[Editorial] Chun Doo-hwan: Gone but never to be forgiven

Efforts to rehabilitate Chun must not be tolerated

Rain drizzles on the Mangwol ceremony, the burial site of many of those killed during the 1980 massacre, on Tuesday, the day Chun Doo-hwan died. (Kim Hye-yun/The Hankyoreh)

Efforts to rehabilitate Chun must not be tolerated

Rain drizzles on the Mangwol ceremony, the burial site of many of those killed during the 1980 massacre, on Tuesday, the day Chun Doo-hwan died. (Kim Hye-yun/The Hankyoreh)

Posted on : Nov.24,2021 17:25 KST Modified on : Nov.24,2021 17:25 KST

Chun Doo-hwan, who was responsible for the massacre in Gwangju in May 1980, died at his home in the Yeonhui neighborhood of Seoul on Nov. 23, unapologetic and unremorseful until the very end. While it’s our practice and inclination to be somewhat magnanimous to the deceased, no sympathy can be felt for the death of the ringleader of a rebellion who seized power through a coup and butchered Koreans who tried to resist.

Chun’s junta, which took power in a coup on Dec. 12, 1979, smashed the “spring of democratization” in 1980 and crushed a movement for democracy in Gwangju that May with military force. Chun slaughtered innocent civilians to satisfy his lust for power. He committed crimes that history will never erase. Even after seizing power, he persisted in his pitiless tyranny, violating democracy and human rights and inflicting grievous pain on the public. He also kept cozy ties with Korea’s chaebol — family-owned conglomerates — and pocketed huge bribes from them.

Chun had several opportunities to repent before his death. But he continued making audacious excuses for his crimes and indulging in self-justification until his death. Not once did he exhibit the slightest trace of remorse.

When he was put on trial for sedition and for his role in the Gwangju massacre during the presidency of Kim Young-sam, he said that the Gwangju democracy movement had been “a scheme hatched by leftist groups” and he described the movement as an “insurrection” in his memoir, which was published in 2017. Chun slandered late Catholic priest Cho Pius — who testified to seeing government troops shooting at protesters from helicopters during the uprising — as being “Satan in disguise” and “a shameless liar.”

Chun is often compared to Roh Tae-woo, who passed away a month ago. But at least Roh offered an apology through his surviving family members, who reported that he’d “asked for forgiveness for his mistakes.”

Another point of contrast with Roh is that Chun didn’t pay the restitution he owed the government for 25 years. The prosecutors managed to seize 124.9 billion won (US$105.01 million) of his assets, but Chun still owed almost just as much — 95.6 billion won (US$80 million). When the prosecutors placed Chun’s home in Yeonhui neighborhood up for auction in an attempt to collect the rest of the money, Chun’s family members brazenly sued to stop the auction.

Chun’s wife, Lee Soon-ja, has earned her own share of public scorn. She claimed in her autobiography in 2017 that Chun’s responsibility for the massacre in Gwangju was a “political distortion of history” and made the wild claim prior to attending a court hearing in 2019 that “my husband is the father of democracy in the Republic of Korea.”

Throughout his life and until its very end, Chun committed crimes against the Korean people and history itself. It would be extremely inappropriate for government officials or politicians to convey their condolences or attend his wake, not to mention holding a state funeral for the man.

It’s regrettable that the Blue House nevertheless said on Tuesday, “We express our condolences for Chun Doo-hwan and express our sympathy to his bereaved family.” Officials added that there were “no plans to send flowers or pay respects at his wake” given Chun’s failure to offer “a sincere apology.” Even so, we consider the Blue House’s comments unfit for a butcher like Chun. The people who deserve our sympathy are the victims of the massacre in Gwangju and their bereaved family members, who never received a single word of apology from Chun.

There have recently been some regressive efforts to rehabilitate Chun. That apparently prompted Yoon Seok-youl, presidential candidate for the People Power Party (PPP), to remark that “many people say that Chun Doo-hwan was really good at politics aside from the coup and the events of May 1980” — a remark for which Yoon eventually apologized.

We must be cautious and alert about such efforts and must not tolerate them. Undeniably, the democratization of Korean society has continued since the protests of 1987 while surmounting a number of obstacles.

The PPP decided not to release an official statement on Chun’s death. Its cowardly silence is presumably motivated by concern for public opinion and its own hardcore supporters on the far right. Political groups that don’t fear history are no more than special interest groups representing their supporters. The essence of a conservative party is prioritizing public safety above all else. With its current attitude, the PPP won’t be able to break out of the confines of a reactionary party.

With the consecutive deaths of Roh Tae-woo and Chun Doo-hwan, the era of military dictatorship in Korea has at last receded into the past. In effect, Korea has turned a page in its history.

Even so, we must keep trying to learn the full truth about the massacre in Gwangju. That includes determining who ordered the martial law troops to fire the first shots at Gwangju Station at 10:30 pm on May 20, 1980, and to fire the first volleys in front of South Jeolla Provincial Office at 1 pm on May 21, as well as identifying the missing people whose fate remains unknown and finding and recovering the bodies of the victims.

Our failure to uncover more about what happened on that day 41 years ago should have us hang our heads in compunction before Gwangju’s victims, before those like Park Jong-chul and Lee Han-yeol who died in the struggle for democracy, and before history itself. In the tribunal of history, there is no statute of limitations.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Chun Doo-hwan, who was responsible for the massacre in Gwangju in May 1980, died at his home in the Yeonhui neighborhood of Seoul on Nov. 23, unapologetic and unremorseful until the very end. While it’s our practice and inclination to be somewhat magnanimous to the deceased, no sympathy can be felt for the death of the ringleader of a rebellion who seized power through a coup and butchered Koreans who tried to resist.

Chun’s junta, which took power in a coup on Dec. 12, 1979, smashed the “spring of democratization” in 1980 and crushed a movement for democracy in Gwangju that May with military force. Chun slaughtered innocent civilians to satisfy his lust for power. He committed crimes that history will never erase. Even after seizing power, he persisted in his pitiless tyranny, violating democracy and human rights and inflicting grievous pain on the public. He also kept cozy ties with Korea’s chaebol — family-owned conglomerates — and pocketed huge bribes from them.

Chun had several opportunities to repent before his death. But he continued making audacious excuses for his crimes and indulging in self-justification until his death. Not once did he exhibit the slightest trace of remorse.

When he was put on trial for sedition and for his role in the Gwangju massacre during the presidency of Kim Young-sam, he said that the Gwangju democracy movement had been “a scheme hatched by leftist groups” and he described the movement as an “insurrection” in his memoir, which was published in 2017. Chun slandered late Catholic priest Cho Pius — who testified to seeing government troops shooting at protesters from helicopters during the uprising — as being “Satan in disguise” and “a shameless liar.”

Chun is often compared to Roh Tae-woo, who passed away a month ago. But at least Roh offered an apology through his surviving family members, who reported that he’d “asked for forgiveness for his mistakes.”

Another point of contrast with Roh is that Chun didn’t pay the restitution he owed the government for 25 years. The prosecutors managed to seize 124.9 billion won (US$105.01 million) of his assets, but Chun still owed almost just as much — 95.6 billion won (US$80 million). When the prosecutors placed Chun’s home in Yeonhui neighborhood up for auction in an attempt to collect the rest of the money, Chun’s family members brazenly sued to stop the auction.

Chun’s wife, Lee Soon-ja, has earned her own share of public scorn. She claimed in her autobiography in 2017 that Chun’s responsibility for the massacre in Gwangju was a “political distortion of history” and made the wild claim prior to attending a court hearing in 2019 that “my husband is the father of democracy in the Republic of Korea.”

Throughout his life and until its very end, Chun committed crimes against the Korean people and history itself. It would be extremely inappropriate for government officials or politicians to convey their condolences or attend his wake, not to mention holding a state funeral for the man.

It’s regrettable that the Blue House nevertheless said on Tuesday, “We express our condolences for Chun Doo-hwan and express our sympathy to his bereaved family.” Officials added that there were “no plans to send flowers or pay respects at his wake” given Chun’s failure to offer “a sincere apology.” Even so, we consider the Blue House’s comments unfit for a butcher like Chun. The people who deserve our sympathy are the victims of the massacre in Gwangju and their bereaved family members, who never received a single word of apology from Chun.

There have recently been some regressive efforts to rehabilitate Chun. That apparently prompted Yoon Seok-youl, presidential candidate for the People Power Party (PPP), to remark that “many people say that Chun Doo-hwan was really good at politics aside from the coup and the events of May 1980” — a remark for which Yoon eventually apologized.

We must be cautious and alert about such efforts and must not tolerate them. Undeniably, the democratization of Korean society has continued since the protests of 1987 while surmounting a number of obstacles.

The PPP decided not to release an official statement on Chun’s death. Its cowardly silence is presumably motivated by concern for public opinion and its own hardcore supporters on the far right. Political groups that don’t fear history are no more than special interest groups representing their supporters. The essence of a conservative party is prioritizing public safety above all else. With its current attitude, the PPP won’t be able to break out of the confines of a reactionary party.

With the consecutive deaths of Roh Tae-woo and Chun Doo-hwan, the era of military dictatorship in Korea has at last receded into the past. In effect, Korea has turned a page in its history.

Even so, we must keep trying to learn the full truth about the massacre in Gwangju. That includes determining who ordered the martial law troops to fire the first shots at Gwangju Station at 10:30 pm on May 20, 1980, and to fire the first volleys in front of South Jeolla Provincial Office at 1 pm on May 21, as well as identifying the missing people whose fate remains unknown and finding and recovering the bodies of the victims.

Our failure to uncover more about what happened on that day 41 years ago should have us hang our heads in compunction before Gwangju’s victims, before those like Park Jong-chul and Lee Han-yeol who died in the struggle for democracy, and before history itself. In the tribunal of history, there is no statute of limitations.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

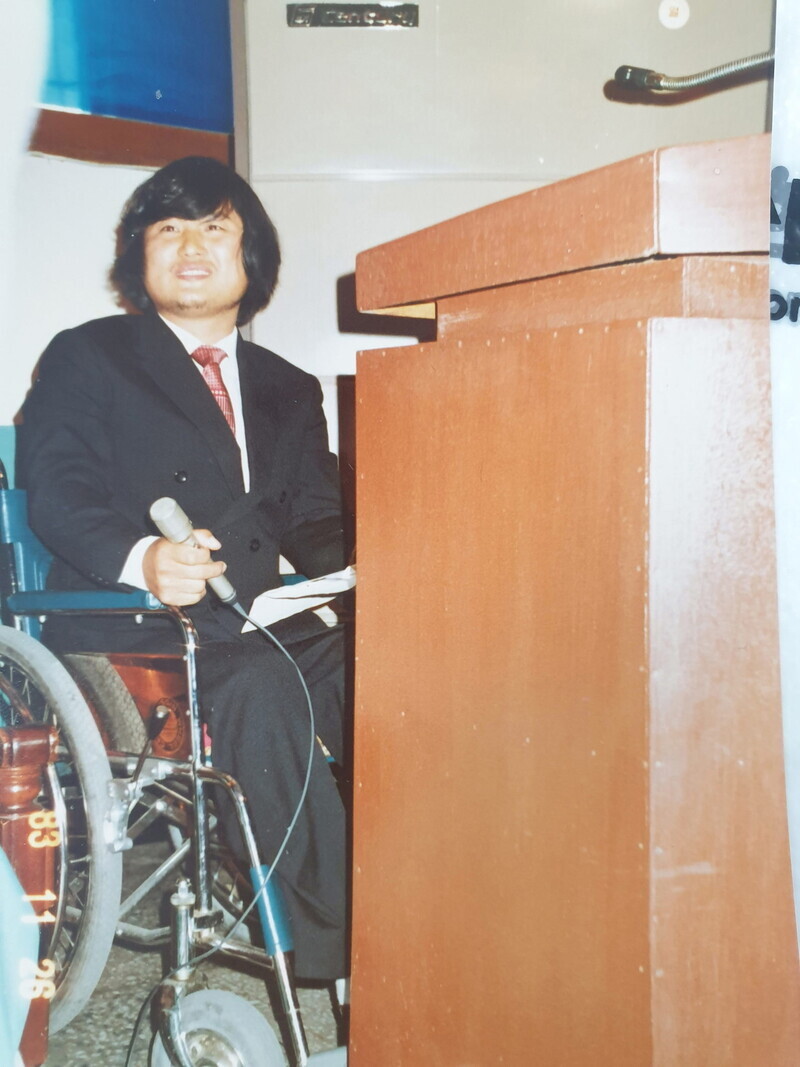

Lee Gwang-yeong dedicated his life to uncovering the truth of the Gwangju Uprising and its brutal suppression, and took the witness stand in 2019 in the case against Chun for defaming the dead

Lee Gwang-yeong, pictured here, testified to witnessing a military helicopter opening fire on civilians during the democratic popular uprising in Gwangju, May 1980. (Hankyoreh archive photo)

Posted on : Nov.25,2021

Sighs of disbelief could be heard among those gathered at the wake of Lee Gwang-yeong, 68, in the Buk District of Gwangju on Wednesday.

“He’d fought his whole life against Chun Doo-hwan, and now he’s left us. God only knows how hard that was,” one of the visitors said.

Lee’s body had been found the day before in a reservoir in Gangjin County, South Jeolla Province, the place where he’d been born. Before his death, he wrote a short note on a piece of paper in his home in Iksan, North Jeolla Province. Considering that Lee drove himself to Gangjin, the police concluded that he had died by suicide.

Lee had been paralyzed from the waist down — the result of being shot in the spine by government troops sent to suppress the Gwangju Uprising in 1980.

“The last time we spoke on the phone was a week ago, so I was really shocked to hear the news yesterday. He’d always been in a lot of physical and mental pain, and then this,” said Lee Ji-hyeon, inaugural chairperson of an association for people injured in the Gwangju massacre.

“My brother had been in so much pain [recently] that he’d become dependent on painkillers,” said Lee Gwang-seong, 61-year-old younger brother to Gwang-yeong. “I think he went down this path because of his personality — he never wanted to be a burden on others.”

It’s presumed that Lee Gwang-yeong passed away around midnight on Tuesday. After Chun Doo-hwan died at 9 am that very morning, survivors of the Gwangju massacre drew attention to the tragic fate connecting the two.

Lee, then a Buddhist monk who went by Jingak, was on his way to Jeungsim Temple, near Gwangju, on May 19, 1980, when he took part in the uprising. He was helping transport injured people to the hospital on May 21 when he was struck in the spine by a bullet fired by the martial law troops.

Lee Gwang-yeong emceed the wedding of Lee Ji-hyeon, the inaugural president of an association of those injured during the Gwangju Uprising, in 1983. (provided by Lee Ji-hyeon)

During his hospital stay, Lee returned to secular life and started a family. He ran a comic book shop and supplied food to schools.

Lee played an active role in bringing to light the truth of the Gwangju Uprising and the slaughter of protesters. He helped set up the association for the injured in 1982 and testified in the Gwangju hearings at the National Assembly in 1988.

Along with late Catholic priest Rev. Cho Pius, Lee was one of the major figures who testified that martial law troops had fired on protesters from helicopters during the massacre. He was the first witness to testify in Chun’s first trial on charges of defaming the dead in May 2019.

“I was riding in a military jeep around 2 pm on May 21, 1980, when I witnessed helicopter gunfire while we were passing the roundabout at the Wolsan neighborhood in the Nam District of Gwangju,” he said.

Kang Seong-won, 59, one of the founding members of the association for the injured, had been close to Lee over the years. “He threw himself into the cause of uncovering the truth of the massacre and of bringing democracy [to Korea]. It’s so unfair to think he left us because he couldn’t bear the pain while Chun got to pass so peacefully.”

Almost every year, more massacre survivors end their lives, a troubling indication of the physical pain and psychological trauma they have suffered. Chung Byeong-gyun, who had been living alone, was found dead in September 2020.

According to a paper published in June by Kim Myeong-hee, a professor of sociology at Gyeongsang National University, 46 massacre survivors died by suicide between 1980 and 2019.

By By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

“It tears me up inside”: Mother of teen gone missing in Gwangju massacre reflects on death of Chun Doo-hwan

The city of Gwangju has recognized 84 people as having gone missing during the events of May 1980 in Gwangju

Kim Jin-deok, whose son went missing during the Gwangju Uprising. (provided by Kim Jin-deok)

Posted on : Nov.25,2021

“My only wish is to find even a sliver of my son’s bones before I die… It tears me up inside to think that that man, Chun Doo-hwan, could just croak on us like that without so much as a single word.”

Kim Jin-deok, 77, who lives in Goheung County, South Jeolla Province, sighed with exasperation during a phone conversation with the Hankyoreh on Wednesday.

Kim’s son, Im Ok-hwan, set out from the temple where he’d been staying with friends to return to his home in Goheung in May 1980, while the Gwangju Uprising and its bloody suppression was underway. Im, who was a 17-year-old student in his second year of high school at the time, was never heard from again.

“After hearing about the trouble in Gwangju in May of 1980, I would speak on the phone with Ok-hwan every day. On the evening of May 19, Ok-hwan said to me, ‘Mom, I’m fine — don’t worry about me.’ That was our last phone call,” she recalled.

No longer able to reach her son on the phone, Kim headed to Gwangju on May 22. The bus only took her as far as Hwasun County, meaning she had to walk the rest of the way.

When she reached the temple where Im had been staying, Kim was told her son had left on May 21, apparently headed home. Upon hearing that, Kim collapsed on the spot.

Kim roamed through the hill behind Chosun University, the direction her son would have been heading, but she couldn’t find any traces of him. She walked around Gwangju until her feet were blistered, stopping by Chonnam National University Hospital and Chosun University Hospital, but her son was nowhere to be seen.

Assuming that Im was dead, the family prepared burial garments for him and returned to Gwangju on June 2. Neighbors joined the family in searching for him. They visited the Sangmugwan army gymnasium near the old South Jeolla Provincial Office where the bodies of the dead had been stored, but by the time they arrived, the bodies had already been moved elsewhere.

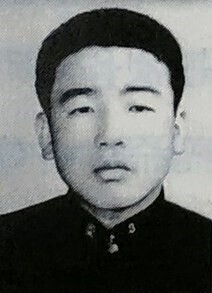

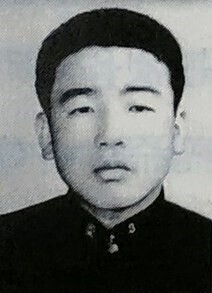

Im Ok-hwan, who went missing during the Gwangju Uprising in May of 1980

On the afternoon that Im went missing, the 872 enlisted soldiers and officers in the 7th Airborne Brigade, which had been stationed at Chosun University, moved across the hill behind the university to Neoritjae, a hill on the boundary between Gwangju and Hwasun. That overlapped with the route presumably taken by Im as he headed toward Hwasun on foot.

Kim says that all she wants is to find her son’s remains and bury them in a sunny spot. “My husband often laments that he probably won’t even find Ok-hwan’s bones before he dies. It makes me furious to think that powerless people like us are living with such pain while Chun Doo-hwan gets to die in comfort.”

The city of Gwangju recognized a total of 84 people as having disappeared during the Gwangju massacre. Six of them were identified when the bodies of victims were moved to a different cemetery in 2001, but the whereabouts of the other 78 remain unknown. For those who went missing without friends or family, hardly any information has yet to be ucovered.

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

The city of Gwangju has recognized 84 people as having gone missing during the events of May 1980 in Gwangju

Kim Jin-deok, whose son went missing during the Gwangju Uprising. (provided by Kim Jin-deok)

Posted on : Nov.25,2021

“My only wish is to find even a sliver of my son’s bones before I die… It tears me up inside to think that that man, Chun Doo-hwan, could just croak on us like that without so much as a single word.”

Kim Jin-deok, 77, who lives in Goheung County, South Jeolla Province, sighed with exasperation during a phone conversation with the Hankyoreh on Wednesday.

Kim’s son, Im Ok-hwan, set out from the temple where he’d been staying with friends to return to his home in Goheung in May 1980, while the Gwangju Uprising and its bloody suppression was underway. Im, who was a 17-year-old student in his second year of high school at the time, was never heard from again.

“After hearing about the trouble in Gwangju in May of 1980, I would speak on the phone with Ok-hwan every day. On the evening of May 19, Ok-hwan said to me, ‘Mom, I’m fine — don’t worry about me.’ That was our last phone call,” she recalled.

No longer able to reach her son on the phone, Kim headed to Gwangju on May 22. The bus only took her as far as Hwasun County, meaning she had to walk the rest of the way.

When she reached the temple where Im had been staying, Kim was told her son had left on May 21, apparently headed home. Upon hearing that, Kim collapsed on the spot.

Kim roamed through the hill behind Chosun University, the direction her son would have been heading, but she couldn’t find any traces of him. She walked around Gwangju until her feet were blistered, stopping by Chonnam National University Hospital and Chosun University Hospital, but her son was nowhere to be seen.

Assuming that Im was dead, the family prepared burial garments for him and returned to Gwangju on June 2. Neighbors joined the family in searching for him. They visited the Sangmugwan army gymnasium near the old South Jeolla Provincial Office where the bodies of the dead had been stored, but by the time they arrived, the bodies had already been moved elsewhere.

Im Ok-hwan, who went missing during the Gwangju Uprising in May of 1980

(provided by the May 18th National Cemetery)

The family and friends returned to the slopes of the hill behind Chosun University. The troops enforcing martial law refused to give them permission to access the area, but the police let them in after learning the circumstances. They found items left behind by the troops — including soju bottles, bread wrappers, and truncheons — but nothing that could tell them what had become of Im. They tried digging with their bare hands, wondering if the teenager had been given a shallow burial, but failed to find anything.

Later, one of Im’s friends who had been staying at the temple told Kim that they’d been crossing the hill when they heard gunshots. The group had scattered at that point, and that was the last they saw of Im.

Im’s father, Im Jun-bae, became president of a group of family members of those who disappeared in the massacre in Gwangju, and Kim’s family members traveled to Gwangju, Seoul, and other areas along with bereaved families of massacre victims asking people to help find Kim’s son. But each time, a township official who was assigned to monitor Kim’s family stopped her from going. In Kim’s eyes, that official was just as bad as Chun Doo-hwan himself.

Researchers of the Gwangju Uprising think that Im’s disappearance may be linked to the 7th Airborne Brigade, which was deployed to Gwangju to suppress the uprising. When civic resistance stiffened after troops fired into a crowd of protesters in front of the old South Jeolla Provincial Office on May 21, 1980, government troops drew a cordon around the city to isolate it from the outside world.

The family and friends returned to the slopes of the hill behind Chosun University. The troops enforcing martial law refused to give them permission to access the area, but the police let them in after learning the circumstances. They found items left behind by the troops — including soju bottles, bread wrappers, and truncheons — but nothing that could tell them what had become of Im. They tried digging with their bare hands, wondering if the teenager had been given a shallow burial, but failed to find anything.

Later, one of Im’s friends who had been staying at the temple told Kim that they’d been crossing the hill when they heard gunshots. The group had scattered at that point, and that was the last they saw of Im.

Im’s father, Im Jun-bae, became president of a group of family members of those who disappeared in the massacre in Gwangju, and Kim’s family members traveled to Gwangju, Seoul, and other areas along with bereaved families of massacre victims asking people to help find Kim’s son. But each time, a township official who was assigned to monitor Kim’s family stopped her from going. In Kim’s eyes, that official was just as bad as Chun Doo-hwan himself.

Researchers of the Gwangju Uprising think that Im’s disappearance may be linked to the 7th Airborne Brigade, which was deployed to Gwangju to suppress the uprising. When civic resistance stiffened after troops fired into a crowd of protesters in front of the old South Jeolla Provincial Office on May 21, 1980, government troops drew a cordon around the city to isolate it from the outside world.

On the afternoon that Im went missing, the 872 enlisted soldiers and officers in the 7th Airborne Brigade, which had been stationed at Chosun University, moved across the hill behind the university to Neoritjae, a hill on the boundary between Gwangju and Hwasun. That overlapped with the route presumably taken by Im as he headed toward Hwasun on foot.

Kim says that all she wants is to find her son’s remains and bury them in a sunny spot. “My husband often laments that he probably won’t even find Ok-hwan’s bones before he dies. It makes me furious to think that powerless people like us are living with such pain while Chun Doo-hwan gets to die in comfort.”

The city of Gwangju recognized a total of 84 people as having disappeared during the Gwangju massacre. Six of them were identified when the bodies of victims were moved to a different cemetery in 2001, but the whereabouts of the other 78 remain unknown. For those who went missing without friends or family, hardly any information has yet to be ucovered.

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

No comments:

Post a Comment