The meaning of net zero and how to get it right

Nature Climate Change (2021)

Abstract

The concept of net-zero carbon emissions has emerged from physical climate science. However, it is operationalized through social, political and economic systems. We identify seven attributes of net zero, which are important to make it a successful framework for climate action. The seven attributes highlight the urgency of emission reductions, which need to be front-loaded, and of coverage of all emission sources, including currently difficult ones. The attributes emphasize the need for social and environmental integrity. This means carbon dioxide removals should be used cautiously and the use of carbon offsets should be regulated effectively. Net zero must be aligned with broader sustainable development objectives, which implies an equitable net-zero transition, socio-ecological sustainability and the pursuit of broad economic opportunities.

Main

Climate policy has a new focus: net-zero emissions. Historically, climate ambition has either been formulated as a stabilized level of atmospheric concentrations (for example, in the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) or as a percentage emissions reduction target (for example, in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol). Now climate ambition is increasingly expressed as a specific target date for reaching net-zero emissions, typically linked to the peak temperature goals of the Paris Agreement. Almost two-thirds of global emissions and a slightly higher share of global gross domestic product are already covered by net-zero targets1.

Net zero is intrinsically a scientific concept. If the objective is to keep the rise in global average temperatures within certain limits, physics implies that there is a finite budget of carbon dioxide that is allowed into the atmosphere, alongside other greenhouse gases. Beyond this budget, any further release must be balanced by removal into sinks.

The acceptable temperature rise is a societal choice, but one informed by climate science. Under the Paris Agreement, 197 countries have agreed to limit global warming to well below 2 °C and make efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C. Meeting the 1.5 °C goal with 50% probability translates into a remaining carbon budget of 400–800 GtCO2. Staying within this carbon budget requires CO2 emissions to peak before 2030 and fall to net zero by around 20502.

However, net zero is much more than a scientific concept or a technically determined target. It is also a frame of reference through which global action against climate change can be (and is increasingly) structured and understood.

Achieving net zero requires operationalization in varied social, political and economic spheres. There are numerous ethical judgements, social concerns, political interests, fairness dimensions, economic considerations and technology transitions that need to be navigated, and several political, economic, legal and behavioural pitfalls that could derail a successful implementation of net zero.

Getting net zero, the frame of reference, right is therefore essential. This Perspective recapitulates the scientific logic behind net zero and sets out the attributes we believe are important to turn it into a successful framework for climate action across countries.

The seven attributes complement an emerging set of operational principles and criteria, which have been put forward to govern specific net-zero decisions, such as country-level target setting3, the design of institution-level net-zero commitments (https://racetozero.unfccc.int/, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/ and ref. 4), the management and disclosure of climate risks5, and the use of carbon offsets6.

Net zero as a scientific concept

Net zero is just a number, begging the question ‘net zero what?’ For CO2, the answer emerged in the late 2000s from understanding what it would take to halt the increase in global average surface temperature due to CO2 emissions. A series of papers noted the longevity of the impact of fossil carbon emissions7,8,9 and the monotonic, near-linear (so far) relationship between cumulative net anthropogenic CO2 emissions and CO2-induced surface warming10,11,12,13. The corollary of this result is that CO2-induced warming halts when net anthropogenic CO2 emissions halt (that is, CO2 emissions reach net zero), with the level of warming determined by cumulative net emissions to that point.

Unless net CO2 emissions then go below zero, CO2-induced surface warming is expected to remain elevated at this level for decades to centuries14. This occurs because for, and only for, time intervals of 40–200 years, the rate of atmospheric CO2 uptake by the deep oceans (acting to reduce warming) occurs at a rate similar to the thermal adjustment of the deep oceans to raised atmospheric CO2 (acting to increase warming)9,15.

Total anthropogenic warming is a function not only of CO2, but also of a range of other greenhouse gases and forcings16. These have different efficacies and lifetimes of influence on climate, generally shorter-lived than that of CO2. Non-CO2 anthropogenic warming is therefore better determined not by cumulative emissions, but by the present-day emission rate plus a small correction for the long-term climate response to the average non-CO2 forcing over a multi-decade to century time interval17. Hence, the IPCC statement “reaching and sustaining net-zero global anthropogenic CO2 emissions and declining net non-CO2 radiative forcing would halt anthropogenic global warming on multi-decadal timescales2.”

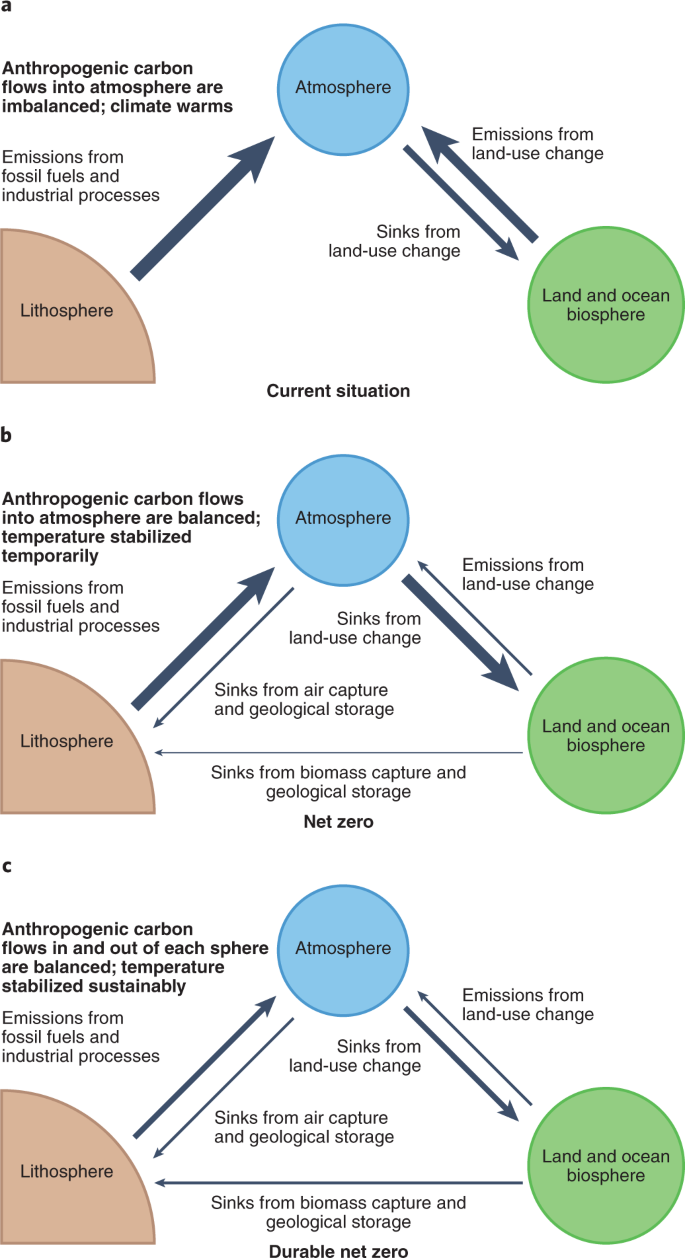

These observations have an immediate policy implication: it makes little sense to apply the net-zero concept on timescales shorter than decades. Achieving net zero through an unsustainable combination of fossil-fuel emissions and short-term removals is ultimately pointless. Carbon emissions and removals must balance over multi-decadal timescales (Fig. 1).

a–c, Current anthropogenic carbon flows to and from the atmosphere are not in equilibrium: emissions from fossil fuels, industrial processes and land-use change by far exceed the removal of carbon into land-use-related sinks (a)16. Net zero requires anthropogenic flows to and from the atmosphere to balance on aggregate. This necessitates a radical reduction in fossil-fuel- and land-use-related carbon emissions as well as an increase in geological and biological sinks (b). A durable net zero further recognizes that biological storage is limited in capacity and shorter-lived than geological storage. A durable net-zero state therefore requires that net anthropogenic flows to and from each sphere (not just the atmosphere) equal zero (c). Note that natural flows of carbon are not shown in this figure and involve a small net flow from the atmosphere to the biosphere when net zero is reached.

We must also accept that net-zero emissions may still be associated with some further very slow warming or cooling on longer timescales, and that the temperature implications of the net-zero concept when applied to non-CO2 climate drivers are less clear than they are for CO2 alone, depending on the specific mix of drivers18.

There are alternative interpretations of net zero. Sometimes, net zero is used simply to describe emissions trajectories consistent with 1.5 °C (https://sciencebasedtargets.org/). While a helpful shorthand, this obscures the fact that halting global warming, at whatever temperature level, requires net-zero CO2 emissions and declining non-CO2 radiative forcing.

Alternatively, net zero is often understood to mean net-zero CO2-equivalent emissions aggregated using the 100-year ‘global warming potential’ metric. This cannot be related unambiguously to any temperature outcome, but is generally seen as more ambitious, and hence preferable, than ‘just’ halting human-induced global warming19. It may, of course, be necessary to aim for a long-term decline in global temperature. If so, the above empirical relationship remains applicable to determine what needs to be net zero to deliver this more ambitious goal. However, as we see it, the concept of net zero emerged from our understanding of what it would take to achieve a temperature goal, not vice versa.

The importance of these differences in interpretation should not be overstated: the fact that net zero needs to apply to a state of balance that can be maintained over multiple decades, meeting additional environmental and social criteria, limits the scope for compensation among different climate drivers. It also limits the scope for compensatory exchanges between different carbon pools in the atmosphere, biosphere, oceans and lithosphere.

The adoption of net-zero targets

The carbon budgets calculated by scientists apply to the global atmosphere, rather than individual entities. To turn net zero into a useful frame of reference for decision-makers, the global carbon constraint needs to be translated into individual decarbonization pathways for nation states, sub-national entities, companies and other organizations.

Setting such entity-level targets and defining how they interact requires judgement. There are many ways in which the remaining carbon budget can be managed. Although there is a considerable literature on this subject18,20,21,22,23, in practice defining the scope, timing, fairness and relevance of entity-level net-zero targets has been left to individual emitters and self-regulated voluntary codes. This leaves open the question of how a diverse set of voluntary pledges adds up to national targets and national targets add up to the global carbon budget.

The Paris Agreement leaves it to its parties to define their own emissions pathways or nationally determined contributions to global net zero. There is no official yardstick against which the adequacy, ambition or fairness of nationally determined contributions is measured. Instead, the Paris Agreement relies on process. Regular stocktakes are intended to catalyse ambitious action and ensure that national emissions pathways will gradually converge to a global net-zero state consistent with the long-term temperature goals.

More than 120 countries have now pledged to reach net zero in some shape or form around mid-century, consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. They include China, the European Union and the United States, the world’s three largest greenhouse gas emitters.

Individual organizations are effectively accounted for in the carbon targets of the countries in which they operate, but many have made their own individual net-zero pledges. In doing so, they are guided by voluntary schemes, such as Cities Race to Zero, the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance and the Science-based Target Initiative, which encourage entities to bring down their emissions as fast as reasonably practicable and many of which are partners of the United Nations’ Race to Zero campaign (https://racetozero.unfccc.int/). Progress is measured and assessed by frameworks such as CDP (https://www.cdp.net/en) and the Transition Pathway Initiative (https://www.transitionpathwayinitiative.org/).

At the time of writing, more than 100 regional governments, 800 cities and 1,500 companies have adopted organizational net-zero targets, often considerably earlier than mid-century1. One in five corporations in the Forbes Global 2,000 list have set a voluntary net-zero target.

KEEP READING HERE

The meaning of net zero and how to get it right | Nature Climate Change

No comments:

Post a Comment