USSR 1922-1991, USA 1776-2025?

Thirty years ago today the Soviet Union came to an end. This is not an occasion for triumphalism. It is a warning.

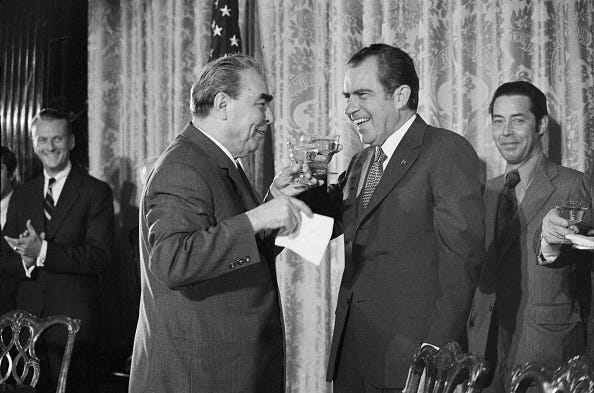

Stagnation, or the absence of a future, was the underlying Soviet problem. Stalinism had created temporary social mobility in the Soviet Union, if at the cost of millions of deaths and the creation of the largest prison system in the world. Leonid Brezhnev, who consolidated power in 1964 and held it until his death in 1982, inherited a mature system. He abandoned the promise that Soviet rule could bring harmony and freedom, and aimed for maintenance and nostalgia. He created a cult of the Second World War, an era of past greatness. Stalinism meant that peasants became workers; now what was on offer to second- or third-generation workers was the memory of Stalinism. Social mobility was difficult. The status quo seemed inevitable and eternal.

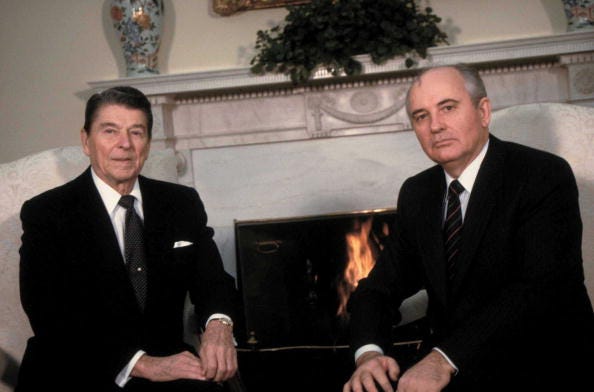

Everything was forever until it was no more -- as Alexei Yurchak titled his book about the last Soviet generation. Mikhail Gorbachev, the youthful Soviet leader who came to power in 1985, had ideas about revival. He was trying in 1990 and 1991 to breathe life into a federation. His idea was that the Soviet state, established on new federal lines, would be easier to control than a recalcitrant and decadent communist party. He fell from power on the issue of how much power should remain in the center, and how much devolved to the republics. Boris Yeltsin, his rival, was pushing for more authority for the Russian republic. Gorbachev was hoping that his new union treaty would settle the question. The Soviet hardliners who attempted a coup in August 1991 thought Gorbachev had gone too far. Their failed attempt sidelined Gorbachev and opened the field for Yeltsin to pull Russia out of the USSR. On this date in 1991, Yeltsin, along with the leaders of Belarus and Ukraine, formally dissolved the Soviet Union.

Under Vladimir Putin, today's official Russian version of these events is that the end of the Soviet Union was a western plot. In fact Western leaders, supporters of Gorbachev, was surprised and dismayed. The West had much to do with collapse of communism in Europe, less through its foreign and military policies, than by its example. Western domestic policies had succeeded in providing many people with a sense of the future. A combination of elections, markets, the welfare state, and unions allowed both the United States and western Europe to provide not just rising standards of living but also a belief that members of coming generations might do something new and interesting. This story is told on the European side in Tony Judt's outstanding history Postwar. In the United States, this social mobility was known as the "American Dream."

Western social mobility was most clearly visible from Soviet Union's outer empire, eastern Europe. East European communist regimes were encouraged to follow the Soviet model and to focus on satisfying the consumer demands of the working class. But once communism was premised on an inferior version of the Western lifestyle, it could not defend itself against comparisons to the West. The proximity of western Europe and the attractiveness of American culture made it obvious that people could enjoy both greater freedom and greater prosperity than was on offer in eastern Europe. When Gorbachev came to power, he cast the east European regimes adrift, assigning them to find their own ways to socialism. The roundtables and elections that followed in Poland and elsewhere brought an end to the satellite regimes in 1989. The end of the outer empire led to the end of the empire itself. It created a sense of possibility and a model for change which would be seized upon in the USSR itself in 1991.

Once American leaders and thinkers got over their surprise at this turn of events, they tended to interpret them as an affirmation of contemporary policies that were designed to break unions and undo the welfare state. That was a mistake. Given further authority by the by the end of communism, American politicians of the 1980s prepared the way for an American crack-up, the one that we are experiencing now.

In a certain way, our choices since the 1980s recall the Brezhnev era. Reagan and Brezhnev, for example, were of similar minds about free labor unions. In 1980, an east European working class opened the one meaningful window of freedom in the communist world. That summer, Polish workers established a labor union, Solidarity, that bargained for freedom of expression, as well as for economic goals. Legal in communist Poland for more than a year, its existence challenged the way Soviet-style systems were supposed to work. Bogged down by war in Afghanistan, the USSR could not afford to invade its Polish neighbor, as it had done in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. Brezhnev instead pressured the communist regime in Poland to declare martial law itself, which it eventually did. Solidarity was broken and criminalized in December 1981.

This was four months after the Reagan administration began its own crackdown on unions, by firing striking air traffic controllers. That set the tone for a change in attitudes and policies that led to the humbling of the American labor movement. In the early 1980s, about 20% of American workers were members of unions. Today the figure is more like ten percent. That, in turn, is a basic cause of decreased American social mobility.

Brezhnev died in 1982, but his spirit lived on. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was essentially plagiarizing Brezhnev when she claimed that "there is no alternative." Thatcher meant capitalism, of course, rather than Soviet rule. But the argument, and the basic consequence, is the same. If there are no alternatives, then the role of the citizen is reduced to zero. Experts will decide what is best for us, and will explain to us why this or that disaster was a necessary element of this best of all possible worlds.

After the end of the USSR, Thatcher's idea that there were "no alternatives" to capitalism achieved a broad consensus. This dulled our minds to the future, and made capitalism itself more doctrinaire and less tolerable. We plagiarized communism's dead philosophy. Thatcher and Reagan pulled the grungy idea of economic determinism from the dustbin of history. Naturally, our version of economic determinism was different than the Soviet one: not that state planning would automatically bring socialism, as Soviet leaders had maintained, but that capitalism would automatically bring democracy. But the basic error was the same. We were wrong, just as the Soviets had been.

It was not in fact true that capitalism would bring democracy: consider China. The twenty-first century has been quite good for capitalism, but quite bad for democracy. More fundamentally, determinism about freedom cannot be true in principle. Democracy means that people are free to rule themselves. To accept that freedom can be delivered mechanically by a larger economic process is not only to misunderstand freedom but also to render it impossible. Anyone who expects freedom to be delivered by some external force will get the opposite.

And so, in our minds and in our institutions, we did away with the model that seemed attractive to people suffering under communism. Having weakened both unions and the welfare state, we brought our own era of stagnation. The American standard of living today is comparable to that of 1981, when Reagan and Brezhnev cracked down on unions. The welfare state has been replaced, in some measure, by a carceral state: it is we who now have the largest prison system in the world. Social immobility is a central feature of American life, as it was of Soviet life. The attendant anger and frustration generate political alternatives to democracy.

We too have chosen determinism over freedom and cut off the future. We too have lost a war in Afghanistan during an age of stagnation. We have had a failed coup attempt, and are now awaiting a second. We too have our problems in regulating relations between the center and the federal units. Some of our states have passed legislation that compromises elections, in preparation for a full subversion of democracy in 2024. Should a president be installed in 2025 after losing an election, the United States could fall apart.

History does not repeat. It does, however, give us a chance to rethink. All regimes come to an end, and rarely is this understood as it is happening. Few of us expected the USSR to disintegrate, but it did. Few of us might expect the USA to disintegrate, but it could. The scenario does not seem so distant to me now.

The point is not that the U.S. is just like the U.S.S.R., but that we have missed some important resemblances. Proclaiming our superiority and our indignation at comparisons is not the way forward. Nationalist pathos just makes things worse. Exceptionalism and triumphalism are not the mark of success but of vulnerability. Whether or not a stagnating system collapses depends, at least in some measure, on self-awareness. History can help us become more self-aware.

Looking back, we can see how the West won the cold war: a combination of elections, markets, the welfare state, and labor unions that allowed social mobility and a sense of the future. We can also see that we have made a mistake, since the 1980s, in throwing away most of our advantages, and weakening a system that once looked formidable and attractive. It would be best to notice this while we still have some time to do something about it.

When we remember the end of the Soviet Union, we should not be congratulating ourselves. We should be asking ourselves what we have done wrong these last thirty years, and thinking about how to end our own stagnation. We should be preparing for the crisis looming in 2025. After all, there are always alternatives, some better, some worse.

No comments:

Post a Comment