernizing the country — unlike its earlier French counterpart. Feeling threatened by the growing working class, which did most of the actual fighting in the revolutionary movements, the erstwhile liberal leaders froze in fear and attempted to negotiate with the forces of reaction before their movement collapsed. Similar dynamics played out in other less-developed areas of Europe.

In more developed France, the revolution also failed when bourgeois democrats were unable to advance greater democratic social reforms. This showed that the working class, the class that performed the productive work of society but was also the most oppressed, was the only class capable of advancing society to a higher level of development — by fighting for its own demands. The working class could not depend on the treacherous and vacillating bourgeoisie.

Marx most famously used the term “permanent revolution” in a March 1850 speech; he was referring to a working-class strategy of maintaining political independence with a consistent series of militant political demands and tactics. This prefigured Trotsky’s later theory, which built on Marx’s ideas and asserted that it would be up to the working class to carry forward the struggle against the remnants of feudal despotism and open the way to social advancement in countries where capitalism had developed late, such as Russia.

Unlike Trotsky, Marx did not believe that a society could move directly from control by a semi-feudal aristocracy to the working class being in power. he envisioned a period of rule by the petit bourgeoisie — small shop owners and craftsmen — after the abolition of feudalism. The bourgeoisie, intrinsically opposed to the interests of the working class, would have an interest in preserving and developing capitalist property relations, and in such a situation power would be contested between these two classes. Continued independent working-class struggle would be necessary — a “permanent revolution” until the socialist transformation of society was achieved.

Trotsky drew on these insights to analyze the situation in early 20th-century Russia, which had only abolished serfdom in 1861. Russia was still largely under the control of feudal landlords, who together with the military and church propped up the backward czarist autocracy and impeded the country’s economic development. Russia had begun to industrialize in the late 19th century, with much of the investment for that coming from foreign financiers and the feudal nobility. Because of its history, in which trade was discouraged and during which the country developed as a militarized state on guard against foreign invaders, Russia had a weak independent bourgeois class, and the state took on industrial development This industrialization happened much later than in other Western European countries, and in a top-down fashion. For these reasons, Russia’s bourgeoisie was unable to modernize and develop the country.

In his book 1905, Trotsky explained these class dynamics against the backdrop of Russia’s overseas imperialism, which had led to disaster in the Russo-Japanese War. Trotsky described the vacillating role of the liberal bourgeoisie in the subsequent Revolution of 1905. The Russian bourgeoisie, originally opposed to czarism, quickly abandoned support for the revolution and tried to make an accommodation with the state. It was up to the working class to carry forward the fight against the czarist autocracy, often in bloody street battles. Workers councils, or “soviets,” took control of much of the capital city, Petrograd, for a time. Trotsky himself chaired the short-lived Petrograd Soviet before it was crushed. Unlike how Marx had seen the Revolutions of 1848, Trotsky felt the events of 1905 showed that in Russia, the tasks of national development and democratic reform in Russia, which in more developed countries had been carried out by the bourgeoisie, could be accomplished only by a working-class revolution that would also mobilize the poor peasantry. Trotsky drew on Marx’s insight that the working class would then need to continue its own independent struggle against the bourgeoisie’s attempts to maintain capitalist property relations. In such a situation, the working class would have to carry through to the socialist transformation of society.

Trotsky’s theory was not widely embraced within the socialist movement of his time. Marx had described that many societies progress through increasingly complex levels of organization throughout history. The French Revolution was a milestone in the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Capitalism, in turn, has its own innate contradictions that would be overcome under socialism, when production would be organized and run collectively by working people. Marx’s analysis of history was interpreted by many early 20th-century socialists in a linear and one-dimensional way, with all countries following the same path of development. According to this view — which was held by the Mensheviks, the non-Bolshevik faction in the Russian Marxist movement — Russia could not advance to socialism until capitalism had been fully developed. Since Russia was far from being a fully developed capitalist country, this view led to a political strategy of tailing liberal reformers and subordinating the needs of the working class to that of liberal “allies.” Based on the notion of revolution in “stages,” this approach would be repeated later throughout the world and lead to disastrous consequences for the working class.

Uneven and Combined Development

The theory of Permanent Revolution is closely connected with the law of uneven and combined development. This law was drawn from work by the Latvian theorist Alexander Helphand (Parvus), with whom Trotsky collaborated, as well as the Austrian Marxist Rudolf Hilferding, and was further developed by Trotsky during and after the Russian Revolution.

Trotsky described how societies overall develop at different rates and also that different parts of a society can develop differently; he also explained that by the early 20th century, capitalism had created a global economy that linked productive forces and a world division of labor. Since capitalist development, while happening at different rates in different countries, takes place in this context of a highly globalized and increasingly interdependent economy, sectors of a society can, in effect, “leapfrog” from an underdeveloped status to a highly developed one. This reality is reflected in the theory of Permanent Revolution, as it becomes up to the working class to push society forward.

What was the meaning of this in the Russian context? Russia was then still a backward country, but had nevertheless imported state-of-the-art industrial production. The small Russian working class was very new. Unlike the working class of Britain (for example), it had not gone through a century of reformism and bourgeois democracy; Russian workers were more militant, had fewer illusions about capitalism than their Western counterparts, and were politically far more advanced.

We see the dynamic of uneven and combined development in China today. China has experienced rapid development in recent decades, and a large urban working class, only a generation or so removed from rural peasant backgrounds, has emerged. Foreign and domestic firms have introduced state-of-the-art production throughout the country. Beijing and other cities have ultra-modern subway systems, often the envy of visiting Americans reminded of their own increasingly decrepit infrastructures back home.

Lenin initially believed that because of Russia’s underdevelopment and its weak bourgeois class, completing a bourgeois-democratic revolution, as in France, would be possible only through an alliance of workers and peasants. Although he felt the country would not need to go through an extended period of capitalist development, socialism would not be possible until there were successful workers’ revolutions in western Europe that could aid economically weak Russia. In effect, Russia would have a bourgeois revolution without the bourgeoisie. Lenin put forth the slogan “For a democratic dictatorship of workers and peasants.”

Trotsky disagreed with Lenin’s formulation. He felt the peasant class, which was made up of independent producers, would not be able to unify around common demands and would be politically torn in different directions. He also noted that an agrarian revolution would not be possible in the context of a purely “bourgeois-democratic” revolution. It would be possible only in the context of a transformation of society led by the working class.

The Russian Revolutions of 1917 led Lenin to agree with Trotsky. The October Revolution itself, when a revolutionary movement led by the working class took power, confirmed Trotsky’s theory. After taking power, the Bolsheviks initially did not intend to abolish capitalism altogether immediately. Largely in reaction to economic sabotage by Russian industrialists, workers themselves began seizing factories in a wave of struggle from below, pushing the new Soviet government to begin nationalizing industry much more quickly.

Legacy of the Theory of Permanent Revolution

First proposed more than a century ago, the theory of Permanent Revolution and the related law of uneven and combined development are powerful tools for understanding more recent class dynamics in underdeveloped countries of the global south. After the Chinese revolution of 1949, the Chinese Communist Party initially did not intend to nationalize private industry, and discouraged direct working-class involvement. Economic sabotage by industrialists as well as economic dislocation caused by years of war forced the state to intervene and, in effect, play the role the working class played during the Russian Revolution. More recently, the events of 2011’s Arab Spring — notably in Egypt — showed the importance of an independent working-class movement. After overthrowing Mubarak, a powerful revolutionary movement was derailed by middle-class leaders and led to a military crackdown. Similar dynamics have played out in many other countries.

The law of uneven and combined development — that under capitalism development takes place in the context of a highly globalized world,and that a militant, politically well-developed working class can exist in a society with a more backward, underdeveloped society — reinforces the power of the theory of Permanent Revolution’s argument that it is up to the working class to move society forward. The theory of Permanent Revolution, in turn, provides a powerful argument against reformist “two-stage” theories still popular in the Left and even among liberals who today still assert that the right wing must first be defeated and bourgeois democracy must be installed before an independent workers’ struggle can begin. History and theory have shown that the bourgeoisie’s interests are not those of the working class, and workers rely on the bourgeoisie at their peril.

Ultimately, the working class is the only force that can move society forward to socialism.

No comments:

Post a Comment