Mark Zuckerberg’s dream of a harmonious online community faces a test

Updated: 22 Feb 2022

Parmy Olson

Virtual worlds must assure everyone safety at their very inception

When Mark Zuckerberg described the metaverse last year, he conjured an image of harmonious social connections in an immersive virtual world. But his company’s first iterations of the space have not been very harmonious. Several women have reported incidents of harassment, including a beta tester who was virtually groped by a stranger and another who was virtually gang-raped within 60 seconds of entering Facebook’s Horizon Venues platform, as alleged. I had several uncomfortable moments with male strangers on social apps run by both Meta and Microsoft in December.

These are early days for the metaverse, but that’s the problem. If safety isn’t baked early on into its design, it’ll be much harder to secure down the line. Gaming firms like Riot Games, for instance, have faced an uphill battle trying to rescue a virtual community from toxic behaviour. Facebook also knows this problem well: It struggled to put the proverbial toothpaste back in the tube with covid vaccine misinformation, as highlighted by a whistleblower last year.

Virtual worlds must assure everyone safety at their very inception

When Mark Zuckerberg described the metaverse last year, he conjured an image of harmonious social connections in an immersive virtual world. But his company’s first iterations of the space have not been very harmonious. Several women have reported incidents of harassment, including a beta tester who was virtually groped by a stranger and another who was virtually gang-raped within 60 seconds of entering Facebook’s Horizon Venues platform, as alleged. I had several uncomfortable moments with male strangers on social apps run by both Meta and Microsoft in December.

These are early days for the metaverse, but that’s the problem. If safety isn’t baked early on into its design, it’ll be much harder to secure down the line. Gaming firms like Riot Games, for instance, have faced an uphill battle trying to rescue a virtual community from toxic behaviour. Facebook also knows this problem well: It struggled to put the proverbial toothpaste back in the tube with covid vaccine misinformation, as highlighted by a whistleblower last year.

Mark Zuckerberg’s control of Facebook is unlikely to reduce

Nick Clegg appointed president of global affairs at Meta

It turns out Facebook has grappled internally with building safety features into its new metaverse services. In 2016, it released Oculus Rooms, an app where anyone with its headset could hang out in a virtual apartment with friends and family. In 2017, it built Oculus Venues (now Horizon Venues), a virtual space where it would show films or sports games in the hope that visitors would mingle and make connections. It was a big shift, but also open to new risks.

The firm began holding meetings to discuss how they might design safety features into Venues, recalls Jim Purbrick, a former engineering manager at Facebook involved with its VR efforts, which they hadn’t done when designing Rooms. Managers did pay attention to safety, he tells me. For instance, people had to watch a safety video before entering Venues. He says he warned engineers early on that VR avatars should fade out and disappear if they got too close to another user. They liked the idea, he says, but it was never implemented. A spokeswoman for Facebook didn’t say why the firm had not implemented a fade-to-vanish feature, and instead highlighted its new ‘personal boundary’ tool, which prevents certain avatars from coming within a radius of two virtual feet of your own.

The boundary tool can backfire, Purbrick says, pointing to how similar features have been misused in gaming. “You can end up with gangs of people creating rings around others, making it difficult for them to move out," he says. “If there’s a big crowd and you have a bunch of personal boundaries, it makes navigation harder." Meta said avatars would still be able to move forward with the boundary tool.“Oculus definitely cared about people having good experiences in VR and understood that a bad first experience could put people off VR forever, but I think they underestimated the size of the problem," Purbrick adds.

He believes Meta should make safety features easier to find, like a fire extinguisher, and get volunteers to monitor behaviour. The gaming industry has some templates for this sort of governance. Until now, Meta has centralized the task of moderating content on Facebook, but it will struggle with such an approach in a new virtual world.

The company has “the most centralized decision-making structure" ever for a large company, according to one early backer, a description underscored by Zuckerberg’s control of 57% of the company’s voting shares. But virtual worlds are human communities at their core, which means people will want more of a say in how they are run. Relinquishing some of that central control could help Meta mitigate harassment.

Educating visitors about what constitutes potentially criminal behaviour would, too. Holly Powell Jones, a criminologist, has found that an alarming number of children and teenagers shrug off harassment or the sharing of indecent images because they have no idea that they are criminal offences. People have “almost certainly" been harassed at a criminal level in virtual reality already, she says. “Harassment in digital spaces is nothing new, and it’s something we and others in the industry have been working to address for years," Meta’s spokeswoman said.

With the police already stretched from social-media cases and the offline world, tech firms should try more radical solutions to address harassment in the metaverse before it’s too late. The dearth of women in the development process for virtual reality certainly isn’t helping and could be fixed.

Microsoft last week announced a more drastic move to combat harassment: It was shutting down several of its social platforms, including Campfire, muting all attendees when they joined an event and activating ‘safety bubbles’ as a default. Meta should take a cue from that. Else, its metaverse dream may fade away.

Parmy Olson is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology.

Meta is down $500 billion since changing its name from Facebook

No longer a top ten company

By Rob Thubron

In context: Mark Zuckerberg has really gone all-in on the metaverse. So convinced is the CEO that virtual, shared worlds are the future of tech, he changed Facebook’s corporate name to Meta last year. But what has happened since that rebranding? The company has seen $500 billion wiped off its market value.

New York Mag reports that Meta’s half-a-trillion-dollar decline since the rebranding has resulted in a drop from its lofty position as the sixth-largest company in the world by market capitalization to 11th position, replaced by the likes of Nvidia and Tencent.

A lot of Meta’s problems don’t stem from the new name but are a result of Apple’s privacy changes introduced in iOS 14 that allow users to opt out of targeted ads and prevent apps from tracking cross-app behavior. Meta said the change would put a $10 billion dent in its ad revenue this year—an announcement that wiped $232 billion off its market cap in a single day.

Google is introducing similar privacy measures with its Privacy Sandbox for Android, though its implementation isn’t as extreme as Apple’s, and it won’t arrive for at least two years.

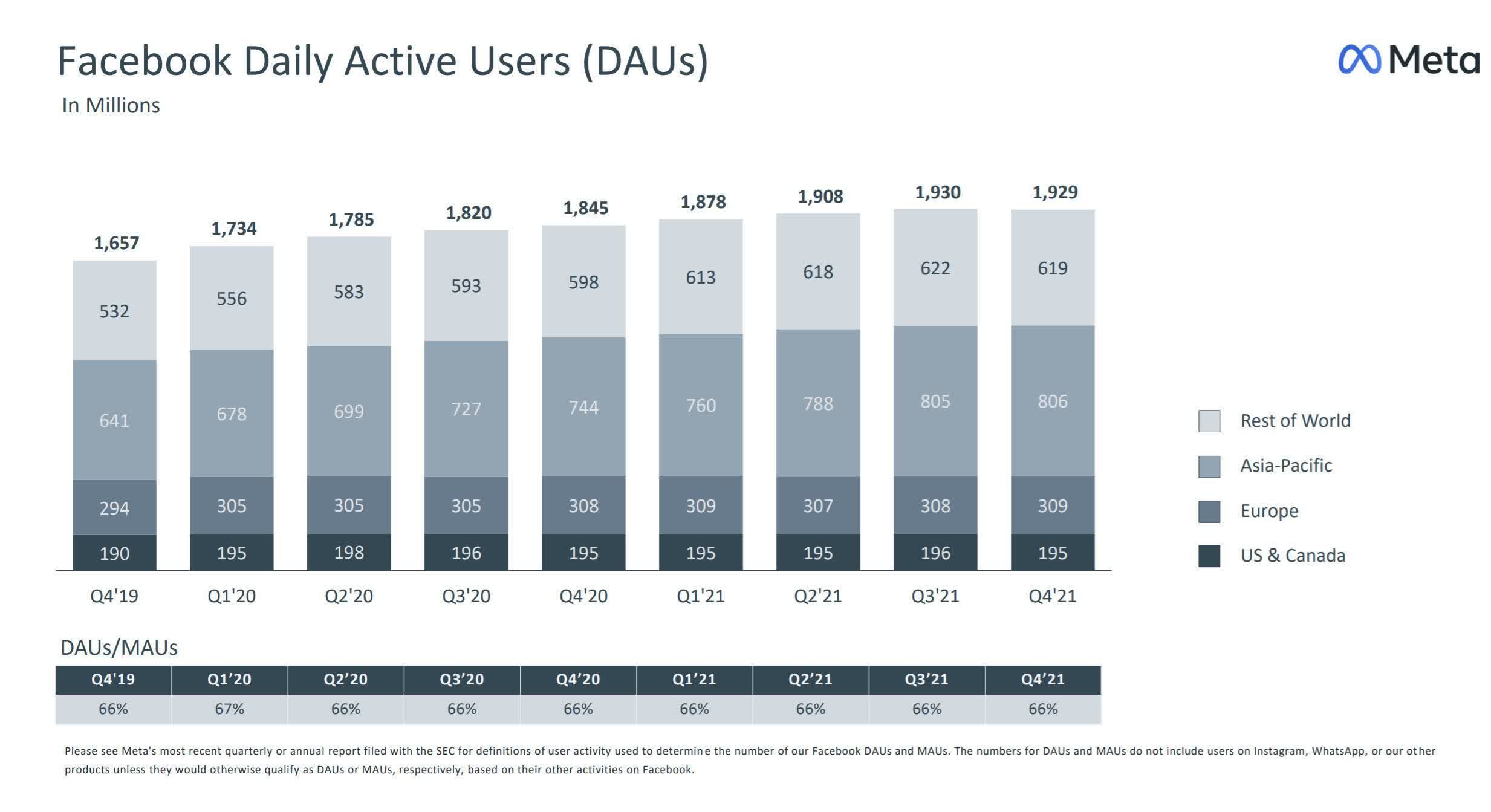

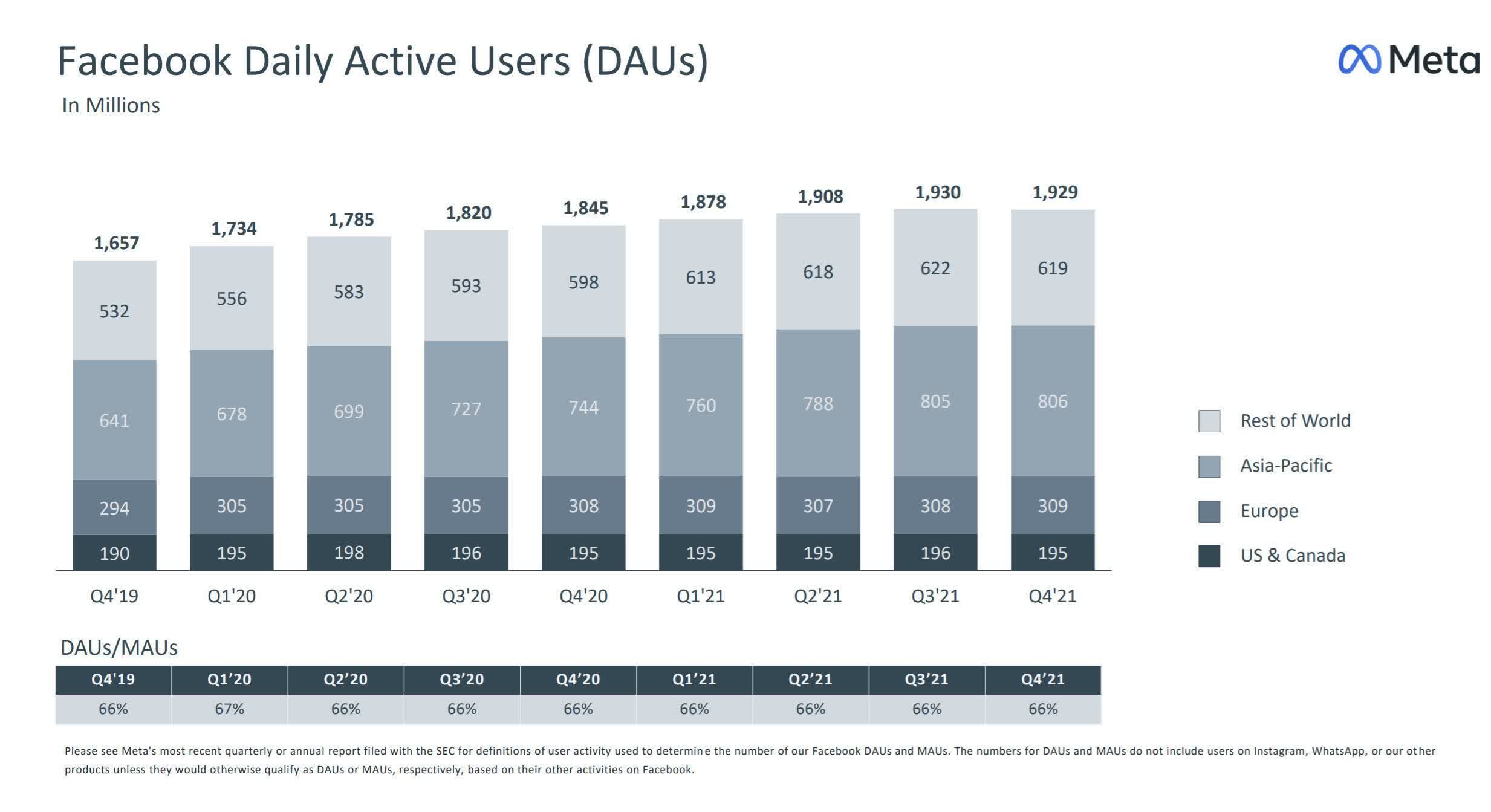

Then there’s Facebook. The social media platform had an unwelcome sight in its most recent earnings report: the fourth quarter saw its daily user numbers decline for the first time, plunging its share price 20%. Moreover, the AR and VR division (Reality Labs), an important part of its metaverse plans, made a $10.2 billion loss in 2021.

Another problem for Meta is that while many companies are looking to jump onto the metaverse idea, most consumers are apathetic towards what some consider a VR version of Second Life. The metaverse, Web 3.0, and NFTs might excite firms looking to capitalize on them, but the buzzwords leave many people apathetic at best, hostile at worst—a patent hinting at metaverse eye-tracking ad tech certainly hasn’t helped.

Meta still has a market cap of $561 billion. It made $33.76 billion in revenue during Q4, up 20% year-on-year, and the overall number of daily active users across all its apps grew slightly, so it certainly isn’t in trouble. But maybe the metaverse, at least Meta’s interpretation of it, isn’t going to be as revolutionary as Zuckerberg thinks.

Related Reads

In context: Mark Zuckerberg has really gone all-in on the metaverse. So convinced is the CEO that virtual, shared worlds are the future of tech, he changed Facebook’s corporate name to Meta last year. But what has happened since that rebranding? The company has seen $500 billion wiped off its market value.

New York Mag reports that Meta’s half-a-trillion-dollar decline since the rebranding has resulted in a drop from its lofty position as the sixth-largest company in the world by market capitalization to 11th position, replaced by the likes of Nvidia and Tencent.

A lot of Meta’s problems don’t stem from the new name but are a result of Apple’s privacy changes introduced in iOS 14 that allow users to opt out of targeted ads and prevent apps from tracking cross-app behavior. Meta said the change would put a $10 billion dent in its ad revenue this year—an announcement that wiped $232 billion off its market cap in a single day.

Google is introducing similar privacy measures with its Privacy Sandbox for Android, though its implementation isn’t as extreme as Apple’s, and it won’t arrive for at least two years.

Then there’s Facebook. The social media platform had an unwelcome sight in its most recent earnings report: the fourth quarter saw its daily user numbers decline for the first time, plunging its share price 20%. Moreover, the AR and VR division (Reality Labs), an important part of its metaverse plans, made a $10.2 billion loss in 2021.

Another problem for Meta is that while many companies are looking to jump onto the metaverse idea, most consumers are apathetic towards what some consider a VR version of Second Life. The metaverse, Web 3.0, and NFTs might excite firms looking to capitalize on them, but the buzzwords leave many people apathetic at best, hostile at worst—a patent hinting at metaverse eye-tracking ad tech certainly hasn’t helped.

Meta still has a market cap of $561 billion. It made $33.76 billion in revenue during Q4, up 20% year-on-year, and the overall number of daily active users across all its apps grew slightly, so it certainly isn’t in trouble. But maybe the metaverse, at least Meta’s interpretation of it, isn’t going to be as revolutionary as Zuckerberg thinks.

Related Reads

No comments:

Post a Comment