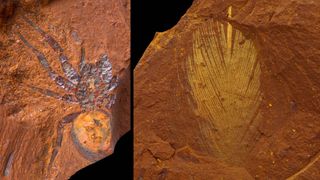

Scientists found thousands of preserved plants, spiders and insects dating to the Miocene Epoch.

Buried in Australia's so-called dead heart, a trove of exceptional fossils, including those of trapdoor spiders, giant cicadas, tiny fish and a feather from an ancient bird, reveal a unique snapshot of a time when rainforests carpeted the now mostly-arid continent.

Paleontologists discovered the fossil treasure-trove, known as a Lagerstätte ("storage site" in German) in New South Wales, in a region so arid that British geologist John Walter Gregory famously dubbed it the "dead heart of Australia" over 100 years ago. The Lagerstätte's location on private land was kept secret to protect it from illegal fossil collectors, while scientists excavated the remains of plants and animals that lived there sometime between 16 million and 11 million years ago.

The researchers unearthed remains that are unique in the Australian fossil record for the Miocene Epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), they reported in a new study. Most of the prior Miocene finds that other scientists have unearthed in Australia were bones and teeth from larger animals — which are commonly preserved in Australia's dry landscapes. However, the new cache held fossils of small and delicate creatures such as spiders and insects, as well as flora from the Miocene rainforest.

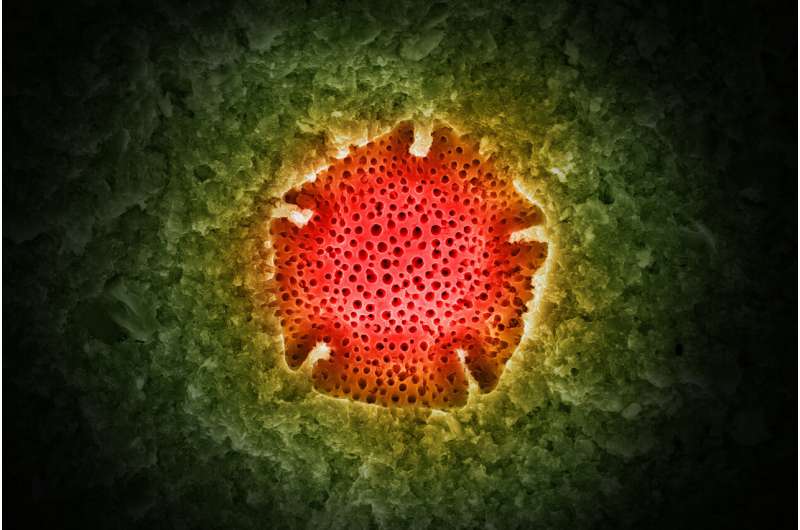

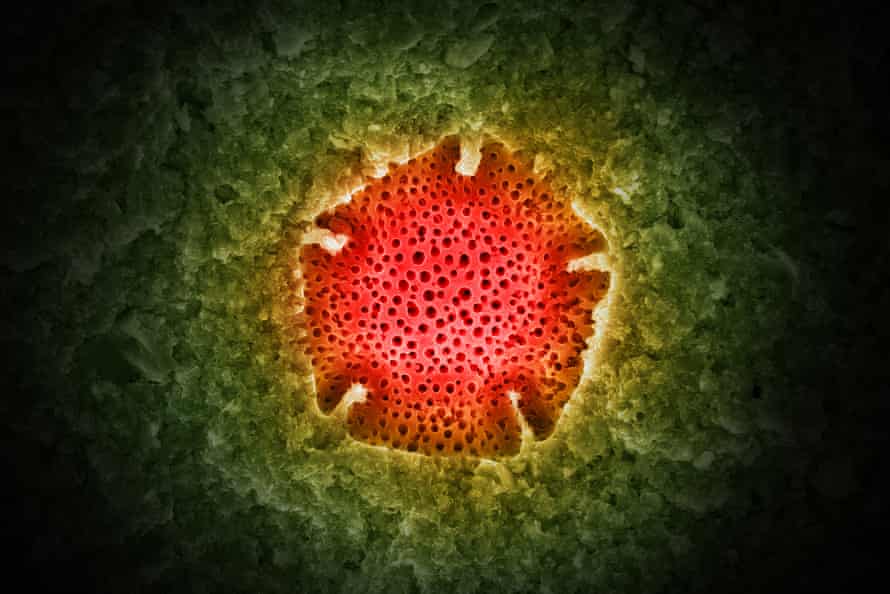

By examining the well-preserved fossils with scanning electron microscopes (SEM), the study authors were able to image details as fine as individual cells and subcellular structures. Some of the images even revealed animals' last meals, such as fish, larvae and a partially digested dragonfly wing preserved inside fishes' bellies. In other fossilized scenes, a freshwater mussel clung to a fish's fin, and pollen grains were stuck to insects' bodies.

"This site gives us unprecedented insight into what these ecosystems were like," lead study author Matthew McCurry, a curator of paleontology at the Australian Museum, told Live Science in an email. "We now know how diverse these ecosystems were, which species lived in them and how these species interacted."

Millions of years ago, this site was a lush rainforest ecosystem that was home to diverse plant and animal species. (Image credit: Alex Boermsa)

Paleontologists first visited the site — now named McGraths Flat — in 2017, after a farmer reported finding fossilized leaves in one of his fields. When the scientists investigated, "we were pleased to discover that the site yields a much wider range of fossils, including the remains of insects, spiders and fishes," McCurry said.

The fossil-bearing rock layer measures between 11,000 and 22,000 square feet (1,000 and 2,000 square meters), and paleontologists have thus far excavated just over 500 square feet (50 square m), according to McCurry. A matrix of iron-rich rock called goethite surrounded the fossils on top of a layer of sandstone. Plants and animal remains in a stagnant pool were likely encased in iron and other minerals after runoff from nearby basalt cliffs drained into the pool, known in Australia as a billabong, which preserved them in exquisite detail.

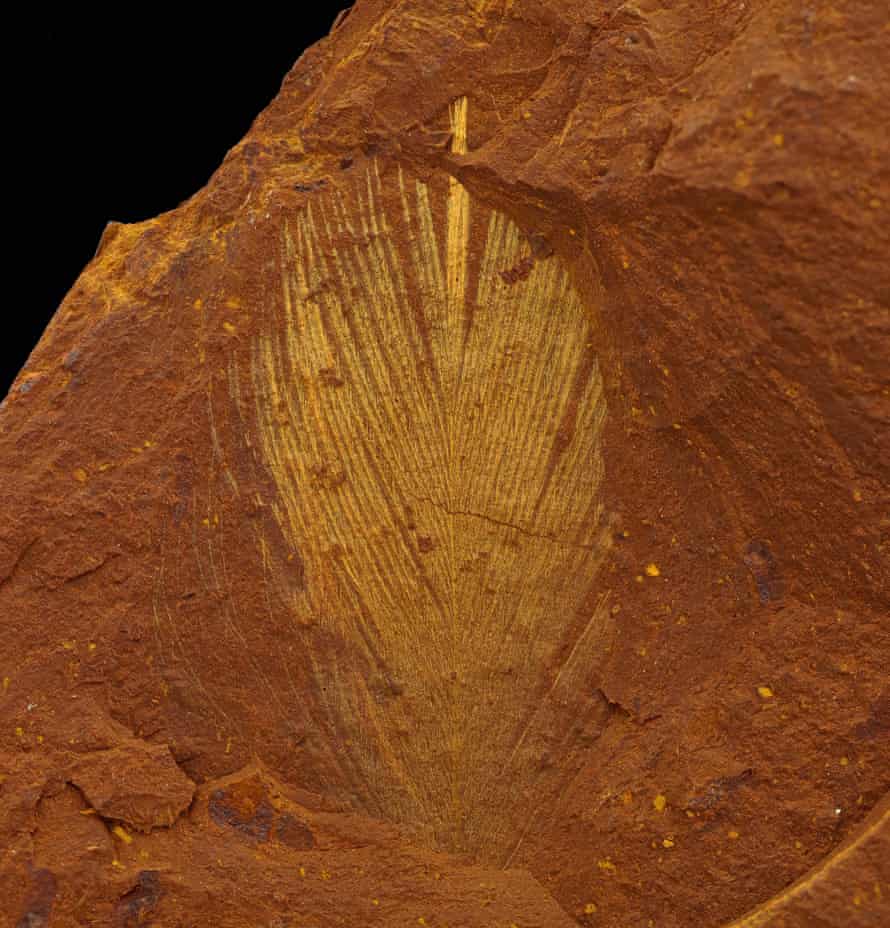

Now, millions of years later, researchers have begun piecing together the fossils to build a portrait of an extinct Australian rainforest. They found leaves from flowering plants, pollen, fungal spores, more than a dozen specimens of fish, "a wide diversity of fossilized insects and arachnids," and a feather from a bird that was about the size of a modern sparrow, the study authors reported. Analysis of the preserved leaves suggests that the average temperature at the time was about 63 degrees Fahrenheit (17 degrees Celsius).

Cingulasporites ornatus spores were among the traces of ancient life preserved at McGraths Flat.

"I find the spider fossils the most fascinating," McCurry told Live Science. Until now, only four fossil spiders were known from Australia, and researchers have so far found 13 spider fossils at McGrath Flats, McCurry said.

Preserved soft tissues in the feather and in the fishes' eyes and skin held another exciting detail: pigment-storing cell structures called melanosomes. Though the color itself isn't preserved, scientists can compare the shape, size and stacking patterns in the fossil melanosomes to those in modern animals. In doing so, paleontologists can often reconstruct the colors and patterns in extinct species, study co-author Michael Frese, an associate professor of science at the University of Canberra in Australia, said in a statement.

While much has been discovered at McGraths Flat, "this is really only the beginning of the work on the fossil site," McCurry said. "We now know the age of the deposit and how well-preserved the fossils are, but we have years of work ahead of us to describe and name all of the species we are finding. I think that McGraths Flat will become extremely important in building a more accurate picture about how Australia has changed over time."

The findings were published Friday (Jan. 7) in the journal Science Advances.

Originally published on Live Science.

Life in the 'dead' heart of Australia

A team of Australian and international scientists led by Australian Museum (AM) and University of New South Wales (UNSW) paleontologist Dr. Matthew McCurry and Dr. Michael Frese of the University of Canberra has discovered and investigated an important new fossil site in New South Wales, Australia, containing superb examples of fossilized animals and plants from the Miocene epoch. The team's findings were published today in Science Advances.

The new fossil site (named McGraths Flat), located in the Central Tablelands, NSW near the town of Gulgong, represents one of only a handful of fossil sites in Australia that can be classified as a 'Lagerstätte'– a site that contains fossils of exceptional quality.

Over the last three years a team of researchers has been secretly excavating the site, discovering thousands of specimens including rainforest plants, insects, spiders, fish and a bird feather.

Dr. McCurry said the fossils formed between 11 and 16 million years ago and are important for understanding the history of the Australian continent.

"The fossils we have found prove that the area was once a temperate, mesic rainforest and that life was rich and abundant here in the Central Tablelands, NSW," McCurry said.

"Many of the fossils that we are finding are new to science and include trapdoor spiders, giant cicadas, wasps and a variety of fish,' McCurry said.

"Until now it has been difficult to tell what these ancient ecosystems were like, but the level of preservation at this new fossil site means that even small fragile organisms like insects turned into well-preserved fossils," McCurry said.

Associate Professor Michael Frese, who imaged the fossils using stacking microphotography and a scanning electron microscope (SEM), said that the fossils from McGraths Flat show an incredibly detailed preservation.

"Using electron microscopy, I can image individual cells of plants and animals and sometimes even very small subcellular structures," Frese said.

"The fossils also preserve evidence of interactions between species. For instance, we have fish stomach contents preserved in the fish, meaning that we can figure out what they were eating. We have also found examples of pollen preserved on the bodies of insects so we can tell which species were pollinating which plants," Frese added.

"The discovery of melanosomes (subcellular organelles that store the melanin pigment) allows us to reconstruct the color pattern of birds and fishes that once lived at McGraths Flat. Interestingly, the color itself is not preserved, but by comparing the size, shape and stacking pattern of the melanosomes in our fossils with melanosomes in extant specimens, we can often reconstruct color and/or color patterns," Frese explained.

The fossils were found within an iron-rich rock called 'goethite'—not usually thought of as a source of exceptional fossils." We think that the process that turned these organisms into fossils is key to why they are so well preserved. Our analyses suggest that the fossils formed when iron-rich groundwaters drained into a billabong, and that a precipitation of iron minerals encased organisms that were living in or fell into the water," McCurry added.

Dr. McCurry said that the fossilized plants and animals are similar to those found in rainforests of northern Australia, but that there were signs that the ecosystem at McGraths Flat was beginning to dry.

"The pollen we found in the sediment suggests that there might have been drier habitats surrounding the wetter rainforest, indicating a change to drier conditions," McCurry said.

Executive Director, Science, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, Professor David Cantrill, said that the variety of fossils preserved, together with an extraordinary fidelity of preservation, allows for unprecedented insights into an important time in Australia's past, a time when mesic ecosystems still dominated the continent.

"The McGraths Flat plant fossils give us a window into the vegetation and ecosystems of a warmer world, one that we are likely to experience in the future. The preservation of the plant fossils is unique and provides important insights into a time period for which the fossil record in Australia is rather poor," Cantrill said.

Australian Museum Chief Scientist and director of the AM's Research Institute, Professor Kristofer Helgen said that the fossil site brings to life a picture of outback Australia that we can now barely believe existed.

"Australia is the most unique continent biologically, and this site is extremely valuable in what it tells us about the evolutionary history of this part of the world. It provides further evidence of changing climates and helps fill the gaps in our knowledge of that time and region," Helgen said.

"The AM has a rich history of expeditions and scientific research, and we love that the public is always fascinated by these fundamental human endeavors of exploration and discovery," Helgen added.

Field work at McGraths Flat was funded through the generous donation from a descendant of Robert Etheridge, an English paleontologist who came to Australia in 1866. Etheridge joined the Australian Museum in 1887 as Assistant Paleontologist and in 1895 was made Curator of the Museum.

Australian Museum director and CEO, Kim McKay AO, said that under Etheridge the AM's collections were greatly enhanced and that he also launched a program of expeditions—the first being to Lord Howe Island—which continues to this day.

"There has been a long tradition at the AM of significant, scientific discovery. It is great to see that this continues with Dr. McCurry's work, which is directly linked to our earlier paleontologist, curator and director, Robert Etheridge," McKay said.

McGraths Flat

First found in 2017, McGraths Flat is named after Nigel McGrath who discovered the first fossils from the site. The site is located near Gulgong in central NSW (Gulgong is a Wiradjuri word that means "deep waterhole").

The Miocene Epoch (~23–5 million years ago) was a time of immense change in Australia. The Australian continent had separated from Antarctica and South America and was drifting northwards. When the Miocene began there was enormous richness and variety of plant and animal life in Australia. But at around 14 million years ago an abrupt change in climate known as the "Middle Miocene Disruption" caused widespread extinctions. Throughout the latter half of the Miocene, Australia gradually became more and more arid, and rainforests turned into the dry shrublands and deserts that now characterize the landscape. The newly discovered fossil site, McGraths Flat, provides an unprecedented look into what Australian ecosystems were like prior to this aridification.Rare pig-nosed turtles once called Melbourne home

More information: M. R. McCurry et al, A Lagerstätte from Australia provides insight into the nature of Miocene mesic ecosystems, Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm1406. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm1406

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by Australian Museum

Likely to contain dozens of undiscovered species, the site is so well-preserved that the contents of fish stomachs and breathing apparatus of spiders can be seen

‘A magical window into a diverse ecosystem’: Dr Matthew McCurry removes rock containing fossils from the pit at McGraths Flat in NSW.

by Graham Readfearn

Fri 7 Jan 2022

The Australian paleontologist Matthew McCurry was digging for Jurassic fossils when a farmer dropped by with news of something he’d seen in his paddock – a fossilised leaf in a piece of hard brown rock.

Fossil leaves are not usually anything to write home about, but the spot was close, so McCurry and his colleague Michael Frese went to take a look.

What they found in that dusty paddock near the New South Wales town of Gulgong five years ago has had paleontologists – at least those few who have known the secret – in awe.

Encased in the rocks are the inhabitants of a rainforest that existed in that now dry and arid spot about 15m years ago.

“There’s a whole ecosystem preserved,” says McCurry, curator of paleontology at the Australian Museum and a lecturer at the University of New South Wales.

As their hammers split the iron-rich rocks, thousands of fossils have been revealed – from flowering plants to fruits and seeds, insects, spiders, pollen and fish. There will be scores of new species.

McCurry and his colleagues revealed the site, and their initial findings, in the journal Science Advances on Saturday Australian time.

“Paleontologists around the world will drool when they see this paper,” said Prof John Long, a famed fossil hunter from Flinders University who got a sneak peek at some of the fossils a year ago.

Such an array of specimens in one spot has allowed the Australian scientists to build an incredibly detailed picture of a little-known ecosystem from a period known as the mid-Miocene – a time just before the continent dried out to be what it is today.

As well as the huge number of different specimens at the site – known as McGraths Flat – it is the fossils’ immaculate preservation that is delivering an unprecedented depth of information.

Under a microscope, there is detail down to below a micron in width (a spider’s thread is about three microns).

The breathing apparatus of spiders and the contents of fish stomachs are visible. The cells that can reveal the original colour of a feather have been preserved. A sawfly was frozen in time with dozens of pollen grains attached to its head.

Since that first visit, McCurry and his colleagues have unearthed a treasure trove of fossils. When the rocks are broken apart, they tend to split the fossilised remains in half like an instant autopsy, revealing internal organs and tissues.

Fish stomachs are so well preserved McCurry says they can see what that fish ate – about 15m years ago – in the moments before its demise.

“We can see the food in the stomach, like a dragonfly wing. But commonly, it’s insect larvae,” he says.

Long saw some of the fossils last year when he visited McCurry at the Australian Museum.

“Fossils are often preserved as bits and pieces or fragments. Occasionally you might get a whole organism. But this is truly exceptional preservation,” he says.

“You have complete organisms ... soft tissue ... cellular preservation. There’s a spider with its breathing system beautifully preserved. It’s a Xanadu.

“There’s all the diversity with a great range of organisms from fungi to plants and fish, and also you have their interaction. There’s evidence of behaviour. It has all the attributes of a world-class fossil deposit, of which we have very, very few in Australia.”

“It’s a bit of a Rosetta Stone of the full ecology of this middle Miocene environment. We have no other window into that period that tells us what that part of Australia was like.”

Fortunate fossils

New fossil sites are rare finds, and this one was almost missed. McCurry admits he drove past it at least once, oblivious to what was there.

On his first visit with Frese they found rocks rich in iron, unusually hard to split, and of a type not known for preserving fossils.

But immediately, the pair found what they thought were aquatic insects. Using a microscope Frese had in his car, they could see tiny midges preserved. “That’s when we realised how special the fossils were,” McCurry says.

Advertisement

Finding fossilised pollen allowed the scientists to accurately date the site.

Little is known about the ecosystems of the mid-Miocene period.

McCurry says there are likely to be “dozens, if not hundreds” of species new to science that have already been collected. The researchers have found probable new species preserved in the rock deposit between 50cm and 80cm thick at a rate of more than one a day. There have been eight field excavations so far.

Even though only two square metres are excavated each time, about 2,000 specimens have been collected. Now follows the painstaking process of checking each one against known records of flora and fauna.

Using analysis of the huge array of plant leaves at the site, the team have even been able to estimate the climate of the area. Warm months were about 26C and cool months as low as 7C.

Almost a metre of rain would have fallen in a month in the wet season – the region’s modern climate is hotter but much drier, with the wettest month averaging just 70mm.

Feather fossil

While much of the team go through the vast array of flora and fauna, Dr Jacqueline Nguyen, an expert in the evolution of birds at the Australian Museum, has been mostly fixated on the only evidence found so far of the birds that were in the rainforest. That is, one single fossilised feather about the size of a fingerprint.

“Fossilised feathers are incredibly rare,” she says. “Most are from the Cretaceous, but from the Miocene we only have this one. I’m super excited.”

The fossil feather is so detailed that Nguyen and her colleagues have been able to see the parts of the cells that give the feather its colour. This feather – probably from the bird’s body rather than wing – was likely dark or iridescent.

“Even though it’s just one feather, it’s a tantalising hint at what’s to come. Maybe we’ll find a bird skeleton.”

Frese, who is a virologist by training, has been examining the fossils under microscopes for several years.

“I was blown away by the detail,” he says. “I love the way the fossils present themselves. Usually you just see the surface, but here it always splits in half and you see the inside of a spider leg or the inside of pollen.”

The secret to the fossils’ preservation is up for debate, but McCurry thinks it would have happened over hundreds of years rather than in a sudden event.

Iron-rich water, maybe from nearby outcrops, could have flowed into a shallow billabong, periodically deoxygenating the water, killing the organisms or encasing flora and fauna in sediment that turns into the rocks found in the field.

McCurry admits he’s relieved to be able to tell the world about the discovery.

“This has been a marathon,” he says. “It’s a really important find and it’s going to keep us going for a long time.”

No comments:

Post a Comment