By Alice Tidey • Updated: 02/04/2022 - 08:31

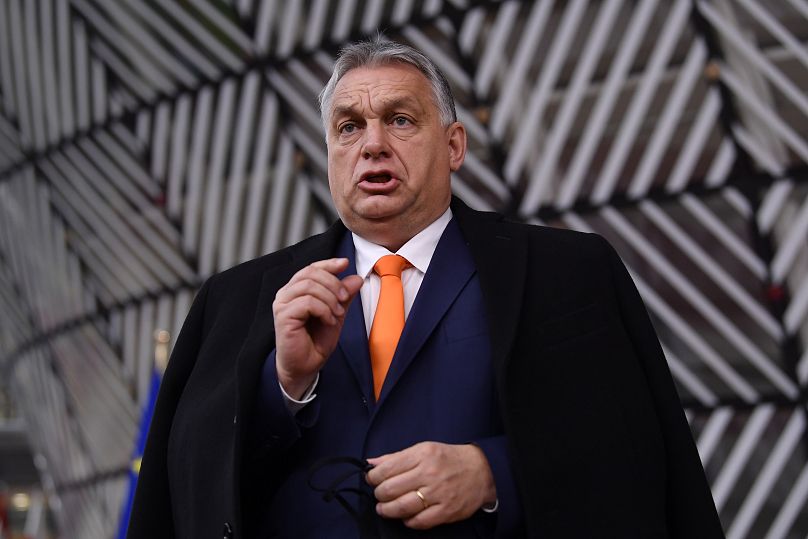

Viktor Orban, Hungary's nationalist Prime Minister delivers his annual state of the nation speech at the Varkert Bazaar conference hall, in Budapest, Hungary, Feb 12, 2022. - Copyright AP Photo/Anna Szilagyi

Viktor Orban, the ultra-conservative Hungarian Prime Minister on the cusp of securing a fifth consecutive term, has built his career on bashing the European Union and has mostly gotten away with it.

Yet, his influence on the bloc and its institutions is chequered at best.

Orban, 58, now the EU's longest-serving leader could on Sunday renew his time at the helm of the eastern country for another four years. His nationalist-populist party, Fidesz, currently has a slight lead over the opposition, which banded together to present a single candidate for the top job and in most constituencies.

His campaign was, as is now usual, filled with attacks against Brussels — its "imperialist tantrums" and "pro-immigrant bureaucrats" — and thin allusions to a possible Huxit.

For years now, Orban has implemented reforms of the judiciary, media and civil society he knew would put him on a collision course with Brussels all while pocketing EU money. Through it all, he cast himself as the protector of traditional — read Christian — European values and promoted an "illiberal democracy" agenda, which once garnered him the moniker "the dictator" by former Commission Chief Jean-Claude Juncker.

Hungary election: A short history of Viktor Orbán's strained relationship with the EU

What this has revealed is that EU institutions are largely unable — or unwilling — to sanction such authoritarian backsliding.

"This anti-Brussels rhetoric is around almost since he took over power and it became more violent after each election," Zsolt Enyedi, a professor and senior researcher at the Central European University's Democracy Institute, told Euronews.

"European Union institutions responded to this barrage of attacks after a while, but they let Orban get away with them for many, many years. Orban was shielded by (former German Chancellor Angela) Merkel and by the European People's Party," he added.

All EU institutions, however, shouldn't be painted with the same brush.

Fidesz isolated in European Parliament

"The European parliament has emerged as a sort of conscience of the EU," Daniel Hegedus, a visiting fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a think tank, said.

MEPs triggered Article 7 proceedings -- calling for the suspension of certain rights -- against Hungary and Poland in September 2018 over rule of law concerns. They have also pushed for the creation of a rule of law mechanism to financially sanction member states seen as backsliding.

Fidesz is now also out of the European People's Party (EPP) group in the parliament, having chosen to leave in March 2021 right before it could get expelled — the party had been suspended from the EPP in 2019. The centre-right EPP was sharply criticised for how long it took them to condemn Orban and Fidesz's domestic policies and to proceed with a possible expulsion course.

"There were different opinions on whether we get them straight inside with internal discussions or should we just kick them out. More or less everybody agreed that the policy line of Fidesz was not right but how to correct this was very much a thing," an EPP insider told Euronews.

"The question before Orban was expelled from the EPP was would Fidesz strengthen the populist side? Would he form a separatist group in the parliament?" the source added.

If that was indeed the plan for Orban, then it backfired.

"The populists are split. They are even more split than they were at the beginning of this term. So there is no such voice as a big united anti-European front," the insider added. "Also as Fidesz is not included in any other group, they are independent, they don't have much to say inside of Parliament, their voice is now practically not heard."

OSCE recommends deployment of election observation mission to Hungary

Parliament now more united

Additionally, the constant attacks on the EU and the reforms it undertook seemed to have boosted MEPs' resolve to protect the bloc as a liberal beacon.

"In my view, the Hungarian Fidesz delegation in the European Parliament, and Fidesz when it was in the EPP, strengthened the topics of rule of law, democracy, human rights and women's rights in the EP as a whole and also in the EPP group. This was precisely because Fidesz challenged all of these values so strongly," Sirpa Pietikainen, a Finnish EPP MEP, told Euronews.

"Without the challenging from Fidesz of these values, it could even be that we would now have a less defined and less united position on rule of law, human rights violations or gender equality issues. Sometimes the paradox is that by challenging something you end up strengthening the principle you challenge. A bit like Putin's actions in Ukraine right now," she argued.

But while MEPs have triggered Article 7 and have now pushed for the use of the new rule of law mechanism against Hungary, nothing much has happened. Action is out of their hands.

Commission 'failed tests'

The Commission, which acts as the guardian of the treaties and defender of EU legislation, has launched and won multiple court cases against Budapest over changes in the Hungarian Constitution, the lowering of the retirement age for judges, the crackdown on NGOs and the treatment of migrants and refugees.

Yet, not much has changed.

"This was far too little, so it didn't make much difference on the ground. These court decisions almost always go against Hungary and some of the other violators of fundamental norms of liberal democracy but they are not respected, and the Commission doesn't do much about that," Enyedi said.

For Hegedus, "the Commission failed these tests" launched by the parliament and court decisions, and with "the rule of law issue practically off the table" due to the Russian aggression on Ukraine, Orban knows he "doesn't need to fear the Commission or sanctions".

Council's need for compromise

The European Council, i.e. leaders of member states, have been equally weak in their ability to rein in Orban and Fidesz, the two experts said.

"The EU has many other challenges and you do need the support of Hungary's prime minister for tackling these challenges, so they have to make various compromises. The rule of law mechanism keeps being postponed and it has been watered down anyway and only applies to some very, very specific violations of rule of law and not a general drift towards authoritarian rule," Enyedi explained.

Yet even though the Council — especially Poland which has similarly drawn the ire of Brussels — largely protects Orban from MEPs' wrath, leaders are still not fooled.

Orban's veiled references to a Huxit are not seen as credible by his fellow heads of state who are still reeling from the consequences of the UK's departure from the union.

"The whole operation of the Orban regime -- which is built on the strategic corruption and abuse of EU funds --, this political system is not operational outside of the European Union," Hegedus explained.

"The Hungarian government did a lot on its multilateral foreign policy and close ties with Russia and China to demonstrate for the EU institutions that it has other strategic options but these strategic options are not genuine. Neither Russia, nor China, would be ready to provide that sort of financial transfer for Hungary which amounts to 3-4% of its annual GDP. So no, I think leaving the European Union is not an option," he added.

'Enlargement fatigue'

Orban's shift toward a semi-authoritarian regime may have also impacted the bloc's enlargement — unchanged since the accession of Croatia in 2013. The Hungarian leader has been developing closer ties with leaders in the Western Balkans, where many countries hope one day to become member states, but where democratic and rule of law standards are spotty.

"I think the democratic demise in Central Europe, and especially in Hungary and Poland, significantly contributed to enlargement fatigue in some member states," Hegedus said.

For Enyedi, "Hungary is an example of how accession of a new country can go wrong."

"The very strong ties between (Serbian President Aleksandar) Vučić and Orban mean that if Serbia was accepted, you know, the Orban bloc will get stronger and nobody wants that. So in that sense, I think Serbia's accession prospects are directly hurt by this strong cooperation between the leaders of the two countries," he added.

As for Orban's hope of exporting its "illiberal democracy" model to other member states, this too has largely stalled, mostly because, as is the case in the European Parliament, right-wing populist parties across the bloc do not actually align on many issues.

Even the Visegroup group, comprising the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary, has many cracks and these are widening because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine with Warsaw resolutely anti-Russia while Orban has been much more conciliatory.

"He put a lot of energy into supporting forces that could undermine liberal democracy in Europe," Enyedi stressed, including "directly interfering with domestic politics" in non-EU neighbouring countries or in fellow member states — a Hungarian bank with close ties to him provided a €10.7 million loan to French far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen to fund her campaign.

"He has been trying to build an authoritarian right-wing alliance for a long time, which was not successful, and actually now, the prospects are not very good," he concluded.

Hungary election: Who is Viktor Orban and how has he stayed in power for so long?

By David Hutt • Updated: 30/03/2022

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban gestures after delivering his annual state of the nation speech, 12 February, 2022. Slogan reads "Let's go forwards, not backwards!" - Copyright Credit: Reuters

To his supporters, Hungary's prime minister Viktor Orban represents true European values: Christianity; the predominance of the nation-state; government for the masses, not the elites.

To his critics, he’s an opportunistic populist who cares only about his own power and has made Hungary a pariah within Europe.

In this Sunday's (3 April) election, Orban, who's been in office since 2010, faces his biggest challenge yet to stay in power.

Who is Viktor Orban and how did he come to power?

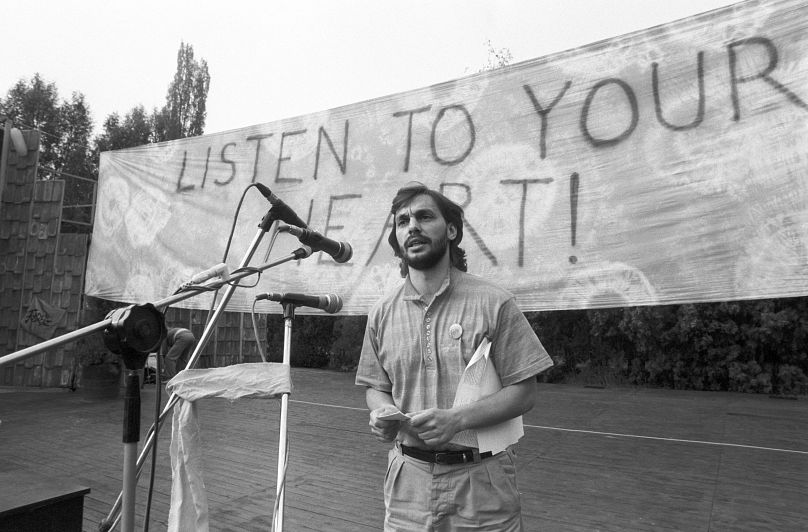

In March 1988, Orban was anything but a right-wing autocrat. He and his fellow students at Bibo College near Budapest — many of whom would be rewarded with top jobs in his governments — formed the Alliance of Young Democrats, or Fidesz, an ostensibly liberal-orientated movement.

His first taste of fame came the following year when he gave a rousing speech in Heroes’ Square in Budapest, just as the country’s communist regime was collapsing.

At Hungary’s first free election, in April 1990, Orbán’s youthful party won 22 out of 386 seats in parliament.

Analysts tend to divide Orbán’s political metamorphosis across three stages.

Since the early 1990s, “he transformed from a liberal politician first to a national-conservative, and later to a populist radical-right leader,” said Daniel Hegedüs, an analyst at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

A younger Viktor Orban at a Fidesz party congress in 1990. 'Listen To Your Heart' was their campaign song and slogan.Credit: Földi Imre/MTVA

On the one hand, this could be put down to sensible politics. Centre-right parties led the Hungarian government between 1990 and 1994, so it made sense for Fidesz, in opposition, to take up left-wing causes.

But the leftist government of Prime Minister Gyula Horn, from 1994 until 1998, was marked by calamity. With the economy failing, Horn was forced to impose crippling privatisation and austerity policies in return for financial support from abroad.

Now, it made sense for Orbán to attack the ruling party from the right. In a party speech in April 1995, he declared that Fidesz “must seek cooperation with the forces politically right of centre.”

That year, the party was renamed Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Party.

But analysts say more dangerous motives lurk behind Orbán’s protean nature. First, shifting between political positions allowed him to build up his own personal power. Around 1993, Orbán, who was vice-president of Fidesz at the time, pressured the party to move rightwards. As a result, liberal-minded members, including the more popular Gábor Fodor, left to join another party. Orbán was elected Fidesz chairman thereafter, cementing himself as its indisputable figure.

The Hungarian-born journalist Paul Lendvai, in his 2017 biography Orbán: Hungary's Strongman, identifies another personality trait that explains his career: a deep-seated sense of inferiority.

Born in 1963 near the city of Székesfehérvár, Orbán’s family was rural middle-class. A bright student — he studied at the University of Oxford for a year on a scholarship — he nonetheless perceived himself as being treated by others as a provincial. He felt patronised by leftist intellectuals in the early 1990s. His sense of inferiority, Lendvai wrote, made him particularly susceptible to feelings of “betrayal” by allies, and to the “cosmopolitan Europhiles” who dominated many of the other political parties.

In May 1998, to the surprise of many, Fidesz won the most seats in parliament at the country's general election, with Orbán becoming the youngest head of government in Europe at the time.

He entered government through a coalition with the centre-right Independent Smallholders Party and Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF).

“His first government period between 1998 and 2002 happened in his national-conservative period, and his politics were largely in compliance with liberal democratic principles,” said Hegedüs.

Much of that changed after the next election in 2002. Although the Fidesz-MDF alliance won the most seats, a left-liberal alliance was able to form a coalition government, evicting Orbán from office. He cried foul of electoral fraud and poor treatment by left-leaning newspapers. In opposition, Fidesz drifted further towards the political right. His nationalism was ratcheted up. He began to rail against the Treaty of Trianon, a post-First World War agreement that stripped Hungary of around two-thirds of its territory and two-fifths of ethnic Hungarians, who found themselves living in newly independent, neighbouring countries.

In a now-infamous speech in 2009, delivered at a closed-door party meeting, he called for a “central political forcefield” that would govern the country for the next decades. After almost a decade in opposition, by 2010 Orbán had been able to craft “a coherent national ideology attractive for a large part of the Hungarian society”, said Hegedüs.

On the one hand, this could be put down to sensible politics. Centre-right parties led the Hungarian government between 1990 and 1994, so it made sense for Fidesz, in opposition, to take up left-wing causes.

But the leftist government of Prime Minister Gyula Horn, from 1994 until 1998, was marked by calamity. With the economy failing, Horn was forced to impose crippling privatisation and austerity policies in return for financial support from abroad.

Now, it made sense for Orbán to attack the ruling party from the right. In a party speech in April 1995, he declared that Fidesz “must seek cooperation with the forces politically right of centre.”

That year, the party was renamed Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Party.

But analysts say more dangerous motives lurk behind Orbán’s protean nature. First, shifting between political positions allowed him to build up his own personal power. Around 1993, Orbán, who was vice-president of Fidesz at the time, pressured the party to move rightwards. As a result, liberal-minded members, including the more popular Gábor Fodor, left to join another party. Orbán was elected Fidesz chairman thereafter, cementing himself as its indisputable figure.

The Hungarian-born journalist Paul Lendvai, in his 2017 biography Orbán: Hungary's Strongman, identifies another personality trait that explains his career: a deep-seated sense of inferiority.

Born in 1963 near the city of Székesfehérvár, Orbán’s family was rural middle-class. A bright student — he studied at the University of Oxford for a year on a scholarship — he nonetheless perceived himself as being treated by others as a provincial. He felt patronised by leftist intellectuals in the early 1990s. His sense of inferiority, Lendvai wrote, made him particularly susceptible to feelings of “betrayal” by allies, and to the “cosmopolitan Europhiles” who dominated many of the other political parties.

In May 1998, to the surprise of many, Fidesz won the most seats in parliament at the country's general election, with Orbán becoming the youngest head of government in Europe at the time.

He entered government through a coalition with the centre-right Independent Smallholders Party and Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF).

“His first government period between 1998 and 2002 happened in his national-conservative period, and his politics were largely in compliance with liberal democratic principles,” said Hegedüs.

Much of that changed after the next election in 2002. Although the Fidesz-MDF alliance won the most seats, a left-liberal alliance was able to form a coalition government, evicting Orbán from office. He cried foul of electoral fraud and poor treatment by left-leaning newspapers. In opposition, Fidesz drifted further towards the political right. His nationalism was ratcheted up. He began to rail against the Treaty of Trianon, a post-First World War agreement that stripped Hungary of around two-thirds of its territory and two-fifths of ethnic Hungarians, who found themselves living in newly independent, neighbouring countries.

In a now-infamous speech in 2009, delivered at a closed-door party meeting, he called for a “central political forcefield” that would govern the country for the next decades. After almost a decade in opposition, by 2010 Orbán had been able to craft “a coherent national ideology attractive for a large part of the Hungarian society”, said Hegedüs.

Viktor Orbán with his daughter Ráchel at the Fidesz national campaign launch event in 1994

Viktor Orbán with his daughter Ráchel at the Fidesz national campaign launch event in 1994Credit: Illyés Tibor/Magyar Távirati Iroda Zrt

How has Viktor Orban managed to stay in power for so long?

Fidesz's overwhelming victory in the 2010 general election freed Orbán’s hand, analysts say, allowing him to rework the constitution in 2012.

In alliance with the Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP), its small satellite party, Fidesz went on to win a two-thirds majority in parliament in 2014 and 2018.

During this period independent media were shut down, while friendly newspapers were lavished. Courts were packed with cronies. The electoral system was re-written. Nationalism was ramped up, especially amid the 2015 migrant crisis in Europe, when Orbán’s government erected fences to keep out the mainly Muslim refugees. Internationally, Orbán made friends with the authoritarian governments of Russia and China, whose interests he has protected during EU voting. Meanwhile, Brussels challenged Hungary to mend its ways, now threatening to restrict economic relief until political reforms are made.

Andras Bozoki, professor of political science at the Central European University in Vienna, reckons Orbán’s autocratic tendencies were present from the outset of his career, and he had transformed Fidesz into a “highly centralised party” by 2003. However, this was masked during his first spell as prime minister, between 1998 and 2002, since Orbán had to govern as part of a coalition with two relatively strong parties.

What has kept Orbán in power? For Bozoki, it’s largest due to the political and constitutional changes enforced since 2010, which have clothed Orbán in immense power. Some changes are subtle. In 2014, for instance, the share of MPs elected from single-member constituencies — which favours Fidesz — was raised to 106 out of the 199 seats in parliament. The rest are appointed by proportional representation. At the 2018 ballot, Fidesz won just 49% of the popular vote but picked up 67% of seats in parliament.

Many of Fidesz’s populist policies are, indeed, popular, analysts say. The state invests heavily in welfare spending.

“He is a charismatic populist politician who used heavy state propaganda and always found an enemy to fight with,” Bozoki said.

Any problem in the country is usually blamed on Orbán’s go-to villains: migrants, the EU, or George Soros, a Hungarian-born philanthropist who Orbán claims is trying to impose cosmopolitan liberalism onto Hungary from afar.

Orbán has also been fortunate. He took power in 2010 as European economies were beginning to recover from the global financial crisis. Hungary’s economy contracted by 6.7% in 2009 but began to grow at a steady rate afterwards. In 2018, it grew by 5.4%, the largest annual increase of the post-communist era. At the same time, Orbán was fortunate in having to face off against a divided opposition. At the 2018 general election, almost 80 parties competed, with six gaining more than 1% of the vote.

Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban speaks as he arrives for an EU summit at the European Council building in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 10, 2020

Credit: John Thys/AP

Orbán’s facing his toughest fight yet

Come 3 April, Orbán faces a far different threat.

In December 2020, six of the country’s largest opposition parties, as well as some smaller groups and movements, agreed to contest the 2022 election as part of the United for Hungary alliance. After extensive primaries, the non-partisan Péter Márki-Zay, the mayor of the southeastern city of Hódmezővásárhely, was selected as the alliance’s prime ministerial candidate.

The latest opinion polls, taken in late March, vary greatly. Republikon, a think-tank, gives Fidesz a three percentage point lead on the opposition alliance. According to Társadalomkutató, another pollster, it has an eleven point advantage. Most pundits expect another victory for Fidesz and its junior KDNP partner, but they are not overly sure.

Much lies in its favour. It has much more money: perhaps around 20 times more than the opposition alliance, reckons Bozoki, of the Central European University. And Fidesz can use the electoral law to their own advantage.

“Since Hungary is not a democracy, but a competitive authoritarian regime, and there will be no free and fair elections, Fidesz always has a high chance to win,” Bozoki added.

Despite this, the opposition alliance cannot be ruled out. Analysts point to a large share of undecided voters in the opinion polls, suggesting that the outcome could be close.

Márki-Zay, the opposition candidate, is something of a conservative, which might attract some Fidesz supporters and undecided voters.

Liberals will opt for the opposition alliance regardless.

Dániel Mikecz, an analyst with the Republikon think-tank, reckons that even if Fidesz wins, it is likely to lose its supermajority in parliament. That could stymie its ability to alter political institutions and could make it more vulnerable to opposition attacks in parliament, but probably won't have any effect on Orbán’s style of leadership, said Mikecz. Fidesz would likely continue with their “polarising way of making politics.”

For some analysts, an opposition victory would fundamentally change Hungary. A new administration would drop many of Orbán’s most controversial policies and loosen up the political system. It would make peace with the EU. Without state funds, Fidesz would struggle to keep its loyal media and affiliates on side.

But the United For Hungary alliance is precarious. Its composite parties rarely see eye to eye on the most important issues. Agreements over which candidates to field have been unsteady. It is also lop-sided: most of its support comes from two parties, the liberal Democratic Coalition (DK) and the right-wing Jobbik, according to the latest opinion polls. How it would actually go about forming a coalition government is another matter, perhaps one best left for late-night arguments if the opposition alliance secures a surprise victory next Sunday.

Orbán’s facing his toughest fight yet

Come 3 April, Orbán faces a far different threat.

In December 2020, six of the country’s largest opposition parties, as well as some smaller groups and movements, agreed to contest the 2022 election as part of the United for Hungary alliance. After extensive primaries, the non-partisan Péter Márki-Zay, the mayor of the southeastern city of Hódmezővásárhely, was selected as the alliance’s prime ministerial candidate.

The latest opinion polls, taken in late March, vary greatly. Republikon, a think-tank, gives Fidesz a three percentage point lead on the opposition alliance. According to Társadalomkutató, another pollster, it has an eleven point advantage. Most pundits expect another victory for Fidesz and its junior KDNP partner, but they are not overly sure.

Much lies in its favour. It has much more money: perhaps around 20 times more than the opposition alliance, reckons Bozoki, of the Central European University. And Fidesz can use the electoral law to their own advantage.

“Since Hungary is not a democracy, but a competitive authoritarian regime, and there will be no free and fair elections, Fidesz always has a high chance to win,” Bozoki added.

Despite this, the opposition alliance cannot be ruled out. Analysts point to a large share of undecided voters in the opinion polls, suggesting that the outcome could be close.

Márki-Zay, the opposition candidate, is something of a conservative, which might attract some Fidesz supporters and undecided voters.

Liberals will opt for the opposition alliance regardless.

Dániel Mikecz, an analyst with the Republikon think-tank, reckons that even if Fidesz wins, it is likely to lose its supermajority in parliament. That could stymie its ability to alter political institutions and could make it more vulnerable to opposition attacks in parliament, but probably won't have any effect on Orbán’s style of leadership, said Mikecz. Fidesz would likely continue with their “polarising way of making politics.”

For some analysts, an opposition victory would fundamentally change Hungary. A new administration would drop many of Orbán’s most controversial policies and loosen up the political system. It would make peace with the EU. Without state funds, Fidesz would struggle to keep its loyal media and affiliates on side.

But the United For Hungary alliance is precarious. Its composite parties rarely see eye to eye on the most important issues. Agreements over which candidates to field have been unsteady. It is also lop-sided: most of its support comes from two parties, the liberal Democratic Coalition (DK) and the right-wing Jobbik, according to the latest opinion polls. How it would actually go about forming a coalition government is another matter, perhaps one best left for late-night arguments if the opposition alliance secures a surprise victory next Sunday.

No comments:

Post a Comment