Posted byTonia Nissen

6 February 2022

The world’s first cloned black-footed ferret just celebrated her one birthday and has reached the breeding age. Elizabeth Ann is on the verge of making history.

And, if she is thriving and has healthy offspring, the small predator will provide a vital boost to efforts to conserve her critically endangered species.

Scientists admit, however, that they will have to be exceedingly cautious when screening potential mates for Elizabeth Ann, who is being held at a conservation center outside Fort Collins, Colorado.

They believe that the man they finally choose must have one crucial attribute in particular: he must be gentle.

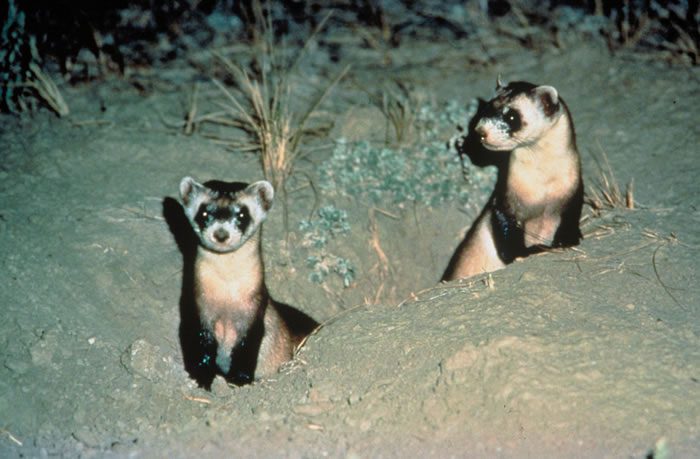

The black-footed ferret (Mustella nigripes) is not recognized for having a pleasant disposition.

Elizabeth Ann, for example, snarls at caretakers who go too near.

The world’s first cloned black-footed ferret just celebrated her one birthday and has reached the breeding age. Elizabeth Ann is on the verge of making history.

And, if she is thriving and has healthy offspring, the small predator will provide a vital boost to efforts to conserve her critically endangered species.

Scientists admit, however, that they will have to be exceedingly cautious when screening potential mates for Elizabeth Ann, who is being held at a conservation center outside Fort Collins, Colorado.

They believe that the man they finally choose must have one crucial attribute in particular: he must be gentle.

The black-footed ferret (Mustella nigripes) is not recognized for having a pleasant disposition.

Elizabeth Ann, for example, snarls at caretakers who go too near.

Credit: The Guardian

However, according to experts, the species is in critical need of new DNA, which Elizabeth Ann may offer, as long as she survives the breeding encounter.

Oliver Ryder, director of genetics conservation at San Diego Zoo, told the Observer that:

“When it comes to black-footed ferrets, the mating scenario can get a little rough and we don’t want Elizabeth Ann to be injured. She is precious. So we need an experienced male who has already produced offspring and who is therefore not going to be infertile – a problem that affects many black-footed ferret males today. In addition, we will select him for his gentleness.”

Ryder added that selecting a mate for Elizabeth Ann was now “imminent.”

The black-footed ferret is a grumpy predator with black markings on its face, paws, and tail, 60cm in length.

It originally roamed vast swaths of the United States’ Great Plains, subsisting primarily on prairie dogs, a kind of ground squirrel.

Thought To be Extinct For a Long TIme

However, it was wiped off as farming grew over the central United States, and it was assumed to be extinct by the 1970s.

Then, one night in 1981, John Hogg, a rancher in Wyoming, heard weird sounds on his property and discovered a colony of black-footed ferrets.

However, according to experts, the species is in critical need of new DNA, which Elizabeth Ann may offer, as long as she survives the breeding encounter.

Oliver Ryder, director of genetics conservation at San Diego Zoo, told the Observer that:

“When it comes to black-footed ferrets, the mating scenario can get a little rough and we don’t want Elizabeth Ann to be injured. She is precious. So we need an experienced male who has already produced offspring and who is therefore not going to be infertile – a problem that affects many black-footed ferret males today. In addition, we will select him for his gentleness.”

Ryder added that selecting a mate for Elizabeth Ann was now “imminent.”

The black-footed ferret is a grumpy predator with black markings on its face, paws, and tail, 60cm in length.

It originally roamed vast swaths of the United States’ Great Plains, subsisting primarily on prairie dogs, a kind of ground squirrel.

Thought To be Extinct For a Long TIme

However, it was wiped off as farming grew over the central United States, and it was assumed to be extinct by the 1970s.

Then, one night in 1981, John Hogg, a rancher in Wyoming, heard weird sounds on his property and discovered a colony of black-footed ferrets.

Credit: New Hampshire PBS

Wildlife scientists rushed to the ranch, and it has since been utilized to build a ferret breeding program to re-establish colonies throughout the United States.

Only seven of the ferrets discovered on Hogg Ranch were able to reproduce.

Consequently, the black-foot population is strongly inbred, with each animal having kinship with the others that falls between that of a sibling and that of a first cousin.

Mutations are now wreaking havoc on the breeding population.

Elizabeth Ann can deliver an influx of new ferret genes, which is much required.

She is the result of tissue extracted decades ago from a female black-footed ferret named Willa.

Her cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen at San Diego’s Frozen Zoo, which stores genetic resources from endangered species, such as DNA, sperm, eggs, embryos, and living tissue.

It was determined a few years ago to utilize the same technique used in Scotland to make Dolly the Sheep in 1996 to develop a clone of Willa.

Her cells were used to create embryos, then implanted into three female domestic ferrets.

Two of the pregnancies failed, while the third surrogate mother produced one stillborn child… and Elizabeth Ann, who is now flourishing in her Colorado home on a diet of hamsters.

Her DNA, however, has distinct versions of the genes that predominate in the breeding program’s inbred ferrets, raising hopes that her children may considerably increase the genetic viability of black-footed ferrets.

Elizabeth Ann is a treasure trove of genetic diversity as far as we are concerned,” Ryder says.

In addition, plans are in the works to produce another batch of cloned black-footed ferrets with the same goal in mind: to increase the species’ genetic variety and reverse its reproductive decline.

“That’s the crux of the effort here,” said Ryder. “Can Elizabeth Ann pass along her genes to descendant generations of black-footed ferrets?”

Ryder went on to say that Elizabeth Ann’s tale has far-reaching consequences for all endangered animals.

Ryder added that we should be storing cells from all kinds of endangered species right now because we’re losing biodiversity, and wild animal gene pools are diminishing.

At the very least, if we have the cells, we may accomplish for other species what we want to achieve for the black-footed ferret with Elizabeth Ann in the future.

Wildlife scientists rushed to the ranch, and it has since been utilized to build a ferret breeding program to re-establish colonies throughout the United States.

Only seven of the ferrets discovered on Hogg Ranch were able to reproduce.

Consequently, the black-foot population is strongly inbred, with each animal having kinship with the others that falls between that of a sibling and that of a first cousin.

Mutations are now wreaking havoc on the breeding population.

Elizabeth Ann can deliver an influx of new ferret genes, which is much required.

She is the result of tissue extracted decades ago from a female black-footed ferret named Willa.

Her cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen at San Diego’s Frozen Zoo, which stores genetic resources from endangered species, such as DNA, sperm, eggs, embryos, and living tissue.

It was determined a few years ago to utilize the same technique used in Scotland to make Dolly the Sheep in 1996 to develop a clone of Willa.

Her cells were used to create embryos, then implanted into three female domestic ferrets.

Two of the pregnancies failed, while the third surrogate mother produced one stillborn child… and Elizabeth Ann, who is now flourishing in her Colorado home on a diet of hamsters.

Her DNA, however, has distinct versions of the genes that predominate in the breeding program’s inbred ferrets, raising hopes that her children may considerably increase the genetic viability of black-footed ferrets.

Elizabeth Ann is a treasure trove of genetic diversity as far as we are concerned,” Ryder says.

In addition, plans are in the works to produce another batch of cloned black-footed ferrets with the same goal in mind: to increase the species’ genetic variety and reverse its reproductive decline.

“That’s the crux of the effort here,” said Ryder. “Can Elizabeth Ann pass along her genes to descendant generations of black-footed ferrets?”

Ryder went on to say that Elizabeth Ann’s tale has far-reaching consequences for all endangered animals.

Ryder added that we should be storing cells from all kinds of endangered species right now because we’re losing biodiversity, and wild animal gene pools are diminishing.

At the very least, if we have the cells, we may accomplish for other species what we want to achieve for the black-footed ferret with Elizabeth Ann in the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment