Now is an apt moment to read up on a US marine named Smedley Butler.

Crawford Kilian 22 Feb 2022TheTyee.ca

Crawford Kilian is a contributing editor of The Tyee.

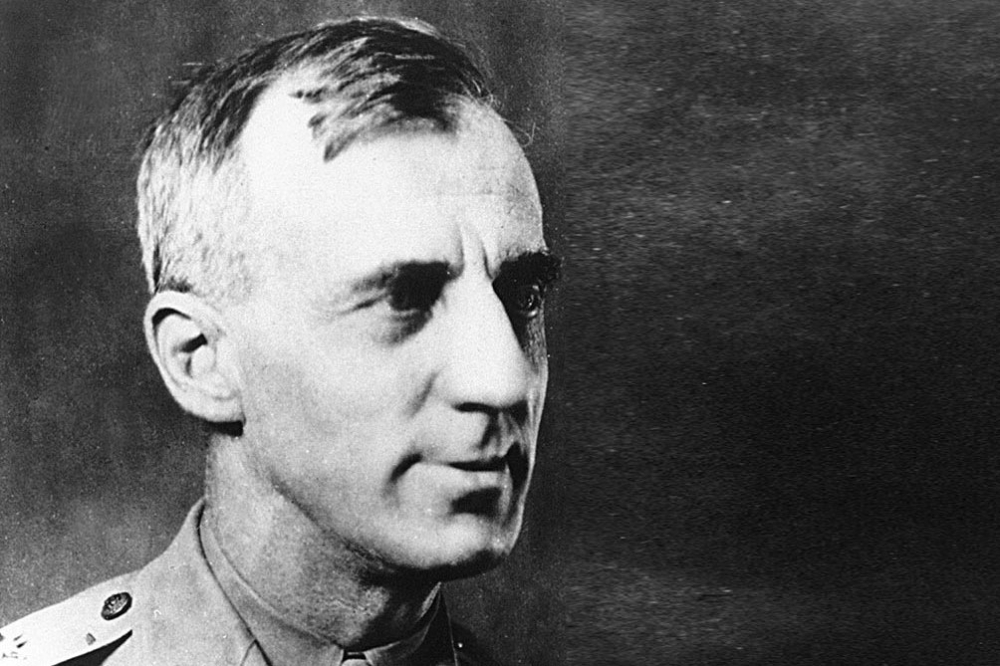

Smedley Butler died on the eve of the Second World War:

‘An idealistic boy grown into a monster, he served his country by ruining other countries beyond repair.’

Photo via Wikimedia.

Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire

By Jonathan Katz

St. Martin’s Press (2022)

The life and confessions of Smedley Butler make interesting reading as schemers subvert the electoral process in the U.S., and as Canadians behold the assault on their own government by capital occupiers backed by mysterious money and tactical assistance.

Who is Smedley Butler? Once upon a time, he was America’s archetypal warrior, a U.S. Marine general who became the model for soldiers in Hollywood movies. He was literally present at the creation of the American empire, from Latin America to the Philippines — a professional toppler and installer of regimes who shaped over a century of imperial policy and administration.

Butler was even approached to lead a coup against his old friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt. For the masters of high finance who tried to recruit him for that job, democracy had become an inconvenience to be tossed away.

Today Butler is almost forgotten, an embarrassment even to the marine corps. That’s because he described his 30-year career by calling himself a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. He gave anti-war speeches on college campuses and died of cancer in 1940, the day before Hitler invaded Russia.

Jonathan Katz has resurrected Butler from 80 years of obscurity in this surprising and very well-written book. He has also explored a part of American history that Americans prefer to forget, and examined the 21st-century consequences of 19th-century presidents’ imperial ambitions.

Smedley Butler was a lucky man, born into a prosperous Philadelphia Quaker family; his father was a congressman. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Butler was only 16. Despite his age and his family’s Quaker pacifism, he was eager to help liberate Cuba from the Spanish empire. He managed to get himself into the U.S. Marines and (after very little training) shipped to Cuba as a second lieutenant. Of all places, he came ashore at Guantánamo, where he took part in some combat.

Enforcer for the banks

Then he was caught up in a whirlwind: he went to the Philippines, where the Filipinos were resisting their new masters; he fought in China as part of an international force to suppress the Boxer Rebellion. In Latin America, he was in the U.S. invasion of Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution, guarded Panama during the digging of the canal, and eventually invaded most of the nations of Central America as well as Haiti and the Dominican Republic. And this was in just the first 20 years of his hitch.

Butler was advancing proudly racist American policies everywhere he served: Chinese, Filipinos, Central Americans and Caribbean islanders were ipso facto inferior peoples, useful as cheap labour or not at all. American investors in such countries expected the marines to protect their investments, and they did. American banks almost worked from a script: lend money to a government, wait until it has trouble repaying it, then send in the marines to oust the government and find a puppet president who will rob his country to pay the banks. (This was when the term “banana republic” first appeared.)

Katz describes Butler’s forays in Central America as rollicking adventures, young American men roaming Nicaragua and Honduras with guns and having a great old time. Butler saw a problem though: his marines were too few to police all of America’s new colonies and client states. He began to think of how to recruit local toughs and train them as “national guards.” When he got chances to implement his idea, he launched the careers of many dictators, from the Somozas of Nicaragua to Trujillo in the Dominican Republic and the Duvaliers of Haiti. As Roosevelt said of Somoza, “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

As the de facto ruler of Haiti during its first marine occupation, Butler established the detested practice of corvée — obliging Haitians to pay a tax or do unpaid labour instead. In the world’s first Black republic, which had fought a great revolution to free itself, this looked like the return of slavery. Nonetheless, it continued for years.

He also invented what we now know as counter-insurgency. Butler made friends with villagers in rebel-held areas, treating them well and exploiting their conflicts with rebels. It worked well enough in Haiti to end armed resistance, but less well in later American wars like Vietnam and Afghanistan.

Probably his worst act in Haiti was to walk into the Haitian parliament with some of his men and simply shut it down at gunpoint. It would not meet again for years, and Haiti’s continued political instability can be traced largely to that incident.

When the U.S. entered the First World War, Butler was bitterly disappointed to be left in charge of Haiti. After almost 20 years of beating up small countries, he wanted to test himself against a European enemy. But he didn’t get to Europe until the closing days of the war, and found himself in charge of a camp in France for servicemen returning to the U.S.

Katz argues that the experience may have changed Butler: He was dealing with American combat survivors, men suffering terrible physical and mental wounds. Perhaps they reminded him of his own bullet wounds and the nervous breakdown he’d had in the Philippines. Butler became their advocate, pestering the higher-ups to provide better care for returning veterans. He had always understood that his Latin American adventures had been to benefit investors and banks; now he began to wonder about the motives behind wars between empires.

‘Gruff but lovable’

Still, he remained in the service for another decade. Assigned to a new marine base in San Diego, Butler became a technical advisor for Tell It to the Marines, a 1926 Hollywood movie starring Lon Chaney. He taught Cheney how to behave like a marine, and Chaney behaved like Smedley Butler, a “gruff but lovable” guy. The movie was a big hit and created an archetype for future Hollywood war films.

By the late 1920s, Butler was back from another hitch in China, this one spent watching Japanese encroachment and clashes between Nationalists and Communists — and protecting property in Tianjin owned by Standard Oil. He also received unexpected gifts from two villages, one where his marines had rebuilt a bridge, and the other where he had kept the Nationalist army from entering and looting. Butler knew it; it was a “Boxer Village” where he’d been shot almost 20 years before while killing many of the villagers. He now gained a new respect for some of the people he’d been fighting, and new doubts about what he’d been doing with his life.

In some financial trouble as the Depression hit, Butler found he could make money as public speaker. To 700 guests at a Pittsburgh banquet, he described how he’d kept a Nicaraguan president in office by declaring opposition candidates to be bandits; then he followed up with the story about dissolving the Haitian National Assembly at gunpoint. The audience ate it up, but author Sinclair Lewis turned it into a national scandal because such outrages were still going on.

Butler’s career was dead in the water, and another speech sank it. He described how Mussolini, driving a friend of Butler’s through northern Italy, had run over and killed a child. Mussolini had dismissed the accident: “It was only one life.”

That speech got Butler a court martial, which was eventually dropped. He then retired and began a new career as a critic of U.S. policy. The Bonus Marchers arrived in Washington in the summer of 1931, veterans out of work and demanding promised back pay for their wartime service. Butler urged them to stay until their demands were met. A few days later, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered troops to attack the marchers’ shantytown.

Bizarrely, Butler was approached a few years later by people who wanted him to lead another veterans’ march on Washington — for the purpose of ousting Roosevelt and installing a new “secretary of general affairs” as dictator. The bankers behind the scheme, he was told, were torn between Butler and “a more authoritarian general: Douglas MacArthur.”

Butler blew the whistle and testified before the new House Un-American Activities Committee (which would later focus on communists only). But nothing happened. People laughed it off. As Katz observes, “Americans had been trained to react in just that way” — to laugh off real plots by those same bankers, plots which Butler had carried out with considerable force.

‘War is a racket’

In his last years Butler published a booklet, War Is a Racket, in which he saw bankers and industrialists as the racketeers. In an article for a socialist magazine, he described his career as “a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism.”

Jonathan Katz has brilliantly structured his book with chapters about his own visits to the places where Butler served, from Guantánamo to China, Haiti to the Philippines. Katz shows how those countries still live with his legacy of brutal local police and military forces, dictators and oppression. If you seek his monument, look at Duterte’s Philippines or Ortega’s Nicaragua.

Smedley Butler emerges in Katz’s book as a kind of tragic villain. An idealistic boy grown into a monster, he served his country by ruining other countries beyond repair, and eventually seeing how much harm he had done. If the Americans today fret about migrants from Central America and Haiti, or the revived hostility of China, they can now see the origin of those threats.

Canadians, too, might find in this tale a reminder that for many who are rich and powerful democracy is an OK notion until it gets in their way. Then the plotting and scheming starts. Smedley Butler was not the last racketeer for capitalism.

Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire

By Jonathan Katz

St. Martin’s Press (2022)

The life and confessions of Smedley Butler make interesting reading as schemers subvert the electoral process in the U.S., and as Canadians behold the assault on their own government by capital occupiers backed by mysterious money and tactical assistance.

Who is Smedley Butler? Once upon a time, he was America’s archetypal warrior, a U.S. Marine general who became the model for soldiers in Hollywood movies. He was literally present at the creation of the American empire, from Latin America to the Philippines — a professional toppler and installer of regimes who shaped over a century of imperial policy and administration.

Butler was even approached to lead a coup against his old friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt. For the masters of high finance who tried to recruit him for that job, democracy had become an inconvenience to be tossed away.

Today Butler is almost forgotten, an embarrassment even to the marine corps. That’s because he described his 30-year career by calling himself a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. He gave anti-war speeches on college campuses and died of cancer in 1940, the day before Hitler invaded Russia.

Jonathan Katz has resurrected Butler from 80 years of obscurity in this surprising and very well-written book. He has also explored a part of American history that Americans prefer to forget, and examined the 21st-century consequences of 19th-century presidents’ imperial ambitions.

Smedley Butler was a lucky man, born into a prosperous Philadelphia Quaker family; his father was a congressman. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Butler was only 16. Despite his age and his family’s Quaker pacifism, he was eager to help liberate Cuba from the Spanish empire. He managed to get himself into the U.S. Marines and (after very little training) shipped to Cuba as a second lieutenant. Of all places, he came ashore at Guantánamo, where he took part in some combat.

Enforcer for the banks

Then he was caught up in a whirlwind: he went to the Philippines, where the Filipinos were resisting their new masters; he fought in China as part of an international force to suppress the Boxer Rebellion. In Latin America, he was in the U.S. invasion of Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution, guarded Panama during the digging of the canal, and eventually invaded most of the nations of Central America as well as Haiti and the Dominican Republic. And this was in just the first 20 years of his hitch.

Butler was advancing proudly racist American policies everywhere he served: Chinese, Filipinos, Central Americans and Caribbean islanders were ipso facto inferior peoples, useful as cheap labour or not at all. American investors in such countries expected the marines to protect their investments, and they did. American banks almost worked from a script: lend money to a government, wait until it has trouble repaying it, then send in the marines to oust the government and find a puppet president who will rob his country to pay the banks. (This was when the term “banana republic” first appeared.)

Katz describes Butler’s forays in Central America as rollicking adventures, young American men roaming Nicaragua and Honduras with guns and having a great old time. Butler saw a problem though: his marines were too few to police all of America’s new colonies and client states. He began to think of how to recruit local toughs and train them as “national guards.” When he got chances to implement his idea, he launched the careers of many dictators, from the Somozas of Nicaragua to Trujillo in the Dominican Republic and the Duvaliers of Haiti. As Roosevelt said of Somoza, “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

As the de facto ruler of Haiti during its first marine occupation, Butler established the detested practice of corvée — obliging Haitians to pay a tax or do unpaid labour instead. In the world’s first Black republic, which had fought a great revolution to free itself, this looked like the return of slavery. Nonetheless, it continued for years.

He also invented what we now know as counter-insurgency. Butler made friends with villagers in rebel-held areas, treating them well and exploiting their conflicts with rebels. It worked well enough in Haiti to end armed resistance, but less well in later American wars like Vietnam and Afghanistan.

Probably his worst act in Haiti was to walk into the Haitian parliament with some of his men and simply shut it down at gunpoint. It would not meet again for years, and Haiti’s continued political instability can be traced largely to that incident.

When the U.S. entered the First World War, Butler was bitterly disappointed to be left in charge of Haiti. After almost 20 years of beating up small countries, he wanted to test himself against a European enemy. But he didn’t get to Europe until the closing days of the war, and found himself in charge of a camp in France for servicemen returning to the U.S.

Katz argues that the experience may have changed Butler: He was dealing with American combat survivors, men suffering terrible physical and mental wounds. Perhaps they reminded him of his own bullet wounds and the nervous breakdown he’d had in the Philippines. Butler became their advocate, pestering the higher-ups to provide better care for returning veterans. He had always understood that his Latin American adventures had been to benefit investors and banks; now he began to wonder about the motives behind wars between empires.

‘Gruff but lovable’

Still, he remained in the service for another decade. Assigned to a new marine base in San Diego, Butler became a technical advisor for Tell It to the Marines, a 1926 Hollywood movie starring Lon Chaney. He taught Cheney how to behave like a marine, and Chaney behaved like Smedley Butler, a “gruff but lovable” guy. The movie was a big hit and created an archetype for future Hollywood war films.

By the late 1920s, Butler was back from another hitch in China, this one spent watching Japanese encroachment and clashes between Nationalists and Communists — and protecting property in Tianjin owned by Standard Oil. He also received unexpected gifts from two villages, one where his marines had rebuilt a bridge, and the other where he had kept the Nationalist army from entering and looting. Butler knew it; it was a “Boxer Village” where he’d been shot almost 20 years before while killing many of the villagers. He now gained a new respect for some of the people he’d been fighting, and new doubts about what he’d been doing with his life.

In some financial trouble as the Depression hit, Butler found he could make money as public speaker. To 700 guests at a Pittsburgh banquet, he described how he’d kept a Nicaraguan president in office by declaring opposition candidates to be bandits; then he followed up with the story about dissolving the Haitian National Assembly at gunpoint. The audience ate it up, but author Sinclair Lewis turned it into a national scandal because such outrages were still going on.

Butler’s career was dead in the water, and another speech sank it. He described how Mussolini, driving a friend of Butler’s through northern Italy, had run over and killed a child. Mussolini had dismissed the accident: “It was only one life.”

That speech got Butler a court martial, which was eventually dropped. He then retired and began a new career as a critic of U.S. policy. The Bonus Marchers arrived in Washington in the summer of 1931, veterans out of work and demanding promised back pay for their wartime service. Butler urged them to stay until their demands were met. A few days later, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered troops to attack the marchers’ shantytown.

Bizarrely, Butler was approached a few years later by people who wanted him to lead another veterans’ march on Washington — for the purpose of ousting Roosevelt and installing a new “secretary of general affairs” as dictator. The bankers behind the scheme, he was told, were torn between Butler and “a more authoritarian general: Douglas MacArthur.”

Butler blew the whistle and testified before the new House Un-American Activities Committee (which would later focus on communists only). But nothing happened. People laughed it off. As Katz observes, “Americans had been trained to react in just that way” — to laugh off real plots by those same bankers, plots which Butler had carried out with considerable force.

‘War is a racket’

In his last years Butler published a booklet, War Is a Racket, in which he saw bankers and industrialists as the racketeers. In an article for a socialist magazine, he described his career as “a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism.”

Jonathan Katz has brilliantly structured his book with chapters about his own visits to the places where Butler served, from Guantánamo to China, Haiti to the Philippines. Katz shows how those countries still live with his legacy of brutal local police and military forces, dictators and oppression. If you seek his monument, look at Duterte’s Philippines or Ortega’s Nicaragua.

Smedley Butler emerges in Katz’s book as a kind of tragic villain. An idealistic boy grown into a monster, he served his country by ruining other countries beyond repair, and eventually seeing how much harm he had done. If the Americans today fret about migrants from Central America and Haiti, or the revived hostility of China, they can now see the origin of those threats.

Canadians, too, might find in this tale a reminder that for many who are rich and powerful democracy is an OK notion until it gets in their way. Then the plotting and scheming starts. Smedley Butler was not the last racketeer for capitalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment