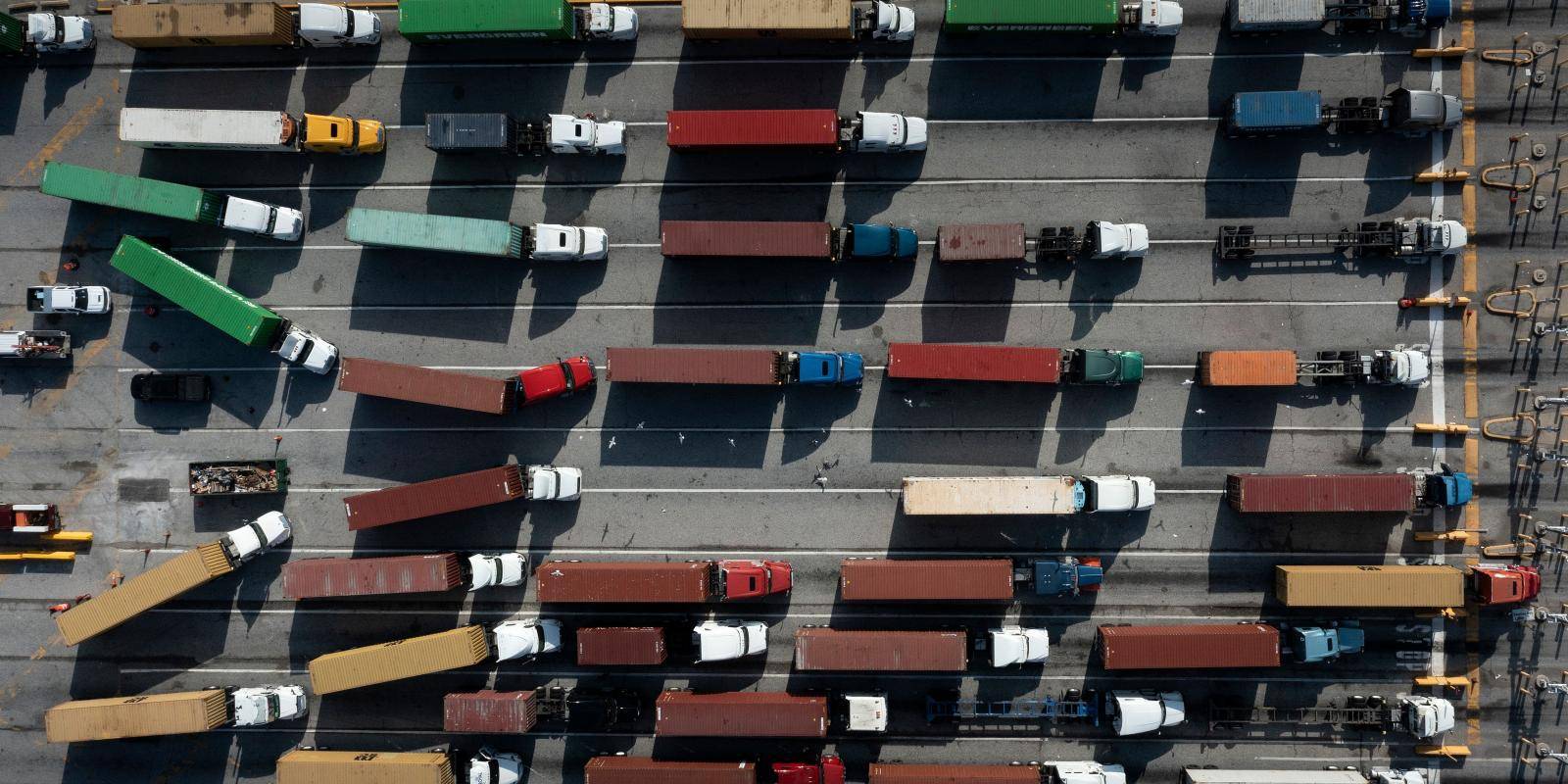

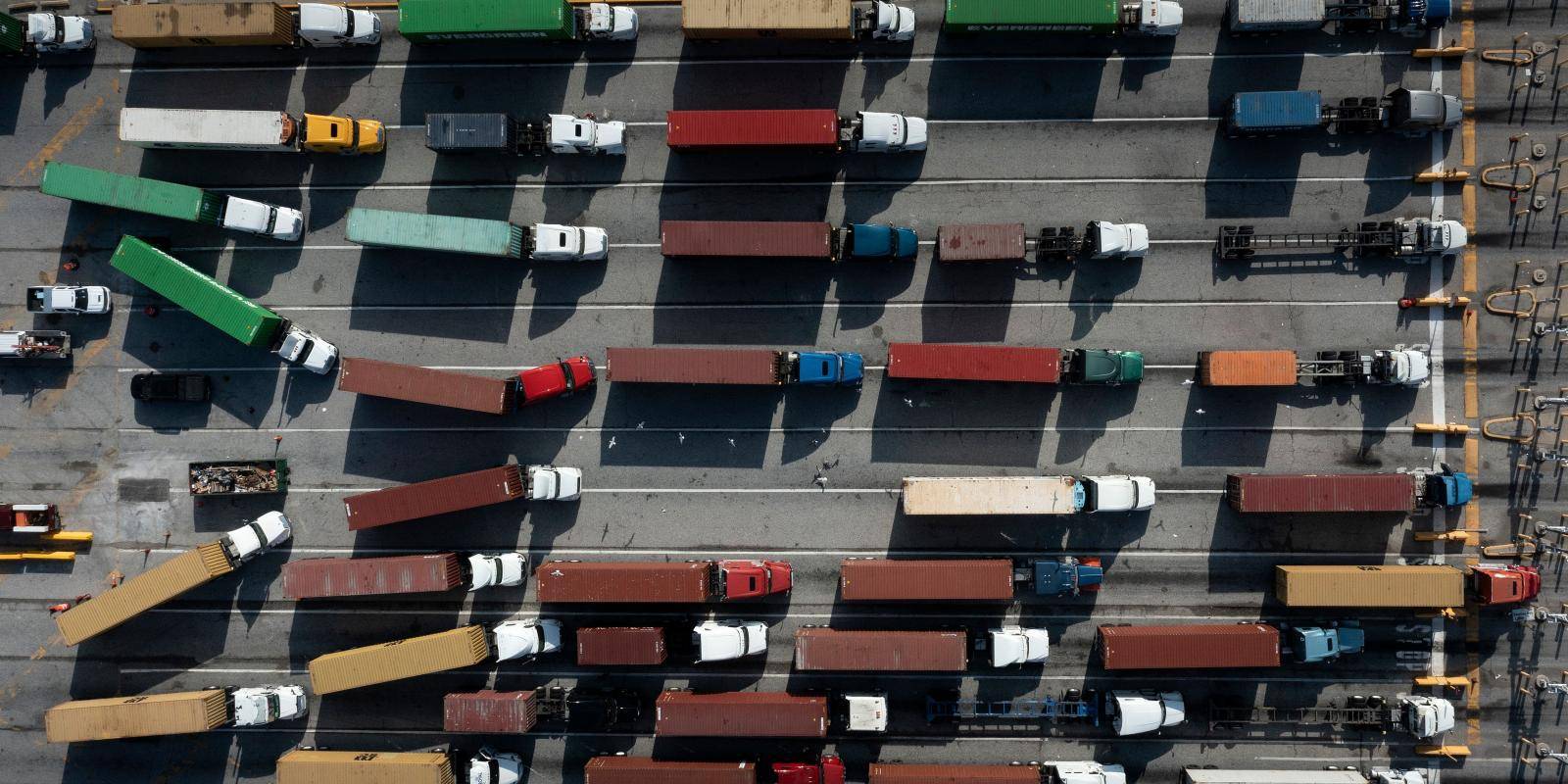

Amongst the tough lessons learnt by companies, nations and alliances from the pandemic has been the fragility of economies and supply chains in absorbing shocks.

EXPERT COMMENT

CHATHMAN HOUSE

![]()

Despite the significant private sector successes in keeping products supplied globally, a reassessment of preparedness has intertwined with the pre-existing sentiment of cautiousness towards external economic threats in the 21st century, heightened by the US-China trade war in 2018 and 2019.

This has led to the increasing appearance of national ‘economic security’ in the lexicon of global administrations, certain to be amplified by the impact of the ongoing war in Ukraine on trade and supply in key energy and agricultural sectors.

In the Asia-Pacific region, Japan’s new prime minister Fumio Kishida has established a dedicated Minister for Economic Security and is in the process of legislating a landmark Economic Security Bill.

Similarly, Australia has set up an Office of Supply Chain Resilience within their government infrastructure and a regional Supply Chain Resilience Initiative partnership with India and Japan to minimize supply chain vulnerabilities that could adversely impact their economic security.

However, this is now a truly global concern. The 2021 UK presidency of the G7 argued ‘for a step-change in global economic governance’ with a renewed focus on the collective management of economic and supply chain risks.

The concept of ‘economic security’ encompasses a broad set of interconnected issues and elements, such as investment screening, anti-coercion instruments research integrity, and supply chain resilience. Focusing on supply chain resilience, there are three fundamental issues to consider.

1. A collective understanding of economic security

Transparency is required between like-minded countries as to their specific definitions of economic security and the strategic policies that underpin it. This will assist in the creation of a clearer framework to facilitate cooperation on the issue where policies overlap.

Transparency is required between like-minded countries as to their specific definitions of economic security and the strategic policies that underpin it.

Difficulty lies in national economic security regimes requiring a balance of defensive and offensive policy design dependent on the specific country condition. Primary factors in building strategies are national security concerns and competitive advantage in certain trade sectors.

Japan, for example, recognizes the tension between the protection of their assets and supply chains against vulnerabilities (through non-disclosure of patents and strengthening of core infrastructure) and simultaneously remaining an active member of a thriving liberalized trading system.

Similarly, the United States has stressed a willingness to work with partners to ‘strengthen and diversify the entire supply chain ecosystem over the long term’ whilst being explicit that self-protection from the threats of China is central to their defensive economic security concerns for supply chain resilience and strengthening trade rules against perceived unfair foreign trade practices.

2. Diplomatic and sustainable diversification of supply chains

Redesigning and diversifying global supply chains to reduce reliance on single sources of production is central to the mitigations that countries are exploring to enhance their economic security.

This process triggers diplomatic tension where nations are trying to ‘wean off’ reliance on geopolitical adversaries in critical sectors. Most notably in reserves of rare earth minerals for semiconductors (vital to the production of numerous high-tech products) dominated by China, which is explicitly mentioned in the strategies of critical and sensitive economic areas from Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom’s Integrated Review.

It is imperative that diversification is undertaken with consideration of sustainability and environmental impacts and whether circular economy principles of recycling and material reuse can be embedded.

Diversification leads to approaches such as the establishment of redundant production capability and stockpiling of products that can protect against future shocks. However, it is worth noting that adapting product supply to multiple sources can make risk management and mitigation more challenging.

Secondly, it is imperative that this is undertaken with consideration of sustainability and environmental impacts and whether circular economy principles of recycling and material reuse can be embedded.

Meaningful private sector engagement by governments is vital to the delivery and continuous improvement of supply chain diversification. It’s necessary for governments at both national and international levels to define their role in regulating public-private partnerships as economies attempt to concurrently protect themselves (e.g. to mitigate against threats such as cyberattacks) and grow (e.g. through the utilization of technological advancement).

3. The role of multilateral institutions

There is consensus amongst global powers that multilateral engagement is beneficial for protection against supply chain vulnerabilities and successful import and export diversification.

Amidst the crowd of international institutions, clarity is required about how they will each play specific and complementary roles in achieving economic security goals, particularly to what extent they can broker agreements between competing powers.

Different preferences have been shown for impactful dialogue from multilateral institutions. As one of their leading members, the United States has unsurprisingly cited the benefits of the G7 forum and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) group with India, Japan and Australia. Whereas the United Kingdom have considered the OECD as an appropriate coordinating organization for developing multilateral approaches to economic resilience.

Transparency and information sharing between nations is the first step in the journey towards meaningful international cooperation on economic security.

Effective trade coordination is paramount in the journey towards economic security. Questions remain as to whether the World Trade Organization is able to sufficiently foster a collaborative environment between members and consequently adapt trade policy.

Amendment to free trade agreements at the bilateral and regional levels may be more effective in sustainably increasing export and import diversification for member countries. The UK’s recent application for membership of CPTPP is considerably driven by the economic security benefits of free trade partnership.

Transparency and information sharing between nations is the first step in the journey towards meaningful international cooperation on economic security. This is critical in avoiding the creation of protectionist economic weapon for nations to deploy against rivals.

Instead, installing economic tools underpinned by legitimate security concerns that both strengthen supply chains and grow competitive trading areas.

21 MARCH 2022

Theo Beal

Richard and Susan Hayden Academy Fellow at the Queen Elizabeth II Academy for Leadership in International Affairs, Asia-Pacific Programme

Theo Beal

Richard and Susan Hayden Academy Fellow at the Queen Elizabeth II Academy for Leadership in International Affairs, Asia-Pacific Programme

Despite the significant private sector successes in keeping products supplied globally, a reassessment of preparedness has intertwined with the pre-existing sentiment of cautiousness towards external economic threats in the 21st century, heightened by the US-China trade war in 2018 and 2019.

This has led to the increasing appearance of national ‘economic security’ in the lexicon of global administrations, certain to be amplified by the impact of the ongoing war in Ukraine on trade and supply in key energy and agricultural sectors.

In the Asia-Pacific region, Japan’s new prime minister Fumio Kishida has established a dedicated Minister for Economic Security and is in the process of legislating a landmark Economic Security Bill.

Similarly, Australia has set up an Office of Supply Chain Resilience within their government infrastructure and a regional Supply Chain Resilience Initiative partnership with India and Japan to minimize supply chain vulnerabilities that could adversely impact their economic security.

However, this is now a truly global concern. The 2021 UK presidency of the G7 argued ‘for a step-change in global economic governance’ with a renewed focus on the collective management of economic and supply chain risks.

The concept of ‘economic security’ encompasses a broad set of interconnected issues and elements, such as investment screening, anti-coercion instruments research integrity, and supply chain resilience. Focusing on supply chain resilience, there are three fundamental issues to consider.

1. A collective understanding of economic security

Transparency is required between like-minded countries as to their specific definitions of economic security and the strategic policies that underpin it. This will assist in the creation of a clearer framework to facilitate cooperation on the issue where policies overlap.

Transparency is required between like-minded countries as to their specific definitions of economic security and the strategic policies that underpin it.

Difficulty lies in national economic security regimes requiring a balance of defensive and offensive policy design dependent on the specific country condition. Primary factors in building strategies are national security concerns and competitive advantage in certain trade sectors.

Japan, for example, recognizes the tension between the protection of their assets and supply chains against vulnerabilities (through non-disclosure of patents and strengthening of core infrastructure) and simultaneously remaining an active member of a thriving liberalized trading system.

Similarly, the United States has stressed a willingness to work with partners to ‘strengthen and diversify the entire supply chain ecosystem over the long term’ whilst being explicit that self-protection from the threats of China is central to their defensive economic security concerns for supply chain resilience and strengthening trade rules against perceived unfair foreign trade practices.

2. Diplomatic and sustainable diversification of supply chains

Redesigning and diversifying global supply chains to reduce reliance on single sources of production is central to the mitigations that countries are exploring to enhance their economic security.

This process triggers diplomatic tension where nations are trying to ‘wean off’ reliance on geopolitical adversaries in critical sectors. Most notably in reserves of rare earth minerals for semiconductors (vital to the production of numerous high-tech products) dominated by China, which is explicitly mentioned in the strategies of critical and sensitive economic areas from Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom’s Integrated Review.

It is imperative that diversification is undertaken with consideration of sustainability and environmental impacts and whether circular economy principles of recycling and material reuse can be embedded.

Diversification leads to approaches such as the establishment of redundant production capability and stockpiling of products that can protect against future shocks. However, it is worth noting that adapting product supply to multiple sources can make risk management and mitigation more challenging.

Secondly, it is imperative that this is undertaken with consideration of sustainability and environmental impacts and whether circular economy principles of recycling and material reuse can be embedded.

Meaningful private sector engagement by governments is vital to the delivery and continuous improvement of supply chain diversification. It’s necessary for governments at both national and international levels to define their role in regulating public-private partnerships as economies attempt to concurrently protect themselves (e.g. to mitigate against threats such as cyberattacks) and grow (e.g. through the utilization of technological advancement).

3. The role of multilateral institutions

There is consensus amongst global powers that multilateral engagement is beneficial for protection against supply chain vulnerabilities and successful import and export diversification.

Amidst the crowd of international institutions, clarity is required about how they will each play specific and complementary roles in achieving economic security goals, particularly to what extent they can broker agreements between competing powers.

Different preferences have been shown for impactful dialogue from multilateral institutions. As one of their leading members, the United States has unsurprisingly cited the benefits of the G7 forum and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) group with India, Japan and Australia. Whereas the United Kingdom have considered the OECD as an appropriate coordinating organization for developing multilateral approaches to economic resilience.

Transparency and information sharing between nations is the first step in the journey towards meaningful international cooperation on economic security.

Effective trade coordination is paramount in the journey towards economic security. Questions remain as to whether the World Trade Organization is able to sufficiently foster a collaborative environment between members and consequently adapt trade policy.

Amendment to free trade agreements at the bilateral and regional levels may be more effective in sustainably increasing export and import diversification for member countries. The UK’s recent application for membership of CPTPP is considerably driven by the economic security benefits of free trade partnership.

Transparency and information sharing between nations is the first step in the journey towards meaningful international cooperation on economic security. This is critical in avoiding the creation of protectionist economic weapon for nations to deploy against rivals.

Instead, installing economic tools underpinned by legitimate security concerns that both strengthen supply chains and grow competitive trading areas.

No comments:

Post a Comment