Women workers experienced more verbal, physical and sexual violence under COVID-19, reveals report into garment factories in six Asian countries

Tansy Hoskins

18 February 2022

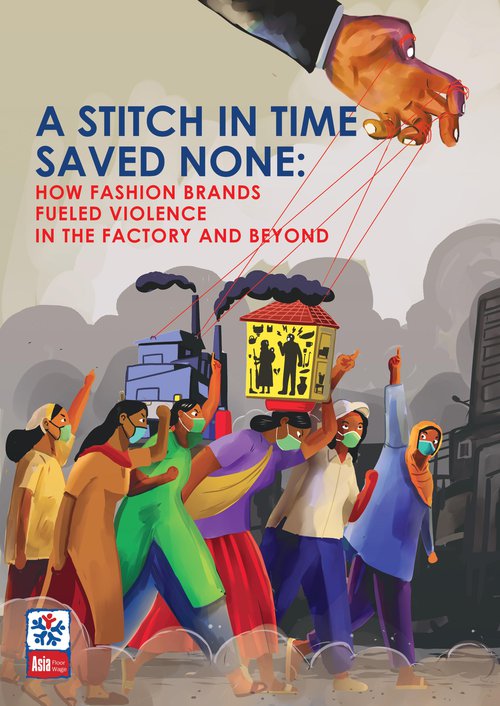

Illustration: Inge Snip. All rights reserved

“Any mother who sends their daughter to a factory will be scared for her safety. I have worked in this industry for more than 20 years and I have seen terrible things happen: rapes, suicides and even murders,” said Chellamma*, a 46-year-old garment worker in the city of Tiruppur in Tamil Nadu.

Tiruppur, which is known as the knitwear capital of India, bustles with garment factories, but when her two daughters started looking for work, Chellamma insisted it was in the same factory as her, so that she could at least try to keep them safe.

“Women workers have no power to oppose the men in power – be it supervisors or managers. They can do anything to any woman, we are all at their mercy and we have no one to support or stand for us,” she said.

Women at the factory where Chellamma and her daughters work were interviewed as part of a new in-depth survey that documents an alarming rise in Gender Based Violence and Harassment (GBVH) against garment workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. It examined six countries: Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

‘A Stitch in Time Saves None’, by the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA), says that while the global garment industry has promised to reduce poverty and uplift the status of women, in reality it has delivered rock-bottom wages, extreme hours and unsafe, often violent conditions. As a result, the AFWA now terms the harm inflicted on garment workers as the “Garment Industrial Trauma Complex”.

The report, which makes for extremely disturbing reading, directly links the rise in GVBH during the pandemic to the purchasing practices of international fashion brands including American Eagle, Bestseller, C&A, Inditex, Kohl’s, Levi’s, Marks & Spencer, Next, Nike, Target, Vans/VF Corporation and Walmart.

“GBVH, in the form of economic harm, has become an essential condition in supply chains through which lead firms transfer the costs of market crises to women workers in order to accumulate vast profits or control losses,” according to the report. Workers are paid poverty-level wages, which means they can’t survive even a few days without work and quickly fall into hunger, debt and intergenerational poverty.

"We have documented violence from men including supervisors, landlords, dormitory owners, shop keepers etc – men in positions of power who used the pandemic to further exploit and abuse women,” explained Ashley Saxby, South-East Asia coordinator at AFWA.

“This is linked to a range of gendered power dynamics, but it can’t be separated from the purchasing practices of brands and their actions during the pandemic that reinforced women’s vulnerability."

Verbal, physical and sexual violence

When the owners of Chellamma’s factory resumed production after the first lockdown in 2020, workers experienced extra overtime (unpaid), high targets and an increase in GBVH.

Another worker at the factory, Soumya, described verbal harassment as part of the job. “As production targets increase, harassment also increases. Every day is stressful,” she said. “Some supervisors call you ‘bitch’, ‘moron’, ‘idiot’ and so on, when a worker does not finish targets. Complaints against all this won’t take you anywhere. No one cares about our complaints. Only finishing production targets matter.”

AFWA's report into garment factories in Asia | AFWA

At a factory in Gurgaon in northern India, workers reported being pushed, touched inappropriately, having items of clothing thrown at them, and supervisors repeatedly raising their hands as if to slap them. An elderly woman from the factory said: “What respect will you have for men who abuse women of their mother’s age?”

As well as verbal and physical abuse, workers reported sexual violence. “The supervisor harassed me in various ways, even trying to touch my body, slapping me on my backside,” said Sakhina, a worker in the busy garment city of Gazipur in Bangladesh. “One day he hugged me when he found me alone in front of the toilet. After that, I was afraid to go to the toilet.”

I kept silent for fear of losing my job

Increased job insecurity during the pandemic led to an increased fear of retaliation if violence was reported. This created an even greater culture of impunity among male supervisors. “Despite these problems,” Sakhina said, “I kept silent for fear of losing my job.”

At other factories there were reports of women workers being coerced into sex by factory mechanics who otherwise refused to fix broken sewing machine, which meant that workers lost vital wages.

Impact on home life

The impact of brands’ purchasing practises did not remain within factory walls, but ricocheted out into workers’ homes and communities. The report outlines how, during the COVID-19 pandemic, workers faced “not only the retreat of the state but also the disengagement of global apparel brands and the absence of employer-based social protection”.

According to the report, factory life is inseparable from home life, where women garment workers do the majority of the housework and care provision: “The fashion industry, despite being a modern capitalist industry, relies on and strengthens pre-capitalist patriarchal relations in supplier countries as a central means to amass wealth.”

For many people around the world, the pandemic deepened the significance of the home, but for many garment workers, ‘home’ was reinforced as a site of violence.

Sonali is a 40-year-old garment worker from Bengaluru (Bangalore) in India. Her lockdown experience was one of closed factories, nothing to eat except rice and water, and not enough money to buy medicine for her daughter. But there is another part of her story.

“Although I am separated from my husband, I had to live with him during the lockdown period because I did not have any savings,” she said. “My husband tried to sexually abuse me many times. He would not take a ‘no’ as an answer. It was torture. I have never felt so helpless in my life. Many women had to endure this [marital rape] silently during the lockdown.”

Sonali’s experience is inseparable from her treatment as a worker for global fashion brands. Her pay is so low that she is unable to amass any savings for periods of crisis, such as the pandemic.

“The shame associated with speaking about her experience, and living in a highly patriarchal society, prevented Sonali from speaking out,” said Nandita Shivakumar, AFWA’s campaigns and communications coordinator.

“When we do these interviews, we also offer GBVH training and a safe space where many women speak about their personal lives – that is why women like Sonali open up about these issues. Many feel that if they had higher wages, they could leave abusive marriages,” Shivakumar explained.

Anju is another worker in Gazipur, Bangladesh. Her story represents the widespread increase in gender-based violence by landlords and dormitory owners within the fashion industry. “When the pandemic came, my work became irregular and I couldn’t pay my rent on time,” she said.

“After two months, my landlord approached me and said, spend two nights with me and I will not charge you for the rent. Make me happy and I will help you. With that, I thought my only [way] out was suicide.” When she refused him, the landlord stole her jewellery and kicked Anju out of her home. Other garment workers report similar stories of harassment and violence from shopkeepers, to whom they have fallen into debt.

Pay a living wage

“The lack of living wages escalated the massive humanitarian crisis brought about by the pandemic,” according to ‘A Stitch in Time’, so it is not surprising that a living wage is the first thing AFWA is calling for.

“Preventing and remediating gender-based violence in homes and factories requires brands to provide living wages for workers and ending all barriers to freedom of association and collective bargaining – especially in women-dominated sectors from the garment industry,” said Saxby.

AFWA also wants to see its ‘Safe Circle Approach’ established across factories. This includes pouring time and resources into building women workers’ leadership on production lines; ending misogynistic power relations between owners and workers; and long-term monitoring and oversight. AFWA says that brands must stop exploiting governance weaknesses and patriarchal social norms in production countries in their quest for profit.

“Vague, superficial and noncommittal promises of brands to eradicate gender-based violence need to be replaced with enforceable, binding commitments to work with women-led trade unions, to develop agreements and programmes to monitor, remediate and prevent GBVH,” Saxby concludes.

* The names of all garment workers have been changed.

At a factory in Gurgaon in northern India, workers reported being pushed, touched inappropriately, having items of clothing thrown at them, and supervisors repeatedly raising their hands as if to slap them. An elderly woman from the factory said: “What respect will you have for men who abuse women of their mother’s age?”

As well as verbal and physical abuse, workers reported sexual violence. “The supervisor harassed me in various ways, even trying to touch my body, slapping me on my backside,” said Sakhina, a worker in the busy garment city of Gazipur in Bangladesh. “One day he hugged me when he found me alone in front of the toilet. After that, I was afraid to go to the toilet.”

I kept silent for fear of losing my job

Increased job insecurity during the pandemic led to an increased fear of retaliation if violence was reported. This created an even greater culture of impunity among male supervisors. “Despite these problems,” Sakhina said, “I kept silent for fear of losing my job.”

At other factories there were reports of women workers being coerced into sex by factory mechanics who otherwise refused to fix broken sewing machine, which meant that workers lost vital wages.

Impact on home life

The impact of brands’ purchasing practises did not remain within factory walls, but ricocheted out into workers’ homes and communities. The report outlines how, during the COVID-19 pandemic, workers faced “not only the retreat of the state but also the disengagement of global apparel brands and the absence of employer-based social protection”.

According to the report, factory life is inseparable from home life, where women garment workers do the majority of the housework and care provision: “The fashion industry, despite being a modern capitalist industry, relies on and strengthens pre-capitalist patriarchal relations in supplier countries as a central means to amass wealth.”

For many people around the world, the pandemic deepened the significance of the home, but for many garment workers, ‘home’ was reinforced as a site of violence.

Sonali is a 40-year-old garment worker from Bengaluru (Bangalore) in India. Her lockdown experience was one of closed factories, nothing to eat except rice and water, and not enough money to buy medicine for her daughter. But there is another part of her story.

“Although I am separated from my husband, I had to live with him during the lockdown period because I did not have any savings,” she said. “My husband tried to sexually abuse me many times. He would not take a ‘no’ as an answer. It was torture. I have never felt so helpless in my life. Many women had to endure this [marital rape] silently during the lockdown.”

Sonali’s experience is inseparable from her treatment as a worker for global fashion brands. Her pay is so low that she is unable to amass any savings for periods of crisis, such as the pandemic.

“The shame associated with speaking about her experience, and living in a highly patriarchal society, prevented Sonali from speaking out,” said Nandita Shivakumar, AFWA’s campaigns and communications coordinator.

“When we do these interviews, we also offer GBVH training and a safe space where many women speak about their personal lives – that is why women like Sonali open up about these issues. Many feel that if they had higher wages, they could leave abusive marriages,” Shivakumar explained.

Anju is another worker in Gazipur, Bangladesh. Her story represents the widespread increase in gender-based violence by landlords and dormitory owners within the fashion industry. “When the pandemic came, my work became irregular and I couldn’t pay my rent on time,” she said.

“After two months, my landlord approached me and said, spend two nights with me and I will not charge you for the rent. Make me happy and I will help you. With that, I thought my only [way] out was suicide.” When she refused him, the landlord stole her jewellery and kicked Anju out of her home. Other garment workers report similar stories of harassment and violence from shopkeepers, to whom they have fallen into debt.

Pay a living wage

“The lack of living wages escalated the massive humanitarian crisis brought about by the pandemic,” according to ‘A Stitch in Time’, so it is not surprising that a living wage is the first thing AFWA is calling for.

“Preventing and remediating gender-based violence in homes and factories requires brands to provide living wages for workers and ending all barriers to freedom of association and collective bargaining – especially in women-dominated sectors from the garment industry,” said Saxby.

AFWA also wants to see its ‘Safe Circle Approach’ established across factories. This includes pouring time and resources into building women workers’ leadership on production lines; ending misogynistic power relations between owners and workers; and long-term monitoring and oversight. AFWA says that brands must stop exploiting governance weaknesses and patriarchal social norms in production countries in their quest for profit.

“Vague, superficial and noncommittal promises of brands to eradicate gender-based violence need to be replaced with enforceable, binding commitments to work with women-led trade unions, to develop agreements and programmes to monitor, remediate and prevent GBVH,” Saxby concludes.

* The names of all garment workers have been changed.

No comments:

Post a Comment