Mr. Blue and Maria: A Musical Dream

(a dreamscape)

Sixty years ago in the late fall and early winter, a seventeen-year-old blue-eyed Bronx boy went by himself to see an afternoon showing of West Side Story on Fordham Road in the north Bronx. He took the bus to the theater but walked the few miles home in a romantic daze, in love with Maria and yearning for a girl like that for himself. The movie had mesmerized him, and though he knew about gang fights and the enmity between different ethnic groups, especially white prejudice against Puerto Ricans and blacks, he had never been involved in such violence. It was real and not-real for him, and he was smart enough to realize that a movie was not real life and that great music had the anodyne power to enchant, and together with colorful moving pictures it could put one into a dream state that could be very powerful. There was a reason why Hollywood was called the “Dream Factory.” But he liked to dream and went to the movies to lose himself in fantasy like so many others. But West Side Story had hit him especially hard, and as he walked home through the winding streets, he felt unreal, as though the spell the movie cast on him was everlasting. He wanted to be Tony, not dead but alive, and Tony taking Maria away from the violent streets to a somewhere place where love and happiness were possible. His fascination, however, was tinged with foreboding, a sense that despite what felt like a window of optimism and hope in 1961 with the new young president John Kennedy in the White House, something bad was coming round the corner or whistling down the sky since shortly before the U.S. and the Soviet Union had faced off with tanks at the recently erected Berlin Wall, and weird things were happening around the world such as the Bay of Pigs invasion earlier in the year and the recent death of the Secretary General of the UN Dag Hammarskjöld, one of the boy’s heroes. In those years before cynicism swept the country, people had heroes, as did the boy: his father, JFK, Hammarskjöld, Paul Newman, and the basketball star Bob Cousy, obviously different in kind and stature. For the boy was a romantic at heart but his head thought dark thoughts. He didn’t know why, but he felt an odd mixture of hope and dread, and he kept thinking of Tony and Maria and how they fell in love at first sight. He wondered if this was just a movie thing. Was it fate that Tony got shot? He kept thinking back to seven years earlier when his seven-year-old cousin accidentally shot and killed his nine-year-old brother and the weirdness of accidents and horrible evil and love and sex and death and how his blue-eyed red-haired sister had married her Puerto Rican boyfriend despite the sick norms of the time – his mind was a merry-go-round of inchoate thoughts and impressions going in circles till the music stopped when he got home without a partner to share his deepest thoughts with, and no hand to hold – and so he went twice more by himself to see the movie, hoping to discover some secret embedded in its tale, thinking that perhaps the beautiful music hid a revelation and so he would have to listen again and again. He kept all this to himself, not daring to share his heart’s desires and fears with anyone, since he was an athlete and the only boy with seven sisters and his role was to be strong and brave and stoic and swallow his loneliness. The previous month he had come out of high school basketball practice on East 85th St. in Manhattan in the early evening only to ask a stranger for the time. The stranger in the tan cap and coat was his hero Paul Newman, the star of the recently released movie The Hustler in which he played Fast Eddie Felson, the pool hustler. The boy, who loved movies and went dreaming in them, had identified with Newman and his character’s desire to win, and when Newman, who introduced himself as Paul, very nicely took a few minutes to ask his name and talk to the boy about his school and basketball, the boy was thrilled, and the thrill was compounded when Newman called after him as the boy was leaving, “See you later, Fast Eddie.” They shared blue eyes and for some reason blue now seemed to color so much of what the boy saw and felt, the blue of the open sky’s freedom and the blueness of Tony’s eyes and his death and the Virgin Mary blueness of the aptly names Maria of the dark eyes, just like the talismanic miraculous medal of Blessed Mary that hung around the boy’s neck, kept there to protect and guide him to something that felt just out of reach and that perhaps he needed a miracle to reach. Who knows? He didn’t, but he felt that something was coming if he could only wait in hope, something very hard to do with his impetuous and passionate nature. He had just gotten into a stupid fight at a basketball practice with Louis Alcindor, who later became Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, which left him feeling weird and wondering about young men and fighting and now he had just seen Tony get killed in a tragic twist of fate in a game run by forces bigger than the Sharks and the Jets could imagine. What did it mean to win? And even though Tony wasn’t real, only an actor playing a part, his death resounded in the boy’s mind, just as did Maria’s anguish as she held her dying lover. Somewhere someday, he thought, love might conquer all this madness and we’ll find a new way of living and I’ll find my Maria and it will be love at first sight. The next year the boy went with a friend to The Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village. It was around the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis when the world teetered on the edge of nuclear war. The unknown blue-eyed Bob Dylan was performing there that fall and it was when he first sang “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” The boy kept hearing his words: “And what’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son? And what’ll you do now, my darling young one?” And a hard rain did fall, although nuclear war was avoided, Kennedy was soon shot dead for seeking peace between two gangs far more deadly than the Sharks and the Jets. And the boy had to decide what he would do, for the music played on but nobody was listening and there were guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children and napalm and rifles in the hands of young men in distant jungles. He wondered if there really was a place for us somewhere, a place to find a new way of living, for it didn’t seem like this was the time for it with blood everywhere, bad blood, good blood, puddles of blood, streams of blood, blood in the songs and songs in the blood, Dallas, New York, Memphis, the city of Angels, Saigon, San Juan, Hanoi down through the years as he wandered in tears and wondered where it was all going, all this blood. Blue entered his soul, a blueness of the deepest deep that was not a technicolor blue but a Billie Holiday blue, the Bronx buried Billie near the boy’s dead young cousin Jimmy, dead with a bullet to the heart because of an adult’s carelessness, the adults who made the wars in the ghettos and the jungles and caused the deaths of so many all across the world, those unfeeling ones who killed Billie and Bobby and Jimmy and Tony and Johnny and Bernardo, and did their best to try to extinguish blue skies in the hearts of young people everywhere, to drug them and wipe their minds clean of hope and idealism and the feeling that miracles could happen and the world is full of light with suns and moons all over the place, wild and bright going mad, shooting sparks into space because love is found and love abides. For the boy, as he walked through the years and became a man, the blueness in his soul always also harbored a certain blue that counteracted the blues, a blue like singing the blues defeats the darkness. For him it was this inner image of Maria, Mary, Marie, the lady in blue, the Blessed one, the mother of all sorrows and hope that kept him company all along his journeys and sang to him as she held his hand. Who can explain it, who can tell you why? He wasn’t foolish enough to try. One day, the boy who became the man, now a reluctant young professor, walked into a room to teach a course on death and meaning, and there was his beautiful Maria looking at him, she of the long dark hair and dark eyes, resurrected, and he saw her and the world went away, death departed, they stared at each other spell-bound, and he knew this wasn’t a movie but was real love at first sight. Time flew away and yet a hard rain kept falling and it’s falling still. The sky still weeps and the blood keeps a-flowing. The boy learned to tell it and “speak it and think it and breathe it and reflect from the mountain so all souls can see it,” and is still doing his best. He and Maria, no longer young, just went to the movies together to see the remake of West Side Story. The theater was nearly empty. He was expecting to find much to criticize. Instead, he found Tony and Maria again and the same old story, the fight for love and glory for a new time and place but with new faces in the same race to defeat the old hate that never seems to die. It was only a movie. But as he took Maria’s hand he knew that love abides, and he whispered to himself: “Always you, every thought I’ll ever know/Everywhere I go you’ll be, you and me.” It was a miracle, not a dream.

The Joys and Sorrows of Being a Celebrity Fan: James Dean, Jerry Lee Lewis and Mickey Mantle

No one who frequents the dark auditorium is really an atheist

— Edgar Morin, Marxist Movie Critic

Orientation

Cross-cultural uniqueness of celebrity culture

If members of a tribal society during Paleolithic or Neolithic times, or even members of Bronze Age Egypt or Mesopotamia had heard about the United States population’s devotion to celebrities, they wouldn’t believe it. How could you become attached to a person you will never meet, whose shelf life might be five to 10 years and who doesn’t know or care about your life? How can it be that during a period of adolescence these celebrities might be more important than one’s family, relatives, friends? What if we told these ancient peoples that these celebrities came to be seen as more interesting than religious or political authorities? Again, disbelief. This article is partly experiential description of how that process of creating and sustaining celebrities came to be.

Questions about the differences between fame and celebrity

Is it possible to be famous without being a celebrity? Is it possible to be a celebrity without being famous? What is the place of mass communication in developing notoriety? Can a person be famous without the presence of mass communication?

What about the place of fans? Can you be famous without having fans? What is the relationship between charisma, sex appeal, and competence? Is it possible to be famous and not have charisma? Is it possible to be a celebrity and be incompetent?

Is there any difference between the psychological health of people who are famous as opposed to those who are celebrities? How relevant is capitalism to notoriety? Can there be celebrities without capitalism?

The place of celebrity in adolescent socialization

Every young boy or girl is socialized by different forces. Sociologists name at least seven sources of socialization: the family, the state, and religious authorities are usually the most conservative of forces. Liberal forces of socialization include education, friends, advertising, and celebrity culture (including movie heroes and heroines, sports figures and movie stars). Contrary to what you might expect, sociologists have found that neither advertising nor movie stars, sports figures nor musicians could compete with the more long-standing sociological forces of family, religious organizations, the state or education in terms of the internalization of values. However, this celebrity culture could definitively involve sidetracking the individual.

When I was about ten years old, like most middle-class kids of the late 1950s, I had my own room, and I could hang any pictures on the wall that I wanted. Who was on that wall? Was it a picture of my parents, grandparents or other relatives? Are you crazy? Were there pictures of the American flag or a crucifix? Not on your life! Were there pictures of my teachers? My teachers were nuns. If I ever got hold of a picture of them, it would be used as a dart board. My friends? We are getting closer, but friends were to be played with, not frozen into photographs. I had three huge posters on my wall. One of a sullen James Dean looking down; another of Jerry Lee Lewis burning down his piano, and the last of Mickey Mantle connecting for another long home run (the picture at the beginning of this article). What the movie stars, musicians, and baseball players meant for my socialization is also the subject of this article.

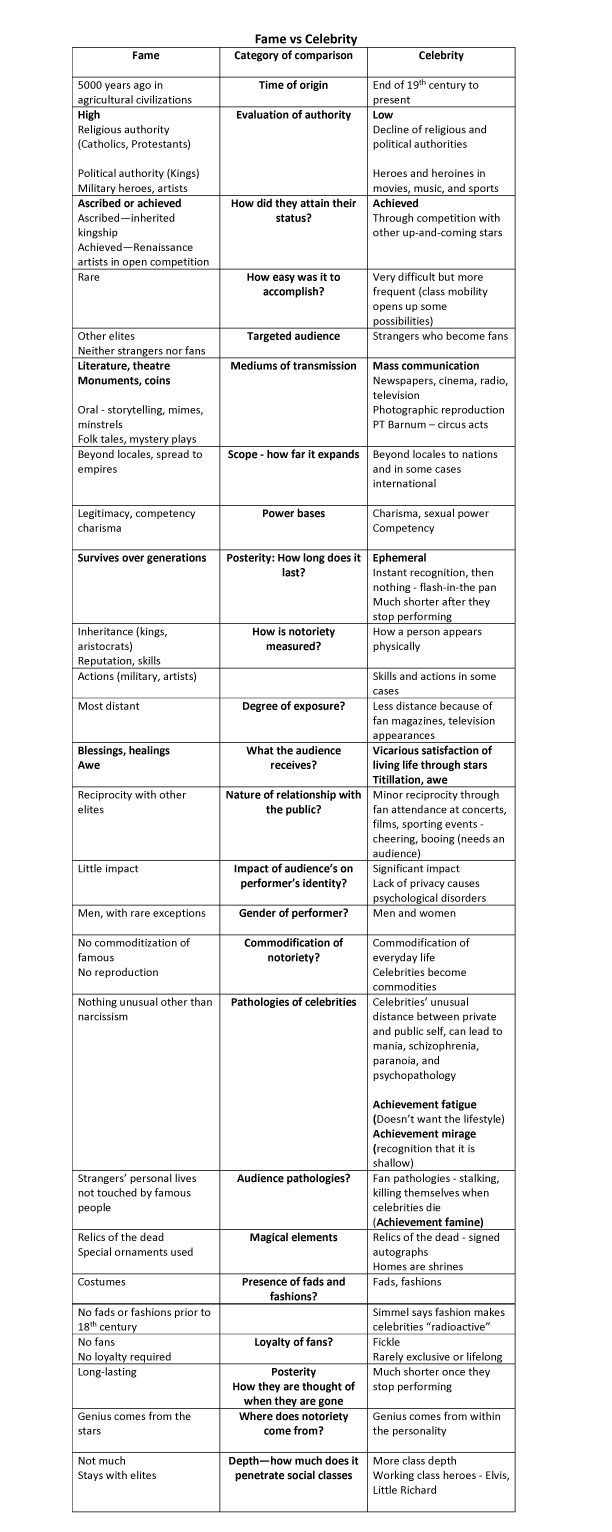

Fame vs Celebrity

From my research into two books, The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History by Leo Braudy and Celebrity by Chris Rojek, I found some interesting differences between what it means to be famous, what it means to be a celebrity. What both forms of notoriety have in common is their relationships with the public:

- have a lopsided epistemology with the notorious person knowing nothing about those who follow them; or

- what relations exist are thin, lack any thickening or deepening of communication.

What is fame?

There are four elements of fame according to Leo Braudy: a person, an accomplishment, the immediate publicity that surrounds the event or person, and posterity (how they are thought of beyond their lifetime). For most of human history, fame existed without celebrity. Fame was based on legitimate social sources. For example, religious authorities like popes or cardinals could be famous. Political authorities like Solon, the Athenian statesman, lawmaker and poet, or Pericles were famous. Lastly, military heroes could be famous. Beyond the ancient world, competing Renaissance artists became famous. One of the characteristics that creates a celebrity is mass media, which was absent for most of human history. Without mass media, the public was reminded of famous people through the minstrel storytelling, literature, and by attending theater or by being forced to look up at towering monuments. Lastly, fame could be spread by the circulation of coins with the emperor’s picture on them.

How did the person become famous? This occurred as the result of great deeds, by the spreading of their reputation among elites, or through rumor or gossip. Fame did not easily spread to faraway places until the rise of the printing press, newspapers, and the telegraph. The status of famous people could be either ascribed or achieved. Ascribed status such as the divine right of kings or a religious authority who inherited their office, or an aristocrat passing down his land to his son. Achieved fame can be fame that came to an individual because of their skill. A religious, political or military authority could become famous because of religious reforms, outstanding political maneuverings, or military strategies or tactics.

The percentage of people who became famous was minuscule compared to the size of their populations. People who were famous had next to no interaction with the public except to pass by them as part of a military parade or a pageant. Their social interaction was limited to other elites. In other words, there were no fans of famous people. Fans are a product of celebrity culture, as we will soon see. The power bases of famous people were either legitimacy or competency, with charisma or sexual power being a secondary source. Force, coercion or economic power are usually not ingredients in becoming famous. Famous people offer blessings (the magic touch of the king) or healings. Famous people have nothing to do with impacting the personality of the people who admire them, as happens with celebrities. People are famous for generations. There are no flash-in-the-pan famous people. Religious, political and military elites live in little worlds of their own. With rare exceptions, the overwhelming majority of famous people were men, and they were subject to neither fads nor fashions, as was the case at the beginning of the 18th century.

What is a celebrity?

At the end of the 19th century a new kind of notoriety appeared, celebrity. Celebrity grew from the ashes of the decline in respect for religious and political authorities. Celebrities are not members of traditional elites. There are no such things as ascribed celebrities, as the competition to be in the movies, sports or music is fierce. Unlike famous people, celebrities are extremely well-known and this is due to the presence of mass media. National newspapers, magazines, movies, radio, and later television gave new celebrities an instant and expanding audience. However, unlike famous people, the life of celebrities is very-short lived. The shelf-life of movie stars is relatively brief, especially for women. It is rare for movie stars to capture the public’s attention for more than a few years, if that. When I think of Rhythm and Blues musicians, their hits won’t last more than about five years. People like Ray Charles or Van Morrison are the exceptions. After that, musicians go on the road as nostalgic acts, if they are lucky. When it comes to baseball, the time for the stars might be a little longer – ten to fifteen years. After that, fans are on to new flames. Unlike as with famous people, the power bases of movie stars are charisma and sexual attractiveness, in addition to competency. While most famous people were overwhelmingly men, there is more of a balance between men and women in the life of a celebrities.

Celebrities also developed as the U.S. population searched for a new kind of transpersonal identity that was necessary as the industrial revolution ran roughshod over urban communities. It is no accident that sports teams and the cinema were both product and producer of public needs beginning at the end of the 19th century. Famous people did not have fans. Fans are a product of the public’s ongoing vicarious involvement with the movies and their stars, musicians and their bands, and sports superstars and their teams. All this could not be possible without mass media. Celebrities have a special kind of relationship with their fans that famous people did not have with their public.

Fans help to make celebrities larger than life with their turnouts at the Academy Awards, ball games and concerts. However, fans can make the lives of celebrities a living hell, allowing them no private life. It is not surprising that celebrities acquire psychological disorders like narcissism, paranoia, or drug addiction disproportionate to the population (Chris Rojek). Magazines like People keep tabs on celebrities and hold interviews in which the stars “open up” about their traumas, disappointments, and recoveries. There were no fashions prior to the 18th century. Before then, people simply wore the clothes of their social class. It wasn’t until advertisers got control over newspapers, magazines, and radio that they were able to suggest that the public has the right to wear whatever they want. Furthermore, that clothing could be rotated with the changing of the seasons. As for fads, they are the product of mass communication and where trends begin. Celebrities are both producers and products of fads and fashions.

Theories of celebrity

Chris Rojek reviews at least five theories of celebrity. The first theory is subjectivist, claiming that celebrity status is the product of the celebrity’s personality, their possession of charisma. This is a cultural version of the “great man” theory of history. The second theory is that of the Frankfurt School. This sees the function of celebrities and star culture as a means for socially controlling the masses. For example, it is no coincidence that there are rarely celebrities in movies or music who aspire to group emancipation. Celebrities promote individualism.

For Edgar Morin, French philosopher and sociologist of the theory of information, celebrities are not under the control of elites but rather they are the projection of the pent-up needs of the audience themselves. For Morin, celebrities are the transformers, accumulating and enlarging the dehumanized desires of the audience. For D. Marshall and J. Gamson, the main emphasis is neither the charisma, the social control of elites, nor the needs of the audience. Rather the mass media itself is a force to be reckoned with as they have their own capitalist interests for keeping celebrity culture alive. Lastly, the foundational types of character theory of Orrin Klapp argue that audiences don’t just have individual needs, but group needs as well. The audience is made up of members of social groups that develop character types that have an impact on the kind of roles that appeal to audiences. For example, the “good Joe”, the villain, the tough guy, the snob, the prude, and the love queen are both the result of the audiences’ private life that are projected on to the characters, as movie makers have learned to adapt their movie characters to these expectations. Hollywood Movie Stars

Hollywood Movie Stars

Brief evolution of the star system

According to Edgar Morin in his book The Stars, the first movie stars in silent films participated in very simple movie plots which were a combination of fantasy and melodrama. The first stars resembled a kind of distant royalty. The mood of the early movies was pessimistic and tragic with the audience mostly composed of popular and juvenile audiences. After 1930, plots became more complex and realistic. There was less reliance on occult causes of events and the appeal was more psychological. After the Great Depression in the 30s, movie producers felt pressure to make movies that had happy endings. Movies lost some of their bad associations with burlesque and started to appeal more to a middle-class audience. The gap between the movie stars and the audience began to shrink as audiences wanted their star gods, but still wanted them to have at least some of the same types of personal problems that they had. Stars were still viewed as considerably above audiences, but Morin now called them a “constitutional monarchy of lesser stars.” The stars greatly resembled the gods and goddesses of classical Greece. They were not of a higher moral order. They had the same problems as the audience, except on a higher larger scale. The gods and goddesses had affairs and there were scenes of betrayal, war, peace, and adventure.

One interesting side effect was that the presence of movie stars on the big screen impacted the expectations the public had about their criteria for dating. As people went to movies and bought up movie magazines with touched-up pictures of the stars, boys and girls started expecting their dating partners to measure up to their movie idols, both physically and emotionally. Fans were less interested in dating people like themselves.

Four types of audience-star relationship

In his book Stars, Richard Dyer cites the work of Andrew Tudor, Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of York, who suggested four types of audience-star relationships:

- Emotional affinity – this is the most common and involves a loose attachment between the star, the storyline, and the personality orientation of the audience.

- Self-identification – the audience places themselves in the same situation as the star. They imagine themselves on the screen, experiencing what the stars are experiencing.

- Imitation – most common among young teenagers and takes the relationship beyond cinema, with the star acting as a life-model for the audience. Fans mimic the star’s clothing, hairstyle, and leisure activities.

- Projection – “star-struck” – the public lives their life as if they were the star. The real-world and the star-world gets reversed. The fans ask themselves “what would the star do?”, before swinging into action.

Idol 1: Movies, James Dean

The process by which I found out about James Dean is embarrassing. It wasn’t that I had watched the movie, Rebel Without a Cause, and fell in love with him. It was a large poster-sized picture of him in a music store that caught my eye. He was looking down and brooding. I think I also saw a picture of him in a motorcycle jacket, which I think was the clincher. Years later I watched the movie and while I liked it, I couldn’t identify with it. His family was upper-middle class and they lived in a big house. Dean was very inarticulate, and I couldn’t understand what he wanted from his father. I was mad at my parents for sending me to a Catholic school, but I didn’t feel they misunderstood me. Still the theme of rebelling against the authorities – in my case the Catholic Church – was good enough for me. When my parents saw the larger-than-life poster on the wall, they didn’t like it. They may have understood what the picture meant better than I did. Naturally enough, their disapproval reassured me I was on the right track!

Why did I idolize him?

What did it mean to idolize him? For one thing, he let me know that I was not alone with my problems. Also, these problems had to do with my age. Teenagers were supposed to be unhappy. The fact that he was a movie star, plastering his unhappiness in interviews, photographs, and newsreels, let me know this was a national problem. Now I certainly had friends who were unhappy like I was, but why wasn’t knowing and talking to them enough? It’s because friendships required work. You had to listen to them, and many could not really appreciate my problems. With a movie star, not only did I not have to listen to him, but I could project the image of a perfect older brother, a teen-age listener who understood everything. No matter what problems I was having with my parents or teachers in school, I could always come home from school, go in my room, close the door, and James would be there, reassuring me that everything was bullshit.

Application of theories of celebrity to James Dean

In terms of theories of celebrity, James certainly had charisma, but I don’t think that the function of his stardom was for social control as the Frankfurt School argues. Being a rebel against the conformity of the early 50s was cutting edge. Sure, it was about individual not social rebellion, but the social movements of the 60s were just getting started. I didn’t feel Morin’s theory applied either. I did not feel Dean was an expression of some pent-up dehumanized life I was leading. I’m sure that Dean would have fit into Orrin Klapp’s social type as an outsider. But the problem is that if these types are always operating as Klapp claims, what were the conditions of the early 50s that made these rebel movies such hot items? After all, Marlon Brando and others were selling rebel movies as well. Klapp has no answer for this. Besides Dean’s charisma, Marshall ‘s and Gamson’s mass media self-interest was very present. It was the bombardment of Dean’s image, not just in movies, but on billboards and posters that drew me in. Perhaps the biggest favor that no theory covers was the close relationship of our ages. I must have been about 16 and Dean must have been about 25, still within the range for me to identify with him. He was a perfect rebel for me because I was at an age when rebellion was starting to almost be expected.

What kind of fan attachment to Dean did I have?

Relative to the types of audience attraction, my connection to Dean was mild emotional affinity. I did not know about his personal life, let alone try to imitate it. I can say that I copied his hair and clothing that was uniquely his. Having a pompadour and wearing motorcycle jackets was a dark, but attractive side of the late 1950s culture. So it wasn’t because of James Dean alone that I dressed like him.

Idol 2 Music: Jerry Lee Lewis

Musician celebrities had a much more powerful impact on me than movie stars, because listening to music is the most powerful of all the arts in altering states of consciousness for me. Jerry Lee appealed to me because of his raw rebelliousness. Whether it was Great Balls of Fire, Whole Lotta Shakin Going On or Breathless, this seemed like a guy who didn’t give a fuck. Jerry Lee was everything the Catholic Church was opposed to. Wild hair, oozing sexuality, surely on a path to Hell. Jerry even admitted that during different parts of his career that he played “the Devil’s Music”. What more can a 10-year-old boy want! But beyond Jerry Lee all the other musicians, whether it was rhythm and blues or rock and roll, music offered me a temporary ticket out of the life I was living. I cannot say that they opened my horizons because the music was so trite that it was hardly beyond the “Flatland” life I was leading. It was more of a hope that someday I could get away from my parents and live a life as exciting as musicians, and not at all like my parents’ lives.

Application of theories of celebrity to rock and roll and rhythm and blues

It is hard to imagine a musical celebrity without charisma, so part of the attraction has to be that. Again, the Frankfurt theory about social control doesn’t apply for the same reasons I gave in my section on James Dean. Even if we take the rhythm and blues scene into the sixties, with the exception of the early 60s, most rock and rhythm and blues supported the anti-war civil rights movement. It was not a distraction or an escape.

My reservations about Morin’s and Klapp’s theories apply for the same reasons as they do for movie stars. Again, mass media was crucial to my attachment to rock and roll and rhythm and blues. The music was on the radio, on TV, in live concerts, and in the movies. All these media sources saw lots of money to be made. Furthermore, as in my commentary on James Dean, I listened to this music when I was between 10-20 years old, which is prime time for rebellion. Had I been forty years old and digging this movement, we would need a different explanation.

Type of fan attachment for rock and roll and rhythm and blues

What kind of fan attachment did I have to rock and roll and rhythm and blues?

It was deeper than my movie attachment (see my article My Love Affair with Rhythm and Blues). I didn’t just listen to the music. I sang along and I also sang into a tape recorder. I really worked at imitating my favorites – Buddy Holly, Elvis, the Drifters. Going into my room and closing the door, I would go “Up on the Roof” just like the Drifters invited me to do. These musicians were my gods and goddesses. I memorized their songs, showed up at their concerts, bought their records, found out about their lives, rooted for them to have hits and cried when they faded or died. I cried when Sam Cooke died and I cried when Elvis made his comeback. I see my attachment as a combination of self-identification and imitation. I bought the same kind of clothes they had and styled my hair like theirs. As I said in my Rhythm and Blues article, they were my gods and goddesses. Given how much I still listen to their music, they still are.

Idol 3 Sports: Mickey Mantle

Being a participant deepens attachment as a fan

As I hope I demonstrated in this last section, the degree to which we become involved with a single or multiple celebrities also depends on our own willingness to move beyond being a spectator and become a participant. My relationship with a movie star celebrity will intensity if I act myself. In music, if I play an instrument myself, I will feel more involved with the musician. In the case of sports, I played baseball (hardball) myself. As a fan, I started to follow the Yankees at about the same time my father and I used to play catch and hit the ball around. In both cases, I was about 7 years old and the time was 1955.

Like many New York kids at that time, the ultimate choices of idols came from the New York teams – Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle or Duke Snider. One of the reasons I think I loved Mickey Mantle was that his plate appearances were so dramatic – he either hit tape measure home runs or struck out or he walked. There was always controversy around him because many New Yorkers insisted he could never replace Joe DiMaggio. Mantle was often booed by the fans. Because he was a country boy from Oklahoma, he was not articulate with the press which made things worse.

As I was playing stick ball in the streets and hard ball in the sandlots, I used to imitate Mickey, copying his batting stance. I became a good drag bunter, in part from knowing and copying Mickey. I mostly used to try to hit home-runs and was proud that I could do this, even though I was not especially big physically. From the time I was seven to eleven years of age, I played shortstop. But once the batters were strong enough to hit the ball to the outfield, I switched positions. I was naturally drawn to centerfield, because, as in shortstop, you can see the big picture. I was also suited to the position because I was fast, graceful and had a good arm. But there was part of me who wanted to play center because that was Mickey’s position.

In my sandlot career, there were two or three guys in the lineup who were better hitters than I was and they hit more home-runs, so typically I batted fifth. I liked this position because I was a better hitter with runners on base and I liked being in a position to drive in runs. But when I played with other teams who weren’t as good, I batted third or even fourth. It sent shivers up my spine to see the line-up card with me batting third or fourth and playing center field. That was Mickey’s position in the batting order. A couple of times we had games in upper middle-class neighborhoods where the fields actually had announcers telling the fans the lineups. “Batting fourth, playing centerfield, Bruce Lerro”. I imagined I was at Yankee stadium and Bob Scheffing would announce the batting order. “Battling fourth, playing centerfield, Number 7, Mickey Mantle”, and the crowd would roar. No crowd roared for me, but my imagination did the rest.

When I was growing up there was no free agency for the players. That meant that being traded from one team to another was rare. Whoever your favorite player was, you could count on them always being there, barring injuries. Good players could last between 10 and 20 years. Mickey’s career lasted about 17 years, which was the same duration as my interest in baseball as both a fan and a player. Both ended in 1969. To give you a sense of how the fans felt about Mickey, I shall share a link with you. About 15 minutes in, you will see Mel Allen’s introduction along with a standing ovation which lasted at least seven minutes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2HnZi0Ad-Y

Sports celebrities were loved and hated by their fans and in New York the fans did not save their boos only for the opposing team. When I would go to ballgames, I would boo some of the home team players. I would wait with my friends for the players after the game to see them come out. Two of my friends and I snooped around a hotel that we heard Mantle and Roger Maris were staying at in Queens. I knew the statistics of the players, which was good evidence for arguments about who was the best player. I watched the full ball games about three times a week and I would go in person to games, maybe once a month for six months. I cried when the Yankees lost the world series to the Braves in 1957 and celebrated when they won in 1958.

Fortunately for me, I never got so carried away as some fans do. I remember in the 1993 World Series when Mitch Williams gave up a three-run homer to Joe Carter to end the series. He received numerous death threats from Philadelphia fans. I think that actually playing the game as a participant, and being relatively successful helped to ground me, but not completely.

Application of theories of celebrity to sports

Unlike movie stars and musicians, it is possible not to be charismatic and be a professional baseball player. Charisma is not a major factor that draws fans to a particular player. In addition, the Frankfurt School theory about celebrities being a form of social control for capitalists definitely has truth in relation to sports. Noam Chomsky famously puzzled over the fact that so many people in the United States were ignorant about politics, social class, and economics. Yet these same people could make very sophisticated comments about their favorite teams’ strategies and tactics, in addition to knowing the player’s batting average, runs batted in and homeruns. Sports is definitely a diversion. Edgar Morin’s argument about the stars being a compensation for fan’s deadened lives also has merit. Many Americans are way out of physical shape, and a good case can be made that they are living vicariously through the well-trained magnificent specimens of working-class men. Again, the power of the mass media capitalists has done a great deal to spread sports. Like music, sports is on TV, the radio and in stadiums regularly. Sports’ stars for the most part do not fit into Klapp’s theory of social type. Sports writers attempt to categories players into “Good Joes”, “Rebels”, and other types in the hopes that this will make their fans read their articles. But the best fans know that the personalities of the players cannot be reduced to cartoon characters.

Type of fan attachment to sports

The level of my fan attachment was deeper in sports than it was with either music or movie stars. One reason for this was that I became relatively good for a non-professional participant. This deepened my appreciation of the players. Also, sports are much more continuous and intense than the movie or music industry. The timing in the fields of both the hit movies or hit songs and who sings them is unpredictable. But in baseball you have predictability. You have six months straight to follow a team and your favorite players. In addition to the self-identification and the mimicking, there were elements of projection in my involvement as a fan.

I played hardball till I was 20 years old, which was pretty old to play if you aren’t going to do it professionally. Partly I did this because it was the only thing I was relatively good at, but partly because I was stupidly waiting to be discovered by scouts. Some adult should have read me the riot act and insisted that I cultivate other skills for future work. For whatever reasons, no one did. I don’t know if that would have mattered. I doubt I would have listened to anyone anyway. The following is an example of how being enthralled with sports and celebrities sidetracked my development as a worker.

My last baseball game was at a softball game in 1998. It was a game between the faculty and the students at a liberal arts school where I had been teaching for seven years. We won the game 15-7. I hit a three-run home run and two three -run triples, driving in nine runs. The fact that I can still remember these numbers 23 years later says a great deal about how, for better and for worse, baseball has swept me away. I wasn’t star-struck, but I was pretty close. Below is a picture of me hitting a three-run triple in first inning of that game.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to give the reader an experiential sense of what it was like for me to be a celebrity fan in three different genres of movie stardom, music stardom and sports stardom. I began the article by arguing how celebrities are unique to industrial capitalist countries. I then make a key distinction between people who are famous and people who are celebrities. I then proceeded to describe my experience with three stars: James Dean (movies), Jerry Lee Lewis (music), and Mickey Mantle (sports). For each genre I described:

- which theory of celebrity works best;

- which of the four kinds of audience participant I was.

I have made the argument that, for me, sports were the most powerful form of celebrity and why. But I also justify it by claiming that the consistency with which sports is played throughout the year makes it likely the most intense form of socialization for the population of the United States, should they choose to become a fan.

• First published in Socialist Planning Beyond Capitalism

No comments:

Post a Comment