Marcos Jr. continues to evade $353-million contempt judgment of US court

JAN 13, 2022 2:45 PM PHT

LIAN BUAN

Bongbong Marcos and mother Imelda settled with the Philippine government in 1992 and 1993, dividing their assets so they could be exonerated. But US courts maintain these violate a standing injunction.

MANILA, Philippines – Presidential aspirant Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. is yet to face a contempt judgment issued by a United States court in 1995 in connection with a human rights class suit against his late dictator-father, documents obtained by Rappler show. The amount involved for continuous contempt already reached $353 million in 2011.

Records from the United States District Court and Court of Appeals show that Marcos is being held in contempt for “contumacious conduct causing direct harm to [a class of human rights victims].” Based on the exchange rate on Thursday, January 13, the $353 million is already equivalent to about P18 billion.

The contempt judgment specifically names Bongbong and his mother Imelda as representative of the late dictator’s estate. The patriarch died in exile in Hawaii in 1989. His remains were brought home to Batac, Ilocos Norte, in September 1993. Despite protests, President Rodrigo Duterte granted him a hero’s burial in November 2016 – armed with a decision from the Supreme Court that favored the move.

“The judgment is entered personally against Imelda R. Marcos and Ferdinand R. Marcos. Since they served as executors of the Estate of Ferdinand E. Marcos, and their contemptuous acts were on behalf of the Estate, the Estate is in privity with them and subject to the judgment herein,” Judge Manuel Real of the District Court of Hawaii said in the judgment dated January 25, 2011.

This was affirmed by the US Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit in October 2012, that said “we hold that the $353,600,000 contempt judgment is properly enforceable by Hilao.” Hilao is Celsa Hilao, mother of student activist Liliosa Hilao, who was tortured and killed during Martial Law, and is the lead in the historic class suit against the late dictator.

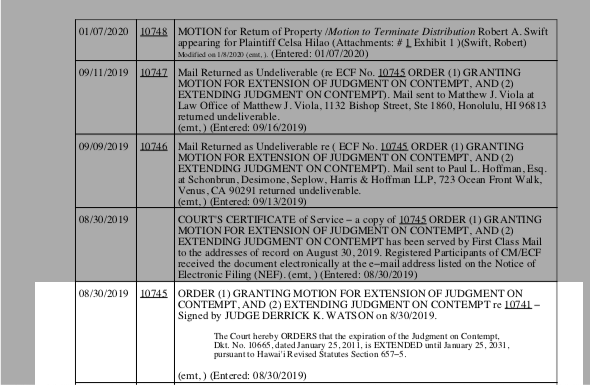

In August 2019, a new judge, Derrick Watson, extended the judgment on contempt to January 25, 2031, or nine years from now.

SOURCE. A page from the docket records of the US District Court of Hawaii for the case of Estate of Ferdinand E. Marcos Human Rights Litigation

Why does this matter?

Marcos Jr. is running for president in May 2022. At least P125 billion of his father’s estate is still under litigation as part of protracted efforts to recover the Marcoses’ ill-gotten funds and distribute them to Filipinos. The presidential aspirant continues to deny any wrongdoing by his father.

Even the tax of this estate is in dispute and cited by petitioners challenging Marcos’ candidacy before the Commission on Elections (Comelec). The petition of civic leaders, now up for resolution, says: “The failure of the Marcos family to pay the estate taxes is to the detriment of the Filipino people, as it represents once again a ‘Ferdinand Marcos,’ but this time his Junior, depriving the country and its people of money properly belonging to them.”

If Bongbong Marcos becomes president and goes to the US, it would trigger moves to enforce the judgment, even a request for a subpoena to face the court and explain, according to Robert Swift, the American lawyer working to recover assets to distribute to Martial Law victims. The same goes for Imelda.

If they still refuse to pay or snub a subpoena while in the US, “the US Court could hold them in criminal contempt and imprison them until they purge their contempt by answering questions about their assets,” Swift told Rappler in an email Thursday.

Bongbong settled with PH government, in contempt of US court

On November 20, 1991, the US District Court of Hawaii issued a preliminary injunction barring the family from touching their US assets. “The Court entered a permanent injunction on February 3, 1995, as part of the final judgment in the class action,” court records said.

Despite this, Imelda and Bongbong entered into two agreements with the Philippine government in June 1992 to “split and divide with the Republic all assets belonging to the Estate of Ferdinand E. Marcos.” Artworks in the United States were sold, and proceeds were divided between Imelda and the Philippine government.

Imelda and Bongbong entered into two additional agreements in December 1993, details of which were discovered by the American attorneys of the human rights victims only because they were disclosed in a Philippine court filing.

The 1993 agreements, the US court noted in its 1995 decision, “delineate with more specificity how the Estate’s assets are to be divided with the Republic of the Philippines and provide that the wife and children of Ferdinand E. Marcos are to receive 25% of the Estate’s assets tax free together with the dismissal of all criminal charges against them.”

“Two agreements were used instead of one in an apparent subterfuge to gain control over more than $365 million located in Switzerland,” said the court.

The agreements were held in violation of the US court’s injunction on the assets. Part of the 1995 judgment says Imelda and Bongbong must pay, renounce their settlements, deposit to the Court the proceeds from the artworks’ sale, and pay a fine of $100,000 per day to coerce them into complying.

The Marcoses appealed the decision to the US Court of Appeals, arguing that the sanctions were coercive and unenforceable.

Affirming the contempt judgment, the US Court of Appeals in 2012 said “even if Marcos is correct that the contempt sanction was coercive, it was also clearly compensatory.”

“Additionally, the district court explained that the $100,000 per day amount was necessary and appropriate because Marcos’s contumacious conduct was causing direct harm to Hilao, including $55,000 per day from lost interest and additional losses due to Marcos’s dilatory tactics,” said the US Court of Appeals when it ruled in 2012 that the contempt judgment was “properly enforceable.”

A Hawaii court had also awarded human rights victims $2 billion in damages, but the Philippine Court of Appeals in 2017 junked the enforcement petition based on lack of jurisdiction.

Rappler.com

No comments:

Post a Comment