‘The Brain in Search of Itself’ chronicles the life and work of anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal

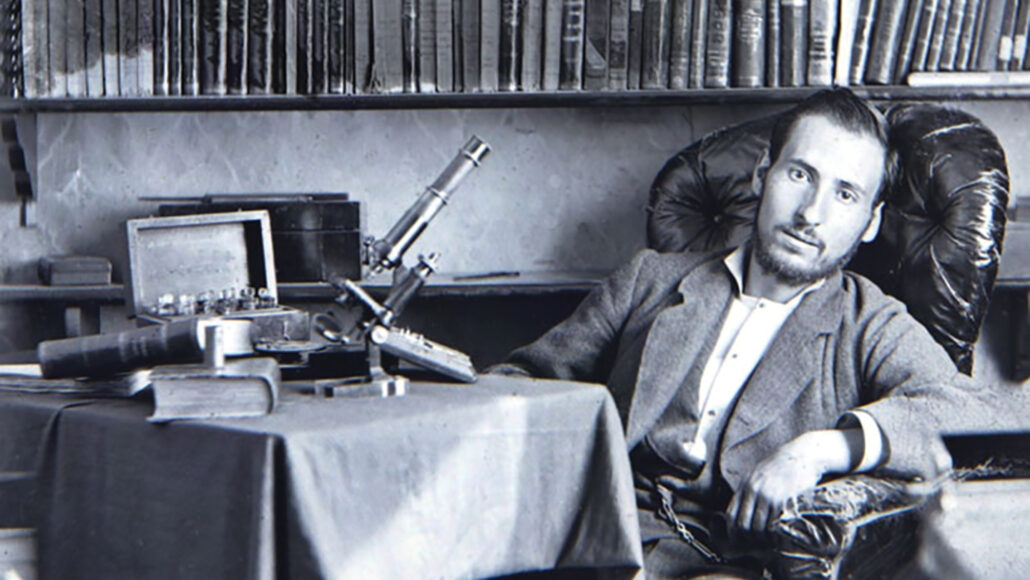

Anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, shown circa 1870, studied brain tissue under the microscope and saw intricate details of the cells that form the nervous system, observations that earned him a Nobel Prize.

S. RAMÓN Y CAJAL/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

By Laura Sanders

MARCH 17, 2022

The Brain in Search of Itself

Benjamin Ehrlich

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35

Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal is known as the father of modern neuroscience. Cajal was the first to see that the brain is built of discrete cells, the “butterflies of the soul,” as he put it, that hold our memories, thoughts and emotions.

With the same unflinching scrutiny that Cajal applied to cells, biographer Benjamin Ehrlich examines Cajal’s life. In The Brain in Search of Itself, Ehrlich sketches Cajal as he moved through his life, capturing moments both mundane and extraordinary.

Some of the portraits show Cajal as a young boy in the mid-19th century. He was born in the mountains of Spain. As a child, he yearned to be an artist despite his disapproving and domineering father. Other portraits show him as a barber-surgeon’s apprentice, a deeply insecure bodybuilder, a writer of romance stories, a photographer and a military physician suffering from malaria in Cuba.

The book is meticulously researched and utterly comprehensive, covering the time before Cajal’s birth to after his death in 1934 at age 82. Ehrlich pulls out significant moments that bring readers inside Cajal’s mind through his own writings in journals and books. These glimpses help situate Cajal’s scientific discoveries within the broader context of his life.

Arriving in a new town as a child, for instance, the young Cajal wore the wrong clothes and spoke the wrong dialect. Embarrassed, the sensitive child began to act out, fighting and bragging and skipping school. Around this time, Cajal developed an insatiable impulse to draw. “He scribbled constantly on every surface he could find — on scraps of paper and school textbooks, on gates, walls and doors — scrounging money to spend on paper and pencils, pausing on his jaunts through the countryside to sit on a hillside and sketch the scenery,” Ehrlich writes.

Cajal was always a deep observer, whether the subject was the stone wall in front of a church, an ant trying to make its way home or dazzlingly complicated brain tissue. He saw details that other people missed. This talent is what ultimately propelled him in the 1880s to his big discovery.

At the time, a prevailing concept of the brain, called the reticular theory, held that the tangle of brain fibers was one unitary whole organ, indivisible. Peering into a microscope at all sorts of nerve cells from all sorts of creatures, Cajal saw over and over again that these cells in fact had space between them, “free endings,” as he put it. “Independent nerve cells were everywhere,” Ehrlich writes. The brain, therefore, was made of many discrete cells, all with their own different shapes and jobs (SN: 11/25/17, p. 32).

Cajal’s observations ultimately gained traction with other scientists and earned him the 1906 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. He shared the prize with Camillo Golgi, the Italian physician who developed a stain that marked cells, called the black reaction. Golgi was a staunch proponent of the reticular theory, putting him at odds with Cajal, who used the black reaction to show discrete cells’ endings. The two men had not met before their trip to Stockholm to attend the awards ceremony.

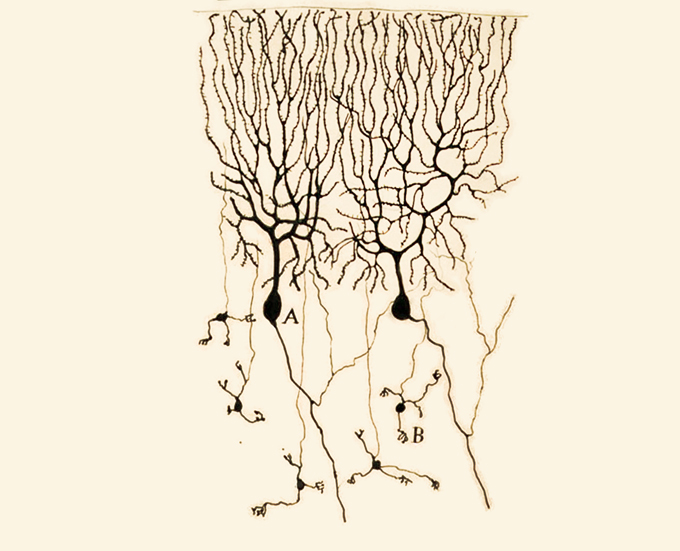

Through his detailed drawings, Santiago Ramón y Cajal revealed a new view of the brain and its cells, such as these two Purkinje cells that Cajal observed in a pigeon’s cerebellum.

SCIENCE HISTORY IMAGES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Cajal and Golgi’s irreconcilable ideas — and their hostility toward each other — came through clearly from speeches they gave after their prizes were awarded. “Whoever believed in the ‘so-called’ independence of nerve cells, [Golgi] sneered, had not observed the evidence closely enough,” Ehrlich writes. The next day, Cajal countered with a precise, forceful rebuttal, detailing his work on “nearly all the organs of the nervous system and on a large number of zoological species.” He added, “I have never [encountered] a single observed fact contrary to these assertions.”

Cajal’s fiercely defended insights came from careful observations, and his intuitive drawings of nerve cells did much to convince others that he was right (SN: 2/27/21, p. 32). But as the book makes clear, Cajal was not a mere automaton who copied exactly the object in front of him. Like any artist, he saw through the extraneous details of his subjects and captured their essence. “He did not copy images — he created them,” Ehrlich writes. Cajal’s insights “bear the unique stamp of his mind and his experience of the world in which he lived.”

This biography draws a vivid picture of that world.

Cajal and Golgi’s irreconcilable ideas — and their hostility toward each other — came through clearly from speeches they gave after their prizes were awarded. “Whoever believed in the ‘so-called’ independence of nerve cells, [Golgi] sneered, had not observed the evidence closely enough,” Ehrlich writes. The next day, Cajal countered with a precise, forceful rebuttal, detailing his work on “nearly all the organs of the nervous system and on a large number of zoological species.” He added, “I have never [encountered] a single observed fact contrary to these assertions.”

Cajal’s fiercely defended insights came from careful observations, and his intuitive drawings of nerve cells did much to convince others that he was right (SN: 2/27/21, p. 32). But as the book makes clear, Cajal was not a mere automaton who copied exactly the object in front of him. Like any artist, he saw through the extraneous details of his subjects and captured their essence. “He did not copy images — he created them,” Ehrlich writes. Cajal’s insights “bear the unique stamp of his mind and his experience of the world in which he lived.”

This biography draws a vivid picture of that world.

No comments:

Post a Comment