New book claims intercepted cables sent in second world war by Allen Dulles, later head of CIA, enabled disinformation campaign

The myth of Nazis barricading themselves on snowy mountaintops later became a staple of such films as Where Eagles Dare, starring Clint Eastwood and Richard Burton. Photograph: MGM/Allstar

Philip Oltermann in Berlin

@philipoltermann

Mon 3 Jan 2022

A US spymaster inadvertently helped the Nazis develop one of the most effective disinformation campaigns of the second world war by spreading rumours about Hitler’s plans for a Where Eagles Dare-style Alpine redoubt, a historian with access to classified US military records has found.

The myth that the Nazis were amassing weapons and crack units of 100,000 fanatical soldiers in the spring of 1945 for a last stand in the Austro-Bavarian Alps was without any basis in fact but had a powerful hold on the imagination of American and British military leaders, who feared it could prolong the war for years.

Thomas Boghardt, a German historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington DC, argues in a new book that the myth of an Alpine Nazi fortress was not a crucial factor behind American forces abandoning the race to Berlin in favour of a southward push but was one that US spycraft had a hand in making.

The Nazi leadership first got wind of allied fears of a mountaintop last stand in 1944, after the SS’s intelligence service intercepted a cable sent from the US embassy in Berne, Switzerland. As Boghardt shows in Covert Legions: US Army Intelligence in Germany 1944-1949, the message had most likely been sent by Allen Dulles, later the head of the CIA during the Bay of Pigs invasion fiasco but at the time the Berne station chief for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

As Covert Legions shows, allied forces were extremely susceptible to disinformation campaigns in the final stages of the war, with Field Marshal Montgomery arrested at one point as an impostor by American guards following a rumour that the Germans were planning to impersonate the British commander.

After the end of the war, Nazis barricading themselves on snowy mountaintops became a staple of swashbuckling war movies, such as 1968’s Where Eagles Dare, starring Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood.

However, while some allied intelligence reports explicitly cited the Alpine redoubt theory as an argument for an allied push into southern Germany in 1945, Boghardt rejects the idea that it played a crucial part in shaping the second world war endgame and setting the ground for cold war tensions with the Soviet Union, as Winston Churchill later claimed.

The US decision not to back a British plan for a “pencil-like thrust” to Berlin likely owed more to the fact that the Red Army was already within 20 miles of the German capital while Anglo-American forces were still 300 miles away, he said, and a deal to divide up the city had already been agreed.

“My impression is that the US command ultimately didn’t really believe in the Alpine redoubt myth, but may have kept it alive to persuade the British of their overriding strategy.”

Philip Oltermann in Berlin

@philipoltermann

Mon 3 Jan 2022

A US spymaster inadvertently helped the Nazis develop one of the most effective disinformation campaigns of the second world war by spreading rumours about Hitler’s plans for a Where Eagles Dare-style Alpine redoubt, a historian with access to classified US military records has found.

The myth that the Nazis were amassing weapons and crack units of 100,000 fanatical soldiers in the spring of 1945 for a last stand in the Austro-Bavarian Alps was without any basis in fact but had a powerful hold on the imagination of American and British military leaders, who feared it could prolong the war for years.

Thomas Boghardt, a German historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington DC, argues in a new book that the myth of an Alpine Nazi fortress was not a crucial factor behind American forces abandoning the race to Berlin in favour of a southward push but was one that US spycraft had a hand in making.

The Nazi leadership first got wind of allied fears of a mountaintop last stand in 1944, after the SS’s intelligence service intercepted a cable sent from the US embassy in Berne, Switzerland. As Boghardt shows in Covert Legions: US Army Intelligence in Germany 1944-1949, the message had most likely been sent by Allen Dulles, later the head of the CIA during the Bay of Pigs invasion fiasco but at the time the Berne station chief for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

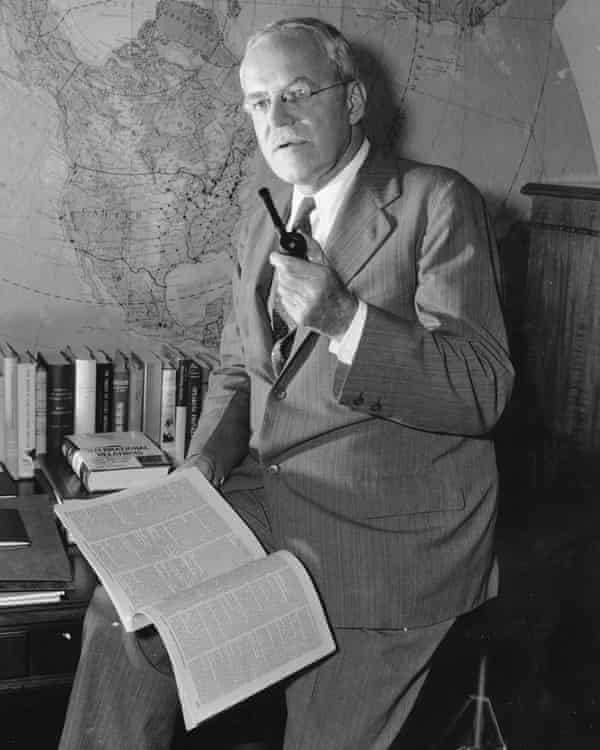

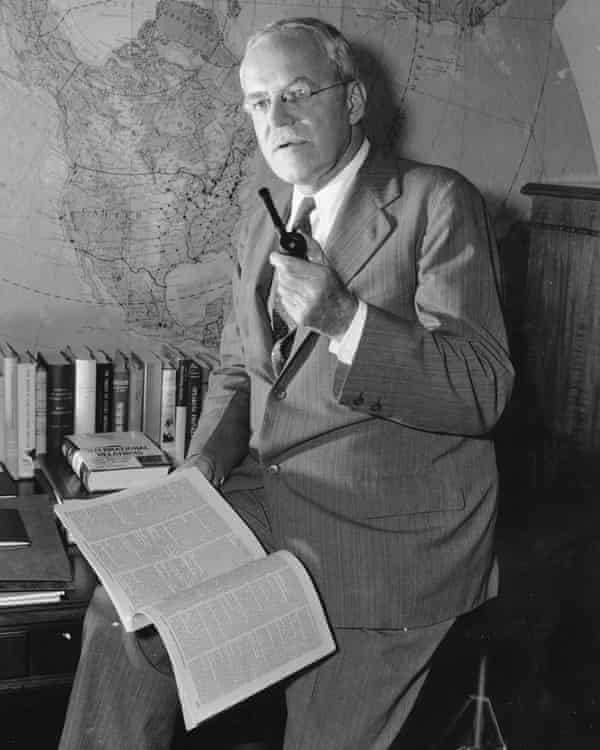

Allen Dulles, pictured in 1954, when he was the director of the CIA.

Photograph: Associated Press

British intelligence had discovered that the special cipher used to secure Dulles’s communications had been compromised, but the American spymaster continued to ignore their warnings, driving one irate British agent to despair.

“[C]ould you report to the fool [Dulles] who knows his code was compromised if he has used that code to report meetings with anyone, Germans probably identified persons concerned and use them for stuffing [disinformation]”, the agent vented to his station chief. “He swallows easily.”

As the British had feared, Goebbels’s propaganda ministry would spend the following months building up the myth of a German defence effort in Austria and Bavaria via disinformation and media reports, hoping a sidetracked US military leadership could be drawn into separate peace talks or even an alliance against the Soviets.

“Dulles was a very capable case officer who excelled at working with human sources, but when it came to signals intelligence he was indeed highly negligent,” Boghardt told the Guardian.

British intelligence had discovered that the special cipher used to secure Dulles’s communications had been compromised, but the American spymaster continued to ignore their warnings, driving one irate British agent to despair.

“[C]ould you report to the fool [Dulles] who knows his code was compromised if he has used that code to report meetings with anyone, Germans probably identified persons concerned and use them for stuffing [disinformation]”, the agent vented to his station chief. “He swallows easily.”

As the British had feared, Goebbels’s propaganda ministry would spend the following months building up the myth of a German defence effort in Austria and Bavaria via disinformation and media reports, hoping a sidetracked US military leadership could be drawn into separate peace talks or even an alliance against the Soviets.

“Dulles was a very capable case officer who excelled at working with human sources, but when it came to signals intelligence he was indeed highly negligent,” Boghardt told the Guardian.

As Covert Legions shows, allied forces were extremely susceptible to disinformation campaigns in the final stages of the war, with Field Marshal Montgomery arrested at one point as an impostor by American guards following a rumour that the Germans were planning to impersonate the British commander.

After the end of the war, Nazis barricading themselves on snowy mountaintops became a staple of swashbuckling war movies, such as 1968’s Where Eagles Dare, starring Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood.

However, while some allied intelligence reports explicitly cited the Alpine redoubt theory as an argument for an allied push into southern Germany in 1945, Boghardt rejects the idea that it played a crucial part in shaping the second world war endgame and setting the ground for cold war tensions with the Soviet Union, as Winston Churchill later claimed.

The US decision not to back a British plan for a “pencil-like thrust” to Berlin likely owed more to the fact that the Red Army was already within 20 miles of the German capital while Anglo-American forces were still 300 miles away, he said, and a deal to divide up the city had already been agreed.

“My impression is that the US command ultimately didn’t really believe in the Alpine redoubt myth, but may have kept it alive to persuade the British of their overriding strategy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment