By DEEPA BHARATH and COLLEEN SLEVIN

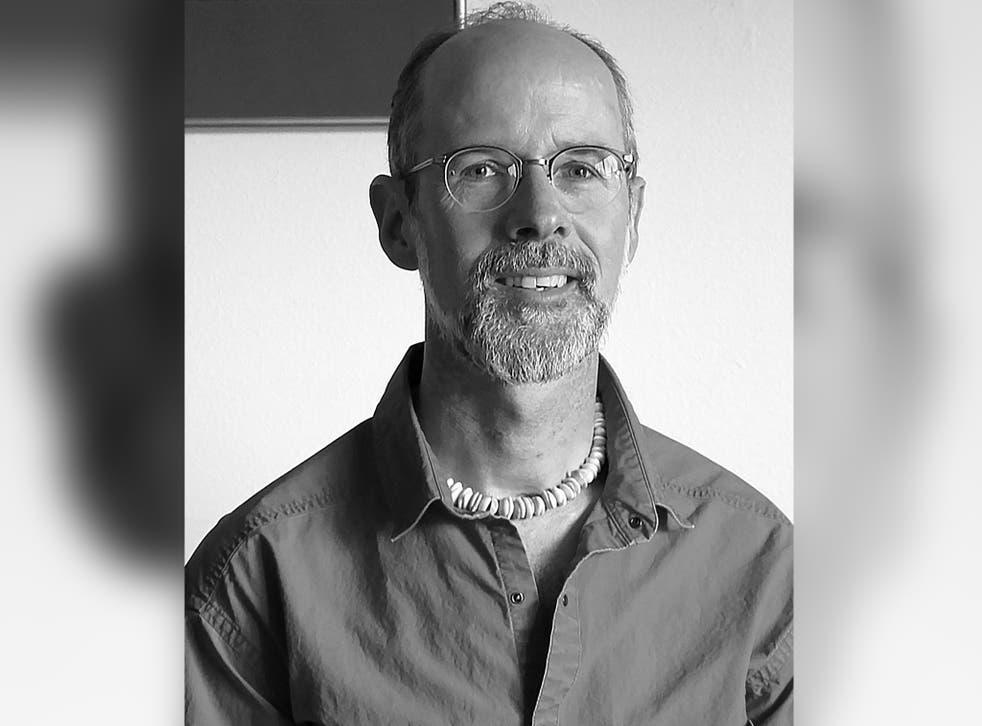

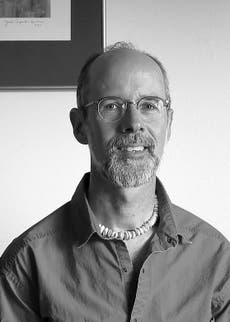

Wynn Bruce, a 50-year-old climate activist and Buddhist, set himself on fire in front of the U.S. Supreme Court last week, prompting a national conversation about his motivation and whether he may have been inspired by Buddhist monks who self-immolated in the past to protest government atrocities.

Bruce, a photographer from Boulder, Colorado, walked up to the plaza of the Supreme Court around 6:30 p.m. Friday – on Earth Day — then sat down and set himself ablaze, a law enforcement official said. Supreme Court police officers responded immediately but were unable to extinguish the blaze in time to save him.

Investigators, who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity, said they did not immediately locate a manifesto or note at the scene and that officials were still working to determine a motive.

On Saturday, Kritee Kanko, a Zen Buddhist priest who described herself as Bruce’s friend, shared an emotional post on her public Twitter account saying his self-immolation was “not suicide” but “a deeply fearless act of compassion to bring attention to climate crisis.”

She added that Bruce had been planning the act for at least a year. She wrote: “#wynnbruce I am so moved.” She got sympathetic responses as well as backlash.

Kanko and other members of the Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center in Boulder, released a statement Monday saying “none of the Buddhist teachers in the Boulder area knew about (Bruce’s) plans to self-immolate on this Earth Day,” and that had they known about his plan, they would have stopped him. Bruce was a frequent visitor to the Buddhist retreat center in the mountains near Boulder where he meditated with the community, Kanko said.

“We have never talked about self-immolation, and we do not think self-immolation is a climate action,” the statement said. “Nevertheless, given the dire state of the planet and worsening climate crisis, we understand why someone might do that.”

On Facebook, Bruce wrote about following the spiritual tradition of Shambhala, which combines Tibetan Buddhism with the principles of living “an uplifted life, fully engaged with the world,” according to the Boulder Shambhala Center. Bruce also posted praise for Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, a leader of engaged Buddhism, around the time of his death in January.

Bruce’s act of sitting down and setting himself on fire was reminiscent of the events of June 11, 1963, when Thich Quang Duc, a Vietnamese monk, seated cross-legged, burned himself to death at a busy Saigon intersection. He was protesting the persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government led by Ngo Dinh Diem, a staunch Catholic. THIS WAS THE EARLIEST ANTI WAR PROTEST AS WELL

In a letter to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr,. whom Hanh counted as a friend, Hanh wrote that he drew inspiration from the Vietnamese monk’s self-sacrifice, saying: “To burn oneself by fire is to prove what one is saying is of the utmost importance. There is nothing more painful than burning oneself. To say something while experiencing this kind of pain is to say it with utmost courage, frankness, determination and sincerity.”

In Tibet, anti-Chinese activists have employed self-immolation as a form of protest. The International Campaign for Tibet says 131 men and 28 women – monks, nuns and laypeople among them – have self-immolated since 2009 to protest against Beijing’s strict controls over the region and their religion.

Buddhism as a religion does not unilaterally condone the act of self-immolation or taking one’s life, said Robert Barnett, a London-based researcher of modern Tibetan history and politics.

“Killing yourself is considered damaging in Buddhism because life is precious,” he said. “But if a person self-immolates because of a higher motivation and it’s not out of a negative emotion such as depression or sadness, then the Buddhist position becomes far more complex.”

If self-immolation is done to help the world, it might be accepted as a positive action, Barnett said. He cited a story from the “Jataka Tales,” a body of South Asian literature concerning the prior incarnations of the Buddha in human and animal form. In that particular tale, an incarnation of the Buddha, in an act of selfless compassion, offers himself to an emaciated tigress who was so hungry that she was ready to devour her own cubs.

“But that kind of self-sacrifice is not encouraged, developed or talked about for normal people (other than the Buddha),” he said, adding that this is because of “the immense difficulty of cultivating positive motivation in any situation, let alone maintaining it under stress or in conditions of extreme pain.”

Buddhism emphasizes emotional balance, inclusiveness, kindness, compassion and wisdom, said Roshi Joan Halifax, an environmental activist and abbot of the Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“What we’re seeing today among many people is hopelessness,” she said. “What we are called to do is not to be disabled by that sense of futility, but to transform our moral suffering into wise hope and courageous action.”

Despite the pessimism that some climate activists may feel, there is reason to remain hopeful, Halifax said.

“You see that people are waking up to the magnitude of the climate catastrophe,” she said, noting that countries and corporations are moving away from damaging practices and toward clean energy.

“I feel inspired and hopeful by our ability to change and adapt in this ever-changing world,” she said. “My heart is heavy that (Bruce) did not have that kind of optimism.”

Those who knew Bruce saw a man who was kind, playful and idealistic – an avid dancer who participated in weekly events. He was also known for biking and embracing public transportation.

Bruce, who enjoyed the outdoors, brought an intensity to whatever he did, said his friend Jeffry Buechler. On Buechler’s wedding day in 2014, Bruce, on a whim, decided to go for a dip in a cold mountain lake early in the morning, he said.

Bruce also suffered lasting effects from a brain injury he sustained in a car wreck that killed his best friend about 30 years ago, Buechler said.

Marco DeGaetano, who met Bruce in the 1990s when they both attended a Universalist church in Denver, said “Wynn seemed to have an affinity for people who needed help.”

He recalled Bruce being kind to a church member with a mental illness when others distanced themselves.

DeGaetano said he last saw Bruce about a month ago, and he seemed outgoing and friendly as always — every time he saw Bruce, “he had a smile on his face.”

___

Bharath reported from Los Angeles and Slevin from Denver. Associated Press writer Michael Balsamo in Washington D.C. and researcher Rhonda Shafner in New York also contributed.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

|

Why it’s so difficult to talk about self-immolation |

Last week, Wynn Bruce, a 50-year-old climate activist, set himself on fire in front of the Supreme Court building. After he died, a woman who identified herself as his friend tweeted that the act was planned to bring attention to the climate crisis. That it happened was reported by national news outlets, but it is difficult to figure out what more to say about self-immolation. |

Bruce’s death reminded me of a time in my life when I was obsessed with finding that something to say. In 2014, I planned a reporting trip to New Delhi to meet with a young Tibetan activist. A few years before, he had tried to self-immolate in protest of Chinese rule of his homeland, but the police tackled him to smother the flames. A 2012 story in The New Yorker estimated that at least 40 Tibetans had self-immolated over the previous year to protest Chinese rule. Total numbers are hard to come by, but needless to say, these acts continue to occur. And the phenomenon is not exclusive to Tibetans. |

I had started thinking about self-immolation in 2013 while reporting on a mass shooting at a nursing school in Oakland, Calif., and how it had ripped apart Tibetan, Korean, Filipino and Nigerian immigrant enclaves in the area. At a coffee shop in Berkeley, I met a Tibetan writer named Topden whom I hoped would give me some insight into his community and help connect me with one of the survivors, a Tibetan nursing student. |

We ended up talking about self-immolation and the nature of death. In my 20s, I had studied Buddhism, and although I had long since wandered off the path to enlightenment for an ego-driven writing career, the idea of detachment was still central to my thinking, as it is today. This was followed by a bout with cancer that shook loose many of my thoughts about dying. In this state, I could understand why someone would sacrifice his or her life to ease the suffering of others. But the act of self-immolation still felt foreign to me — I had never met anyone who believed in anything that much. |

At the time, I was also thinking through the idea of protest and the meaning of sacrifice. In ways that I can now identify as vain and a bit annoying, I did not understand why my friends, many of whom considered themselves “political,” refused to give up anything for their causes. (I, of course, did very little myself.) I was fascinated by how someone arrived at the decision to choose such a painful end. People who set themselves on fire were not, as far as I could tell, activists who were simply choosing a spectacular form of suicide, but rather people who had made a conscious decision to end their lives for what they believed in. |

And yet, the act terrified me as much as it was confusing. And I couldn’t really understand why the Dalai Lama, who seemed to have the influence to stop these self-immolations, appeared almost ambivalent about them. Around the time I was talking to Topden, the Dalai Lama had said that he saw the self-immolations as a form of “nonviolence.” In 2017, he told the TV host John Oliver that he could not condemn them because he did not want the families of the people who had died to feel sorrow that their loved one had gone against the Dalai Lama’s wishes. (This article from the Brown Political Review looks at his stance.) |

I generally try to write in moments of discomfort, but before I was supposed to report the story about the Tibetan activist, there was a larger ethical question that I couldn’t quite resolve. Most people’s knowledge of self-immolation begins and ends with the famous photo of Thich Quang Durc, the South Vietnamese monk who burned himself alive in Saigon in 1963 to protest religious persecution by the government of Ngo Dinh Diem. This image captivated the world and inspired other monks in South Vietnam to follow suit. International media coverage continued, including a dispatch written by a young David Halberstam. Since then, the consensus has been that people self-immolate to shock the public into global outrage over an injustice, or, in Wynn Bruce’s case, an impending catastrophe. This, of course, requires media attention. |

Over a series of conversations with my editor at the time, I realized that by writing a story about self-immolation, I might inspire someone to do it. It didn’t matter that much of the scholarship on Tibetan self-immolation seemed to suggest that international attention wasn’t the only motivating factor. As long as the possibility existed, I did not feel comfortable writing the story, and so I let it go. |

My thoughts about self-immolation receded until 2017, when Aijalon Gomes, a 38-year-old man who had fallen on hard times, was found burned in a park in San Diego. Police weren’t sure whether he had lit himself on fire by accident or had self-immolated. |

Seven years before, when Gomes was teaching English in South Korea, he felt a calling to go teach children in North Korea. Upon crossing into the country through China, he was quickly apprehended and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp. While in custody, he tried to kill himself, but was eventually released after former President Jimmy Carter went to North Korea. Gomes later wrote a book titled “Violence and Humanity: A Saga” about his travails. |

Before any of this, Aijalon Gomes was the resident adviser of my dorm during my freshman year of college. He mostly stayed to himself, but he would quietly tell us please to turn down our music with a reassurance that it wasn’t a big deal. When I talked to my friends from college after hearing about his death, nobody knew what to say other than, “That’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard.” We believed there was no meaning to glean. |

It’s hard to get comfortable with such violence. Wynn Bruce’s act of protest feels senseless because his death will not change the way legislators, corporations and individuals go about their polluting lives. There is a silent calculation among witnesses that accompanies any act of civil disobedience, even those we may agree with on principle: What is the point? This is standard fare for how many people think about protests, violent or not. We tend to pathologize the activists and imagine that they must be animated by the pettiness and greed that motivates us. In many cases, they are. |

But self-immolation forces the witnesses, whether in person or through the news, to confront an intensity of conviction that goes well beyond what they may think is possible. In this way, self-immolators like Thich Quang Durc become almost inhuman, even holy. At the same time, the act establishes an entirely personal connection because the real question at hand isn’t really, “Why did he do that?” Rather, the self-immolator is asking you — with all the intimidation and self-righteousness a person can muster — “Why don’t you care even half as much as I do?” |

I am still horrified by self-immolation, but I also believe that we should resist the urge to write it off as the last act of the mentally ill and the desperate. Nor should we simply frame each incidence with some made-up measure of how much effect it has had on the world. The discomfort we feel over this practice and our sincere desire to see it end should not preclude us from taking it seriously as an act of protest. We should hope this practice ends, but we also shouldn’t just look away. |

Wynn Bruce lit himself on fire on Earth Day 2022 because he believed it might inspire people to work against climate change. There is not any more or less meaning we need to take away from it. |

Wynn Alan Bruce set himself on fire at the Supreme Court. Was his death really a protest about climate?

Some close to the 50-year-old are convinced his death was a protest to coincide with Earth Day, while others said they struggled to understand why he chose to do what he did. Sheila Flynn reports

Last Wednesday, Wynn Alan Bruce asked two neighbours to drive him to the bus station in Boulder, Colorado so that he could travel to Denver.

One was unable to fit the trip into her schedule; the other, his next-door neighbour of 20 years, agreed. Chris King knew that Mr Bruce, 50, had suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a car accident as a teenager so was unable to drive. Instead, Mr Bruce got around the local area on one of his three bicycles – but not a sufficient mode of transport for the nearly 30 mile journey to Denver.

Mr King also knew that his neighbour, who lived alone with his cat in a townhome secured through a city affordable housing programme, had trouble focusing and organising.

Mr Bruce would start projects on his porch and then absent-mindedly abandon them, his neighbour told The Independent. Mr King cleaned up one such pile of collected items this week.

“I dropped him at the bus station, and he had a backpack,” says Mr King. Mr Bruce, who also had a small bag, told his neighbour that he was travelling to Denver to “meet with my meditation group”.

Mr King said: “A couple of days later, the cat was still in the window, and he wasn’t around.

“And then, I found out.”

Mr Bruce died after setting himself on fire on Friday, 22nd April – Earth Day – in front of the US Supreme Court in Washington DC. He was airlifted to hospital by a medical helicopter, and nearby roads were temporarily closed. Mr Bruce died 24 hours later, according to the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD).

His self-immolation was described as “not suicide” the morning after his death, by a woman who described herself as a Zen Buddhist priest and a friend of Mr Bruce.

“This is a deeply fearless act of compassion to bring attention to climate crisis,” Dr K. Kritee, also known as Kritee Kritee or Kritee Kanko, tweeted on Sunday.

The DC police department has given no indication that Mr Bruce left a note, and witnesses said that he was silent before he set himself alight. Police would not comment to The Independent, citing an ongoing investigation.

Police in Boulder, where Mr Bruce lived for more than 20 years, are not involved in any investigations into his death, a spokeswoman told The Independent.

The details of his travels from Colorado to Washington DC are unknown.

While self-immolations have been used in protests before, such as among Buddhists and anti-war protesters during the Vietnam War, this is believed to be only the second time that it has been linked to climate change.

In 2018, climate activist David Buckel, 60, died by self-immolation in Prospect Park in Brooklyn in protest at the use of fossil fuels. Shortly before his death, Mr Buckel emailed a suicide note to several media outlets explaining his actions.

“Most humans on the planet now breathe air made unhealthy by fossil fuels, and many die early deaths as a result — my early death by fossil fuel reflects what we are doing to ourselves,” he wrote. Mr Buckel had been a prominent civil rights lawyer and LGBTQ activist and ran the marriage-equality project at Lambda Legal.

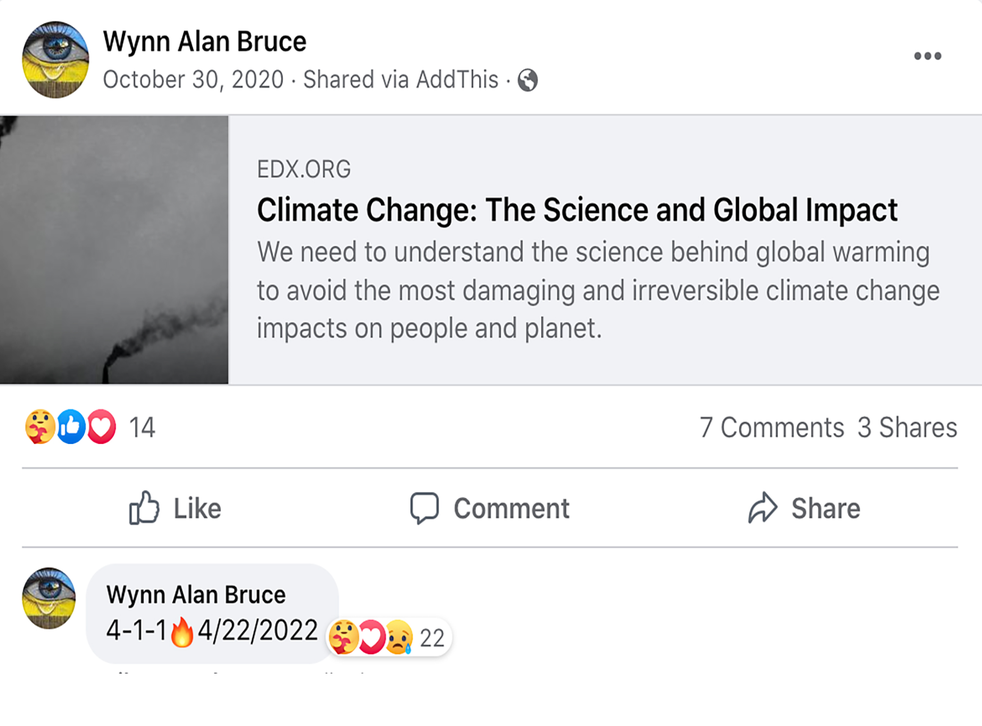

The only public suggestion from Mr Bruce that climate change motivated his actions were a few cryptic Facebook posts. In October 2020, he posted a link about climate change, science and global impact, and last year he commented on that post with a fire emoji and the date 4/22/2022.

Other posts – such as a quote from astronomer Carl Sagan or photos of Walden Pond – suggested a passion for environmental issues and clean air.

Mr Bruce’s father also appeared to suggest that climate change had motivated his son.

“I agree with the belief that this was a fearless act of compassion about his concern for the environment,” Douglas Bruce, 78, told The Washington Post.

“Everybody gets to decide for themselves about how their end of life is going to take place. I honor that. I honor that. I respect him for it.”

Wynn Alan Bruce left a cryptic message on his Facebook page a year before his death

Multiple calls from The Independent to Douglas Bruce were not answered and a message was not returned.

However fellow residents of his quiet complex in Boulder, who’d known him for two decades, expressed extreme shock at his actions.

Several said that they had never heard him mention climate change.

Mr King found out about his neighbour’s death that weekend. The tragic news was shared with him by two people, whom he described as “caretakers”, after they arrived at Mr Bruce’s home.

The visitors told him that Mr Bruce had taken his own life. Another neighbour later discovered online that Mr Bruce had set himself on fire.

“Where did all that come from?” one neighbour had asked, Mr King recalled to The Independent.

“It could be something he was just obsessing about internally,” he added.

Most of Mr Bruce’s Facebook activity focused on Buddhism, meditation, nature and his own photography. He ran a small business called Bright and True Photos taking portraits. At times, he also worked retail jobs.

Mr Bruce loved cycling, hiking and being out in nature, say friends, who universally described him as “sweet”, “gentle”, and “kind.”

At the nearby store Natural Grocers, where Mr Bruce shopped regularly previously worked, employees were “quietly sad”, said a manager who asked not to be named.

“He was in here last week, smiling and happy,” she told The Independent.

She said that his former colleagues were in shock not just at his death but at the “level of planning”.

Pauli Driver-Smith, who tutored Mr Bruce for two years in photography and other subjects, at Front Range Community College described him as “a very kind, caring, compassionate person”.

“He liked talking to people,” she said.

The tutor was paired with Mr Bruce because their interests and talents aligned and, she told The Independent, because she also had a TBI.

Mr Bruce suffered a brain injury in a car crash not long after he graduated from high school in Florida.

According to a St Petersburg Times article, he and a friend were heading to pick up their dates in October 1989, the Washington Post reported, when their Oldsmobile crashed. His friend was killed and Mr Bruce – just days before he was set to join the Air Force – was flown by helicopter to Tampa General Hospital.

He survived with lifelong injuries, derailing his military ambitions and countless other plans that the young and talented athlete had been planning.

It was a “significant accident, and it took him a long time to recover,” his father told The Post.

Ms Driver-Smith told The Independent that she “could relate to [Wynn Bruce’s] struggles”. She said that he could have trouble focusing, calming down, or accurately gauging decisions.

Every TBI differs in effects and severity, according to The Mayo Clinic, with wide-ranging ramifications including everything from inability to organise thoughts and ideas; trouble following and participating in conversations; irritability; lack of awareness of abilities; or issues with multi-tasking, problem-solving or decision-making.

Mr Bruce’s eye for photography was exceptional, Ms Driver-Smith says, and his pictures exuded great “joy,” particularly those focusing on nature.

“I think he felt at peace in nature,” she told The Independent. “Nature has a way of wiping out a lot of the business and everything that’s around you. You get into nature and the quiet and it kind of helps centre you – and that’s one of the things he told me about Buddhism, is that it was helping to center him and helping him to be more grounded.”

Mr Bruce attended retreats at the Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center, about 40 minutes northwest of his house in a pristine mountain landscape, according to neighbours and the Center itself.

The Ecodharma Retreat is not associated with the main Boulder Shambhala Center, in the heart of the city. Boulder Shambhala representatives said that they had no knowledge of Mr Bruce.

Boulder has a large population of Buddhists, with different communities varying in size and beliefs.

Ecodharma’s co-founder, Dr Kritee Kritee, was one of the first people who knew Mr Bruce to make a statement following his death.

In the tweet on Sunday, she wrote: “This guy was my friend. He meditated with our sangha. This act is not suicide. This is a deeply fearless act of compassion to bring attention to climate crisis. We are piecing together info but he had been planning it for atleast one year. #wynnbruce I am so moved.”

A number of people expressed distress on social media at the apparent admiration for Mr Bruce’s violent death.

A day later, Ecodharma released a separate statement which said that the organisation “have never talked about self-immolation, and we do not think self-immolation is a climate action”.

“As we grieve the death of our friend Wynn Bruce and prepare a memorial page to honor him, we want to emphasize that none of the Buddhist teachers in the Boulder area knew about his plans to self-immolate on this Earth Day. If we had known about his plans, we would have stopped him in any way possible. That would be our spiritual, moral and legal responsibility. Just like everyone else, we have been trying to figure out what happened.”

The statement continued: “Nevertheless, given the dire state of the planet and worsening climate crisis, we understand why someone might do that… We hope we can hear Wynn’s message without condoning his method.”

The Independent has tried to reach Dr Kritee and Ecodharma for comment. Dr Kritee referred back to Ecodharma’s written statement.

Friends told The Independent that they struggled to understand how Mr Bruce had planned the trip, and what had convinced him to take his life so publicly and violently.

Beverly Lyne, a nurse who lives across the shared green space from Mr Bruce’s home, told The Independent that he also asked her for a ride last Wednesday. She said her conversations with Mr Bruce had always been casual and light.

“It seems as though he was able to plan and to get the funds to buy a ticket, but I don’t know, I can’t imagine that he put that together,” said Ms Lyne.

“We knew he had issues about just making day-to-day decisions,” she said.

She gestured to the grassy area between their homes.

“Here he’d put his hammock up and then sleep all day. It’s like, Wynn, this is not a campground,” she laughed softly.

Mr King said one neighbour described Mr Bruce as “suggestible”. His former tutor, Ms Driver-Smith, used the same word.

“He was, at times, easily led,” she told The Independent. “He was suggestible, I should say. You could suggest things to him and it was, ‘Oh, that makes sense,’ but I also think that the problem – and this is just a guess on my part, because ... I can be suggestible, and then I sit back and say, ‘Oh, wait a minute, that doesn’t make any sense – but at the moment it did,” she said, adding that it can be hard to “think fast.”

She added: “Getting to Washington DC, I could see him doing it on his own. Once he got to DC, how he managed to find the Supreme Court ... I don’t know, maybe he had help, maybe he didn’t.”

Ms Driver-Smith said that she wanted him to be remembered for his kindness and passion for people.

“He had a lot of potential, and he wanted to make the world a better place.

“I wish… that his passion for environmentalism and his passion for photography, that he had found a way to marry the two into something more positive than setting himself on fire.”

If you are experiencing feelings of distress and isolation, or are struggling to cope, The Samaritans offers support; you can speak to someone for free over the phone, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call National Suicide Prevention Helpline on 1-800-273-TALK (8255). The Helpline is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you.

No comments:

Post a Comment