The Propaganda Engulfing Jamal Khashoggi

January 5, 2022

As’ad AbuKhalil writes this “friend” of Western journalists was close to the ruthless regime, even to the commander of his own eventual assassination squad. He will always be remembered as the obedient servant of various Saudi princes and as an early champion of bin Laden.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

With great fanfare and laudatory reviews in mainstream media, Showtime released the documentary Kingdom of Silence last year about the life and death of Jamal Khashoggi. A cult has been constructed around the person of Khashoggi throughout Western media (but not in Arab media) and the documentary distorts not only the history of the man but even his resonance in the Arab world.

The documentary does not measure up to the standards of a journalistic film, and it does not adhere to fairness and diversity of opinions. It is hagiography through and through. Not one critic of Khashoggi was interviewed, and a retired U.S. diplomat managed to represent the Saudi regime’s point of view. The voiceless Saudi opposition (which had no links to Khashoggi) remained so.

Lawrence Wright plays a major role in the film, commenting not only about Khashoggi but also about Arab politics (Wright has no knowledge of Arabic and no training in Middle East studies although he writes on “terrorism” for The New Yorker and wrote a script for the movie, the Siege, which upset the bulk of the Arab-American community).

Wright, like almost all Western journalists, refers to Khashoggi as a “friend”—as do most people who appear in the film (am I the only one left who does not call Khashoggi a friend?). This raises a question: here was a man who dedicated his life to the service of various Saudi princes and was as a “friend” of members of the DC media establishment. Would any of those journalists dare refer to a journalist working for Syrian or Iranian propaganda outlets as “a friend?”

Their closeness to Khashoggi over the years implicates them in the way they subject pro-U.S. despotic regimes to less scrutiny than to regimes opposed to the U.S.. This type of journalist holds particular scorn for despotic regimes that aren’t part of the American order in the Middle East.

Was Khashoggi really a friend to all those people mentioned in the documentary? How many friends can one accumulate in a lifetime? This is ironic because the real friends of Khashoggi in Arab (mostly Saudi) media denounced him or distanced themselves from him after his death, while Western journalists strived to claim the closest friendship.

Supported Saudi Crackdown

Kingdom of Silence doesn’t even promise to tell the story fairly or honestly. An actual close friend of Khashoggi’, Maggie Mitchell Salem, managed to describe his polygamous deception as “romantic.”

What you don’t hear in this documentary is about the decades Khashoggi devoted to the service of Saudi propaganda while men and women were beheaded for holding the wrong views. There is just one scene in the film in which you see Khashoggi on U.S. television defending a crackdown by the Saudi government. He defended shooting protesters because they weren’t killed.

This “friend” of Western journalists was close to the ruthless regime, even to the commander of his own eventual assassination squad. They got to know each other when the commander served as an intelligence man at the Saudi embassy in London where Khashoggi was chief of propaganda operations after Sep. 11.

[Ed.: Kingdom of Silence is by Alex Gibney, who made a thoroughly misleading documentary about Julian Assange in 2013, that among things portrayed Assange as paranoid about being extradited to the United States.]

No Professional Standards Allowed

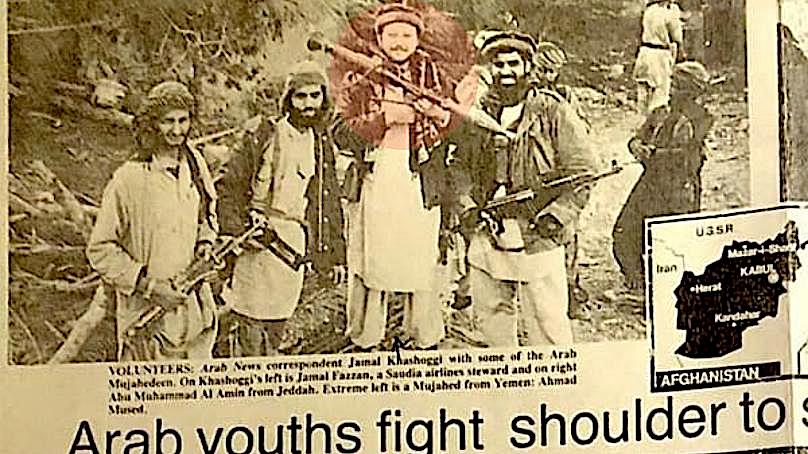

Newspaper clip showing Khashoggi (center) as Arab News correspondent in Afghanistan, 1980s.

Kingdom of Silence manages to discuss how much Khashoggi cared about the journalistic profession and its standards when he worked for decades as a journalist in Saudi Arabia—of all places. But there are no professional standards allowed in Saudi regime media, and all newspapers serve as mere mouthpieces for various princes.

Khashoggi knew how the media game is played and always attached himself to a prince at certain moments. He worked first for Prince Khalid Al-Faysal, before serving his brother, Turki Al-Faysal. He knew the latter when he was chief of Saudi intelligence and Khashoggi was a “correspondent” “covering” Osama bin Laden and his “struggle” against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. (There is a picture of Khashoggi from that era holding an AK-47, and he may have fought alongside bin Laden and his band of religious fanatics).

The lines between Saudi journalism and intelligence were very thin; an editor of two Saudi newspapers, Jihad Khazen, admitted that he used to receive “reports” from the Saudi intelligence chief and that he would publish them as articles in Al-Hayat (a defunct mouthpiece of Prince Khalid bin Sultan). Toward the end of his career, Khashoggi attached himself to Prince Al-Walid bin Talal, who quickly fell out of favor when Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman took over. That was the true story of Khashoggi’s “dissent” or defection. His mentor-prince was no longer favored.

Dangerously Close to the Brotherhood

There is a missing element in the documentary, which applies to all discussions about Khashoggi in the Western press. Khashoggi was no advocate of democracy as he posed in his last year, conveniently for his stint at The Washington Post. He was at odds with Riyadh by being very close to the Muslim Brotherhood and to Qatar. His name is being circulated and honored (through various institutes and academies that bear his name) by the Qatari regime.

Kingdom of Silence claims that Khashoggi was a supporter of the “Arab Spring.” That was not true at all. His stance on the Arab uprising was a an exact replica of the stance by Qatar: the regime supported uprisings only in countries where the Muslim Brotherhood had a good chance of seizing power, and it opposed democratization where the Brotherhood had none.

For that, the Qatari regime and Khashoggi personally supported the brutal Saudi-Bahraini crushing of the rebellion in Bahrain in 2011. There is an unspoken agreement in the Western press to never mention that Khashoggi (the early fan and advocate of bin Laden) was politically close to the Muslim Brotherhood and to Qatar. In fact, several of the people who spoke in the documentary about Khashoggi were people who are also close to either Qatar or the Muslim Brotherhood (or to both, as in the case of Tawakkul Karman).

Glamorizing the Man

Jamal Khashoggi in still from Kingdom of Silence. (Showtime)

The film is part of an effort underway to glamorize and embellish the life of Khashoggi. Many members of the Western establishment in Washington are excessively trying to honor his memory. Perhaps some—as Maggie Mitchell Salem admitted in the documentary—feel guilty because they wanted him to be a “native” voice who could frustrate Donald Trump’s policies toward the Kingdom. Of course, Joe Biden has continued the same pro-Saudi policies as his predecessor but with little opposition or consternation from the mainstream media.

Western media wants to turn Khashoggi into an Arab hero. Some may owe him a debt because he facilitated the work of Western correspondents inside the Kingdom. But the notion that he was some pan-Arab symbol of political courage is laughable. Khashoggi is remembered—and will always be remembered—as the obedient servant of various Saudi princes and as an early champion of bin Laden.

Wright maintains that Khashoggi was the only Saudi dissident when there are thousands of courageous men and women who languish in Saudi prisons; their names unknown to the likes of Wright and other Washington hacks.

One can’t dismiss the decades Khashoggi’s service to the crown simply because in the last year of his life he wrote vapid, unoriginal articles about the virtues of democracy (in general terms and without holding the U.S. and Western powers accountable for their complicity in the lack of democracy in the Arab world).

There is another Khashoggi documentary in the making and Qatar and Western media will continue to keep his name afloat. Championing Khashoggi is safe because he never took positions that were offensive to the U.S. government.

Kingdom of Silence reminds us that he supported the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and took overtly sectarian stances when it was in the interest of the U.S.-Israeli alliance. Khashoggi wasn’t consistent in his messaging in Arabic and English and those who watch the documentary will get yet another confirmation that Khashoggi’s articles in The Washington Post were not really authored by him.

The documentary spoke little about the dissent in Saudi Arabia that has existed long before the ascension of King Salman to the throne. Contrary to claims by Khashoggi and by this documentary, repression in the Kingdom did not start with Muhammad bin Salman.

What is different is that bin Salman killed a journalist who was close to Western media. That is crossing a red line, not beheading of scores of people in public squares in Riyadh. Western media may champion Khashoggi all they want but they can’t turn a decades-long propagandist for the Saudi regime into a hero.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002) and The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

No comments:

Post a Comment