Gene Robinson said Tutu used his own experience of oppression to understand and empathize with others.

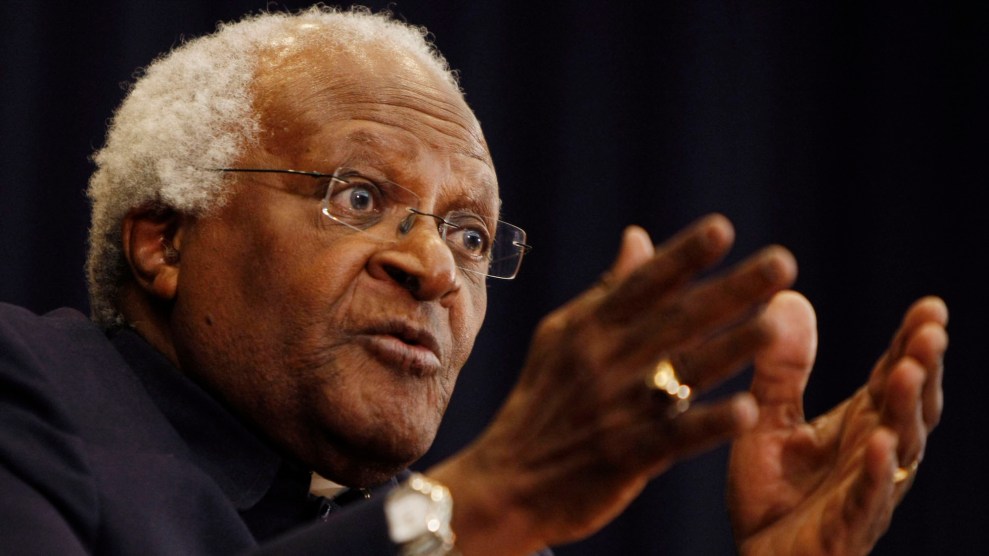

“There was probably at that time, and maybe still, no one better known around the world than Desmond Tutu," Gene Robinson said. | Aaron P. Bernstein/Getty Images

By ASSOCIATED PRESS

12/26/2021

CONCORD, N.H. — In 2008, when the Right Rev. Gene Robinson of New Hampshire was excluded from a global Anglican gathering because of his sexuality, Desmond Tutu, who died Sunday, came to his defense.

“Gene Robinson is a wonderful human being, and I am proud to belong to the same church as he,” Tutu wrote in the foreword to a book Robinson published that year.

Robinson, who in 2003 became the U.S. Episcopal Church’s first openly gay bishop, said Sunday he has been trying to live up to those words ever since.

“It was quite surreal because I was taking grief from literally around the world,” he said in a phone interview. “There was probably at that time, and maybe still, no one better known around the world than Desmond Tutu. It was an astounding gesture of generosity and kindness.”

Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice, died at age 90. He was an uncompromising foe of apartheid, South Africa’s brutal regime of oppression against its Black majority, as well as a leading advocate for LGBTQ rights and same-sex marriage.

“Now, with gay marriage, it’s hard to remember how controversial this was, and for him to stand with me at the very time I was being excluded ... it completely floored me,” Robinson said.

In the foreword to Robinson’s book, Tutu also apologized for the “cruelty and injustice” the LGBTQ community had suffered at the hands of fellow Anglicans.

OBITUARIES

Desmond Tutu, South Africa’s moral conscience, dies at 90

Tutu, Robinson said, used his own experience of oppression to understand and empathize with others.

“He used that as a window into what it was like to be a woman, what it was like to be someone in a wheelchair or for someone to LGBTQ or whatever it was,” he said. “It was the thing that taught him to be compassionate.”

Robinson recalled the way Tutu’s laugh rippled across crowds of thousands as well as a private moment when they prayed together in the seminary Robinson graduated from in New York.

“There was nobody in pain that he wasn’t concerned about, whether that pain was a physical ailment of some kind or a mental illness or something to do with cruelty or degradation. It pained him,” Robinson said. “To sit in the room and hear him praying about those people was about as close to knowing the heart of God as I ever expect to know. I mean, I don’t even need to know more than that.”

Robinson served as the ninth bishop of New Hampshire until his retirement in early 2013 and later as a fellow at the Center for American Progress. Now 74, he recently retired as the vice president of religion and senior pastor at the Chautauqua Institution.

BY SHIRA HANAU DECEMBER 26, 2021 9:17 AM

Nobel Peace Prize laureate and South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu attends a celebration for his 86th birthday on Oct. 7, 2017 in Cape Town, South Africa. (Gianluigi Guercia/AFP via Getty Images)

ADVERTISEMENT

(JTA) — Desmond Tutu, the archbishop who identified closely with the historical suffering of the Jewish people in his forceful advocacy against apartheid in South Africa, died Sunday at age 90.

Tutu, the first Black archbishop of Cape Town, used his role as a church leader to bring religion into the fight against apartheid, South Africa’s repressive system of racial segregation. Advocating for nonviolence and, later, restorative justice, Tutu gained renown far beyond South Africa, earning a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

In the years preceding and during the negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa, Tutu frequently praised the many South African Jews who opposed the apartheid system and worked alongside Black South Africans to transition to an equitable system of governance. He often invoked the Holocaust, comparing the struggles of the Jews under Nazism to the struggles of Black South Africans under apartheid.

Speaking to a gathering of British Jews in 1987, he spoke of that shared experience of exclusion and persecution.

“Your people know what one’s talking about, having suffered because you belonged to a particular racial group. You were forced to wear arm bands. We don’t carry arm bands … they just have to look at us,” Tutu said, according to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency dispatch from the event.

Desmond Tutu during a visit to Jerusalem in December 1989.

But Tutu’s identification with the Jewish people did not spare them from his criticism. While consistently defending Israel’s right to exist and calling on Arab nations to recognize Israel, including when speaking to Palestinian audiences, Tutu was a frequent critic of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and questioned how people who had survived the Holocaust could perpetrate an occupation of another people.

“The Arabs should recognize Israel, but a lot must change also. I am myself sad that Israel, with the kind of history and traditions her people have experienced, should make refugees of others. It is totally inconsistent with who she is as a people,” he said in a 1984 speech at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

Tutu also criticized Israel for continuing to work with South Africa on military matters despite apartheid.

“Israel’s integrity and existence must be guaranteed. But I cannot understand how a people with your history would have a state that would collaborate in military matters with South Africa and carry out policies that are a mirror image of some of the things from which your people suffered,” he said in his 1987 speech to British Jews.

Those comparisons, along with remarks that some Jewish leaders called antisemitic, earned Tutu criticism from some Jewish leaders. In his 1984 JTS speech, he addressed some of that criticism while further fanning its flames with references to a “Jewish lobby.”

“I was immediately accused of being antisemitic,” Tutu said in his speech, referring to the reaction to an earlier speech. “I am sad because I think that it is a sensitivity in this instance that comes from an arrogance — the arrogance of power because Jews are a powerful lobby in this land and all kinds of people woo their support.”

In a 1989 visit to Israel and the West Bank, Tutu made the controversial suggestion during a visit to Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, that the Nazis ought to be forgiven for their crimes against the Jewish people. The suggestion reflected Tutu’s role as the chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which aimed to move the country into a new era by allowing those who participated in apartheid to atone for their sins and to let victims of the system air their grievances and, in some cases, receive reparations.

“We pray for those who made it happen, forgive them and help us to forgive them, and help us so that we, in our turn, will not make others suffer,” he said, according to a JTA dispatch from the time.

Jewish leaders criticized Tutu for his remarks. “For anyone in Jerusalem, at Yad Vashem, to speak about forgiveness would be, in my view, a disturbing lack of sensitivity toward the Jewish victims and their survivors. I hope that was not the intention of Bishop Tutu,” Elie Wiesel said at the time.

(Earlier that year, Tutu had suggested that he and Wiesel could work together to mediate peace in the Middle East.)

Despite his comments, Tutu was frequently honored by Jewish organizations. In 1989, he was honored for his work fighting racial discrimination by the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in New York. In 2003, Yeshiva University’s Cardozo Law School gave him an award for furthering world peace.

In 2009, the same year that then-President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Tutu was disinvited from giving a speech at a Minnesota university over remarks he had made about Jews and Israel.

Abraham Foxman, then national director of the Anti-Defamation League, urged the university not to rescind the invitation.

“Tutu has certainly been an outspoken, sometimes very harsh critic of Israel and Israeli policies, and has sometimes also used examples which may cross the line,” Foxman told JTA at the time. But Tutu “certainly is not an antisemite and should not be so characterized and therefore refused a platform.”

In 2015, Tutu addressed an event hosted by the Israeli organizations Combatants for Peace and the Parents Circle on Israel’s Memorial Day for Israeli and Palestinian parents who lost children to the conflict in a short video speech.

“If change seems impossible, consider our experience in South Africa,” he said. “You can make it happen in Palestine and Israel, too.”

“We and the Palestinians have lost an indomitable fighter, a courageous leader and a moral icon without equal." - #Africa4Palestine Board Member, Professor Farid Esack.

Editor’s Note: The following statement was released by Africa4Palestine on December 26, 2021 on the passing of Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the age of 90.

The human rights organization #Africa4Palestine joins fellow South Africans, Africans and peace-loving peoples across the world in mourning the loss of Archbishop Desmond Tutu – a dear friend of the Palestinian people.

Archbishop Tutu was a close confidant of #Africa4Palestine – someone whom we consulted with, asked for advice and sought support from. Tutu was an ally of all oppressed peoples across the globe and specifically of the Palestinian people in their struggle against Israeli Apartheid.

#Africa4Palestine Board Member, Professor Farid Esack, a personal friend of the Archbishop, commented:

“We and the Palestinians have lost an indomitable fighter, a courageous leader and a moral icon without equal. We are bereft of a prophet who consistently warned against ideas of cheap peace which may come without justice. I am immensely grateful for having travelled and worked with the Archbishop in the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa, in solidarity with the Palestinians against Israeli occupation and in supporting various other causes. His boundless love, his wit and humour and his unflinching and principled commitment to a better world will always inspire us”.

The human rights organization, #Africa4Palestine, pays homage to the life and struggle of our comrade and father, Archbishop Tutu, and we offer our deep condolences to Mama Leah and his children – Trevor Thamsanqa, Naomi Nontombi, Theresa Thandeka, and Reverend Mpho.

We, in a profound and deeply painful way, say “Hamba Kahle” (go well) our leader, inspirer and energiser of the oppressed.

Here is a short video of Archbishop Desmond Tutu addressing a rally for Palestine in Cape Town. The protest march, attended by over 250,000 people, was the largest that South Africa witnessed (on any issue) since the dawn of democracy. The protest march for Palestine was organized by the MJC, ANC, NC4P and #Africa4Palestine together with other organizations. It was attended by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Chief Zwelivelile Mandla Mandela, Ahmed Kathrada, several government Ministers, MPs and others including members of the South African Jewish community.

“Implacable Champion of the Oppressed—and the Fervent Opponent of Tyranny” Desmond Tutu Has Died

Nearly a half-century ago, when apartheid, a racial caste system rooted in colonialism, ruled South Africa, a middle-aged cleric became the first Black dean of Johannesburg, which is an important position in the Anglican church. He could have wrangled a special permit to live in the city’s prosperous white quarter where the church was located, and emerged as a de facto token of phony progress for the racist regime.

Instead, he chose to live in the township of Soweto, home of the impoverished Black working class that made the South African economy hum. Rather than serve as window dressing for the white elite, Desmond Tutu—who died at 90 on Sunday after a 24-year bout with cancer—became its worst nightmare, challenging the system and ultimately helping hasten its demise.

“At a time when the African National Congress’s leadership was either in jail or in exile, there was Tutu—cassock flowing, crucifix swaying front and side, as he strode through the brutality of the townships and the mendacity of apartheid,” the UK journalist Gary Younge wrote in an excellent 2008 profile in the Guardian well worth reading today.

Unsparing in his critiques of the regime, Tutu also preached non-violence and unity among its victims as they sought to overthrow the tyrants. In those years, his routine involved “delivering blistering attacks on the regime one minute,” Younge wrote, and “diving into a crowd to save a suspected ‘informer’ from being necklaced [by anti-Apartheid activist] the next.” He was jailed at least once for his activism; but only for a few hours, possibly because the apartheid regime was wary of turning another political prisoner into a global cause celebre, as it has done with Nelson Mandela.

Even so, using the power of his pulpit and his position on the ground in South Africa’s segregated townships, Tutu emerged as a global celebrity anyway, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. When apartheid crumbled a decade later, the clergyman’s agitations for justice—no matter the popularity of the cause—had only just begun.

He chaired South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which took on the monumental task of delivering justice for apartheid’s crimes without tearing up a racially divided society. The strategy was to give the regime’s victims the chance to formally testify and document the wrongs done to them and receive reparations, and allow the perpetrators the opportunity to seek amnesty after admitting their crimes.

Formally concluding in 2001, the TRC left behind a complex legacy. For Black South Africans, the televised hearings provided “an acknowledgment of the daily horrors that they were subject to during apartheid,” Ereshnee Naidu-Silverman, senior director for the Global Transitional Justice Initiative, wrote in a 2019 Washington Post op-ed. “With testimony from 21,000 victims, the 2,000 public hearings and 7,112 amnesty applications made it difficult to cling to denialism because a collective narrative of a racist past began to emerge.”

Yet the TRC’s call for broad-based reparations for Black South Africans ended up being ignored by the government, while few perpetrators admitted to crimes or were punished for them, she writes. Still, the commission remains a model for societies trying to peacefully move beyond systemic wrongs in a just way—imagine if the United States had held public hearings, say, on the horrors of the Iraq War or those of the Jim Crow era.

In the 2000s, Tutu remained an outspoken crusader for justice, repeatedly clashing with the ruling African National Congress, which ruled South Africa after apartheid, over various corruption scandals. Tutu also used his platform to speak out on a range of global affairs, from the Israeli occupation of Palestine to the Iraq War, which he opposed from the start; from toothless international climate policy to homophobia within religious institutions.

Younge’s 2008 profile paints him as a playful, introverted man who really just wanted to be loved. “They call him Father, but as he sits at the breakfast table eating Cheerios with fruit and yogurt, giggling as he teases and is in turn teased, Archbishop Desmond Tutu looks more like a mischievous little boy,” Younge wrote. “He has been known to bust out a dance move whether or not there is a dancefloor in sight.”

He remained active well into his 80s. “Ever the rebel, he came out in support of assisted suicide in 2014, stating that life should not be preserved ‘at any cost,'” reports the BBC in its obituary. “In 2017, Tutu sharply criticised Myanmar’s leader and fellow Nobel Peace laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, saying it was ‘incongruous for a symbol of righteousness’ to lead a country where the Muslim minority was facing ‘ethnic cleansing.'”

Tutu is gone, but his memory—and if we’re lucky, his example—will live on. For him, using his voice to defend marginalized people against oppression was a kind of vocation, a life’s work. And so was maintaining a sense of humor.

President Joe Biden has not yet released a statement, but former President Barack Obama wrote:

No comments:

Post a Comment