Memory Lane: The 1958 miners' strike, or the year Sudbury almost didn't celebrate Christmas

Vicki Gilhula

SUDBURY.COM

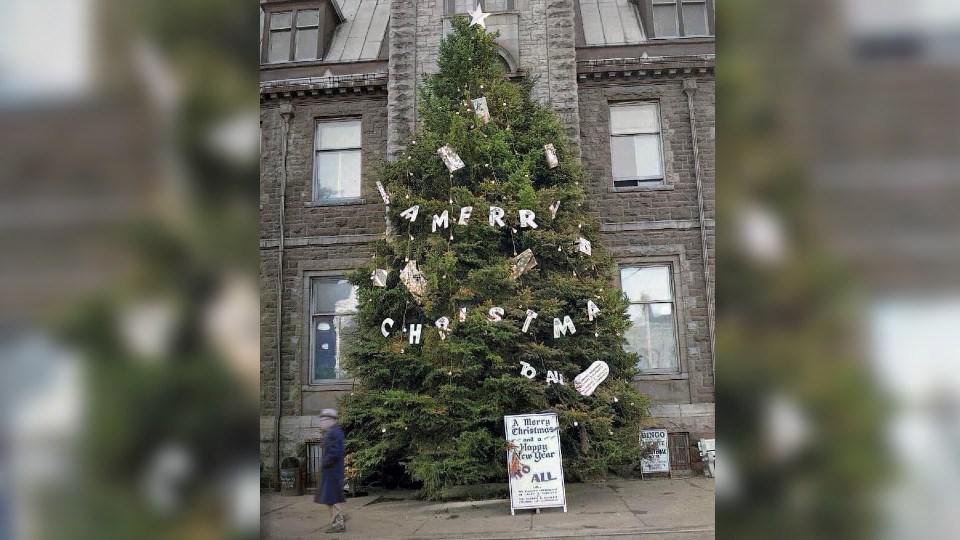

Members of Mine Mill Local 598 were on strike for three months in 1958.

Members of Mine Mill Local 598 were on strike for three months in 1958.

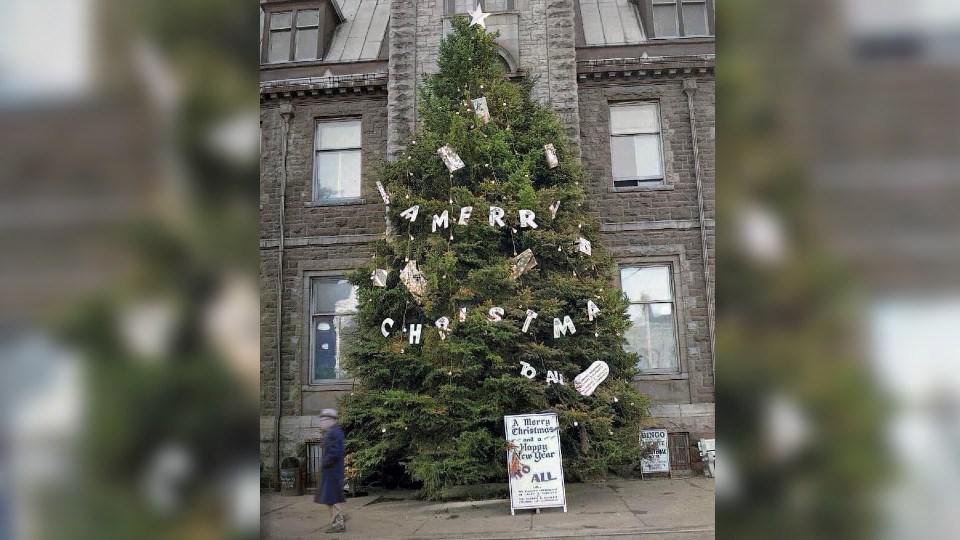

The strike was settled days before Christmas.

Greater Sudbury Public Library collection

At a children's party in December 1958, a five-year-old whispered her Christmas wish to Santa Claus. She wanted what everyone in Sudbury wanted: an end to the strike at Inco.*

Just days before Christmas, Mine Mill Local 598 president Mike Solski and national president Nels Thibault returned by train to Sudbury from Toronto to announce an agreement had been reached with a three-year contract and a six-per-cent wage increase over three years on offer.

A small group of 100 people braved -28 C temperatures to welcome the men at the downtown train station. They sang "Solidarity" and hoisted Solski on their shoulders.

Sudbury.com invites readers to share memories of the Strike of 1958, and in particular, stories of kindness and charity in a time of hardship. Memories can be sent to mgentili@sudbury.com or vgilhula@gmail.com. A follow-up article will be published later this month.

Most miners, as well as city politicians, did not think there was going to be a strike. There had been labour peace since Mine Mill signed its first contract in 1944. The company had offered wage increases in all previous contracts.

Earlier in 1958, Inco laid off 1,300 workers and another 300 after contract talks began. At the time of the strike, miners were working a 32-hour week as an alternative to losing another 2,500 jobs.

The union asked for a 10-per-cent increase on the hourly rate. Inco's opening offer was no wage increase in keeping with the Conservative government's “Hold the Line on Wages” policy during an economic recession.

As autumn approached, union leaders asked members for a strike mandate. They voted 83 per cent in favour of a strike action during a vote held Sept. 12 and Sept. 13. When contract negotiations broke down Sept. 16, the union called for a strike.

The impact of a strike at the city's biggest employer was almost impossible to imagine.

Mayor Joe Fabbro called an emergency council meeting to ask the Ontario minister of labour to intervene and reopen talks.

The mayor also called for a special day of prayer on Sunday, Sept. 21 to ask for guidance and help to find a solution to the labour troubles.

Politicians and prayers could not stop pickets from being set up Sept. 24 at Copper Cliff, Creighton, Levack, Garson, Frood-Stobie and Coniston. An estimated 14,000 workers in Sudbury and 1,200 in Port Colborne were now dependent on strike pay.

Meanwhile, Inco had a stockpile of nickel that could last until spring. How long the strike would continue was anyone's guess.

Miners' wives were called into action. They went out to work if they could find jobs. They organized clothing drives and made sandwiches and coffee for the men at union halls in Sudbury, Garson, Chelmsford, Coniston and Creighton.

December 1958 was colder than usual with temperatures 17 degrees below normal. In the weeks before Christmas, Mine Mill handed out 8,000 food vouchers, The Salvation Army and city churches collected food, fuel and clothing for strikers' families.

Sudbury Barbershop Singers raised $15,000 during the holiday season to purchase toys for children. This was about 50 per cent more than the year before.

Christ the King Church started an adopt-a-family program. Unions in Toronto, Hamilton, Guelph and Peterborough donated 58 tons of food.

Local businesses made donations of cash and supplies. Some companies cancelled staff holiday parties and gave the funds to those in need. Families borrowed money from family and friends.

The contract was ratified Dec .22. Even the most cynical observer would have to admit the end of the three-month strike seemed like a Christmas miracle.

On Christmas Eve stores in Sudbury were particularly busy with last-minute shoppers. Churches were filled to capacity the next morning.

Community leaders had been afraid Sudbury would be crushed by a strike at Inco. An estimated $8 million in purchasing power was lost, but no business bankruptcies were reported.

People moved away to find work elsewhere. Some families lost their homes. There was an increase in requests for social assistance and the poverty rate increased by 10 per cent. But as The Globe and Mail reported Dec. 22, 1958, no one starved or froze to death. No one had their heat, hydro or telephone cut off.

Mine Mill Local 598 was left almost bankrupt and this set the stage for the later raids by the United Steelworkers of America.

Sudbury had survived its worst nightmare although it would take at least a generation before the community would heal the divisions caused by the 1958 strike.

Vicki Gilhula is a Sudbury freelance writer and a former editor of Northern Life and Sudbury Living magazine. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.

Sources

* The Globe and Mail, Godfrey Hudson, (Dec. 22, 1958), Quiet Elation in Mining Belt: End of Strike Brings Thanksgiving Prayers in Sudbury.

The Globe and Mail, Wilfred List, (Sept. 18, 1958), Walkout set for Sept. 24: Nickel strike by 15,000 alarms Sudbury.

The Globe and Mail, Muriel Snider,(Dec. 23 1958), Sudbury's Independence: The 'Prestige' strike left city apathetic.

The Globe and Mail, Joan Hollobon. (Dec.16, 1958), Financial blow: Sudbury residents facing bleak Christmas as result of Inco strike.

The Globe and Mail, Inco strike hit hearts and minds, survey shows, (Dec. 22, 1958).

At a children's party in December 1958, a five-year-old whispered her Christmas wish to Santa Claus. She wanted what everyone in Sudbury wanted: an end to the strike at Inco.*

Just days before Christmas, Mine Mill Local 598 president Mike Solski and national president Nels Thibault returned by train to Sudbury from Toronto to announce an agreement had been reached with a three-year contract and a six-per-cent wage increase over three years on offer.

A small group of 100 people braved -28 C temperatures to welcome the men at the downtown train station. They sang "Solidarity" and hoisted Solski on their shoulders.

Sudbury.com invites readers to share memories of the Strike of 1958, and in particular, stories of kindness and charity in a time of hardship. Memories can be sent to mgentili@sudbury.com or vgilhula@gmail.com. A follow-up article will be published later this month.

Most miners, as well as city politicians, did not think there was going to be a strike. There had been labour peace since Mine Mill signed its first contract in 1944. The company had offered wage increases in all previous contracts.

Earlier in 1958, Inco laid off 1,300 workers and another 300 after contract talks began. At the time of the strike, miners were working a 32-hour week as an alternative to losing another 2,500 jobs.

The union asked for a 10-per-cent increase on the hourly rate. Inco's opening offer was no wage increase in keeping with the Conservative government's “Hold the Line on Wages” policy during an economic recession.

As autumn approached, union leaders asked members for a strike mandate. They voted 83 per cent in favour of a strike action during a vote held Sept. 12 and Sept. 13. When contract negotiations broke down Sept. 16, the union called for a strike.

The impact of a strike at the city's biggest employer was almost impossible to imagine.

Mayor Joe Fabbro called an emergency council meeting to ask the Ontario minister of labour to intervene and reopen talks.

The mayor also called for a special day of prayer on Sunday, Sept. 21 to ask for guidance and help to find a solution to the labour troubles.

Politicians and prayers could not stop pickets from being set up Sept. 24 at Copper Cliff, Creighton, Levack, Garson, Frood-Stobie and Coniston. An estimated 14,000 workers in Sudbury and 1,200 in Port Colborne were now dependent on strike pay.

Meanwhile, Inco had a stockpile of nickel that could last until spring. How long the strike would continue was anyone's guess.

Miners' wives were called into action. They went out to work if they could find jobs. They organized clothing drives and made sandwiches and coffee for the men at union halls in Sudbury, Garson, Chelmsford, Coniston and Creighton.

December 1958 was colder than usual with temperatures 17 degrees below normal. In the weeks before Christmas, Mine Mill handed out 8,000 food vouchers, The Salvation Army and city churches collected food, fuel and clothing for strikers' families.

Sudbury Barbershop Singers raised $15,000 during the holiday season to purchase toys for children. This was about 50 per cent more than the year before.

Christ the King Church started an adopt-a-family program. Unions in Toronto, Hamilton, Guelph and Peterborough donated 58 tons of food.

Local businesses made donations of cash and supplies. Some companies cancelled staff holiday parties and gave the funds to those in need. Families borrowed money from family and friends.

The contract was ratified Dec .22. Even the most cynical observer would have to admit the end of the three-month strike seemed like a Christmas miracle.

On Christmas Eve stores in Sudbury were particularly busy with last-minute shoppers. Churches were filled to capacity the next morning.

Community leaders had been afraid Sudbury would be crushed by a strike at Inco. An estimated $8 million in purchasing power was lost, but no business bankruptcies were reported.

People moved away to find work elsewhere. Some families lost their homes. There was an increase in requests for social assistance and the poverty rate increased by 10 per cent. But as The Globe and Mail reported Dec. 22, 1958, no one starved or froze to death. No one had their heat, hydro or telephone cut off.

Mine Mill Local 598 was left almost bankrupt and this set the stage for the later raids by the United Steelworkers of America.

Sudbury had survived its worst nightmare although it would take at least a generation before the community would heal the divisions caused by the 1958 strike.

Vicki Gilhula is a Sudbury freelance writer and a former editor of Northern Life and Sudbury Living magazine. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.

Sources

* The Globe and Mail, Godfrey Hudson, (Dec. 22, 1958), Quiet Elation in Mining Belt: End of Strike Brings Thanksgiving Prayers in Sudbury.

The Globe and Mail, Wilfred List, (Sept. 18, 1958), Walkout set for Sept. 24: Nickel strike by 15,000 alarms Sudbury.

The Globe and Mail, Muriel Snider,(Dec. 23 1958), Sudbury's Independence: The 'Prestige' strike left city apathetic.

The Globe and Mail, Joan Hollobon. (Dec.16, 1958), Financial blow: Sudbury residents facing bleak Christmas as result of Inco strike.

The Globe and Mail, Inco strike hit hearts and minds, survey shows, (Dec. 22, 1958).

No comments:

Post a Comment