FATHER OF SOCIOBIOLOGY

Edward O. Wilson, pioneer in evolutionary biology and Darwin 'heir', dies at 92By Zarrin Ahmed

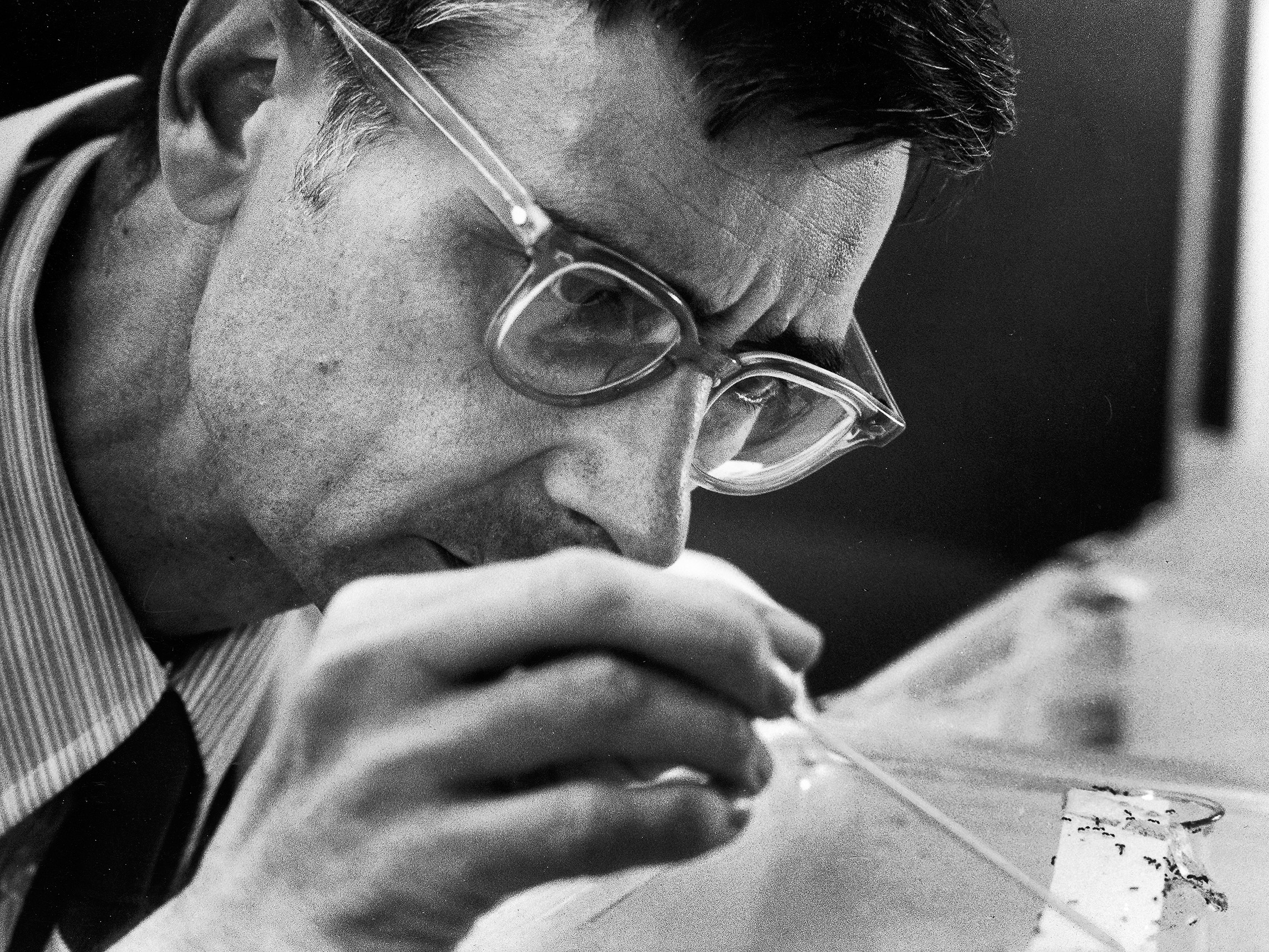

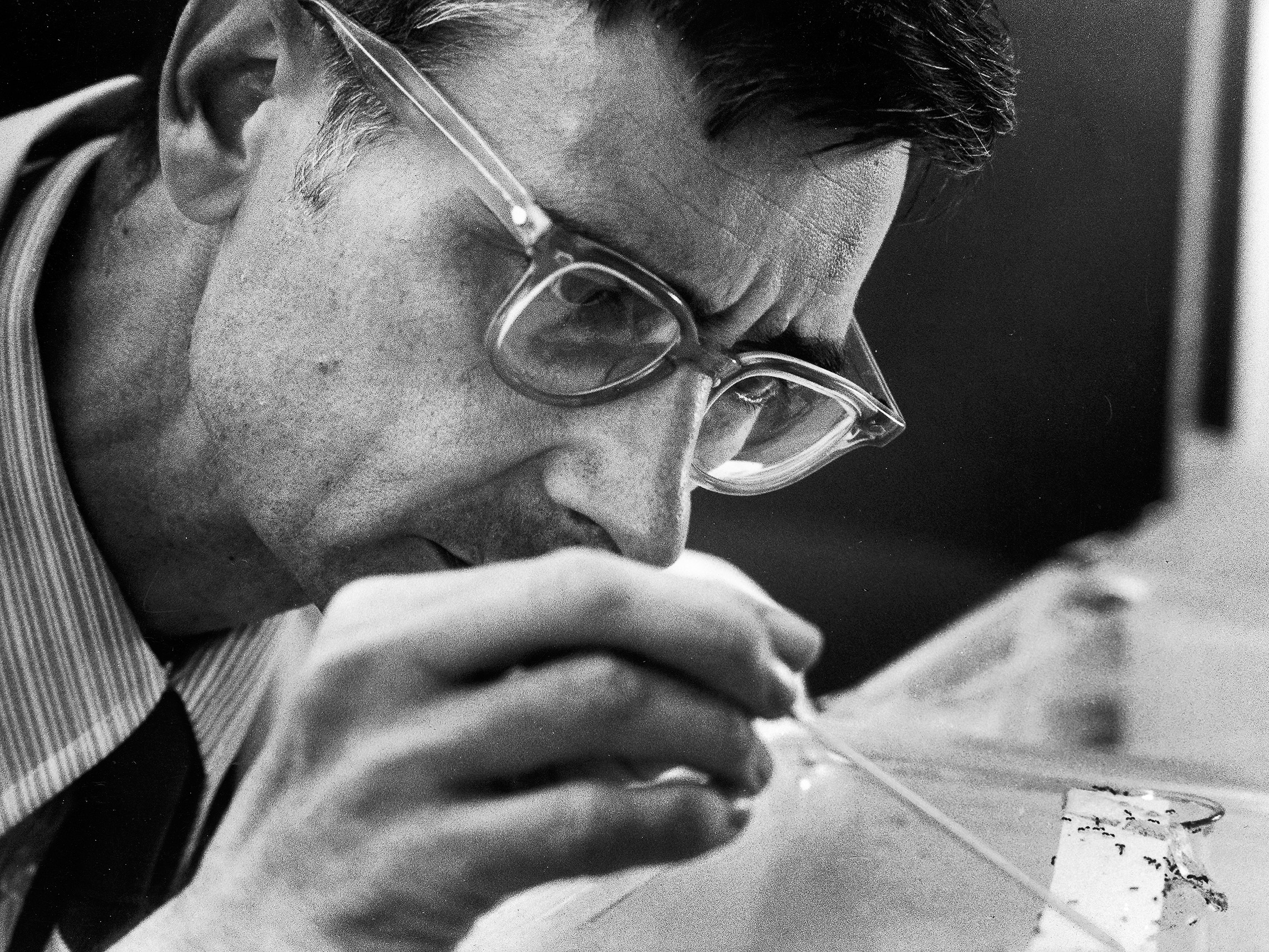

Wilson was a pioneer in evolutionary biology and taught at Harvard for nearly a half-century. He was renowned for studying insects, particularly ants, and examining the influence of natural selection on their behavior. He then applied the research to humans. Photo courtesy E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation

Dec. 27 (UPI) -- Edward O. Wilson, an American naturalist who was often referred to as a modern-day Darwin and professor at Harvard, died at his Massachusetts home on Sunday. He was 92.

Wilson was a pioneer in evolutionary biology and taught at Harvard for nearly a half-century. He was renowned for studying insects, particularly ants, and examining the influence of natural selection on their behavior. He then applied the research to humans.

The E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation reported his death.

"Ed's holy grail was the sheer delight of the pursuit of knowledge. A relentless synthesizer of ideas, his courageous scientific focus and poetic voice transformed our way of understanding ourselves and our planet," foundation president Paula Ehrlich said in a statement.

"His gift was a deep belief in people and our shared human resolve to save the natural world."

An honorary curator in entomology, Wilson also served as chairman of his foundation's board of advisers and chair of the Half-Earth Council.

The two-time Pulitzer Prize-winner wrote more than 30 books and hundreds of scientific papers, and was the creator of two scientific disciplines including sociobiology and advances in global conservation. He also received more than 100 prizes for his work, including the National Medal of Science and Crafoord Prize.

Wilson was referred to as "Darwin's natural heir" and was known as "the ant man" for his work as an entomologist, the foundation said.

"Beloved by his students throughout the world and at Harvard University where he taught, Dr. Wilson was also an adviser to the world's preeminent scientific and conservation organizations," it said in a statement.

"It would be hard to understate Ed's scientific achievements, but his impact extends to every facet of society," David Prend, chairman of the foundation's board, said in a statement.

"He was a true visionary with a unique ability to inspire and galvanize."

Darwin's Natural Heir

I had a bug period like every kid. I just never outgrew mine. I had a kid's natural inclination to explore the environment...Part of the reason was I was an only kid, partly because I could see in only one eye...So, I tended to look very closely at things that were very small.

DATE OF BIRTH June 10, 1929

DATE OF DEATH December 26, 2021

Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama. His father, a government accountant, moved the family frequently, as he was reassigned from Washington, D.C. to Florida, Georgia and Alabama. Lacking steady friends, the young Edward found companionship in nature, exploring Rock Creek Park in Washington, and the wilds of the Deep South. At age seven, while fishing, the fin of a spiny fish scratched his right eye, permanently impairing his distance vision and depth perception. He enjoyed acute near-distance vision with his left eye, and used it to examine insect life at close range. By age 11, he was determined to become an entomologist. When a wartime shortage of pins interrupted his collecting of flies, he turned his attention to ants, which could be stored in jars, and set himself the task of cataloguing every species of ant to be found in Alabama.

A CONVERSATION WITH E.O. WILSON

In 1984, Edward Wilson published a slim volume called Biophilia. In it he proposed the eponymous term, which literally means "love of life," to label what he defined as humans' innate tendency to focus on living things, as opposed to the inanimate. While Wilson acknowledged that hard evidence for the proposition is not yet strong, the scientific study of biophilia being in its infancy, he stressed that "the biophilic tendency is nevertheless so clearly evinced in daily life and widely distributed as to deserve serious attention." He also hoped that an understanding and acceptance of our inherent love of nature, if it exists, might generate a new conservation ethic. On the eve of the book's 25th anniversary, NOVA's Peter Tyson spoke with the "father of biophilia" in his office at Harvard about where the concept stands today and what could happen—to both the natural and human worlds—if we fail to cultivate it.

THE EVIDENCE SO FAR

Q: Is there a general consensus in the scientific community about whether biophilia exists? And if so, about whether it's innate, learned, or a combination of the two?

E.O. Wilson: Well, there is no doubt that I've ever seen that it exists. And there seems to be little doubt, at least I haven't seen a critique of it, that it has at least a partial genetic basis. It's too universal, and the cultural outcomes of it in different parts of the world are too convergent to simply call it an accident of culture. There's probably a complex of propensities that form convergent results in different cultures, but it also produces the ensemble of whatever these propensities are.

We have to distinguish, for example, between the apparently innate preference of habitat—an idea originally worked out by Gordon Orians at the University of Washington—and the deep love people have for their pets, which tends to be more a matter of human surrogates, particularly child surrogates. These are very different impulses, but nonetheless they add up together to something very strong.

And in between, of course, is what can only be broadly called "the love of nature." I think that an attraction for natural environments is so basic that most people will understand it right away. The scientific evidence for the whole ensemble of pieces of it have been summarized in The Biophilia Hypothesis, which Steve Kellert and I edited. That's a little out of date; there's been a lot more since then. But it's a solid body of evidence in different disciplines.

Q: I found that book incredibly rich. You get all these essays from heavy thinkers, people who've really thought about it.

Wilson: That's very true. In fact, there are specialists in aspects of this. For example, those who study the biology and the psychology of phobias quickly arrive at the flip side of biophilia. But I always wanted biophobias to be part of biophilia, because the evidence is that the response to predators and to poisonous snakes (which spreads out to snakes generally) generate so much of our culture: our symbolism, the traits we give gods, the symbols of power, the symbols of fear, and so on. They are so pervasive that we need to include biophobia under the broad umbrella of biophilia, as part of the ensemble that I mentioned.

Q: Since The Biophilia Hypothesis came out in 1993, have there been any genetic discoveries that support the notion of biophilia?

Wilson: I haven't tried to keep up with it beyond that meeting [held in August 1992 at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to discuss biophilia and out of which the book came]. But with work by investigators like Arne Öhman [a psychologist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden who has worked on phobias] and others, they'd already gone into such detail about development and the probable hereditary basis and so on, that the evidence is very strong that way.

Eventually, I think we will know a lot more, including where the genes are located and which fear receptors are activated. I'm pretty sure the fear response will be found to be particularly sensitive to certain inputs, and that will include both pleasurable, emotional feedback and the excitement of fear.

"It's becoming part of the culture to think rationally about saving the natural world."

Q: Do you think, as Gary Paul Nabhan and Sara St. Antoine write in The Biophilia Hypothesis, that the genes for biophilia, if they exist, now have fewer environmental triggers to stimulate their full expression among contemporary cultures than they used to?

Wilson: That's an interesting question. As I pointed out in the chapter on the serpent in Biophilia, the vast majority of people don't ever see a snake in nature. And they're sure not being hunted by cave lions and oversized crocodiles, although they were universally through most of the history of the species. So that part of it is far less true. Also far less true is the chance to unfold more completely a sense of belonging to a habitat, particularly savanna, although that continues to resonate in our making choices for habitation, having city parks, and the like.

So I think that [a sense of biophilia still] resonates strongly, yet probably they are right, it doesn't develop as fully as it did in our ancestors 10,000 or even 5,000 years ago.

AN OPTIMISTIC VIEW

Q: With the world's population exploding, is it still possible for most people to nurture a sense of biophilia? Or is it likely to be just crushed underfoot, particularly among poor people? In the rich countries we have the luxury to think about these things, but what about the peasant farmer in the Amazon who's just trying to feed his family?

Wilson: That is the dilemma of the 21st century—the juggernaut of development, which is extremely hard to stop. The destruction of tropical forests is a good focal point too. (And tropical grassland. Since the 1970s, 80 percent of the tropical grasslands have been destroyed and developed. That's one [ecosystem] we don't think about very much, but tropical grasslands are extremely rich. We don't know how much biodiversity and local ecosystems have gone from that [loss] alone.)

But considering tropical forests, in some parts of the world slash-and-burn [agriculture] has been a key force of destruction. That's particularly true of Africa; that combined with bushmeat hunting is devastating parts of Africa.

We don't need to clear the 4 to 6 percent of the Earth's surface remaining in tropical rain forests, with most of the animal and plant species living there. We don't need to clear that. Any of it. There are ways of taking what's been cleared and devastated, other habitats like saline, you know, with low biodiversity and dry land. The Sahel, the spreading dry country south of the Sahara, begs for the development of dry-land agriculture. Once that gets introduced, even poor people would be better off.

As you can see, I'm a pessimist. No, I'm not a pessimist. [laughs] I'm an optimist.

Q: You are an optimist. But how do you keep optimistic in the face of this juggernaut, as you termed it? And, as you asked in Biophilia, do we humans love the Earth enough to save it?

Wilson: I doubt that most people with short-term thinking love the natural world enough to save it. But more and more are beginning to get a different perspective, particularly in industrialized countries. It's becoming part of the culture to think rationally about saving the natural world. Both because it's the right thing to do—and notice the quick spread of this attitude through the evangelical community—but we will save the natural world in order to save ourselves.

I think the right way of looking at it, and the reason I'm an optimist, is that we still have a lot of elasticity, a lot of wiggle room. The kinds of elasticity and wiggle room that would allow us to save virtually all of the natural environments in the world while dramatically improving ourselves with the land and with the technology yet undeveloped.

Look at this country. This is what I consider real patriotism. Look at the United States of America and say we are at risk from various major movements worldwide of losing our edge, of losing our leadership. We don't need to. We have the greatest scientific minds and capacities in the world. We have experience, and the kind of capitalist system to build technologies swiftly. We can, if we want, lead the world in two areas right away.

One is alternative energy, if we have the will to do it. We can produce the technology that others would beg, borrow, or steal to get. We're in better shape to do it. And we have some elasticity even within our country, so that we're not going to suffer anywhere while we do this changeover.

"Soccer moms are the enemy of natural history and the full development of a child."

The other reason I'm optimistic is what we've been talking about, particularly with reference to the living world. We need a whole new agriculture and silvaculture, the growing of forest, which will take land that has been pretty well ruined as far as natural environments are concerned, and land that's growing dry due to climate change, and develop the crops that can grow in those spreading habitats. The world is going to have to go to dry-land agriculture.

If we can get the crops developed, and find the way—it'll take subsidies at first, you know, prime the pump—to introduce and spread these crops or at least strains of them, replacing the great traditional ones like wheat and potatoes and millet even, we can greatly increase the productivity of [already cleared] lands. I think that's the way we should be thinking, and we should be optimistic about that.

Q: That's refreshing to hear. Getting back to biophilia for a moment….

Wilson: You got me on a soapbox.

Q: No, it's all tied in.

Wilson: I'm happy to tell you, it's getting to be a crowded soapbox. Did you know that Tom Friedman of The New York Times is coming out with a new book this summer? I really like the sound of what he has in mind. He talks like this, but he also is gathering a lot of information to tie together, in something that will appeal to a broad audience, of how we're in an exponential growth phase of so many things: the depletion of resources, the cost of fossil fuels, population, and so on.

All these things are intertwined, and so we have to learn how to look at them as one combined, nonlinear process that's just about going to bear us away unless we handle them now as a whole. I think more and more people are thinking like that. They're deciding that yes, we've really got to face it. And if we do it, there's going to be light at the end of that tunnel. We'll be so much better off.

Q: We'll survive.

Wilson: We'll do more than survive. I think we're going to do very well.

DANGERS OF DISSOCIATION

Q: What could happen to people, to society, if, despite your optimism, we continue to distance ourselves from nature and let our biophilia atrophy?

Wilson: I don't know. There's now a lot of concern, even consternation, among not just naturalists and poets and outdoors professionals but spreading through I think a better part of the educated public, that we've cut ourselves off from something vital to full human psychological and emotional development. I think that the author of Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv, hit on something, because it became such a popular theme to talk about that book [which posits that children today suffer from what Louv calls "nature-deficit disorder"] that people woke up and said, "Yeah, something's wrong."

Just last week I was at the first Aspen Environment Forum in Colorado, and I gave a keynote. I made a remark there: "Soccer moms are the enemy of natural history and the full development of a child." That got applause. [laughs] And many responded afterward agreeing with me. Someone said, "We just over-program kids. We're so desperate to move them in a certain direction that we're leaving out a very important part of childhood." There's a strong feeling that that's the case, that there's something about a child's experience—many of them had it, others have just heard about it—that should be looked at.

I believe that probably a good focus point is biophilia. What is it that we want to cultivate? The dire comparison I make is between children brought up in a totally humanized, artifactual environment, urban or suburban, and cattle brought up in a feedlot. When you see cattle in a feedlot, they seem perfectly content, but they're not cattle. It's an exaggeration, of course, to compare those with children, but somehow children can be perfectly happy with computer screens and games and movies where they get to see not only African wildlife but, lo and behold, dinosaurs. But they're just not fully developing their psychic energy and their propensities to develop and seek on their own.

Q: Could this result in more than stunted psychic development? Could it actually threaten our survival if, because of it, we continue our rampant destruction of nature?

Wilson: It's too hard to call. What does it mean when you say a child or a person hasn't fully developed? Suburban environment, watching football, moving up the ladder at the local corporation, sex, children—all that is pretty satisfying. But what does it mean to have a world that just comes down to that? It's hard to say. All I know is that not developing in that direction, having enough people not having a sense of place associated with nature, is very dangerous to the environment.

At Aspen, each person was allowed three minutes to state one big idea. I gave mine in my keynote. It concerns [what I call] the first rule of climate management. The first rule is that if you save the living environment—save the species and ecosystems that are our cradle and where we developed and on which we've depended for literally millions of years—then automatically you'll save the physical environment. Because you can't save the living environment, of course, without being very careful about the physical environment.

"I'd be willing to place a bet that among people who get out into the outdoors early and really love it, there are fewer depressed people."

But if you save only the physical environment, such as doing what it takes to slow down climate change, get a sustainable source of fresh water, develop alternative fuels, reduce pollution, all the things that people think correctly are of central importance in management of the planet—if that's all you go for, then you will lose them both, the physical and living environments.

Because the living environment is what really sustains us. The living environment creates the soil, creates most of the atmosphere. It's not just something "out there." The biosphere is a membrane, a very thin membrane of living organism. We were born in it, and it presents exactly the right conditions for our lives, including—the whole point of our conversation—psychological and spiritual [benefits].

Q: To what degree do you think that emotional problems that many people today, particularly in cities, suffer from, like depression and anxiety, might be due to a lack of contact with nature?

Wilson: I think it may have a lot to do with it. Psychologists and psychiatrists themselves seem in agreement on the benefits of what's called "the wilderness experience." To be able to [give this to] young people who may have gotten themselves all tangled up with their concerns about ego and peer relationships and their future and are falling into that frame of mind and becoming very depressed because they have such a narrow conception of the world. The wilderness experience is being able to get into a world that's just filled with life, that's fascinating to watch in every aspect, and that does not depend on you. It tells them that there's so much more to the world.

I've never seen a test made of it, but I'd be willing to place a bet that among full-blown outdoorsmen, the birders and the fishermen, people who get out into the outdoors early and really love it, I bet there are fewer depressed people. That's an interesting proposition to check out.

BENEFITS OF BIOPHILIA

Q: I bet you're right. I go out into nature all I can.

Wilson: There are so many things to do. And you know as well as I that it's not just going into a natural environment and saying, "Aah, the air is great, and I love the scenery." Serious naturalists, serious outdoorsmen have goals. They want to see how many birds they can spot. They want to see if they can catch a sight. They're willing to go up, shall we say, the Choctawhatchee River in order to get a glimpse of a swallow-tailed kite. If they're fishermen, they want to fish a certain river to see if they can bring up a large specimen of a certain kind of fish. This is what they live for.

Q: Yes, and they likely identify a lot more closely with those animals and with nature in general than city dwellers. Lately I've been looking at things even as small as ants, your specialty, and thinking, As much evolution went into those creatures as into me. And I've been reading about "immortal genes" that reveal how intimately we're tied to all other creatures on this planet. Why is it so hard for us humans to accept that we are cousin to all other living things?

Wilson: Because we're tribal. It's always been a great survival value for people to believe they belong to a superior tribe. That's just in human relationships. Spirit, patriotism, courage under fire, all these things have been generated almost certainly by group competition, tribe against tribe—an idea, incidentally, first spelled out in some detail by Darwin in Descent of Man. This is where intelligence and courage and altruism and high-quality people come from, he said—the exigencies of tribal conflict. And the tribes that win have what we call the "nobler" qualities in them.

That's an interesting area of theory I'm working in right now. I don't want to go into it, but it's a very hot issue, exactly where altruism and what we call "noble" qualities of humans come from. But it appears to me that much of it occurs from tribal identification and the belief that your tribe is above other tribes. And I think that part of our contempt for the life that supports us is an extension of such tribalism. [pause] How can you love an ant?! [laughs]

Q: How can you love an ant? [laughs too]

Wilson: Well, actually you can. Not love it, but… A couple of years ago I attended a local conference of damselfly specialists and enthusiasts. I thought maybe there'd be five or six coming, people here or there who just happened to like damselflies. My god, there were 30 or 40 of them! And when they all came together, it was the same thing. They all knew the damselflies. One of them from upstate New York had just produced a beautiful guidebook. They gave talks. They told war stories about finding a new bog in Connecticut, you know, which had five species, including two that were endangered. The hunt for Williamsonia, which is a near-extinct one, and how a team was able to locate it in three more ponds on the Cape.

This may be laughable to a person you picked off the street. But these people are talking about animals that are 300 million years old and all that time have been vital parts of the environment. And they're beautiful—most of them are iridescent blue or green. I'll tell you, for me it beats the hell out of NASCAR! [laughs]

Q: And if you asked them if they love their damselflies, I bet they'd say yes.

Wilson: Yes, they would. But they'd want to qualify it, of course. They would say it's a beautiful subject, it's a beautiful world, and it's wonderful to know about something in such detail that when you go out [into the field and find them] it's meaningful.

When I step off a plane anywhere, for example, I'm already looking around, because I know the ants that are supposed to be there. There may be 100 species, but I know them, or many of them, and where they might be found, and so on. It's a familiar world for me, which speaks of the sense of place and a sense of belonging.

"Nature doesn't belong to anybody. And it's not forbidden to touch it. It's his. His!"

Even when the plane is landing and I'm at the window, I start scouring the suburbs. I'm looking at where the housing developments are, where the kids are—you know, like myself when I was 10, 12, 14—and I'm spotting the woodlots that are left and the woods or seemingly natural environments along streams. I'm plotting in my mind—you know, just dreaming—how long it would take to walk or ride a bike from that suburb I see over to that forest. And I'm thinking, I hope the kids there have discovered it. [laughs] I hope they're finding out how to walk it from one end to another and that they're finding tiger salamanders and spotting red-eyed vireos.

Q: Native Americans traditionally had that kind of intimacy with the landscape and its wildlife. What would an Indian hunter of a century or two ago think of what we're doing today, of many people's wanton disregard for the natural world?

Wilson: They never tire of telling us, do they? [laughs] At the opening event in Aspen last week were two Ute Indians, a gentleman and his wife. They had to be very well-educated people, but they put on their traditional dress of the Ute. And he gave us a very fine talk about the Ute tribe, the culture, and so on, which has held on pretty well in the Colorado mountains. And that was the theme: the radical difference in culture, and how we might very well appropriate more of their way of looking at the Earth and not go too far with our way of looking at the Earth.

AT PEACE WITH THE WORLD

Q: I just got a copy of a new book called Biophilic Design, for which you wrote a chapter. So-called biophilic architecture really seems to be taking off.

Wilson: A lot of architects are saying this is the next big thing. Maybe we've had enough around the world of Le Corbusier and buildings and monuments to ourselves. You know, gigantic phalli, huge arches, forbidding terraces and walkways as in our City Hall, neo-Soviet buildings. [laughs] These are things in which we're celebrating our strength, our power, our conquest of the world, right? How great we are! But maybe what we really need down deep is to get closer to where we came from. That doesn't mean we become more primitive, but we just feel better about it.

I recently visited an office building in North Carolina. It was by a professional and very successful architect, and it was [designed biophilically]. He had selected a little knoll. He had to cut some trees, but he left the rest on this little knoll overlooking a stream. And you sit there with a glassed-in wall endlessly looking out, while chipmunks and warblers and so on are all over the place and the stream is flowing by. And you're at peace. I am. [laughs]

Q: I hear you. I have an 11-year-old son who is autistic. He can't go to a mall or fair because they're too overwhelming. Instead I take him out into nature, and he adores it. He calms right down, because there's no competition and there's this natural love for nature, I suppose.

Wilson: I'm pleased to hear that. The thing about nature is it's so rich, and yet it's not owned by other people. I mean, your son sees the remarkable spectacle of a frog springing out and splashing in the water, and a water snake coursing along, and an odd flower growing up—all that doesn't belong to anybody. It's not claimed by somebody over there. And it's not forbidden to touch it. It's his. His!

"The reason I'm an optimist," says Edward Wilson, referring to where society stands in terms of protecting the natural world, "is that we still have a lot of elasticity, a lot of wiggle room." Enough to enable us, he says, "to save virtually all of the natural environments in the world while dramatically improving ourselves with the land and with the technology yet undeveloped."

In Biophilia, Wilson says the human body is well-adapted to life on the African savannas (above, acacias in the Serengeti), then asks, "But is the mind predisposed to life on the savanna, such that beauty in some fashion can be said to lie in the genes of the beholder?" The jury remains out, but strong supporting evidence is accumulating.

Biophobia, the knee-jerk fear we have of venomous snakes and other animals that could harm us—and did over much of our evolutionary history—is the flip side of biophilia, Wilson says. Above, a Southern Pacific rattler.

Dry-land agriculture offers hope for sparing the world's remaining tropical rain forests, Wilson says (above, a portion of the upper Amazon basin in Ecuador). "Once that gets introduced, even poor people would be better off."

The Sahel, the wide strip of dry land that separates the parched Sahara from the moist jungles of Africa's midriff, cries out for dry-land farming, Wilson says. Here, a view of Dogon country in Mali.

"We need a whole new agriculture," Wilson says, one that replaces conventional crops like wheat (above) and thrives in semi-arid environments and already cleared lands.

Children who learn about nature solely from television and computers are not developing fully, Wilson argues. They need to experience wildlife firsthand, like this child holding a snail.

Children who remain out of touch with the natural world are like cattle in a feedlot, Wilson says. They may appear content, but are they children—or cattle—in the fullest sense?

The wilderness experience, which Wilson describes as exploring "a world that's just filled with life, that's fascinating to watch in every aspect," can greatly broaden young people's conception of the world, he says.

A blue damselfly, member of a lineage going back 300 million years. "I'll tell you," Wilson says, referring to these delicate insects and their world, "for me it beats the hell out of NASCAR!"

Scanning the ground for remnant patches of forest, and dreaming about ants going about their lives and kids getting their feet dirty, is par for the course for Ed Wilson whenever he travels by air.

A wild frog, a veritable miracle of evolution, does not belong to anybody, Wilson notes. It and its enormously rich environment are available to any child to observe, study, and enjoy.

Further Reading

Biophilia

by Edward O. Wilson. Harvard University Press, 1984.

The Biophilia Hypothesis

edited by Stephen R. Kellert & Edward O. Wilson. Island Press, 1993.

Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life

edited by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith H. Heerwagen, and Martin L. Mador. Wiley, 2008.

LORD OF THE ANTS

A Conversation With E.O. Wilson

The Boy Naturalist

Man of Ideas

Amazing Ants Game

Watch the Program

Interview conducted in Wilson's office at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology on April 3, 2008 and edited by Peter Tyson, editor in chief of NOVA online

I had a bug period like every kid. I just never outgrew mine. I had a kid's natural inclination to explore the environment...Part of the reason was I was an only kid, partly because I could see in only one eye...So, I tended to look very closely at things that were very small.

DATE OF BIRTH June 10, 1929

DATE OF DEATH December 26, 2021

Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama. His father, a government accountant, moved the family frequently, as he was reassigned from Washington, D.C. to Florida, Georgia and Alabama. Lacking steady friends, the young Edward found companionship in nature, exploring Rock Creek Park in Washington, and the wilds of the Deep South. At age seven, while fishing, the fin of a spiny fish scratched his right eye, permanently impairing his distance vision and depth perception. He enjoyed acute near-distance vision with his left eye, and used it to examine insect life at close range. By age 11, he was determined to become an entomologist. When a wartime shortage of pins interrupted his collecting of flies, he turned his attention to ants, which could be stored in jars, and set himself the task of cataloguing every species of ant to be found in Alabama.

September 8, 1975: American sociobiologist E. O. Wilson studies fire ants in the insectary at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. At age 9, Wilson undertook his first expedition at the Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. He began to collect insects and he gained a passion for butterflies. Going on these expeditions, led to Wilson’s fascination with ants. He describes in his autobiography how “one day he pulled the bark of a rotting tree away and discovered citronella ants underneath. The worker ants he found were short, fat, brilliant, yellow, and emitted a strong lemony odor. Wilson said the event left a vivid and lasting impression on him.” At the age of 18, intent on becoming an entomologist, he began by collecting flies, but the shortage of insect pins caused by World War II caused him to switch to ants, which could be stored in vials. (Hugh Patrick Brown/The LIFE Images Collection)

At age 13, Wilson discovered a colony of non-native fire ants near the docks in Mobile, Alabama and reported his finding to the authorities. By the time he entered the University of Alabama, the fire ant, a potential threat to agriculture, was spreading beyond Mobile, and the State of Alabama requested that Wilson carry out a survey of the ant’s progress. The resulting study, completed in 1949, was his first scientific publication. Wilson received his master’s degree at the University of Alabama in 1950, and after studying briefly at the University of Tennessee, transferred to Harvard for doctoral studies.

Wilson was made a Junior Fellow of Harvard’s Society of Fellows, an appointment that enabled him to pursue field research overseas. He embarked on a number of expeditions in the tropics, exhaustively collecting the ant species of Cuba and Mexico before moving on to the South Pacific. His scientific travels would take him from Australia and New Guinea to Fiji, New Caledonia and Sri Lanka. In 1955, he received his Ph.D. from Harvard and married Irene Kelley. The following year, he joined the Harvard faculty, a relationship that was to last his entire career.

In the first of many contributions to our understanding of species evolution, Wilson tracked the evolution of the hierarchical caste system among ants. Comparing his observations of the ants of the South Pacific with the extensive collection in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, he then devised the theory of the “taxon cycle” to explain how ants adapt to adverse environmental conditions by colonizing new habitats and splitting into new species. The same pattern has since been observed among other insect and bird species. 1983: Dr. Edward O. Wilson joined the faculty of Harvard in 1956. He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on studying their evolution, how they “developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats.” In the 1960s, he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they tested the theory of species equilibrium on a tiny island in the Florida Keys. He eradicated all insect species and observed the re-population by new species. A book The Theory of Island Biogeography about his experiment became a standard ecology text. In 1973, E.O. Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. In 1978, he published On Human Nature which discusses the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize.

1983: Dr. Edward O. Wilson joined the faculty of Harvard in 1956. He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on studying their evolution, how they “developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats.” In the 1960s, he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they tested the theory of species equilibrium on a tiny island in the Florida Keys. He eradicated all insect species and observed the re-population by new species. A book The Theory of Island Biogeography about his experiment became a standard ecology text. In 1973, E.O. Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. In 1978, he published On Human Nature which discusses the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize.

By the end of the 1950s, Wilson had won recognition as the world’s foremost authority on ants, but his studies in taxonomy and ecology ran contrary to prevailing fashion. The discovery of the DNA molecule by James Watson and Francis Crick had focused the biological community’s attention on the molecular basis of life and away from natural history and the study of species evolution. Watson went so far as to compare natural history to stamp collecting. Wilson knew better, and deployed advances in microchemistry to inform the traditional practices of natural history. Collaborating with the mathematician William Bossert, he investigated the phenomenon of chemical communication among ants. Wilson and Bossert identified the chemical compounds, known as pheromones, that permit ants and other species to communicate by sense of smell.

In the 1960s, Edward Wilson enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they attempted to apply the theory of species equilibrium to the contained environment of small islands. The resulting book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, is now a standard work of ecology, and informs conservation policy and the planning of nature reserves around the world. Wilson effectively demonstrated the theory through a remarkable experiment. After eliminating the existing insect population of a tiny island in the Florida Keys, Wilson observed the repopulation of the island by new species, confirming the principles of island biogeographic theory. June 10, 1991: Edward O. Wilson, co-author of The Ants, which won the Pulitzer Prize for general Nonfiction. (AP)

June 10, 1991: Edward O. Wilson, co-author of The Ants, which won the Pulitzer Prize for general Nonfiction. (AP)

Wilson synthesized his enormous body of knowledge on the social insects — ants, bees, wasps and termites — in his masterful work, The Insect Societies, published in 1971. This work invoked the evolving concept of sociobiology, the study of the biological basis of social behavior among different organisms. In 1973, Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Wilson’s work on the sociobiology of insects was well-received, but his next major work ignited a firestorm of controversy.

In Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975), Wilson extended his analysis of animal behavior to vertebrates, including primates, and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that hierarchical social patterns among human beings may be perpetuated by inherited tendencies that originally evolved in response to specific environmental conditions. A number of Wilson’s colleagues took strong exception, and others condemned Wilson’s work on the grounds that it justified sexism, racism, polygamy and a host of other evils. Although Wilson adamantly denied any such intent, demonstrators picketed his lectures, and in one instance protesters doused him with water during a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. On Human Nature, 1978, by E. O. Wilson. Wilson explains how different characteristics of humans and society can be explained from the point of view of evolution.

On Human Nature, 1978, by E. O. Wilson. Wilson explains how different characteristics of humans and society can be explained from the point of view of evolution.

Through the commotion, Wilson stood his ground, and in 1978 published a highly acclaimed work, On Human Nature, in which he thoroughly examined the scientific arguments surrounding the role of biology in the evolution of human culture. Wilson was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction for his graceful and lucid explanation of his ideas. By the end of the decade, the furor over sociobiology had subsided and researchers in many fields now accept Wilson’s ideas as fundamental.

In the decades that followed, Edward Wilson continued to extend the domain of his interests. With collaborator Charles Lumsden, he published Genes, Mind and Culture (1981), introducing the first general theory of gene-culture co-evolution. He followed this with the intriguing Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of Mind (1980). Wilson explored the bond between man and nature in Biophilia, a title that introduced yet another new term to the language of science. Wilson revisited his first scholarly love in The Ants (1990), co-written with Bert Hölldobler, a monumental work that brought Wilson his second Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction.

Over the years, Wilson has been an active participant in the international conservation movement, as a consultant to Columbia University’s Earth Institute, and as a director of the American Museum of Natural History, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund. In the 1990s, he continued to write and publish at a tremendous rate. His published works in this decade included The Diversity of Life (1992) and a memorable autobiography, Naturalist (1994). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) outlined his view of the essential unity of the natural and social sciences

At age 13, Wilson discovered a colony of non-native fire ants near the docks in Mobile, Alabama and reported his finding to the authorities. By the time he entered the University of Alabama, the fire ant, a potential threat to agriculture, was spreading beyond Mobile, and the State of Alabama requested that Wilson carry out a survey of the ant’s progress. The resulting study, completed in 1949, was his first scientific publication. Wilson received his master’s degree at the University of Alabama in 1950, and after studying briefly at the University of Tennessee, transferred to Harvard for doctoral studies.

Wilson was made a Junior Fellow of Harvard’s Society of Fellows, an appointment that enabled him to pursue field research overseas. He embarked on a number of expeditions in the tropics, exhaustively collecting the ant species of Cuba and Mexico before moving on to the South Pacific. His scientific travels would take him from Australia and New Guinea to Fiji, New Caledonia and Sri Lanka. In 1955, he received his Ph.D. from Harvard and married Irene Kelley. The following year, he joined the Harvard faculty, a relationship that was to last his entire career.

In the first of many contributions to our understanding of species evolution, Wilson tracked the evolution of the hierarchical caste system among ants. Comparing his observations of the ants of the South Pacific with the extensive collection in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, he then devised the theory of the “taxon cycle” to explain how ants adapt to adverse environmental conditions by colonizing new habitats and splitting into new species. The same pattern has since been observed among other insect and bird species.

1983: Dr. Edward O. Wilson joined the faculty of Harvard in 1956. He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on studying their evolution, how they “developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats.” In the 1960s, he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they tested the theory of species equilibrium on a tiny island in the Florida Keys. He eradicated all insect species and observed the re-population by new species. A book The Theory of Island Biogeography about his experiment became a standard ecology text. In 1973, E.O. Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. In 1978, he published On Human Nature which discusses the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize.

1983: Dr. Edward O. Wilson joined the faculty of Harvard in 1956. He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on studying their evolution, how they “developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats.” In the 1960s, he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they tested the theory of species equilibrium on a tiny island in the Florida Keys. He eradicated all insect species and observed the re-population by new species. A book The Theory of Island Biogeography about his experiment became a standard ecology text. In 1973, E.O. Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. In 1978, he published On Human Nature which discusses the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize.By the end of the 1950s, Wilson had won recognition as the world’s foremost authority on ants, but his studies in taxonomy and ecology ran contrary to prevailing fashion. The discovery of the DNA molecule by James Watson and Francis Crick had focused the biological community’s attention on the molecular basis of life and away from natural history and the study of species evolution. Watson went so far as to compare natural history to stamp collecting. Wilson knew better, and deployed advances in microchemistry to inform the traditional practices of natural history. Collaborating with the mathematician William Bossert, he investigated the phenomenon of chemical communication among ants. Wilson and Bossert identified the chemical compounds, known as pheromones, that permit ants and other species to communicate by sense of smell.

In the 1960s, Edward Wilson enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Together, they attempted to apply the theory of species equilibrium to the contained environment of small islands. The resulting book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, is now a standard work of ecology, and informs conservation policy and the planning of nature reserves around the world. Wilson effectively demonstrated the theory through a remarkable experiment. After eliminating the existing insect population of a tiny island in the Florida Keys, Wilson observed the repopulation of the island by new species, confirming the principles of island biogeographic theory.

June 10, 1991: Edward O. Wilson, co-author of The Ants, which won the Pulitzer Prize for general Nonfiction. (AP)

June 10, 1991: Edward O. Wilson, co-author of The Ants, which won the Pulitzer Prize for general Nonfiction. (AP)Wilson synthesized his enormous body of knowledge on the social insects — ants, bees, wasps and termites — in his masterful work, The Insect Societies, published in 1971. This work invoked the evolving concept of sociobiology, the study of the biological basis of social behavior among different organisms. In 1973, Wilson was appointed Curator of Insects at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Wilson’s work on the sociobiology of insects was well-received, but his next major work ignited a firestorm of controversy.

In Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975), Wilson extended his analysis of animal behavior to vertebrates, including primates, and in the last chapter, humans. Wilson speculated that hierarchical social patterns among human beings may be perpetuated by inherited tendencies that originally evolved in response to specific environmental conditions. A number of Wilson’s colleagues took strong exception, and others condemned Wilson’s work on the grounds that it justified sexism, racism, polygamy and a host of other evils. Although Wilson adamantly denied any such intent, demonstrators picketed his lectures, and in one instance protesters doused him with water during a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

On Human Nature, 1978, by E. O. Wilson. Wilson explains how different characteristics of humans and society can be explained from the point of view of evolution.

On Human Nature, 1978, by E. O. Wilson. Wilson explains how different characteristics of humans and society can be explained from the point of view of evolution.Through the commotion, Wilson stood his ground, and in 1978 published a highly acclaimed work, On Human Nature, in which he thoroughly examined the scientific arguments surrounding the role of biology in the evolution of human culture. Wilson was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction for his graceful and lucid explanation of his ideas. By the end of the decade, the furor over sociobiology had subsided and researchers in many fields now accept Wilson’s ideas as fundamental.

In the decades that followed, Edward Wilson continued to extend the domain of his interests. With collaborator Charles Lumsden, he published Genes, Mind and Culture (1981), introducing the first general theory of gene-culture co-evolution. He followed this with the intriguing Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of Mind (1980). Wilson explored the bond between man and nature in Biophilia, a title that introduced yet another new term to the language of science. Wilson revisited his first scholarly love in The Ants (1990), co-written with Bert Hölldobler, a monumental work that brought Wilson his second Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction.

Over the years, Wilson has been an active participant in the international conservation movement, as a consultant to Columbia University’s Earth Institute, and as a director of the American Museum of Natural History, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund. In the 1990s, he continued to write and publish at a tremendous rate. His published works in this decade included The Diversity of Life (1992) and a memorable autobiography, Naturalist (1994). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) outlined his view of the essential unity of the natural and social sciences

.

September 2015: Dr. Edward O. Wilson sitting in front of an ant hill. In 1996, Wilson officially retired from Harvard University where he continues to hold the position of Professor Emeritus. He has published 14 books during the new millennium, including, The Future of Life (2002), The Super Organism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies (2009), Anthill: A Novel (2010), Kingdom of Ants (2010), and The Social Conquest of Earth (2012).

Edward Wilson officially retired from teaching at Harvard in 1996. He continues to hold the posts of Professor Emeritus and Honorary Curator in Entomology. Since retiring from teaching, Wilson has continued to write prolifically. His later books include Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth; and Nature Revealed: Selected Writings, 1949-2006. In 2013, he published Letters to a Young Scientist, a memoir in the form of 21 letters, in which he distills 60 years of teaching and a lifetime of experience. He and his wife Irene still make their home in Lexington, Massachusetts.

Edward Wilson officially retired from teaching at Harvard in 1996. He continues to hold the posts of Professor Emeritus and Honorary Curator in Entomology. Since retiring from teaching, Wilson has continued to write prolifically. His later books include Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth; and Nature Revealed: Selected Writings, 1949-2006. In 2013, he published Letters to a Young Scientist, a memoir in the form of 21 letters, in which he distills 60 years of teaching and a lifetime of experience. He and his wife Irene still make their home in Lexington, Massachusetts.

Biologist Edward O. Wilson—The Bard of Biodiversity

"Go to the ant, thou sluggard: consider her ways, and be wise," says the Bible's book of Proverbs. It's advice that biologist Edward O. Wilson of Harvard has taken to heart since boyhood, when he grew fascinated by the complex social behavior of these insects. His 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis sparked fierce controversy after he suggested that human behavior is shaped by the same evolutionary forces that guide the actions of ants and other animals. Wilson's latest project, outlined in The Future of Life (to be published in January 2002 by Alfred A. Knopf) is a blueprint to protecting the world's wildlife and wild lands. He discussed this campaign and other causes close to his heart with Discover associate editor Josie Glausiusz.

Why have you devoted so much of your life to the study of insects? Worldwide, insects are responsible for most of the pollination and are vital for global circulation of materials and energy through all of the land environments, and even parts of the shallow seas. Ants, for example, are the chief predators of other insects, the principal scavengers of small dead animals, and important pollinators and protectors of plants, and they turn more soil worldwide than earthworms.

What would the earth look like without insects? If all insects were to disappear (there are, according to one estimate, about one million trillion alive at any moment) the land ecosystems would collapse. Decomposition of vegetation would slow dramatically, and detritus would pile up to abnormal heights. Pollination of a large percentage of plant species would cease and with it, reproduction. The vast array of other organisms that depend on insects for food, from tiny bacteria and fungi to birds and other vertebrates, would go extinct. Forests would largely if not entirely disappear. And the remaining vegetation would regress to a far simpler, impoverished condition. If humans were to disappear, the land ecosystems would return in a few centuries to near their original healthy, balanced condition.

Why do you fight to protect biodiversity? Almost all current biodiversity analysts agree that the extinction of species is proceeding at one hundred to 10,000 times the pre-human rate, while the rate of origin of new species is decreasing. If more serious conservation measures aren't taken, especially in countries with rainforests and coral reefs, we could lose half the species of plants and animals by the end of the century.

How did we fall into such a morass? Try HIPPO: habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, over-population, and over-harvesting of wild species. Humanity didn't mean for it to turn out this way; we just blundered into the crisis by a multitude of small, largely unconscious actions. These include hunting as many animals as could be caught, clearing as much land as could be converted into agricultural fields, drawing down as much water as could be reached, and other survival practices that on a short-term basis have always seemed perfectly logical.

What's the best way to protect biodiversity? More and larger reserves are the answer, carefully selected by location and biological content and maintained thereafter in such a way as to attract subsidies and other non-invasive sources of income. These include eco-tourism, non-invasive harvesting of medicinals and other wild products, and carefully selective and minimally invasive logging. Above all, we need to ensure that the local governments and people affected would benefit more by conservation than by destructive exploitation.

How have the recent terrorist attacks affected this effort? I've been deeply depressed. Just when we were getting to the point where the environment was becoming an important political issue, suddenly our country is almost completely diverted. That's not good for the environment. Of course, we have to take action. We can't sit here until they drop a nuclear weapon on us. But I hope we keep our eye on the ball.

You've come out publicly in support of genetically modified crops. Why? There are genuine risks associated with transgenic crops. One concern is that you can produce super-weeds and super-bugs, and that the plants or bugs may then get out and take over our world. That's a science-fiction scenario which is worth thinking about, like a giant asteroid striking earth, but it's a remote possibility. There are virtually no cases of any modified strain that could go back and out-compete the natural strain in the original environment. On the other side, the world needs a new, "evergreen" revolution to increase food production while reducing environmental damage.

How has your book, Sociobiology, weathered the winds of time?

Animal sociobiology was always fully accepted, and it helped to revolutionize the study of animal behavior. Human sociobiology, the cause of the ruckus, is now generally accepted. As a fuller picture from human behavioral genetics and neuroscience has emerged, the connections between genes, mind, and culture have become clearer. We have begun to untangle the very complex relation between heredity and environment. We still have a long way to go, however.

You have postulated that religion may have evolved by natural selection. How might that have happened? In general, religion and religion-like faith seem to be a basic part of human nature. Religion has features that enhance survival and reproduction, including the stronger bonding together of tribal groups, and a conquest of the dread of mortality, which is the curse of conscious intelligence. Further, religion appears to have played a very important role in organizing information about the world in mythic form before science undertook more naturalistic explanations.

How then do you explain the modern rise of secularism? The fact is that secularists tend towards the same tribal behavior as religionists. We saw with amazement how the Soviets quickly built up a whole paraphernalia of religion: their icons, preserved in Red Square, their ceremonies, their sacred literature, their prophets. And members of the American Humanist Association, with which I've been affiliated with the for some time, show the same bonding, zeal in their beliefs, and stress upon a hopeful optimistic view of the future as traditional religions do. They're just not as good at it.

Are you yourself religious? I am religious by nature but find my inner peace from commitment to the conservation and celebration of Earth's fauna and flora—including Homo sapiens. While I respect the metaphysical views of others, I see little evidence of God in the horrors and beauty of the world as we now understand them. Nor do I worry about an afterlife.

Both secularism and fundamentalism seem to be thriving. Which way to do you see religion evolving? I think that the belief systems of traditional religions will continue to evolve to a more and more secular state. That's because religions must square with the most solid advances of science, those that contradict old dogma. And they have continuously done so, since the Enlightenment. That is the way science and religion are most likely to be reconciled.

If you could travel back in time, what would you change about this planet? If I could go way back, I'd have humanity reach at least its current level of self-understanding and appreciation of the environment before our species moved out of Africa. How great it would be to explore and embrace the untrammeled living world without destroying it.

"Go to the ant, thou sluggard: consider her ways, and be wise," says the Bible's book of Proverbs. It's advice that biologist Edward O. Wilson of Harvard has taken to heart since boyhood, when he grew fascinated by the complex social behavior of these insects. His 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis sparked fierce controversy after he suggested that human behavior is shaped by the same evolutionary forces that guide the actions of ants and other animals. Wilson's latest project, outlined in The Future of Life (to be published in January 2002 by Alfred A. Knopf) is a blueprint to protecting the world's wildlife and wild lands. He discussed this campaign and other causes close to his heart with Discover associate editor Josie Glausiusz.

Why have you devoted so much of your life to the study of insects? Worldwide, insects are responsible for most of the pollination and are vital for global circulation of materials and energy through all of the land environments, and even parts of the shallow seas. Ants, for example, are the chief predators of other insects, the principal scavengers of small dead animals, and important pollinators and protectors of plants, and they turn more soil worldwide than earthworms.

What would the earth look like without insects? If all insects were to disappear (there are, according to one estimate, about one million trillion alive at any moment) the land ecosystems would collapse. Decomposition of vegetation would slow dramatically, and detritus would pile up to abnormal heights. Pollination of a large percentage of plant species would cease and with it, reproduction. The vast array of other organisms that depend on insects for food, from tiny bacteria and fungi to birds and other vertebrates, would go extinct. Forests would largely if not entirely disappear. And the remaining vegetation would regress to a far simpler, impoverished condition. If humans were to disappear, the land ecosystems would return in a few centuries to near their original healthy, balanced condition.

Why do you fight to protect biodiversity? Almost all current biodiversity analysts agree that the extinction of species is proceeding at one hundred to 10,000 times the pre-human rate, while the rate of origin of new species is decreasing. If more serious conservation measures aren't taken, especially in countries with rainforests and coral reefs, we could lose half the species of plants and animals by the end of the century.

How did we fall into such a morass? Try HIPPO: habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, over-population, and over-harvesting of wild species. Humanity didn't mean for it to turn out this way; we just blundered into the crisis by a multitude of small, largely unconscious actions. These include hunting as many animals as could be caught, clearing as much land as could be converted into agricultural fields, drawing down as much water as could be reached, and other survival practices that on a short-term basis have always seemed perfectly logical.

What's the best way to protect biodiversity? More and larger reserves are the answer, carefully selected by location and biological content and maintained thereafter in such a way as to attract subsidies and other non-invasive sources of income. These include eco-tourism, non-invasive harvesting of medicinals and other wild products, and carefully selective and minimally invasive logging. Above all, we need to ensure that the local governments and people affected would benefit more by conservation than by destructive exploitation.

How have the recent terrorist attacks affected this effort? I've been deeply depressed. Just when we were getting to the point where the environment was becoming an important political issue, suddenly our country is almost completely diverted. That's not good for the environment. Of course, we have to take action. We can't sit here until they drop a nuclear weapon on us. But I hope we keep our eye on the ball.

You've come out publicly in support of genetically modified crops. Why? There are genuine risks associated with transgenic crops. One concern is that you can produce super-weeds and super-bugs, and that the plants or bugs may then get out and take over our world. That's a science-fiction scenario which is worth thinking about, like a giant asteroid striking earth, but it's a remote possibility. There are virtually no cases of any modified strain that could go back and out-compete the natural strain in the original environment. On the other side, the world needs a new, "evergreen" revolution to increase food production while reducing environmental damage.

How has your book, Sociobiology, weathered the winds of time?

Animal sociobiology was always fully accepted, and it helped to revolutionize the study of animal behavior. Human sociobiology, the cause of the ruckus, is now generally accepted. As a fuller picture from human behavioral genetics and neuroscience has emerged, the connections between genes, mind, and culture have become clearer. We have begun to untangle the very complex relation between heredity and environment. We still have a long way to go, however.

You have postulated that religion may have evolved by natural selection. How might that have happened? In general, religion and religion-like faith seem to be a basic part of human nature. Religion has features that enhance survival and reproduction, including the stronger bonding together of tribal groups, and a conquest of the dread of mortality, which is the curse of conscious intelligence. Further, religion appears to have played a very important role in organizing information about the world in mythic form before science undertook more naturalistic explanations.

How then do you explain the modern rise of secularism? The fact is that secularists tend towards the same tribal behavior as religionists. We saw with amazement how the Soviets quickly built up a whole paraphernalia of religion: their icons, preserved in Red Square, their ceremonies, their sacred literature, their prophets. And members of the American Humanist Association, with which I've been affiliated with the for some time, show the same bonding, zeal in their beliefs, and stress upon a hopeful optimistic view of the future as traditional religions do. They're just not as good at it.

Are you yourself religious? I am religious by nature but find my inner peace from commitment to the conservation and celebration of Earth's fauna and flora—including Homo sapiens. While I respect the metaphysical views of others, I see little evidence of God in the horrors and beauty of the world as we now understand them. Nor do I worry about an afterlife.

Both secularism and fundamentalism seem to be thriving. Which way to do you see religion evolving? I think that the belief systems of traditional religions will continue to evolve to a more and more secular state. That's because religions must square with the most solid advances of science, those that contradict old dogma. And they have continuously done so, since the Enlightenment. That is the way science and religion are most likely to be reconciled.

If you could travel back in time, what would you change about this planet? If I could go way back, I'd have humanity reach at least its current level of self-understanding and appreciation of the environment before our species moved out of Africa. How great it would be to explore and embrace the untrammeled living world without destroying it.

A CONVERSATION WITH E.O. WILSON

In 1984, Edward Wilson published a slim volume called Biophilia. In it he proposed the eponymous term, which literally means "love of life," to label what he defined as humans' innate tendency to focus on living things, as opposed to the inanimate. While Wilson acknowledged that hard evidence for the proposition is not yet strong, the scientific study of biophilia being in its infancy, he stressed that "the biophilic tendency is nevertheless so clearly evinced in daily life and widely distributed as to deserve serious attention." He also hoped that an understanding and acceptance of our inherent love of nature, if it exists, might generate a new conservation ethic. On the eve of the book's 25th anniversary, NOVA's Peter Tyson spoke with the "father of biophilia" in his office at Harvard about where the concept stands today and what could happen—to both the natural and human worlds—if we fail to cultivate it.

THE EVIDENCE SO FAR

Q: Is there a general consensus in the scientific community about whether biophilia exists? And if so, about whether it's innate, learned, or a combination of the two?

E.O. Wilson: Well, there is no doubt that I've ever seen that it exists. And there seems to be little doubt, at least I haven't seen a critique of it, that it has at least a partial genetic basis. It's too universal, and the cultural outcomes of it in different parts of the world are too convergent to simply call it an accident of culture. There's probably a complex of propensities that form convergent results in different cultures, but it also produces the ensemble of whatever these propensities are.

We have to distinguish, for example, between the apparently innate preference of habitat—an idea originally worked out by Gordon Orians at the University of Washington—and the deep love people have for their pets, which tends to be more a matter of human surrogates, particularly child surrogates. These are very different impulses, but nonetheless they add up together to something very strong.

And in between, of course, is what can only be broadly called "the love of nature." I think that an attraction for natural environments is so basic that most people will understand it right away. The scientific evidence for the whole ensemble of pieces of it have been summarized in The Biophilia Hypothesis, which Steve Kellert and I edited. That's a little out of date; there's been a lot more since then. But it's a solid body of evidence in different disciplines.

Q: I found that book incredibly rich. You get all these essays from heavy thinkers, people who've really thought about it.

Wilson: That's very true. In fact, there are specialists in aspects of this. For example, those who study the biology and the psychology of phobias quickly arrive at the flip side of biophilia. But I always wanted biophobias to be part of biophilia, because the evidence is that the response to predators and to poisonous snakes (which spreads out to snakes generally) generate so much of our culture: our symbolism, the traits we give gods, the symbols of power, the symbols of fear, and so on. They are so pervasive that we need to include biophobia under the broad umbrella of biophilia, as part of the ensemble that I mentioned.

Q: Since The Biophilia Hypothesis came out in 1993, have there been any genetic discoveries that support the notion of biophilia?

Wilson: I haven't tried to keep up with it beyond that meeting [held in August 1992 at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to discuss biophilia and out of which the book came]. But with work by investigators like Arne Öhman [a psychologist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden who has worked on phobias] and others, they'd already gone into such detail about development and the probable hereditary basis and so on, that the evidence is very strong that way.

Eventually, I think we will know a lot more, including where the genes are located and which fear receptors are activated. I'm pretty sure the fear response will be found to be particularly sensitive to certain inputs, and that will include both pleasurable, emotional feedback and the excitement of fear.

"It's becoming part of the culture to think rationally about saving the natural world."

Q: Do you think, as Gary Paul Nabhan and Sara St. Antoine write in The Biophilia Hypothesis, that the genes for biophilia, if they exist, now have fewer environmental triggers to stimulate their full expression among contemporary cultures than they used to?

Wilson: That's an interesting question. As I pointed out in the chapter on the serpent in Biophilia, the vast majority of people don't ever see a snake in nature. And they're sure not being hunted by cave lions and oversized crocodiles, although they were universally through most of the history of the species. So that part of it is far less true. Also far less true is the chance to unfold more completely a sense of belonging to a habitat, particularly savanna, although that continues to resonate in our making choices for habitation, having city parks, and the like.

So I think that [a sense of biophilia still] resonates strongly, yet probably they are right, it doesn't develop as fully as it did in our ancestors 10,000 or even 5,000 years ago.

AN OPTIMISTIC VIEW

Q: With the world's population exploding, is it still possible for most people to nurture a sense of biophilia? Or is it likely to be just crushed underfoot, particularly among poor people? In the rich countries we have the luxury to think about these things, but what about the peasant farmer in the Amazon who's just trying to feed his family?

Wilson: That is the dilemma of the 21st century—the juggernaut of development, which is extremely hard to stop. The destruction of tropical forests is a good focal point too. (And tropical grassland. Since the 1970s, 80 percent of the tropical grasslands have been destroyed and developed. That's one [ecosystem] we don't think about very much, but tropical grasslands are extremely rich. We don't know how much biodiversity and local ecosystems have gone from that [loss] alone.)

But considering tropical forests, in some parts of the world slash-and-burn [agriculture] has been a key force of destruction. That's particularly true of Africa; that combined with bushmeat hunting is devastating parts of Africa.

We don't need to clear the 4 to 6 percent of the Earth's surface remaining in tropical rain forests, with most of the animal and plant species living there. We don't need to clear that. Any of it. There are ways of taking what's been cleared and devastated, other habitats like saline, you know, with low biodiversity and dry land. The Sahel, the spreading dry country south of the Sahara, begs for the development of dry-land agriculture. Once that gets introduced, even poor people would be better off.

As you can see, I'm a pessimist. No, I'm not a pessimist. [laughs] I'm an optimist.

Q: You are an optimist. But how do you keep optimistic in the face of this juggernaut, as you termed it? And, as you asked in Biophilia, do we humans love the Earth enough to save it?

Wilson: I doubt that most people with short-term thinking love the natural world enough to save it. But more and more are beginning to get a different perspective, particularly in industrialized countries. It's becoming part of the culture to think rationally about saving the natural world. Both because it's the right thing to do—and notice the quick spread of this attitude through the evangelical community—but we will save the natural world in order to save ourselves.

I think the right way of looking at it, and the reason I'm an optimist, is that we still have a lot of elasticity, a lot of wiggle room. The kinds of elasticity and wiggle room that would allow us to save virtually all of the natural environments in the world while dramatically improving ourselves with the land and with the technology yet undeveloped.

Look at this country. This is what I consider real patriotism. Look at the United States of America and say we are at risk from various major movements worldwide of losing our edge, of losing our leadership. We don't need to. We have the greatest scientific minds and capacities in the world. We have experience, and the kind of capitalist system to build technologies swiftly. We can, if we want, lead the world in two areas right away.

One is alternative energy, if we have the will to do it. We can produce the technology that others would beg, borrow, or steal to get. We're in better shape to do it. And we have some elasticity even within our country, so that we're not going to suffer anywhere while we do this changeover.

"Soccer moms are the enemy of natural history and the full development of a child."

The other reason I'm optimistic is what we've been talking about, particularly with reference to the living world. We need a whole new agriculture and silvaculture, the growing of forest, which will take land that has been pretty well ruined as far as natural environments are concerned, and land that's growing dry due to climate change, and develop the crops that can grow in those spreading habitats. The world is going to have to go to dry-land agriculture.

If we can get the crops developed, and find the way—it'll take subsidies at first, you know, prime the pump—to introduce and spread these crops or at least strains of them, replacing the great traditional ones like wheat and potatoes and millet even, we can greatly increase the productivity of [already cleared] lands. I think that's the way we should be thinking, and we should be optimistic about that.

Q: That's refreshing to hear. Getting back to biophilia for a moment….

Wilson: You got me on a soapbox.

Q: No, it's all tied in.

Wilson: I'm happy to tell you, it's getting to be a crowded soapbox. Did you know that Tom Friedman of The New York Times is coming out with a new book this summer? I really like the sound of what he has in mind. He talks like this, but he also is gathering a lot of information to tie together, in something that will appeal to a broad audience, of how we're in an exponential growth phase of so many things: the depletion of resources, the cost of fossil fuels, population, and so on.

All these things are intertwined, and so we have to learn how to look at them as one combined, nonlinear process that's just about going to bear us away unless we handle them now as a whole. I think more and more people are thinking like that. They're deciding that yes, we've really got to face it. And if we do it, there's going to be light at the end of that tunnel. We'll be so much better off.

Q: We'll survive.

Wilson: We'll do more than survive. I think we're going to do very well.

DANGERS OF DISSOCIATION

Q: What could happen to people, to society, if, despite your optimism, we continue to distance ourselves from nature and let our biophilia atrophy?

Wilson: I don't know. There's now a lot of concern, even consternation, among not just naturalists and poets and outdoors professionals but spreading through I think a better part of the educated public, that we've cut ourselves off from something vital to full human psychological and emotional development. I think that the author of Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv, hit on something, because it became such a popular theme to talk about that book [which posits that children today suffer from what Louv calls "nature-deficit disorder"] that people woke up and said, "Yeah, something's wrong."