"Moderate" Sens. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ). (TPM Illustration/Getty Images)

By Kate Riga

December 31, 2021

News outlets trot out the term every time Sens. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) make headlines: “moderates.”

Usually, these lawmakers are rating coverage and earning the moniker for bucking the party, or throwing some kind of obstacle in the path of their leaders’ agenda. Progressive politicians and Democratic constituents alike routinely bristle at the characterization of their party’s most obstinate members.

“Referring to the small handful of conservative Democrats working to block the president’s agenda as ‘moderates’ does grave harm to the English language and unfairly maligns my colleagues who are actually moderate yet by and large understand the stakes of this historic moment,” Rep. Mondaire Jones (D-NY) said recently.

But it’s not just Democrats. Yes, “moderate” Democrats are simply the Democrats who most annoy their party, regardless of their policy prescriptions. But those Republicans described as “moderate” are simply those who annoy former President Trump, regardless of their political ideology. “Moderate” voters don’t seem to share any common set of characteristics either.

It is a term freighted with connotation, and savvy politicians and voters have each long grasped that rhetorical work it does well enough to describe themselves with it. But in both cases, the word itself has become hopelessly squishy and largely devoid of any substantive meaning. In 2021, it says much more about how our politicians and voters want to be perceived than it does about what they actually believe.

As the two major parties have become increasingly homogenous in terms of their members’ policy positions, “moderate” has become more of a relational term than a policy descriptor.

“It’s used by members who need some distance from their national party,” Francis Lee, professor of politics and public affairs at Princeton University, told TPM.

For Manchin certainly, showing West Virginia voters that he’s not a rubber stamp for the Democratic agenda aligns with his political reality. The state voted for former President Donald Trump with a whopping 69 percent of the vote in 2020. Though it has a Democratic senator, it was second only to Wyoming in its near-complete loyalty to the Republican presidential candidate.

Unlike Manchin, Sinema lacks an obvious political rationale to routinely contradict her party. Hailing from a purple state that President Joe Biden won in 2020 — and contrasting sharply with a much more typical battleground state lawmaker in her fellow Arizona Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ) — Sinema has still, for some reason, staked her political wellbeing on tacking very publicly to the party’s right.

Where the two align is in messaging: They both want to signal to their home-state voters that they are not loyal Democratic foot soldiers. But a clue to the substantive emptiness of the “moderate” descriptor they share is how little they have in common otherwise.

Over the past few months, both have used the veto power every Democratic senator has in the evenly-split chamber ruthlessly, and often — but rarely over the same policy issue. Manchin took an axe to major climate change programs; Sinema supports them. Sinema blocked the party from collecting more taxes from the very wealthy; Manchin is all for upping taxes on the rich.

Further proof of the term’s divorce from any policy meaning comes from the Republican party, which has been jerked sharply to the right under the Trump presidency.

There, the crop of “moderates” usually includes lawmakers like Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) and Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY). They are people, in short, who are unfriendly to Trump, the leader of their party, and to much of the anti-democracy propaganda he peddles. But ideologically, they often hew closely to the basic beliefs that long comprised the Republican worldview.

“They are labeled as moderates even though a lot of them occupy a more conservative ideological space than Trump himself,” Alex Theodoridis, associate professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, told TPM. “Trump is all over the place ideologically; people like Liz Cheney or Ben Sasse or Mitt Romney are not.”

Part of the reason that the word has come to describe lawmakers’ willingness to buck their parties rather than their ideology or stance on policy is that there is no cohesive moderate voting bloc for these politicians to represent.

Voters who call themselves moderates have as little in common as the politicians that do the same. Often, they only look moderate because they hold a cornucopia of policy positions plucked from both parties. But these policy positions are often quite extreme.

“When we took a survey, the most popular position on immigration was to militarize the border, a very extreme conservative position, and the most popular position on marijuana was to completely legalize it at the national level — a relatively strong liberal position,” Doug Ahler, assistant professor of political science at Florida State University, told TPM.

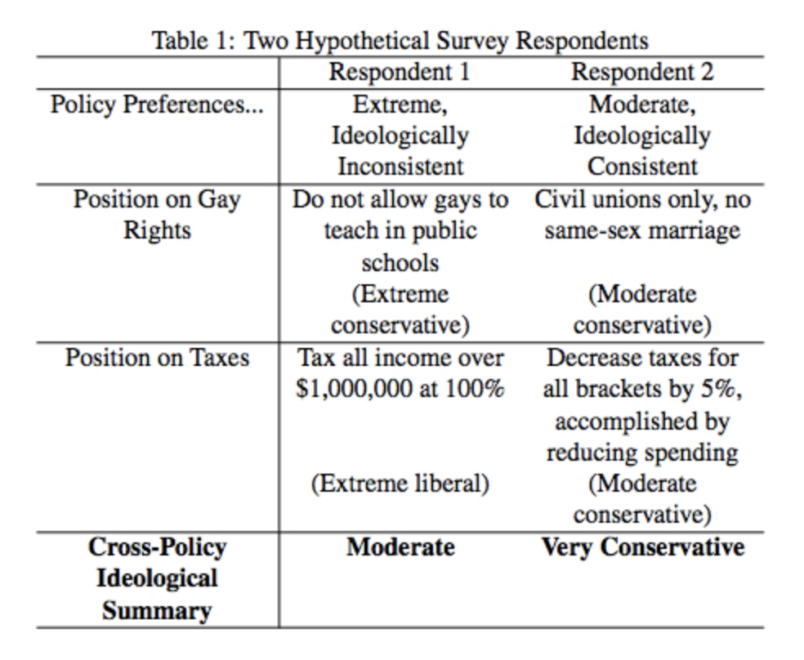

An example from Ahler’s coauthor David Broockman about how moderate labelling can be misleading. A person with one extreme conservative and extreme liberal view is a “moderate.” A person with two milder conservative views is “very conservative.”

Political science, Ahler said, hasn’t focused much on the extremity of each position voters hold in favor of capturing a comprehensive, and misleading picture. In his research, Ahler and coauthor David Broockman found that 71.3 percent of self-described moderates had at least one extreme policy position. Like moderate politicians, these voters don’t fit neatly into either party box. But that doesn’t mean they have much in common with each other, or a general coherent ideological philosophy a lawmaker could campaign to represent.

So the word “moderate” is not shorthand for policy positions or ideological beliefs or, really, anything at all. It’s simply a signal about how politicians and voters want to be perceived in relation to those around them. And for certain politicians, it does the extra work of painting them as independent from a party some of their base may distrust.

“It sounds kind of responsible,” Georgia State University political science professor Jennifer McCoy said. “If you’re moderate, you’re not extreme. It’s an attractive label that’s fairly meaningless in content.”

Kate Riga (@Kate_Riga24) is a D.C. reporter for TPM and a contributor to the Josh Marshall Podcast.

Political science, Ahler said, hasn’t focused much on the extremity of each position voters hold in favor of capturing a comprehensive, and misleading picture. In his research, Ahler and coauthor David Broockman found that 71.3 percent of self-described moderates had at least one extreme policy position. Like moderate politicians, these voters don’t fit neatly into either party box. But that doesn’t mean they have much in common with each other, or a general coherent ideological philosophy a lawmaker could campaign to represent.

So the word “moderate” is not shorthand for policy positions or ideological beliefs or, really, anything at all. It’s simply a signal about how politicians and voters want to be perceived in relation to those around them. And for certain politicians, it does the extra work of painting them as independent from a party some of their base may distrust.

“It sounds kind of responsible,” Georgia State University political science professor Jennifer McCoy said. “If you’re moderate, you’re not extreme. It’s an attractive label that’s fairly meaningless in content.”

Kate Riga (@Kate_Riga24) is a D.C. reporter for TPM and a contributor to the Josh Marshall Podcast.

No comments:

Post a Comment