James T. Keane

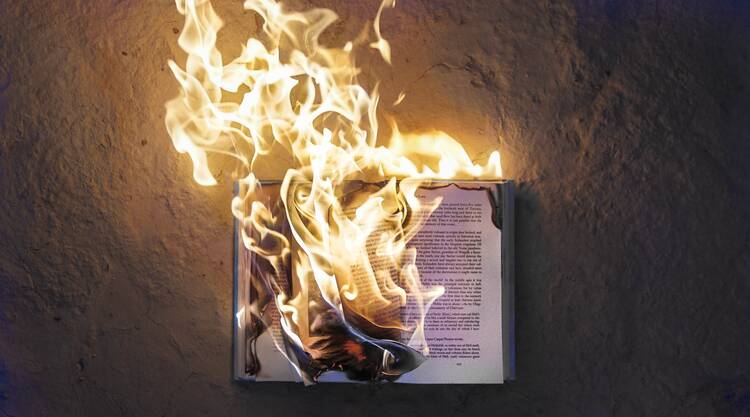

Photo by Freddy Kearney on Unsplash

Banned! The news last week that Art Spiegelman’s 1986 graphic novel about the Holocaust, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, had been removed from school curricula by a Tennessee school board (for obscenity and nudity, the latter of which involved not humans but…mice) was a reminder of one of our nation’s favorite pastimes: book bans. The American Library Association reports it received an unprecedented 330 reports of “book challenges” last fall, usually involving books that deal with issues that are flashpoints in national cultural battles: sex, gender identity and social mores. The move will likely backfire—it almost always does—and Maus is already climbing the ranks of the best-seller lists, 36 years after its publication.

Banned! The news last week that Art Spiegelman’s 1986 graphic novel about the Holocaust, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, had been removed from school curricula by a Tennessee school board (for obscenity and nudity, the latter of which involved not humans but…mice) was a reminder of one of our nation’s favorite pastimes: book bans. The American Library Association reports it received an unprecedented 330 reports of “book challenges” last fall, usually involving books that deal with issues that are flashpoints in national cultural battles: sex, gender identity and social mores. The move will likely backfire—it almost always does—and Maus is already climbing the ranks of the best-seller lists, 36 years after its publication.

The news that Maus, a graphic novel about the Holocaust, had been removed from school curricula by a Tennessee school board was a reminder of one of our nation’s favorite pastimes: book bans.

One of the most famous novels to be banned in the United States was James Joyce’s Ulysses, which for almost 12 years after its publication in 1922 was outlawed in the United States. When the ban was finally lifted in December 1933, one strong objector to its publication was America’s literary editor at the time (and the editor in chief from 1936 to 1944), Francis X. Talbot, S.J. Despite what would otherwise appear somewhat cosmopolitan literary tastes for a priest at the time, Talbot detested Joyce, and made his feelings clear in a 1934 essay in the magazine:

The book was written in a new technique, in a pseudo-English, of words that were sometimes normal, sometimes foreign, sometimes archaic, sometimes merely a succession of letters, meaningless and inane. Many of the words were scummy, scrofulous, putrid, like excrement of the mind. The words are listed in the dictionary, but never in the writings or on the tongue of anyone except the insane, or the lowest human dregs. The critics said how brave. The sexual neurotics said how lovely. The normal person said I'm sick.

Ultimately, Talbot said, Joyce would not be a topic of discussion for long, because the book was not of a quality that would merit it any audience outside of those simply looking to be titillated or amused. “Only a person who had been a Catholic, only one with an incurably diseased mind, could be so diabolically venomous toward God, toward the Blessed Sacrament, toward the Virgin Mary. But the case of ‘Ulysses’ is closed,” he wrote. “All the curiosity caused by the extraneous circumstances of its being banned is over. It has now subsided into just a book. It will be discussed, undoubtedly, in the little literary pools of amateurs and young Catholic radicals. But for the most part it is in the grave, odorously.”

Well, Father Talbot may have been wrong about the book’s lasting influence, but no one could question his verve. I suspect Joyce would rather like him if they had ever met. But it is a dangerous thing to argue for the banning of a book, because in the end the mob can be somewhat indiscriminate in whom they come for. Maus was ostensibly banned for the same reason as Ulysses—a vague notion that it was obscene—but what if the real motivation was that it is about the Holocaust?

One could gin up a dozen reasons in half a minute to ban almost everything we read in school: Huckleberry Finn is racist, as are C. S. Lewis’s Narnia novels. Dr. Suess is this close to being canceled; Judy Blume is a regular on the list of books parents clutch their pearls over when they are found in the school library. But isn’t it O.K., every now and then, for our children to read something unsettling?

This issue raised its head at, of all places, Duke University in 2015, when students and parents complained that the required reading for incoming freshmen, Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home, was pornographic and promoted alternative lifestyles. I wrote about the kerfuffle in America at the time (It amounted to nothing; students afraid they would be scandalized by the book were allowed to opt out), and thought back to the church’s long history of book banning itself.

“Our irony, in the world of Catholic literature and academia, is that no group should fear the good intentions of the censors more than Catholic intellectuals themselves,” I wrote then. “It wasn’t long ago that Rome was actually blacklisting Graham Greene and other novelists in the Index of Forbidden Books, to say nothing of the academic theologians silenced by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Why? Because good Catholics needed to be protected from harmful literature.

“Laughable, isn’t it? That we once thought so little of people that we assumed they’d be permanently damaged if they read the wrong thing.”

One could gin up a dozen reasons in half a minute to ban almost everything we read in school.

•••

James T. Keane is a senior editor at America.

A JESUIT JOURNAL

No comments:

Post a Comment